Abstract

Background:

Anthroposophic treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) includes special artistic and physical therapies and special medications.

Methods:

We studied 61 consecutive children starting anthroposophic treatment for ADHD symptoms under routine outpatient conditions. Primary outcome was FBB-HKS (a parents’ questionnaire for ADHD core symptoms, 0–3), and secondary outcomes were disease and symptom scores (physicians’ and parents’ assessment, 0–10) and quality of life (KINDL® total score, 0–100).

Results:

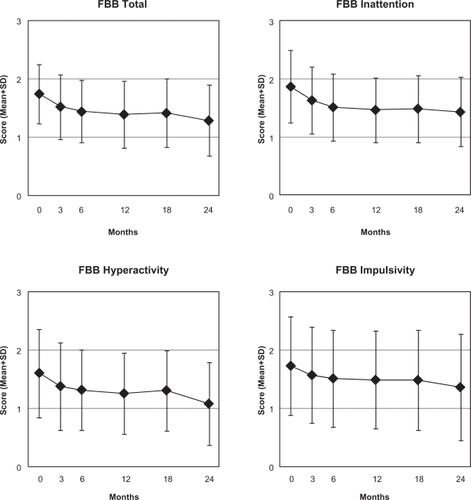

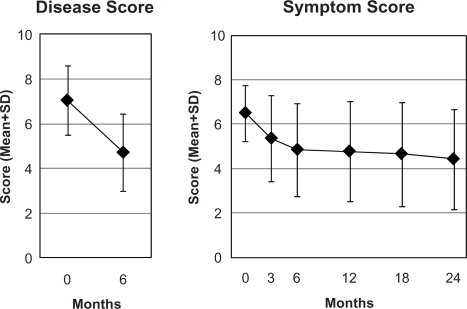

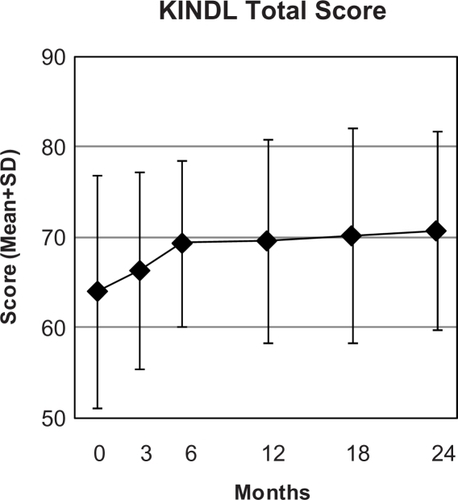

A total of 67% of patients fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, 15% had an exclusion diagnosis such as pervasive developmental disorders, while 18% did not fulfill ADHD criteria for another reason. Anthroposophic treatment modalities used were eurythmy therapy (in 56% of patients), art therapy (20%), rhythmical massage therapy (8%), and medications (51%). From baseline to six-month follow-up, all outcomes improved significantly; average improvements were FBB-HKS total score 0.30 points (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.18–0.43; P < 0.001), FBB-HKS inattention 0.36 (95% CI: 0.21–0.50; P < 0.001), FBB-HKS hyperactivity 0.29 (95% CI: 0.14–0.44; P < 0.001), FBB-HKS impulsivity 0.22 (95% CI: 0.03–0.40; P < 0.001), disease score 2.33 (95% CI: 1.84–2.82; P < 0.001), symptom score 1.66 (95% CI: 1.17–2.16; P < 0.001), and KINDL 5.37 (95% CI: 2.27–8.47; P = 0.001). Improvements were similar in patients not using stimulants (90% of patients at months 0–6) and were maintained until last follow-up after 24 months.

Conclusion:

Children with ADHD symptoms receiving anthroposophic treatment had long-term improvement of symptoms and quality of life.

Background

Symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity are reported in 8%–16% of children,Citation1,Citation2 and 5% of all children fulfill the diagnostic criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).Citation3 ADHD can affect self-esteem, social skills, parent–child relationships, and school performance, and is associated with psychiatric comorbidity.Citation4–Citation6 In clinical trials, central stimulants and related medications improve ADHD symptoms.Citation7 However, up to 30% of children do not respond to or do not tolerate stimulants due to adverse effects,Citation8 and less than 10% continue with stimulants after one year.Citation9 Psychosocial interventions are less effective than medications but provide modest benefits as add-ons.Citation10,Citation11 Up to two-thirds of children with ADHD use complementary or alternative therapies,Citation12 sometimes provided by their physicians.

Anthroposophic medicine (AM) is a complementary system of medicine, founded by Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman.Citation13 AM is provided by specially trained physicians in 56 countries worldwide.Citation14 AM extends the conception of human physiology beyond cellular and molecular mechanisms to holistic interactions of overriding functional systems (downward causality).Citation15 In particular, a complex equilibrium exists between two polar systems, ie, the “nerve-sense system” (low metabolic rate, mediator of consciousness) and the “metabolic-limb system” of the abdominal organs and limbs (high metabolic rate, minimal consciousness, mediator of voluntary movement).Citation16 This equilibrium can be distorted in human disease. For example, the ADHD symptom of hyperactivity is seen to reflect a predominance of the metabolic-limb system.Citation17 This imbalance is sought to be regulated by special AM therapies (eurythmy movement exercises, art therapy, rhythmical massage therapy) and special AM medications.Citation17–Citation19

Eurythmy (Greek, meaning “harmonious rhythm”) therapy is an active exercise therapy involving cognitive, emotional, and volitional elements.Citation20 During eurythmy therapy sessions, patients are instructed to perform specific movements with the hands, feet or whole body. Eurythmy movements are related to the sounds of vowels and consonants, to music intervals or to soul gestures, eg, sympathy-antipathy.Citation21 A eurythmy therapy cycle usually consists of 12–15 sessions of 45 minutes each, administered once weekly.Citation22 Between therapy sessions the patients perform eurythmy movements daily.

In AM art therapy, the patients engage in painting, drawing, clay modeling, music, or speech exercises.Citation16 An AM art therapy cycle usually consists of 12 sessions of 45 minutes each, administered once weekly.Citation23 In addition to psychologic effects (eg, activation, emotive expression, dialogic communication with the therapist and with the artistic medium),Citation24,Citation25 AM art therapy can induce physiologic effects, eg, AM speech exercises have effects on heart rate rhythmicity and cardiorespiratory synchronization which are not induced by spontaneous or controlled breathing alone.Citation26,Citation27 Eurythmy exercises have similar effects.Citation28

Rhythmical massage therapy was developed from Swedish massage by Ita Wegman, a physician and physiotherapist.Citation29 In rhythmical massage therapy, traditional massage techniques (effleurage, petrissage, friction, tapotement, vibration) are supplemented by gentle lifting and rhythmically undulating, stroking movements, where the quality of grip and emphasis of movement are altered to promote specific effects.Citation30 A rhythmical massage therapy cycle usually consists of 6–12 sessions administered once or twice weekly, each session lasting 20–30 minutes and followed by a rest period of at least 20 minutes.Citation31 Most patients can be treated with one cycle of art, eurythmy, or massage therapy, while prolonged treatment may be necessary for some patients with severe or persistent disease.

