Abstract

Background

Weight gain can contribute towards the development of type 2 diabetes (T2D), and some treatments for T2D can lead to weight gain. The aim of this study was to determine whether having T2D and also being obese had a greater or lesser impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) than having either of the two conditions alone.

Methods

The 2003 dataset of the Health Survey for England (HSE) was analyzed using multiple regression analyses to examine the influence of obesity and T2D on HRQoL, and to determine whether there was any interaction between these two disutilities.

Results

T2D reduced HRQoL by 0.029 points, and obesity reduced HRQoL by 0.027 points. There was no significant interaction effect between T2D and obesity, suggesting that the effect of having both T2D and being obese is simply additive and results in a reduction in HRQoL of 0.056.

Conclusions

Based on analysis of HSE 2003 data, people with either T2D or obesity experience significant reduction in HRQoL and people with both conditions have a reduction in HRQoL equal to the sum of the two independent effects. The effect of obesity on HRQoL in people with T2D should be considered when selecting a therapy.

Background

Obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are two world health concerns of pressing importance, with the prevalence of both increasing at a startling rate. It is estimated by the International Diabetes Foundation (IDF) that the that the global number of adults with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) or T2D will grow from 248 million in 2007 to 380 million in 2025.Citation1 Currently, in developed countries, 85% to 95% of people with diabetes have T2D, and in developing countries the proportion with T2D (compared with T1D) is higher.Citation1,Citation2 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that in 2005 there were more than 400 million obese adults, with body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2, and 1.6 billion overweight adults.Citation3 According to the latest Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) estimates, the prevalence of T1D and T2D in England was 3.9% in 2008 (data for T2D alone are not recorded, but are approximately 90% of all cases) and the prevalence of obesity was 7.66% – the prevalence of both are increasing each year.Citation4

Both T2DCitation5 and obesityCitation6 reduce HRQoL. The gravest affect of T2D is due to the macro- and micro-vascular complications which usually develop as the disease progresses.Citation7,Citation8 Obese people suffer from impaired HRQoL due to specific problems relating to mobility, pain, and/or discomfort,Citation9 but also as a result of increased risk of T2D, coronary heart disease (CHD), and hypertension.Citation6,Citation10

Obesity and T2D are also closely related, since obesity is the largest risk factor for developing T2D.Citation11 Therefore, first-line intervention in the management of T2D includes diet and exercise in an attempt to promote weight loss. Unfortunately, however, many of the agents available for the management of T2D often lead to weight gain.Citation12,Citation13 Thus knowledge of the relationship between T2D, obesity and HRQoL is desirable.

Several studies have separately investigated weight or diabetes and their effect on HRQoL, but the available literature examining the simultaneous effects of weight and diabetes on HRQoL is limited.Citation14 Cross-sectional data are needed to extend the knowledge in this area.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between obesity, T2D, and HRQoL in a real-world setting in the general population of England.

Methods

We used data collected during the Health Survey for England (HSE) 2003.Citation15 The HSE is a series of annual surveys, commissioned by the UK Department of Health, which covers people living in private households in England. Data collection for HSE 2003 involved an interview, followed by a visit from a specially trained nurse, and included weight and height measurements, as well as further questioning.

Each year the HSE focuses on a different demographic group and looks at health indicators such as cardiovascular disease, physical activity, eating habits, oral health, accidents, and asthma. The 2003 survey had a primary focus on cardiovascular problems and a secondary focus on diabetes. It also included the EQ-5D questionnaire,Citation16 a generic health-related quality-of-life measure. The HSE 2003 dataset therefore contained all the parameters for studying the effects of weight, diabetes, confounding illness, and social factors on HRQoL.

The EQ-5D questionnaire is standardized for use as a measure of HRQoL. It provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. Each of the five domains consists of three levels (ie, rated by individuals as ‘no problems’, ‘some/moderate problems’, or ‘extreme/severe problems’). The five domains of the EQ-5D are: mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. An individual with no problems in any domain would have a score of 1.0. A lower score is recorded if the individual has lower HRQoL, and death is scored as 0.0. Values below zero can exist, if in a given situation, death is considered favorable to life in that given health state. To derive utilities, each health state has been assigned a value based on a UK time-trade-off survey.Citation17

