The physician has a Hobson's choice in deciding if an older driver with problems of normal aging, disease, and medications should continue to drive. Several cases are presented here to illustrate the problem, open dialogue, and present a partial solution.

The ability to drive will prevent or delay the onset of maladaptive correlates of aging, namely the loss of independence. In the year 2000, 18.9 million older drivers were licensed, which is an increase of 36% since 1990 (CitationUS Department of Transportation 2001). Moreover, there was a 12% increase of the over-65 population within this same time period. It is unknown how many older people lose their licenses due to poor health or are turned in by their physicians for medical reasons, as stipulated by law due to Federal Privacy Laws. Furthermore, information about how many older persons voluntarily give up their licenses is also not known. In view of the increasing number of elderly drivers, one of the largest automobile insurance companies in the US has produced an attractive booklet for discussing “family conversations” with older drivers. This highlights the problem that individuals and families, in most cases, do not stop impaired older drivers from driving. The medical profession needs an outside agency to insulate them from a difficult decision and still fulfill their responsibility to society.

Normal aging has a major influence on vision, hearing, reaction time, and mobility. Furthermore, there are a number of common diseases that impact the older driver such as atherosclerosis and all its consequences, hypertension, degenerative joint disease, and diabetes. The geriatric population also takes many drugs, both prescription and over-the-counter, and these have side effects that can influence the ability of the older driver to manage an automobile (CitationFinestone 2003).

The reality of aging is that many of the physical and mental skills needed to safely operate a motor vehicle deteriorate. Older drivers have diminished vision, particularly at nighttime, reduced depth perception, greater sensitivity to glaring lights, reduced muscle strength, decreased flexibility of neck and trunk, slower reaction time, and less ability to divide their attention among various tasks, therefore decreasing their ability to make quick judgments.

In light of the July 2003 accident in Santa Monica, CA, USA, where an elderly male driver sped down the length of an outdoor market killing 10 out of 50 persons struck by his car, the topic of driving in the elderly has become front-page news.

The fatality rate for drivers 85 years and older is nine times that of drivers in the aged 25–69 according to the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (CitationUS Department of Transportation 2001). Motor vehicle crashes are the leading cause of injury-related deaths for people aged 65–70, again emphasizing the seriousness of this problem (CitationTraffic Safety Facts 2002). The burden of deciding which older person should drive or not drive places a physician in a very difficult situation. Many older drivers almost totally depend on their cars for transportation for medical visits, shopping, religious services, and socialization. Driving affords them a certain amount of independence and is very important for maintaining quality of life. National Patient Privacy laws further add to the complexity of the problem.

The following case reports originate from the author's geriatric practice and illustrate some of the problems practicing physicians face. One proposed solution is the use of driving schools, which exist in some states of the US. Such schools may involve a medical referral and allow third-party evaluation of an older person's driving ability and degree of safety (see Appendices 1 and 2). However, there is a cost involved, which could be subsidized by the state or federal government rather than putting the burden on the older driver.

Case 1

LL is an 84-year-old retired lawyer with coronary artery heart disease, post-coronary artery bypass, and has had a recent stroke. At his last examination he had mild dementia, a wide-based gait and difficulty walking, and some expressive aphasia. At this visit, I told the patient that I did not believe it was safe for him to drive, inasmuch as his wife would be able to accommodate him as far as his transportation needs were concerned. He became very upset and refused to consider it. I called his wife and suggested that she remove his keys. She also was reluctant to accept it, but finally did. His daughter, who is a lawyer, did not accept this. I told her the same story and finally reported him to the Department of Transportation as being unfit to drive. I never heard from them again or from the Department of Transportation.