AM medications are prepared from plants, minerals, animals, and from chemically defined substances, and can be prepared in concentrated or potentized form. Potentization implies a successive dilution, each dilution step involving a rhythmical succussion (repeated shaking of liquids) or trituration (grinding of solids into lactose monohydrate). For example, a D6 potency (also called 6×) has been potentized in a 1:10 dilution six times, resulting in a 1:10−6 dilution.Citation32 Because potencies beyond D23 do not contain any molecules of the original substance, effects cannot readily be explained by molecular mechanisms. However, a systematic review of in vitro studies found biologic effects of potencies ≥D23 in nearly three-quarters of the studies and in more than two-thirds of the studies with highest quality.Citation33 All AM medications are manufactured according to Good Manufacturing Practice and national drug regulations. Quality standards of raw materials and manufacturing methods are described in the Anthroposophic Pharmaceutical Codex.Citation32 Toxicologically relevant starting materials (eg, belladonna, lead) are highly diluted according to the safety requirements of European regulations. The available evidence suggests that AM medications and therapies are generally well tolerated, with infrequent adverse reactions of mostly mild to moderate severity.Citation34,Citation35

Prior to prescription of AM medications or referral to AM therapies, AM physicians have prolonged consultations with the patients and their caregivers. These consultations are used to take an extended history, to address constitutional and psychosocial aspect of the patients’ illness, to explore the family’s preparedness to engage in treatment, and to select optimal therapy for each patient.Citation16,Citation30

AM therapy providers (physicians, physiotherapists, eurythmy therapists, art therapists) are certified following structured training programs according to international, standardized curricula. Therapy guidelines exist for AM medical therapy,Citation36 eurythmy therapy,Citation37 and AM art therapy.Citation23

Related to the AM approach is an educational philosophy implemented in more than 3000 Waldorf schools, kindergartens, and curative education centers worldwide, many of which provide AM therapies.Citation38,Citation39

AM treatment for children with ADHD symptoms aims at general and specific effects. AM art and eurythmy exercises aim to develop concentration, awareness of feelings, and motor skills,Citation20,Citation40 whereas rhythmical massage therapy works through sensory stimulation. All three therapy modalities (art, eurythmy, rhythmical massage) aim at psychologic effects from verbal and nonverbal communication with therapists, while all AM treatment aims to regulate the equilibrium between the nerve-sense system and the metabolic-limb system. In addition, AM treatment aims at more specific effects on individual ADHD symptoms and constitutional features by employing specific art therapy modalities, specific eurythmy movements, specific massage techniques, specific massage movement patterns, and specific AM medications (further descriptions are availableCitation17–Citation19,Citation21,Citation29,Citation31). AM medications do not contain chemicals with stimulant properties, such as for conventional central nervous system sympathomimetics.

AM physicians treating children with ADHD symptoms will give information and advice to the family, teachers, and other caregivers about the condition, natural history, coping and management strategies, and treatment options, and they will assess the kindergarten or school situation.Citation17,Citation19,Citation41,Citation42 In addition, the physicians will choose among the available AM therapy modalities, including a broad range of AM medications, in order to tailor treatment to the individual needs of the patient. Similar to recent guideline recommendations,Citation41,Citation42 stimulants are not used as initial therapy for moderate ADHD. In severe or nonresponsive ADHD, however, AM therapies are often combined with stimulants.Citation19 In this respect, there has been some debate among AM physicians as to the degree of severity necessitating stimulant therapy.Citation43–Citation45

Two small single-center studies have evaluated AM painting/drawing/clay therapyCitation46 and eurythmy therapyCitation20 for ADHD. We present here a preplanned subgroup analysis of children with ADHD symptoms from a multicenter study of a broader range of AM therapy options (all artistic therapy modalities, eurythmy therapy, rhythmical massage, and medications).Citation47

For complementary therapy systems in widespread use, regardless of whether evidence from randomized trials exists, it has been argued that the conventional drug research strategy, starting with studies of biologic mechanisms and moving through Phase I, II, and III clinical trials, is not optimal.Citation48 Another more appropriate strategy has been proposed, moving from descriptive studies (Phase I) towards comparative studies of the whole system and its parts, and ending with studies of biologic mechanisms (Phase V).Citation48 In the context of this reversed strategy, the present analysis addressed topics in the Phases I and II (therapy paradigms, therapy use, clinical outcomes, perceived benefit, and safety).

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective, observational, two-year, cohort study in a routine outpatient medical setting. The study was part of a research project on the effectiveness, costs, and safety of AM therapies in outpatients with chronic disease (Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study [AMOS]).Citation47,Citation49 The AMOS project was initiated by a health insurance company in conjunction with a health benefit program. The present preplanned subgroup analysis concerned a subgroup of children with ADHD symptoms. Since only limited data on AM treatment for this indication were available,Citation20,Citation46 the primary objective was to describe the AM therapy for ADHD symptoms (spectrum of AM therapy modalities used, extent of combination with conventional therapy) as well as the clinical outcome under AM treatment in routine outpatient settings. Further research questions addressed adverse reactions and therapy satisfaction.

Setting, participants, and therapy

All physicians certified by the Physicians’ Association for Anthroposophical Medicine in Germany and working in an office-based practice or outpatient clinic were invited to participate in the AMOS study. Certification as an AM physician requires a completed medical degree and a three-year structured postgraduate training. The participating physicians recruited consecutive patients starting AM therapy under routine clinical conditions. AMOS patients were included in the present analysis if they fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria were: age 3–16 years; enrolment in AMOS in the period 01 April 2001 to 31 December 2005 (the primary outcome of the present analysis was not documented for AMOS patients enrolled before April 2001); ADHD symptoms of at least six months’ duration; starting AM therapy for ADHD symptoms: starting AM medical treatment (AM-related consultation of at least 15 minutes followed by new prescription of AM medication) or referral to AM therapy by a nonmedical therapist (art, eurythmy, or rhythmical massage).

Patients were excluded if they had previously received the AM therapy in question for ADHD symptoms. AM therapy was administered at the discretion of the physicians and therapists, and evaluated as a whole systemCitation50 with subgroup analysis of evaluable therapy modality groups. Therapies documented in the study were classified as AM therapy (consultations with AM physicians, AM art therapy, eurythmy therapy, rhythmical massage therapy, AM medications); conventional therapy for ADHD symptoms (central stimulants, antidepressants, psychotherapy, occupational therapy, play therapy); or other (all other therapies).

