Abstract

Aim:

Examine the effect of nursing interventions to improve vision and hearing, systematic assessment, and referral to sensory specialists on falling.

Methods:

Controlled intervention trial targeting hip fracture patients, 65 years and older, living at home and having problems seeing/reading regular print (VI) or hearing normal speech (HI). Intervention group = 200, control group = 131. The InterRAI-AcuteCare (RAI-AC) and the Combined-Serious-Sensory-Impairment interview guide (KAS-Screen) were used. Follow-up telephone calls were done every third month for one year.

Results:

Mean age was 84.2 years, 79.8% were female, and 76.7% lived alone. HI was detected in 80.7% and VI in 59.8%. Falling was more frequent among the intervention group (P = 0.003) and they also more often moved to a nursing home (P < 0.001) and were dependent walking up stairs (P = 0.003).

Conclusions:

This study could not document the effect of intervention on falling, possibly because of different base line characteristics (more females, P = 0.018, and more living alone P = 0.011 in the intervention group), differences in nursing care between subjects, and different risk factors. Interventions to improve sensory function remain important in rehabilitation, but have to be studied further.

Introduction

Vision, hearing, and combined sensory impairment are common among older peopleCitation1–Citation3 and are known risk factors for falling.Citation4,Citation5 Falling is more common with increasing age and may result in injuries, such as fractures, that cause disability, fear of falling, and reduced mobility. Thus, falling is a threat to independent and healthy living.Citation6

Some multifactorial fall-prevention studies have included analysis of interventions to improve visionCitation7–Citation9 and of recommendation for a hearing assessment.Citation10 Vision and hearing impairment are risk factors for imbalanceCitation11–Citation14 and may hinder mobility and extend the time required to regain health after illness. Although it seems obvious that improving hearing and vision would have a beneficial effect on reducing falls, the effect of such interventions in this context remains unclear.Citation15 Patients with hip fractures have a high risk for new falls and should be particular targets for fall prevention.Citation16–Citation19

Among independently living hip fracture patients, vision impairment has been found to be more frequent than in persons without hip fracturesCitation20,Citation21 In addition, visually impaired hip fracture patients have fewer optometric and ophthalmic controls.Citation22 Sensory impairment is an important risk factor for deliriumCitation23,Citation24 which is frequent in this group and associated with fallsCitation25–Citation27 and poor functional recovery.Citation28–Citation30

Unfortunately systematic evaluation of vision and hearing of elderly hospitalized patients is often neglectedCitation31,Citation32 even though most sensory problems are potentially treatable or relieved by remedies and environmental adjustments.Citation33–Citation36 Information about sensory function is important for nursing care in elderly hip fracture patients because impairments may affect recovery.Citation37 To our knowledge, there are no previous intervention studies in hip fracture patients with a major focus on improving vision and hearing function to reduce new falls.

The aim of this study was to examine, for one year after hip fracture, the effect of nursing interventions to improve vision and hearing on falling. Simple sensory tests and systematic assessment, referral to specialist services, and an educational program were included in the intervention.

Methods

Sample and measurements

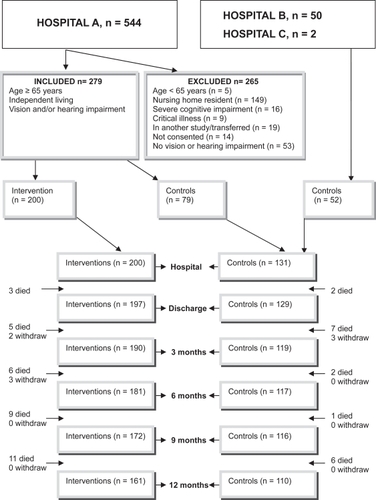

The study was performed in two orthogeriatric wards and one orthopedic unit in Norway. All patients admitted for accidental fall and hip fracture from October 2004 to July 2006 in hospital A were considered for inclusion and recruited for either the intervention group or nonintervention controls (). Patients in hospitals B and C were recruited as controls, according to the research nurse’s schedule, from July 2005 to July 2006 ().

Figure 1 Flow chart showing the number of interventions and controls at time of inclusion and follow-up periods and the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The Resident Assessment Instrument-Acute Care (InterRAI-AC)Citation38 and Combined Serious Sensory Impairment, interview guide (KAS-Screen)Citation39 were used for screening and data collection.

The KAS-Screen consists of nine domains with 110 open and standardized questions. A sample of questions about vision and hearing was applied and is described in another paper.

The InterRAI-AC is validated and tested for reliabilityCitation38 and consists of 11 domains with 62 clinical items, including socio-demographic data, physical and mental functioning, medical conditions, and services. It includes several subscales.Citation38 The Norwegian version has been translated according to accepted procedures. The Cognitive Performance ScaleCitation40,Citation41 identified cognitive impairment when the score was >0. The Delirium Score includes items concerning disorganized thinking and awareness and corresponds to the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).Citation42 Loss of Personal Activities of Daily Living (PADL)Citation43 was defined as PADL ≥ 4 (median value). Loss of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Involvement Scale, (IADL)Citation44 was defined as IADL ≥ 4 (median value). Severe painCitation45 was identified with a pain score of 3. Comorbidity was defined as having diagnoses from two or more ICD-10 classes (organ systems). Polypharmacy was defined as using six or more drugs.Citation46 A fall was defined as an unexpected event in which the person comes to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level regardless of whether an injury was sustained.Citation47 A fall injury was considered present when the incident resulted in a head injury or a fracture or wound.

Data collection procedure

Specially trained registered nurses interviewed and assessed the patients, explored the hospital records, and interviewed family and staff. The patients were assessed approximately 72 hours after surgery, and information refers to the 24-hour period preceding the assessment. Information about the patient’s condition three days prior to the fracture and the number of falls during the previous three months was obtained.