Case 2

MG is an 80-year-old man with type II diabetes, coronary artery disease, and he has had a stroke some years ago after internal carotid artery surgery. He did not have dementia but had some difficulty in his gait due to a mild left hemiparesis. Both he and his wife had lived in the same two-story house for 50 years and finally, after my recommendation, moved to an apartment. The move to the apartment was associated with a severe depression in both that did resolve. The patient's wife, who was also my patient, did not drive and had increasing problems with Alzheimer disease. At the last visit, I told MG that I didn't think it was safe for him to drive. He became very frustrated, since his wife did not drive and this would create a problem with shopping. He had an only son who was very supportive, but lived in California. I called the son and explained the situation to him. He immediately came back to Philadelphia and had his parents moved to an assisted living facility, where transportation and medical care is provided.

Case 3

MW, an 85-year-old male with known coronary artery disease, severe osteoarthritis, and taking multiple medications, agreed to be evaluated by the driving school. He was also able to pay the fee. MW passed his driver evaluation, but it was recommended that he drive only in local areas during daytime hours. The school also stated that if he did not follow through with these restrictions, he could be reported to the New Jersey Department of Motor Vehicle Medical Unit. Also, it was recommended that he return annually for a repeat evaluation, or sooner if I had any concerns.

Case 4

RA is an 87-year-old male with marked difficulty in walking due to some degenerative joint disease involving neck and spine. He agreed to be evaluated by the driving school and was able to afford the fee. The patient passed the evaluation and was ready to return to driving with an evaluation in 12 months or sooner if indicated.

Discussion

A study from the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine concluded that to stop a patient from driving is not easy, but that taking no action may result in deadly consequences (CitationMessinger-Rappoport 2002). Concerning the problem of the older driver, local governments are now debating whether to subject older drivers to special tests, but they have two obstacles: one is political and the other is financial. However, the Maryland Pilot Older Driver Study has indicated that a battery of tests could cost as little as US$5.00 to administer (CitationUS Department of Transportation 2003). The authors of this study indicate that the estimated US$200 000 cost for screening all drivers over the age of 75 would be a wise move since the cost of a single traffic fatality or critical injury is close to US$1 000 000. According to a program by the Road Information Program called Designing Roadways to Safely Accommodate the Increasingly Mobile Older Driver, from 1991 to 2001, the number of Americans aged 70 or older, who died in traffic accidents, grew by 27%.

In anticipation of a longer healthier lifespan, many older Americans postpone retirement and continue to live independent lives, and transportation is essential to their independence. Surveys have indicated that the motor transportation preferred by most Americans is automobile as either drivers or passengers.

In planning transportation options in services to meet the mobility needs of the elderly, it is important to recognize the value placed upon transportation. Transportation enables older persons to maintain social support systems needed for good quality of life and it reduces the risk of premature morbidity and mortality by decreasing isolation and depression. It should also be recognized that personal control in deciding where and when to go is important to older people. It is clear that there is a growing need for more desirable options that provide mobility for older people while allowing them to retain as much independence as possible.

References

- FinestoneAJTo drive or not to drive? That is the questionAnn Long Term Care200311469

- Messinger-RappoportBJHow to access and counsel the older driverCleve Clin J Med2002691845 189–90, 19211890209

- Traffic Safety Facts2002 Older population [online]. US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Accessed 17 Jan 2003. URL: http://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/pubs/7.pdf

- US Department of TransportationTraffic safety facts 2001: older population2001WashingtonNational Highway Traffic Safety Administration CDOT HS 809,475

- US Department of Transportation, National Highway Safety AdministrationModel Driver Screening and Evaluation Program. Volume 2. Maryland Pilot Older Driver Study2003 Springfield National Technical Information Service