Clinical assessments

Baseline assessment

Diagnostic criteria for ADHD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) were assessed using the Diagnostic Checklist for Hyperkinetic Disorders/ADHD (DCL-HKS),Citation51 documented by the physicians. The DCL-HKS (revised version DCL-ADHS)Citation52 is a validated checklist for the diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV and ICD-10, recommended for clinical assessment of children and adolescents with ADHD symptoms in primary care.Citation8,Citation42 The DCL-HKS comprises the following items:

A total of 18 core symptoms of ADHD, ie, inattention (nine symptoms), hyperactivity (five symptoms), and impulsivity (four symptoms)

Additional ADHD criteria according to DSM-IV and ICD-10, ie, symptoms beginning before age seven years, presence in more than one situation, significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning, symptoms not explained by age, developmental condition, school strain, very high intelligence, chaotic environment, or medication

Exclusion diagnoses for ADHD according to DSM-IV or ICD-10, ie, pervasive developmental disorder, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, or other relevant psychiatric disorder.

These items are combined into an algorithm, resulting in the DSM-IV categories: ADHD combined type; ADHD predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type; ADHD predominantly inattentive type; ADHD not otherwise specified; and ADHD criteria not fulfilled, as well as in the ICD-10 categories, ie, F90 hyperkinetic disorder fulfilled/not fulfilled, with ICD-10 subtypes.

In addition to DCL-HKS, relevant current and previous comorbid disorders were documented in free text. The DCL-HKS is part of a more comprehensive diagnostic assessment system for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents (DISYPS).Citation51,Citation52 DISYPS comprises checklists for the investigation of disorders frequently coexisting with ADHD, such as conduct disorder and tics. These checklists were not used in the present study.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the FBB-HKS (German: Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Hyperkinetische Störungen) at six-month follow-up. The FBB-HKS is a validated questionnaire for core ADHD symptoms according to DSM-IV and ICD-10, documented by parents.Citation51,Citation52 The FBB-HKS consists of 20 items addressing the dimensions of inattention (nine items), hyperactivity (seven items), and impulsivity (four items). Each item is rated on a numeric rating scale from 0 (“not present”) to 3 (“very strong intensity”). Scores for the three dimensions and a FBB-HKS total score are calculated as the average of the respective items (range 0–3).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were disease severity, quality of life, satisfaction with therapy, and adverse reactions. Disease severity was documented by physicians (disease score) and parents (symptom score). Disease score was the physician’s global assessment of severity of ADHD symptoms using a numeric rating scaleCitation53 from 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”). Symptom score was a compound measure of the symptoms for which the parents had sought medical attention for their children. At baseline, the parents documented one to six symptoms in order of decreasing importance and assessed the intensity of each symptom on a numeric rating scale from 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”).Citation53 At each follow-up, the parents documented the intensity of the same symptoms which they had documented at baseline. Symptom score was the average severity of all documented symptoms per patient at each documentation point. This score has not been validated.

Quality of life was assessed by the parents of children aged 3–7 years and by children aged 8–16 years, using the KINDL® questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents, total quality of life score (range 0–100).Citation54

Therapy outcome rating (numeric rating scale 0–10), satisfaction with therapy (numeric rating scale 0–10), and therapy effectiveness rating (“very effective”, “effective”, “less effective”, “ineffective”, or “not evaluable”) were documented by parents (effectiveness rating also by physicians) after six and 12 months.

Adverse reactions to medications or therapies were documented by parents after six, 12, 18, and 24 months and by the physicians after six months. The documentation included suspected cause, intensity (mild/moderate/severe reflecting no/some/complete impairment of normal daily activities, respectively), and therapy withdrawal because of adverse reactions. Serious adverse events were documented by the physicians throughout the study.

Data collection

All data were documented using questionnaires. Questionnaires used at study enrolment were handed out by the physicians, and follow-up questionnaires were issued from the study office by post. All questionnaires were returned in sealed envelopes to the study office. The physicians documented eligibility criteria, DCL-HKS, and prescription of AM therapy at baseline. The therapists documented AM therapy administration (the implementation of each therapy session was confirmed by signatures of therapists as well as parents or patients). All other items were documented by parents unless otherwise stated. Parent responses were not made available to the physicians. The diagnostic categorization of patients with respect to ADHD criteria, based on the algorithm in DCL-HKS, was performed in the study office and not by the physicians. The physicians were compensated 60 Euro per included and fully documented patient, while the patients received no compensation.

FBB-HKS, symptom score, and KINDL were documented after 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Disease score was documented after 0 and six months. Medication use was documented with name of medication, administration frequency (daily, 3–6 days per week, 1–2 days per week, 1–3 days per month, <one day per month), and duration of use.

The data were entered twice by two different persons into Microsoft® Access 97 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond WA). The two datasets were compared, and discrepancies were resolved by checking with the original data.

Quality assurance, adherence to regulations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine Charité, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany, and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and largely following the International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrolment. Monitoring visits, including source data verification, were performed for all physicians enrolling at least five patients into the AMOS study in the recruitment period for the present sample (58/61 patients in the present sample).

Data analysis

The data analysis was performed on all patients fulfilling the eligibility criteria, using SPSS® 14.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and StatXact® 5.0.3 (Cytel Software Corporation, Cambridge, MA). The t-test was used for continuous data. The McNemar test and Fisher’s exact test were used for binominal data. All tests were two-tailed. Missing values for clinical outcomes at follow-up assessments were replaced by the last value carried forward.

In the main analyses, clinical outcomes were analyzed with 0–6 month (primary assessment) and 0–24 month pre-post comparisons. In an alternative set of analyses, clinical outcomes were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) testing for within-subject change between the time points 0, three and six months, and 0 and 12, 18, and 24 months, respectively. Results were very similar to the pre-post analyses, and are not presented.

Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Since this was a descriptive study, no adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed.Citation55 Pre-post effect sizes were calculated as standardized response mean (= mean change score divided by the standard deviation of the change score) and classified as minimal (<0.20), small (0.20–0.49), medium (0.50–0.79), and large (≥0.80).Citation56,Citation57

In a preplanned subgroup analysis of the primary outcome, the sample was restricted to patients not using non-AM adjunctive therapies during the first six study months. Adjunctive therapies analyzed were medications (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification Index: N06BA centrally acting sympathomimetics, N06A antidepressants), psychotherapy, occupational therapy, and play therapy. Post hoc subgroup analyses were performed on evaluable diagnostic groups and AM therapy modality groups.

Results

Participating physicians and therapists

The patients were enrolled by 19 physicians (16 general practitioners and three pediatricians). Comparing these physicians with AM-certified general practitioners and pediatricians in Germany without study patients (n = 282), no significant differences were found regarding gender (47.4% versus 57.1% males), age (mean 47.1 ± 6.4 versus 48.1 ± 8.0 years), number of years in practice (17.9 ± 7.0 versus 18.9 ± 8.8 years) or the proportion of physicians working in primary care (94.7% versus 98.6%).

The patients were treated by 30 different AM therapists (art, eurythmy, and rhythmical massage). Comparing these therapists with certified AM therapists in Germany without study patients (n = 1140), no significant differences were found regarding gender (76.7% versus 81.1% females), age (mean 47.8 ± 7.7 versus 50.3 ± 9.5 years) or the number of years since therapist qualification (10.8 ± 6.8 versus 13.1 ± 8.7 years).