During data collection for HSE 2003, participants in the survey were asked if they had diabetes, but not whether they had T1D or T2D. A post-hoc interpretation was applied by those collecting the data, whereby if a participant was receiving insulin at the time of interview, and had been diagnosed with diabetes before their 35th birthday, they would be categorized as having T1D. Otherwise they were categorized as having T2D. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and overweight as BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 according to the WHO classification.Citation3,Citation11

The original HSE 2003 dataset (18,553 responses) was purged of records from participants that did not receive the EQ-5D questionnaire (those < 16 years old), or did not complete it; who had T1D; or did not provide measurements needed to calculate BMI. Also discarded were: data from participants who failed to inform about smoking status, cardiovascular disease history, blood pressure, history of long standing, or recent acute illnesses, and participants who did not fill out the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (which is designed to predict the need for psychological help).Citation18 The GHQ is a validated, self-administered, 12-items questionnaire focusing on the inability to carry out normal functions and the appearance of new and distressing phenomena.Citation19 After purging the dataset, the final number of respondents included in the analyses was 12,188, of which 373 (3.1%) had T2D.

A multiple linear regression model, consisting of variables describing several factors such as physical and mental well-being, and socio-economic status, and including information on diabetes and BMI, was developed for this study. In the model, HRQoL was dependent on socio-economic and health factors and, for analytical purposes, the focus was on variables for weight and diabetes.

The dataset was analyzed using multiple linear regression analysis to examine the influence of obesity and T2D on HRQoL. Age and gender were retained, even if they became statistically insignificant. Whether or not all other variables were retained depended on the statistical tests. The interaction between the two disutilities, diabetes and obesity, was analyzed to determine whether being obese and having T2D had a further effect beyond the additive effects of having each condition.

The regression model also included variables for socioeconomic status (income), as well as lifestyle indicators affecting health (smoking), and multiple indicators of health status and wellbeing. An acute illness variable described any recent medical history, and a GHQ score measured mental wellbeing. Comorbidity variables contained various long-term medical conditions that could affect HRQoL (such as kidney disease, rheumatism, asthma, back problems, bronchitis, cancer, epilepsy, hearing problems, ulcer, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension; ). When testing for statistical significance, some variables were treated as groups (income, smoking, acute illness, and GHQ). Comorbidities were tested individually.

Results

Demographics

T2D was primarily present in participants over 40 years of age, and most frequently in people over 60 years (). Approximately 50% of people with T2D were also obese, and normal weight individuals had the lowest prevalence of T2D. The trend of higher T2D prevalence with higher BMI group was consistent across age groups, with the exception of the 16–29 year age group, where very small numbers of people with T2D produced inconsistent results, as shown in .

Table 1 Number and proportion of people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) per age and weight group in Health Survey for England 2003

Regression analysis

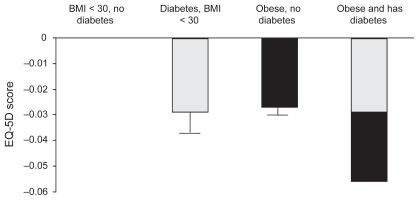

In the model, both T2D and obesity had significant, independent effects on HRQoL, measured by the EQ-5D. Having T2D reduced HRQoL by 0.029 points and obesity reduced HRQoL by 0.027 points. The analysis showed no significant interaction effect between T2D and obesity. The effect of having both conditions is simply the sum of each individual effect (−0.056; ).

Figure 1 Effect of type 2 diabetes and obesity on health-related quality of life measured by EQ-5D.

Compared with people whose income was in the lowest fifth of the population, people with higher incomes tended to have a better HRQoL.

Compared with current smokers, people who had stopped smoking, or never started, had a statistically better HRQoL.

Recent suffering from an acute illness, reduced health-related HRQoL, and participants who had a high score on the GHQ (indicating mental problems) also had reduced HRQoL. Having other co-morbidities decreased HRQoL, except for hearing problems, which had a positive effect on HRQoL. Also, HRQoL decreased as people got older ().

Table 2 Overview of results from the regression model

Discussion

This study showed that obese people (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) had a lower HRQoL than non-obese people, regardless of whether they have T2D or not. People with T2D, with normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), or obesity, had a lower HRQoL than those in the same weight groups, without the disease. However, the effect of obesity and T2D is purely additive, with no positive or negative effects of having both conditions at the same time.