Appendix 1

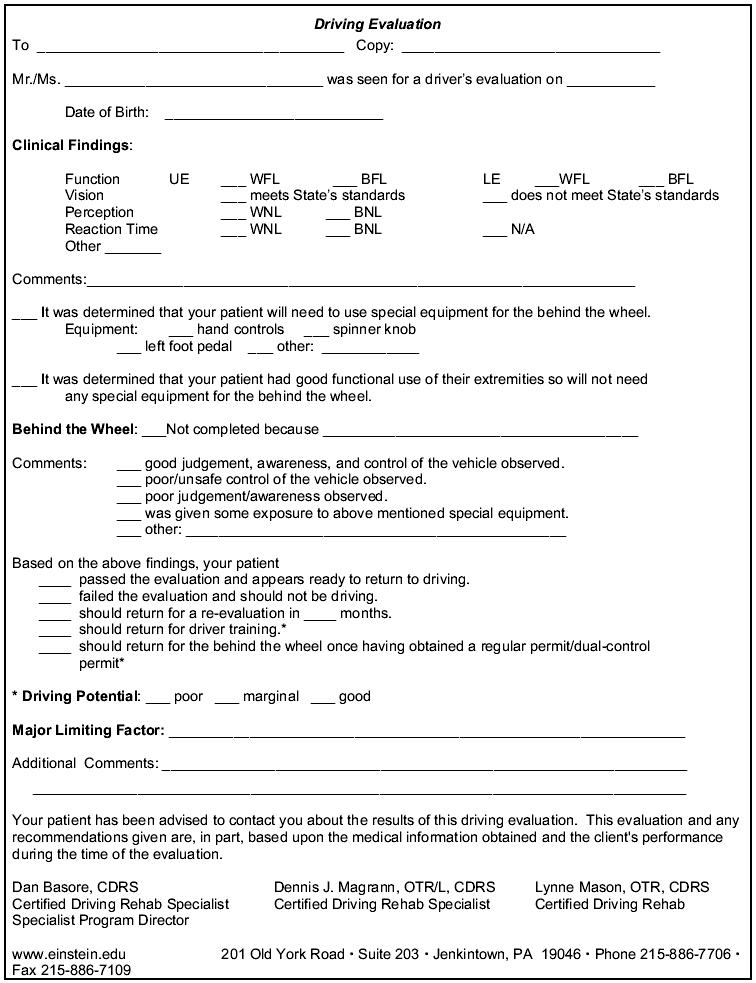

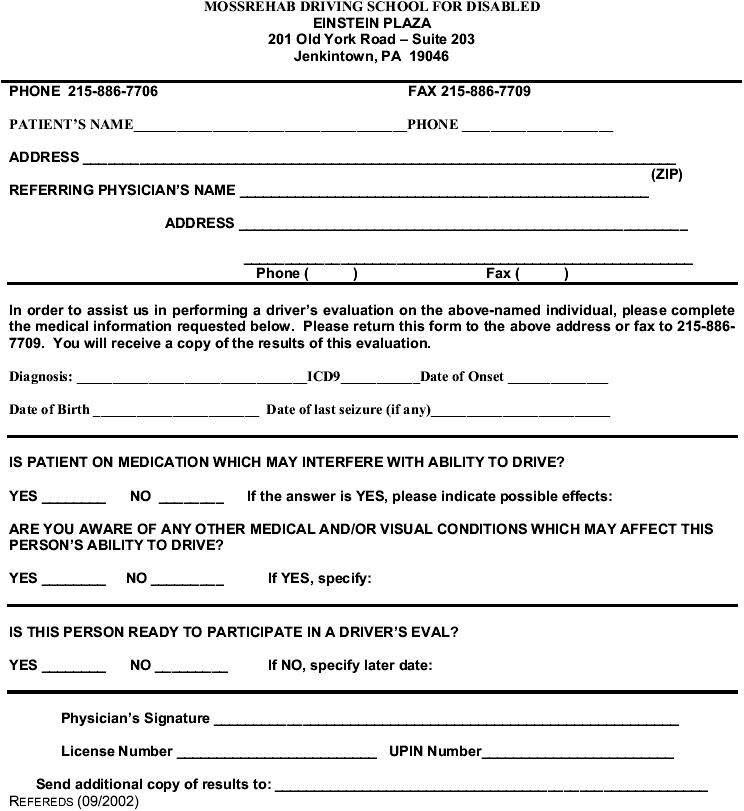

Medical referral form for driving school

Appendix 2

Driver evaluation form