Patient recruitment and follow-up

From 01 April 2001 to 31 December 2005, a total of 69 patients aged 3–16 years starting AM therapy for ADHD symptoms were assessed for eligibility. Of these patients, 61 fulfilled all eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. Eight patients were not included because of eligibility criteria not being fulfilled (n = 2, because of previous study participation [n = 1] and ongoing use of the trial AM therapy [n = 1]), patients’ baseline questionnaire missing (n = 5), and physician’s baseline questionnaire received longer than two months after enrolment (n = 1).

A total of 64% (n = 39/61) of patients were enrolled by general practitioners and 36% (n = 22/61) by pediatricians. The physicians’ settings were primary care practices (72% of evaluable patients, n = 41/57), referral practices (16%, n = 9), and outpatient clinics (28%, n = 16). Each physician enrolled 1–2 patients (n = 12 physicians), 3–5 patients (n = 3), or >5 patients (n = 2), with a range of 1–16 patients enrolled per physician. The last patient follow-up was on 16 February 2008.

The parents were administered a total of 305 follow-up questionnaires, out of which 245 (80.3%) were returned. Follow-up rates were 95% (n= 58/61), 87%, 77%, 72%, and 71% after three, six, 12, 18, and 24 months, respectively. At least one follow-up questionnaire was returned in 97% (59/61) of patients.

Respondents (n = 47) and nonrespondents (n = 14) in the 12-month patient-follow-up did not differ significantly regarding age, gender, diagnosis, disease duration, baseline FBB-HKS total score, baseline disease score, or baseline symptom score. A corresponding comparison for the six-month follow-up was not performed because of the low number of nonrespondents (n = 8). The corresponding comparison for the 24-month follow-up showed no significant differences regarding age, gender, diagnosis, disease duration, or baseline symptom score, while significant differences were found for baseline FBB-HKS total score (0.43 points higher in nonrespondents than in respondents, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.16–0.70; P = 0.002) and baseline disease score (1.25 points higher in nonrespondents, 95% CI: 0.44–2.06; P = 0.003). The physician six-month follow-up documentation was available for 97% (59/61) of patients.

Baseline characteristics

Sociodemographic data

The patients were recruited from 11 of 16 German federal states. Mean age was 8.9 ± 3.3 years (range 3.4–16.8); a total of 84% (51/61) of the patients were boys. Mean household size, including the patient, was 3.9 ± 1.2 persons (range 2–8). Further sociodemographic data are presented in .

Table 1 Sociodemographic data

Disease status

The duration of ADHD symptoms was 6–11 months in 3% (n = 2/61) of patients, 1–4 years in 62% (n = 38) and ≥5 years in 34% (n = 21), with a median symptom duration of 3.0 years (range 0.5–10.0, mean 3.7 ± 2.0 years).

A total of 67% (n = 41/61) of patients fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, 15% (n = 9) had an exclusion diagnosis such as pervasive developmental disorders, and 18% (n = 11) did not fulfill the ADHD criteria for another reason (). A total of 28% (n = 17/61) of patients fulfilled the ICD-10 research criteria for F90 hyperkinetic disorders. The FBB-HKS total score at baseline was 1.79 ± 0.47 in boys (n = 50), 1.50 ± 0.60 in girls (n = 10), and 1.74 ± 0.50 in the whole sample.

Table 2 Diagnoses in study participants

A current comorbid mental disorder (ICD-10 F00-F99) was present in 17% (n = 11/61) of patients, with F41 anxiety disorders in four patients and seven different other diagnoses in seven patients. A current comorbid physical diagnosis (not ICD-10 F00-F99) was present in 57% (35/61) of patients, with a median of 1.0 (inter-quartile range [IQR] 0–1, range 0–3) comorbid physical diagnoses. The most common comorbid physical diagnoses were R00-R99 symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (37%, 19/52 diagnoses), J00-J99 diseases of the respiratory system (13%, n = 7), and L00-L99 diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (13%, n = 7). According to the physician, a mental disorder was suspected in one or both parents of 16% (n = 10/61) of patients, while familial instability or partner conflicts were suspected in 39% (n =24).

Therapy

Anthroposophic therapies

Patients received AM medical treatment alone (n = 4) or were referred to AM art, eurythmy, or rhythmical massage therapy without medical treatment (n = 21), or were referred to AM therapy with medical treatment (n = 36).

Among patients receiving medical treatment (n = 40), the duration of the consultation with the AM physician at study enrollment was 15–29 minutes (n = 16 patients), 30–44 minutes (n =9), 45–59 minutes (n =6), and ≥60 minutes (n =9).

Among patients starting medical treatment (n = 40) a total of 56 different AM medications were prescribed at enrollment. The most frequent medications were Aurum/Stibium/Hyoscyamus pillules (prescribed to four patients), Aurum Comp pillules (n = 3) and Cichorium Plumbo Cultum Rh D3 liquid (n = 3). The most frequent starting materialsCitation32 were Aurum naturale (n = 12), Plumbum metallicum (n = 6), Cichorium intybus (n = 5), and Bryophyllum = Kalanchoe pinnata (n = 4).

Among the 57 patients referred to AM therapy, 89% (n = 51) had the planned AM therapy, while for 11% (n = 6) the AM therapy documentation is incomplete. AM therapies used were eurythmy therapy (n = 34 patients), rhythmical massage therapy (n = 5), and art therapy (n = 12) with the therapy modalities painting/drawing/clay (n = 2), speech exercises (n = 6), and music (n = 4). The AM eurythmy/art/massage therapy started at a median of six (IQR 2–21) days after enrolment. Median therapy duration was 102 days (IQR 79–203 days), and median number of therapy sessions was 13 (IQR 11–20). Median number of days between therapy sessions was eight days (IQR 6–11 days).

Conventional therapies

During the 12 months preceding study enrollment, central stimulants had been used by 15% (n = 9/61) of patients. In all cases, the stimulant used was methylphenidate (used for 10–12 months [n = 5], 1–4 months [n = 3], and unknown duration [n = 1]). During follow-up, stimulants were used by 10% (n = 6/61), 16% (n = 10), and 18% (n = 11) of patients in months 0–6, 0–12, and 0–24, respectively. In all cases, the stimulant used was methylphenidate. All six patients using methylphenidate in months 0–6 had used methylphenidate in the previous year. Grouping the patients according to the year of enrolment, the proportion of methylphenidate users in months 0–24 was 25% (n = 2/8), 14% (n = 3/22), 33% (n = 2/6), 17% (n = 2/12), and 15% (n = 2/13) in years 2001–2005. This proportion did not change significantly during the study (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.823). Mean age for users and nonusers of methylphenidate in months 0–24 was 10.4 and 8.6 years, respectively (mean difference, 1.9 years, 95% CI: −0.1–3.8 years; P = 0.063). In patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of ADHD (n = 41), the proportion of methylphenidate users was 15% (n = 4), 20% (n = 8), and 22% (n = 9) in months 0–6, 0–12, and 0–24, respectively.

In the first six study months, 6% (n = 3/61) of all patients had psychotherapy, occupational therapy, or play therapy; 10% (n = 6) used methylphenidate, 0% used antidepressants, and 85% (n = 52) used none of these therapies.