These results support those from previous investigations of the impact on HRQoL of obesity and T2D.Citation20 A study by MacranCitation9 that also used HSE data (1996) to examine the relationship between weight (BMI) and HRQoL (with HRQoL quantified according to EQ-5D) found a significant difference in HRQoL between BMI categories, although results differed by gender. For women, but not men, there was a significant decrease in utility scores with increasing BMI, when adjusted for age and longstanding illness.Citation9

In a study by Lee et al,Citation21 increasing BMI was found to reduce utility in each of the three groups T1D, T2D, and no diabetes. The effect of both BMI and diabetes on utility was significant. There was no significant difference in the effect of obesity on utility between those with and without diabetes.

A recent review of 18 articles investigating the impact of change in body weight on people’s utility scores found that utility decreased as body weight increased, regardless of the scoring system used, or the population.Citation14 The review also found that the change in utility score per unit change in BMI, was slightly higher in people with diabetes than in people without diabetes.Citation14 Our results support the findings of Matza et al,Citation22 who showed that a 3% higher weight (as a treatment-related attribute) was accompanied by a reduction in HRQoL of 0.04 points.

The reduction in HRQoL associated with having T2D and obesity shown in this study was similar to the impact of aging several decades, or going from having an income in the second highest quintile to being in the lowest quintile. The impact was slightly lower than the impact of a foot ulcer and slightly greater than the impact of a cardiovascular event.

Although neither T2D nor obesity was correlated with an increase in the risk of problems in the EQ-5D sub-model on anxiety (results not shown), people with a high GHQ score (ie, people who reported a need for psychological help), had lower HRQoL. GHQ score could to some extent, be seen as a proxy for anxiety issues stemming from other sources, such as diabetes and obesity. This would support results from the Diabetes Attitudes Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study, in which people reported they would feel a sense of self-blame if they had to start insulin therapy.Citation23 The IDF currently recommends that well-being and psychological status are periodically tested in people with T2D, either by questioning or using a formal instrument.Citation24

The effect of obesity on HRQoL in people with T2D should be considered when selecting a therapy. Where possible, preference should be given to therapeutic interventions that have a minimal impact on weight gain. In the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), weight gain was found to be significantly higher in people with T2D receiving intensive treatment than in those receiving conventional treatment.Citation25 It is recognized that different treatments can have different effects in weight gain – biguanides, α-glucosidase inhibitors, GLP-1 agents, and some insulin analogues are the least likely to cause weight gain and may be associated with weight loss.Citation13,Citation26 The results of the multinational DAWN studyCitation27 show that that one of the priorities among patients with T2D was the avoidance of weight gain.

People with T1D made up almost a quarter of people with diabetes in HSE 2003, compared with the European norm of 4% to 5%,Citation28 indicating that the interpretation may have classified too many people as having T1D. However, any choice of age limit as a means of distinguishing between diabetes types will tend to be arbitrary and some degree of misclassification is unavoidable. For the purpose of this article the chosen standard for the HSE 2003 was used, but we noted the potential for misclassification and acknowledge that this is one of the limitations of the analysis. However, we do not believe that any misclassification would have had a substantial impact on the overall findings of this analysis.

The HSE dataset analyzed in the current study did not include people in institutions, which is likely to have resulted in a relatively lower representation of the older population, particularly those with disabilities and severe illness. Non-inclusion of this population in our assessment could have led to an underestimation of the mean impact on HRQoL of both obesity and diabetes.

The prevalence of T2D was only 3.1% in the purged dataset, compared with 3.9% in the UK population in 2003.Citation1 However, it was considered that the remaining people with diabetes were representative of the group as a whole, and therefore, the selection bias would not exaggerate the results in the model. Similarly, approximately 34% of the HSE 2003 population was excluded, introducing the possibility of non-response bias. However, most people excluded from the analysis were children (<16 years old; 58% of those excluded) who did not complete the EQ-5D and would not have been classified as T2D patients in our analysis.

Conclusions

The results of this study of data from HSE 2003 show that having T2D and being obese, as individual conditions, reduce HRQoL significantly, but that the effect of having both conditions is purely additive. When we consider that many treatments for T2D cause weight gain, the effect of a treatment-related increase in weight on the HRQoL of people with T2D should be taken into account when choosing treatment. In future, longitudinal data may provide information on the effect on HRQoL of treatment-associated weight gain on people with T2D.