Outcomes

Clinical outcomes

At six-month follow-up, all clinical outcomes were significantly improved from baseline (, –). Standardized response mean effect sizes for the 0–6 month comparison were large for disease and symptom scores, medium for FBB-HKS total, inattention and hyperactivity scores, and small for FBB-HKS impulsivity score and KINDL ().

Figure 1 FBB-HKS scores.

Figure 2 Disease and symptom scores.

Figure 3 KINDL total quality of life score.

Table 3 Clinical outcomes at 0–6 months

The 0–6 month improvement of the FBB-HKS total score was analyzed in evaluable subgroups according to diagnosis, therapy, and school type (). Compared with all evaluable patients (mean improvement 0.30 points), patients with eurythmy therapy as their main therapy modality had 7% less improvement (0.30→0.28 points), patients fulfilling DSM-IV criteria for ADHD had 20% less improvement (0.30→0.24 points), and patients not using non-AM adjunctive therapies (see Methods for further description) had 17% more improvement (0.30→35 points). Among patients referred for AM art, eurythmy, or rhythmical massage therapy, the improvement was more pronounced in patients also receiving AM medical treatment, compared with patients not receiving medical treatment, but the difference was not significant (mean difference 0.10 points, 95% CI: −0.16–0.37 points; P = 0.434). Among schoolchildren, the improvement was similar in those attending Waldorf schools (0.31 points) and other schools (0.30). The 0–6 months improvement of the FBB-HKS total score showed a weak and nonsignificant positive correlation with age (Spearman-Rho =0.24, P =0.070).

Table 4 FBB-HKS total score subgroup analyses 0–6 months

At 24-month follow-up, all analyzed clinical outcomes (disease score was not documented beyond six-month follow-up) were significantly improved from baseline. Effect sizes for the 0–24 month comparison were large for FBB total and hyperactivity scores and symptom score, medium for FBB-HKS inattention score and KINDL, and small for FBB-HKS impulsivity score ().

Table 5 Clinical outcomes at 0–24 months

Other outcomes

At six-month follow-up, parents’ average therapy outcome rating (numeric rating scale from 0 “no help at all” to 10 “helped very well”) was 6.29 ± 2.70, and parent satisfaction with therapy (numeric rating scale from 0 “very dissatisfied” to 10 “very satisfied”) was 7.45 ± 2.12. The parents’ effectiveness rating of eurythmy, art, or rhythmical massage therapy was positive (“very effective” or “effective”) in 68% (n = 34/50) of evaluable patients, and negative (“less effective”, “ineffective”, or “not evaluable”) in 32% (n = 16). The physicians’ effectiveness rating was positive in 84% (49/61) and negative in 16% (n =9).

From 6- to 12-month follow-up, parent satisfaction with therapy decreased by average 1.32 points (95% CI: 0.55–2.10; P = 0.001), whereas the parents’ therapy outcome rating and the parents’ as well as the physicians’ effectiveness ratings did not change significantly.

Adverse reactions

The frequency of reported adverse drug reactions was 10% (3/31 users) for AM medications and 36% (4/11 users) for methylphenidate (P = 0.064). Adverse drug reactions of severe intensity were reported in one patient taking three different AM medications. Medication was stopped due to reported adverse reactions in two patients (AM medications, n = 1 and methylphenidate, n = 1). No adverse reactions from other medications or from nonmedication therapies occurred. No serious adverse events occurred.

Discussion

The aim of this two-year prospective cohort study was to obtain information on AM therapy for children with ADHD symptoms under routine outpatient conditions in Germany. Two-thirds of the patients engaged in eurythmy movement exercises or artistic therapies, and two-thirds used AM medications. Patients were treated largely without stimulants (82% of patients). Under AM treatment, significant and sustained improvements in ADHD symptoms and quality of life were observed. AM therapies were well tolerated.

Strengths of this study include a long follow-up period, a standardized assessment of ADHD core symptoms as well as quality of life, and high representativeness. Patients were recruited from more than half of the German federal states, 91% of those screened and eligible were enrolled, and the participating physicians and therapists resembled eligible but not participating physicians and therapists with respect to demographic characteristics. These features suggest that the study mirrors contemporary AM therapy for ADHD symptoms in outpatient settings to a high degree.

Because referral for AM treatment for ADHD symptoms is not dependent on the fulfillment of diagnostic criteria for ADHD,Citation17,Citation19 we included children with ADHD-related diagnoses and subsyndromal ADHD symptoms, as well as children fulfilling DSM-IV criteria for ADHD. The latter group was analyzed separately but had a modest sample size of 41 patients. Comparisons with other studies of DSM-IV-ADHD should therefore be interpreted with some caution. The fulfillment of ADHD diagnostic criteria was assessed by a validated checklist (DCL-HKS),Citation51,Citation52 and symptom severity was assessed with a validated questionnaire recommended for use in primary care (FBB-HKS).Citation51,Citation52 However, the physicians and parents did not receive special training in ADHD symptom rating. Also, the documentation did not include teacher ratings.

This analysis assessed AM as a whole system.Citation50 Supplementary subgroup analysis was possible for patients referred for eurythmy therapy and similar improvement was documented in this group, while the sample size of the other therapy modality subgroups (art therapy, rhythmical massage therapy, AM medical therapy) did not allow for subgroup analysis. The influence of the AM therapy modality and other therapy variables (eg, duration of the consultation with the physician at study enrolment and number of AM therapy sessions) on clinical outcomes has been assessed in multivariate analyses of children in AMOS with ADHD symptoms and other chronic indications.Citation49

Because the study had a long recruitment period, the study physicians were not able to participate throughout the period and to screen and enroll all eligible patients. For a different subset of patients from the AMOS project (patients referred to AM therapies for any chronic indication and enrolled before April 1st, 2001), it was estimated that physicians enrolled every fourth eligible patient.Citation58 This selection could bias the results if physicians were able to predict therapy response and if they preferentially screened and enrolled such patients for whom they expected a particularly favorable outcome. In this case, one would expect the degree of selection (ie, the proportion of eligible versus enrolled patients) to correlate positively with clinical outcomes, measured by the 0–12 month difference in symptom score. That was not the case, the correlation was almost zero (Spearman-Rho −0.04, P = 0.496, n = 364).Citation58 Likewise, another analysis of 500 adult patients enrolled into AMOS in the period 1999–2005 showed no correlation between the degree of selection and the 0–6 month difference in symptom score (Hamre et al submitted for publication). These analyses do not suggest that the participating physicians’ expectations of future therapy response led to any selection bias affecting clinical outcomes.

Selection bias may also occur at the level of participation versus nonparticipation of eligible physicians, in that 94% of certified AM physicians treating children with ADHD symptoms did not enroll patients into the present sample. These nonparticipating physicians resembled the participating physicians with respect to demographics. We cannot, however, exclude differences in other aspects, such as the physicians’ preferred methods for treatment of ADHD symptoms.

A limitation of the study is the absence of a comparison group receiving conventional treatment or no therapy. Accordingly, one must consider several other possible causes for the observed improvements apart from the AM treatment. In order to address possible dropout bias, missing values were replaced by the last value carried forward.Citation59 In a subgroup analysis of the FBB-HKS total score, the improvement was similar in patients not using adjunctive treatment, including stimulants. Therefore, adjunctive therapies cannot explain the improvement. Dietary modificationsCitation12,Citation60 were not documented in the study and could therefore not be evaluated. During a two-year follow-up period, as in this study, some natural or developmental recovery of ADHD symptoms may occur.Citation61 Regression to the mean due to symptom fluctuation with preferential self-selection to therapy and study inclusion at symptom peaks is another possibility. According to a previous analysis of mixed diagnoses from the AMOS project,Citation59 this phenomenon could explain up to 14% of the improvement of disease score. Other possible confounders are psychologic factors and nonspecific effects (eg, placebo effects, context effects, physician-patient interactions, patient expectations, and social desirability effects). However, because AM therapy was evaluated as a whole system, the question of specific therapy effects versus nonspecific effects was not an issue in the present analysis.

The outcome analysis of this study comprised seven clinical outcome measures, including six outcomes analyzed at two follow-up assessments, ie, a total of 13 analyses ( and ). We did not use P value adjustment for multiple testing, which is a limitation in regard to the risk of finding significant results by chance (Type I error). However, the problem of multiple testing has no universal solution, because P value adjustment will increase the risk of Type II errors.Citation55 The P values in this study indicated significant improvements, with P values ≤ 0.001 in all analyses, a constellation that would not be expected to occur by chance (eg, a Bonferroni adjustment for 13 tests would have indicated P < 0.004 as the significance level).

Apart from two studies with fiveCitation20 and 17 patients,Citation46 respectively, this study provides the first data on the treatment of ADHD symptoms in AM settings. The higher prevalence of ADHD according to DSM-IV versus ICD-10 criteria (67% versus 28% of patients), as well as the overrepresentation of boys (84%), are in accordance with the literature.Citation3,Citation8,Citation62 Mental comorbidity was less frequent in our study (17% of patients) than elsewhere (up to two-thirds),Citation8 but an underestimation in our study cannot be excluded, because the documentation did not include a structured assessment of conduct disorders, learning disorders, and tics. Forty-four percent of patients in our study were assessed in specialist practice or in outpatient clinics. Similarly, in a large German administrative database, 36% of children and adolescents with a claims diagnosis of ICD-10 F90 hyperkinetic disorder had seen a specialist at least once during the past year.Citation63 Study documentation did not include data on parental education and occupational levels, nor household income, but the proportion of privately insured patients (8%) was similar to that of the German population (10%).Citation64

Baseline severity of ADHD symptoms, assessed by the FBB-HKS total score, was two standard deviations worse than average score values in German children aged 4–17 years.Citation52 Symptom severity in our sample was higher in boys than in girls, which is similar to that in the general population.Citation52 Quality of life at baseline assessed by KINDL total score was one standard deviation worse than average score values in German children aged 3–17 years, and approximately equal to the score of children classified as abnormal according to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.Citation65 The proportion of patients treated with stimulant medication (16% of all patients and 20% of those with a DSM-IV diagnosis of ADHD in months 0–12) would seem to be lower than in Germany at the start of this study. In a large administrative dataset from the German Federal State of Hesse in year 2001, stimulants were prescribed to 25% of children aged 3–15 years with a claims diagnosis of ICD-10 F90 hyper-kinetic disorder.Citation66 This comparison should be treated with some caution, because the database analysis did not include factors influencing stimulant prescription, such as ADHD diagnostic criteria, symptom severity, and comorbidity. During the study period, the prescription of methylphenidate in Germany was almost tripled (2001→2007: 16→46 million defined daily doses),Citation67 an increase which was not reflected in our study. Possibly, families with children engaging in eurythmy or artistic exercises or other AM therapies might be less motivated to use stimulants.

In this study AM therapy was followed by improvement of ADHD symptoms and quality of life. This confirms previous findings.Citation20,Citation46 Symptom improvement in the first six months of this study, assessed by parents, amounted to one-half to two-third standard deviations for the FBB-HKS scores, which is similar to six-month results following other (non-AM) nonmedication therapies for ADHD.Citation68,Citation69 The corresponding improvement of symptom score was more pronounced, amounting to 1.3 standard deviations. Possible reasons for this discrepancy are differing scale constructions and constructs of the two instruments. The FBB-HKS (0–3 points) measures a broad range of ADHD symptoms, while symptom score (0–10 points) measures the individual symptoms deemed to be most important to each patient at baseline.

The AM approach evaluated in this study differs from many other therapies used for ADHD in two aspects. Whereas in many complementaryCitation12,Citation70,Citation71 and conventional therapies the child is essentially a passive user of products (eg, stimulants, herbs, homeopathic products or nutritional products) or recipient of treatments (eg, aromatherapy, chiropractic, or massage), the AM approach involves active as well as passive therapies. Whereas other active therapies (eg, behavioral interventions and neurofeedback) may be perceived as monotonous, the AM exercise therapies used by three-quarters of patients in this study allow for artistic movements (eurythmy) or expression (art therapy). This aspect of AM may be especially welcome in children with ADHD symptoms, many of whom are described as particularly artistic.Citation42,Citation72

Future studies of AM treatment for ADHD symptoms should include a more detailed documentation of the AM therapy modalities (eg, for eurythmy therapy, the type of exercises used and the frequency and duration of home exercises). Studies with concurrent control groups would be desirable. However, it is difficult to conduct randomized trials in AM settings, because randomization is often rejected by AM physicians and their patients, chiefly due to strong therapy preferences.Citation34,Citation35 One possible solution could be to perform a pragmatic randomized trial, recruiting patients from outside AM settings and randomizing them to immediate treatment in an AM setting or to a waiting-list control group.Citation73 Another possibility would be a nonrandomized system comparison of treatment by AM and conventional physicians with adjustment for baseline differences.Citation74 In addition, there is scope for future qualitative studies exploring the experiences of families with children with ADHD symptoms undergoing AM treatment.Citation30

Conclusion

In this study, children with ADHD and ADHD-related conditions who received AM treatment had long-term reduction of symptoms and improvement of quality of life. The improvement was similar in children not using central stimulants. Although the pre–post design of the present study does not allow for conclusions about comparative effectiveness, study findings suggest that AM therapies may be useful in the long-term care of children with ADHD symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Software-AG Stiftung and the Innungskrankenkasse Hamburg, with supplementary grants from the Christophorus-Stiftungsfonds in der GLS Treuhand e.V., the Mahle Stiftung, Wala Heilmittel GmbH, and Weleda AG. Our special thanks go to the study physicians, therapists, patients, and caregivers for participating.