Authors’ contributions

SG contributed to the conception and design of the study, the interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript. NK, UJP and MH contributed to the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Novo Nordisk A/S. The Health Survey for England 2003 was carried out by the Joint Health Surveys Unit (University College London and the National Centre for Social Research). The Health Survey for England was funded by the Department of Health. Editorial assistance was provided by ESP Bioscience (Sandhurst, UK) on behalf of Novo Nordisk A/S.

Disclosures

SG has received funds for research, a fee for speaking and fees for consulting from Novo Nordisk. NK, UJP and MH are all employees of Novo Nordisk A/S.

References

- Chapter 1Diabetes Atlas3rd edInternational Diabetes Federation200619

- The global burden of diabetesDiabetes Atlas2nd edInternational Diabetes Federation200315111

- WHO fact sheet (No. 311) on obesity and overweight URL: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.htmlAccessed 4 September 2009

- QOF ReportsDiabetes p–2008 URL: http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Professionals/Information_resources/Reports/Diabetes-prevalence-2008/Accessed 4 September 2009

- RubinRRPeyrotMQuality of life and diabetesDiabetes Metab Res Rev19991520521810441043

- KolotkinRLCrosbyRDWilliamsGRHartleyGGNicolSThe relationship between health-related quality of life and weight lossObesity Res20019564571

- GraueMWentzel-LarsenTHanestadBRBatsvikBSovikOMeasuring self-reported health-related quality of life in adolescent with type 1 diabetes using both generic and disease specific instrumentsActa Paediatr2003921190119614632337

- CoffeyJTBrandleMZhouHValuing health-related quality of life in diabetesDiabetes Care2002252238224312453967

- MacranSThe relationship between body mass index and health-related quality of lifeCentre for Health Economics, University of York2004 Discussion paper 190

- JiaHLubetkinEIThe impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US populationJ Public Health (Oxf)20052715616415820993

- JamesWPTJackson-LeachRMhurduCNOverweight and obesityEzzatiMLopezADRodgersAMurrayCJLComparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk FactorsWHO2003

- AACE/ACE: Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Management of Diabetes MellitusEndocr Pract200713Suppl 1368

- HermansenKMortensenLSBodyweight changes associated with antihyperglycaemic agents in type 2 diabetes mellitusDrug Saf2007301127114218035865

- DennettSLBoyeKSYurginNRThe impact of body weight on patient utilities with or without Type 2 diabetes: a review of the medical literatureValue Health20081147848618489671

- Health Survey for England 2003 URL: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_4098712Accessed 07 February 2007

- The Euroqol Group: Euroqol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of lifeHealth Policy19901619920810109801

- DolanPGudexCKindPWilliamsAA social tariff for EuroQol: results from a UK general population surveyCentre for Health Economics, University of York1995 Discussion paper 138

- GoldbergDWilliamsPAUser’s Guide to the General Health QuestionnaireWindsor, UKNFER-Nelson1998

- PevalinDJMultiple applications of the GHQ-12 in a general population sample: an investigation of long-term retest effectsSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiology200035508512

- BradleyCSpeightJPatient perceptions of diabetes therapy: assessing quality of lifeDiabetes Metab Res Rev200218S64S6912324988

- LeeAJMorganCLIMorisseyMWittrup-JensenKUKennedy-MartinTCurrieCJEvaluation of the association between EQ-5D index (health-related utility) and body mass index (obesity) in hospital-treated people with type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes and no diagnosed diabetesDiabet Med2005221482148616241910

- MatzaLSBoyeKSYurginNUtilities and disutilities for type 2 diabetes treatment-related attributesQual Life Res2007161251126517638121

- PeyrotMRubinRRLauritzenTResistance to insulin therapy among patients and providers. Results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) studyDiabetes Care2005282673267916249538

- IDF Clinical Guidelines Task Force: Chapter 4, Psychological careGlobal Guideline for Type 2 Diabetes20051921

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) GroupIntensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33)Lancet19983528378539742976

- NathanDMBuseJBDavidsonMBMedical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapyDiabetes Care20093219320318945920

- RubinRRPeyrotMSiminerioLMHealth care and patient-reported outcomes: results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) studyDiabetes Care2006291249125516732004

- AmosAFMcCartyDJZimmetPThe rising global burden of diabetes and its complications: estimates and projections to the year 2010Diabet Med199714S7S85