Disclosure

Within the last five years HJH and GSK have received restricted research grants and CM has received lecture fees from Wala and Weleda, manufacturers of AM medications. Otherwise, all authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- BiedermanJFaraoneSVAttention-deficit hyperactivity disorderLancet2005366948123724816023516

- HöllingHErhartMRavens-SiebererUSchlackRVerhaltensauffällig-keiten bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Erste Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS) [Behavioural problems in children and adolescents. First results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschut2007505–6784793

- PolanczykGde LimaMSHortaBLBiedermanJRohdeLAThe worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysisAm J Psychiatry2007164694294817541055

- RowlandASLesesneCAAbramowitzAJThe epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A public health viewMent Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev20028316217012216060

- HarpinVAThe effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family, and community from preschool to adult lifeArch Dis Child200590Suppl 1i2i715665153

- SpencerTJADHD and comorbidity in childhoodJ Clin Psychiatry200667Suppl 8273116961427

- KeenDHadijikoumiIAttention deficit hyperactivity disorder in childrenClin Evid200815331344

- DöpfnerMFrölichJLehmkühlGHyperkinetische Störungen [Hyperkinetic Disorders]Göttingen-Bern-TorontoHogrefe-Verlag2000

- WeissMDGadowKWasdellMBEffectiveness outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Clin Psychiatr200667Suppl 83845

- SwansonJMKraemerHCHinshawSPClinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: Success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatmentJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200140216817911211365

- ConnersCKEpsteinJNMarchJSMultimodal treatment of ADHD in the MTA: An alternative outcome analysisJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200140215916711211364

- WeberWNewmarkSComplementary and alternative medical therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autismPediatr Clin North Am2007546983100618061787

- SteinerRWegmanIExtending Practical Medicine. Fundamental Principles Based on the Science of the SpiritBristolRudolf Steiner Press2000

- Derzeitige Ausbreitung der Anthroposophisch-Medizinischen Bewegung [Current Dissemination of the Anthroposophic Medical Movement]1924–2004 Sektion für Anthroposophische Medizin. Standortbestimmung/Arbeitsperspektiven. [1924–2004 Section for Anthroposophic Medicine Current status and future perspectives]DornachFree Academy of Spiritual Science2004

- CampbellDTDownward causation in hierarchically organized biological systemsAyalaFJDobzhanskyTStudies in the Philosophy of BiologyLondonMacmillan1974

- EvansMRodgerIAnthroposophical Medicine: Healing for Body, Soul and SpiritLondonThorsons1992

- SoldnerGStellmannHMAufmerksamkeitsdefizitsyndrom mit und ohne Hyperaktivität (ADHS/ADS) [Attention Deficit Syndrome With and Without Hyperactivity (ADHS/ADS)]Individuelle Pädiatrie: Leibliche, seelische und geistige Aspekte in Diagnostik und Beratung Anthroposophisch-homöopathische Therapie [Individualised Pediatrics: Somatic, psychological and spiritual aspects of diagnostics and counselling Anthroposophic-homeopathic therapy]StuttgartWissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft2007

- von ZabernBKompendium der ärztlichen Behandlung seelenpflegebedürftiger Kinder, Jugendlicher und Erwachsener. Erfahrungen und Hinweise aus der anthroposophischen Therapie [Manual of Medical Therapy for Children, Adolescents, and Adults with Disabilities. Experiences from Anthroposophic Treatment]DornachMedical Section at the Goetheanum2002

- SchmidtAMeusersMMomsenUWo ein Wille ist, aber kein Weg – Aufmerksamkeitsdefizitsyndrom mit und ohne Hyperaktivität. [Where there‘s a will but no way – Attention deficit syndrome with and without hyperactivity]Der Merkurstab2003564181195

- MajorekMTüchelmannTHeusserPTherapeutic eurythmy-movement therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A pilot studyComplement Ther Nurs Midwifery2004101465314744506

- Kirchner-BockholtMFundamental Principles of Curative EurythmyLondonTemple Lodge Press1977

- HamreHJWittCMGlockmannAZieglerRWillichSNKieneHEurythmy therapy in chronic disease: A four-year prospective cohort studyBMC Public Health200776117451596

- PützHLeitlinie zur Behandlung mit Anthroposophischer Kunsttherapie (BVAKT)® für die Fachbereiche Malerei, Musik, Plastik, Sprachgestaltung [Guideline for Treatment with Anthroposophic Art Therapy with the Therapy Modalities Painting, Music, Clay, Speech]FilderstadtBerufsverband für Anthroposophische Kunsttherapie e. V. [Association for Anthroposophic Art Therapy in Germany]2008

- PetersenPDer Therapeut als Künstler. Ein integrales Konzept von Psychotherapie und Kunsttherapie. [The Therapist as Artist. An Integrative Conception of Psychotherapy and Art Therapy]PaderbornJunfermann-Verlag1994

- TreichlerMMensch – Kunst – Therapie. Anthropologische, medizinische und therapeutische Grundlagen der Kunsttherapien [Man – Art – Therapy. Anthropological, Medical, and Therapeutic Basis for Artistic Therapies]StuttgartVerlag Urachhaus1996

- BettermannHvon BoninDFrühwirthMCysarzDMoserMEffects of speech therapy with poetry on heart rate rhythmicity and cardiorespiratory coordinationInt J Cardiol2002841778812104068

- CysarzDvon BoninDLacknerHHeusserPMoserMBettermannHOscillations of heart rate and respiration synchronize during poetry recitationAm J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol20042872H579H58715072959

- SeifertGDrieverPHPretzerKEffects of complementary eurythmy therapy on heart rate variabilityComplement Ther Med200917316116719398070

- Hauschka-StavenhagenMRhythmical Massage as Indicated by Dr Ita WegmanSpring Valley, NYMercury Press1990

- RitchieJWilkinsonJGantleyMFederGCarterYFormbyJA Model of Integrated Primary Care: Anthroposophic MedicineLondonDepartment of General Practice and Primary Care, St Bartholomew’s and the Royal London School of Medicine, Queen Mary, University of London2001

- HamreHJWittCMGlockmannAZieglerRWillichSNKieneHRhythmical massage therapy in chronic disease: A 4-year prospective cohort studyJ Altern Complement Med200713663564217718646

- Anthroposophic Pharmaceutical Codex APC, Second EditionDornachThe International Association of Anthroposophic Pharmacists IAAP2007

- WittCMBluthMAlbrechtHWeisshuhnTEBaumgartnerSWillichSNThe in vitro evidence for an effect of high homeopathic potencies – a systematic review of the literatureComplement Ther Med200715212813817544864

- KienleGSKieneHAlbonicoHUAnthroposophic Medicine: Effectiveness, Utility, Costs, SafetyStuttgartSchattauer Verlag2006

- HamreHJKieneHKienleGSClinical research in anthroposophic medicineAltern Ther Health Med2009156525519943577

- Guidelines for Good Professional Practice in Anthroposophic Medicine2003Available at: URL: http://www.ivaa.info/?p=81 Accessed Dec 11, 2009.

- Eurythmy Therapy GuidelineFilderstadtBerufsverband Heileurythmie e.V. (Eurythmy Therapy Association)2004

- List of CentersDornachCouncil for Curative Education and Social Therapy2009

- Waldorfschulen weltweitStuttgartBund der Freien Waldorfschulen2009

- SeeskariDMichelssonKArt Therapy for Children with ADHD and Associated SymptomsHelsinkiMBD-infocenter1998

- KendallTTaylorEPerezATaylorCDiagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children, young people, and adults: Summary of NICE guidanceBMJ2008337a123918815170

- ADHS bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (Aufmerksamkeits-Defizit-Hyperaktivitäts-Störung). Leitlinie der Arbeitsgemeinschaft ADHS der Kinder- und Jugendärzte e.V. [ADHD in Children and Adolescents (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). Guideline from the Work Group ADHD of Pediatricians]ForchheimArbeitsgemeinschaft ADHS der Kinder- und Jugendärzte e.V.2007

- Momsen U Leserbrief: Zum Artikel von Walter Pohl: “Das Aufmerksamkeitsdefizitsyndrom menschenkundlich betrachtet” Heft 4/2002 [Letter to the editor concerning the article by Walter Pohl “Attention deficit disorder from an anthropological viewpoint”]Der Merkurstab200356138

- von ZabernBZum Dilemma der Stimulanzienbehandlung unruhiger Kinder. [The dilemma of psychostimulants treatment in restless children]Der Merkurstab20035628487

- SoldnerGStellmannHMAufmerksamkeitsstörung mit und ohne Hyperaktivität (ADHS/ADS). [Attention deficit syndrome with and without hyperactivity (ADHS/ADS)]Der Merkurstab20045711535

- KienleGSKieneHAlbonicoHUSeeskari 1998 [Art therapy for children with ADHD and associated symptoms]Anthroposophic Medicine: Effectiveness, Utility, Costs, SafetyStuttgartSchattauer Verlag2006

- HamreHJBecker-WittCGlockmannAZieglerRWillichSNKieneHAnthroposophic therapies in chronic disease: The Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS)Eur J Med Res20049735136015337636

- FønnebøVGrimsgaardSWalachHResearching complementary and alternative treatments – the gatekeepers are not at homeBMC Med Res Methodol20077717291355

- HamreHJWittCMKienleGSAnthroposophic therapy for children with chronic disease: A two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settingsBMC Pediatr200993919545358

- BoonHMacPhersonHFleishmanSEvaluating complex health-care systems: A critique of four approachesEvid Based Complement Alternat Med20074327928517965757

- DöpfnerMLehmkuhlGDISYPS-KJ. Diagnostik-System für psychische Störungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter nach ICD-10 und DSM-IV. Manual. [DISYPS-KJ. Diagnostic Assessment System for Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents According to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. Manual]BernVerlag Hans Huber2000

- DöpfnerMGörtz-DortenALehmkuhlGDISYPS-II. Diagnostik-System für psychische Störungen nach ICD-10 und DSM-IV für Kinder und Jugendliche – II. Manual. [DISYPS-II. Diagnostic Assessment System for Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents According to ICD-10 und DSM-IV, Second Edition. Manual]BernVerlag Hans Huber2008

- WesthoffGVAS Visuelle Analog-Skalen; auch VAPS Visual Analogue Pain Scales, NRS Numerische Rating-Skalen; Mod. Kategorialskalen [VAS Visual Analogue Scales; also VAPS Visual Analogue Pain Scales, NRS Numerical Rating Scales; Mod. Categorical Scales; Mod.]Handbuch psychosozialer MessinstrumenteGöttingenHogrefe1993

- Ravens-SiebererUBullingerMKINDL® English Questionnaire for Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents Revised Version ManualBerlinRobert Koch Institute2000

- FeiseRJDo multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment?BMC Med Res Methodol20022812069695

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum1988

- McDowellIMeasuring Health A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires3rd edOxfordOxford University Press2006

- HamreHJWittCMGlockmannAZieglerRWillichSNKieneHAnthroposophic therapy for chronic depression: A four-year prospective cohort studyBMC Psychiatry200665717173663

- HamreHJGlockmannAKienleGSKieneHCombined bias suppression in single-arm therapy studiesJ Eval Clin Pract200814592392918373566

- KiddPMOmega-3 DHA and EPA for cognition, behavior, and mood: Clinical findings and structural-functional synergies with cell membrane phospholipidsAltern Med Rev200712320722718072818

- SpencerTJBiedermanJMickEAttention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiologyJ Pediatr Psychol20073266314217556405

- SchlackRHollingHKurthBMHussMDie Prävalenz der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Erste Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS)Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz2007505–682783517514469

- SchlanderMSchwarzOTrottGEViapianoMBonauerNWho cares for patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? Insights from Nordbaden (Germany) on administrative prevalence and physician involvement in health care provisionEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200716743043817468967

- Die private Krankenversicherung 2002/2003 Zahlenbericht [Financial Report for Private Healthcare Insurance 2002/2003]CologneAssociation of German Private Healthcare Insurers2003

- Ravens-SiebererUEllertUErhartMGesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Eine Normstichprobe für Deutschland aus dem Kinder- und Jugendgesund-heitssurvey (KIGGS) [Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents in Germany. Norm data from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (KiGGS)]Bundesges Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz2007505–6810818

- SchubertIKösterIAdamCIhlePDöpfnerMLehmkuhlGPsychopharmakaverordnungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Behandlungsanlass “Hyperkinetische Störung”. [Psychotropic drugs for children with the claims diagnosis “attention deficit/hyperkinetic disorder.”]Z f Gesundheitswiss2003114306324

- SchwabeUPaffrathDArzneiverordnungs-Report 2008: Aktuelle Daten, Kosten, Trends und Kommentare. [Drug Prescription Report 2008: Current data, costs, trends and comment]BerlinSpringer-Verlag2008

- AllesCKunsttherapie bei ADS. Studie zur Wirksamkeit einer trimodalen nicht-medikamentösen Therapie bei SchülerInnen zweier Sonderschulen für Erziehungshilfe. Dissertation [Art Therapy for ADD. Study of the Efficacy of a Trimodal Non-Medication Therapy For Pupils in Two Schools For Children With Educational Needs. Dissertation]CologneUniversity of Cologne2004

- DreisörnerTZur Wirksamkeit von Trainings bei Kindern mit Aufmerksamkeitsstörungen. Dissertation. [Efficacy of Training for Children with Attention Deficit Disorders. Dissertation]GöttingenGöttingen University2004

- BussingRZimaBTGaryFAGarvanCWUse of complementary and alternative medicine for symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorderPsychiatr Serv20025391096110212221307

- SinhaDEfronDComplementary and alternative medicine use in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorderJ Paediatr Child Health2005411–2232615670219

- CramondBAttention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and creativity – What is the connection?J Creat Behav1994283193210

- SteinsbekkAFonneboVLewithGBentzenNHomeopathic care for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infections in children: A pragmatic, randomised, controlled trial comparing individualised homeopathic care and waiting-list controlsComplement Ther Med200513423123816338192

- HamreHJFischerMHegerMAnthroposophic vs. conventional therapy of acute respiratory and ear infections: A prospective outcomes studyWien Klin Wochenschr20051177–825626815926617