The nurses also performed the follow-up telephone calls every third month for one year with the patient or with a proxy or primary nurse if the patient was unable to give information. Reports based on the InterRAI-AC were conducted at three and twelve months. Information about falls, activity level, living arrangements, and specialist assignments was requested at each call. The number of falls was recorded up to 12 months or to death or withdrawal from the study. The date of the first fall was set to 28 days before the telephone interview because the majority of the patients were unable to recall the exact date.

The hospital administration system was used to record readmissions to the hospital through the follow-up year. Reports from specialist services were also examined.

Screening

Sensory function was assessed with a hearing aid or glasses if normally used and available. Hearing impairment was categorized as mild (required quiet surroundings to hear well), moderate (a person talking must speak loudly, clearly, and precisely), or severe (extremely reduced hearing to no useable hearing) (score 1–3). Vision impairment was categorized as mild (reads large letters but not normal type sizes in newspapers), moderate (unable to read newspaper headlines, but recognizes objects), or severe (can only see light, colors, or contours to no vision) (score 1–3). Combined sensory loss was present with impairment in both vision and hearing. Patients who scored 0 (no impairment) on InterRAI-AC but reported vision and/or hearing to be fair to very poor (KAS-Screen) were classified as having impairment.

Intervention

The intervention was multifactorial and aimed at improving hearing and vision. Objective sensory tests were performed on those who scored positive and were candidates for intervention. A nurse (EVG) carried out vision examinations at the bedside. Donders’ confrontation method, the Amsler grid testCitation1 and Titmus Fly StereotestCitation48 gave information about, respectively, peripheral vision field, central field vision, and stereo depth perception. Visual acuity was measured by the Snellen method at a 3-m distance with glasses if normally used and available and was categorized according to the measurement on the better eye. An audiologist performed the hearing examination. Audiometric thresholds were established for frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz and categorized by pure-tone average threshold on the better ear.

Ears were inspected with othoscopy and earwax removed.Citation49,Citation50 Hearing aid batteries, tubes, and filter were replaced when needed and service appointments organized. Glasses were cleaned daily during the hospital stay.

A pamphlet with information and individual education about vision and hearing, based on the work by Kee, Houde, and Tolson,Citation51–Citation53 was given to each patient. The educational method was dialogue, a conversation between equal partners aimed to obtain insight and understanding of sensory impairment and reveal coping strategies that the patient could apply to optimize vision and hearing.Citation54 The educational session was timed to accommodate the patient’s preference and treatment schedule. Patients were referred to a community occupational therapist when sensory remedies were needed.

Patients were offered an appointment with an ear-nose-throat (ENT) specialist or an audiologist when pure-tone audiometry (PTA) detected hearing thresholds of ≥35 dB, if hearing was reported to be fair to poor (KAS-Screen), or if they had mild to severe hearing impairment (RAI-AC).Citation55,Citation56 The patients were also offered an appointment at an eye clinic (ophthalmologist and optometrist) when visual acuity (VA) < 0.8, they failed the Donders test, Amsler grid, or Titmus Fly Stereotest, they reported vision to be fair to poor (KAS-Screen), or had mild to severe vision impairment (RAI-AC).Citation22 Patients with regular visits to specialists were asked to bring a letter about the study at next consultation. To avoid long waiting lists for specialist assessments, arrangements were made with an eye clinic and a hearing clinic (ENT specialist and audiologists). Twenty-six patients were offered a home visit by an audiologist/audio pedagogue to help with hearing aids and communication skills.Citation57

During the follow-up period, patients, relatives, and community staff received reminders about appointments with specialists and measures to improve sensory functions.

Statistical analyses

Based on the estimate from Shumway-Cook,Citation18 we calculated that we should include 400 patients to obtain a power of 80% to detect a 15% reduction in falls (controls, 50% falls; interventions, 35% falls) with a significance level of 5%. However, because of resource limitations, the final sample size was 331. The power was reduced by 1%.

Baseline and outcome data are presented as frequencies for categorical variables and mean values with standard deviation or median with interquartile range, when appropriate, for continuous variables. Differences between the intervention and control groups were tested using Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical variables; for continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney test or t-tests were used when appropriate. Odds ratios (ORs) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for outcome variables.

The association between intervention and survival rate (time to first fall) was assessed using a Cox proportional hazard model. Survival curves are presented graphically, controlled for age, gender, delirium, and urine incontinence. Dual sensory loss, new glasses/remedies, new/adjusted hearing aids, climbing stairs, feeling discouraged, nursing home residence, and living alone were excluded from the model one at a time in a step-down fashion. Likewise, any association between sensory treatment and survival rate (time to first fall) was assessed using the Cox proportional hazard model. The following variables were excluded from the Cox proportional hazards model: dual sensory loss, climbing stairs, feeling discouraged, nursing home residence, and living alone.

All analyses were by intention-to-treat, using a last-value-carried-forward strategy. The Statistical Package for Social SciencesCitation58 was used for the statistical analyses and prepared as described in Peat and Barton.Citation59 The level of significance was set to 0.05 (5%).

Ethics

We had initially planned to do a controlled study by recruiting participants for intervention and control, respectively, every other month. The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics did not approve this design because support for improved sensory functions then would have been given to some patients but not to others in the same ward and possibly at same time. The study was approved when intervention participants were recruited first and control participants later. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and their relatives were informed.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age was 84.2 years, 79.8% were female, and 76.7% lived alone. The intervention group and the control group differed in several variables, including gender and living alone ().

Table 1 Characteristics of participants at baseline given as number of cases (%), unless otherwise stated, with P values for group differences

Vision impairment alone was detected in 19.3%, hearing impairment alone in 40.2%, and 40.5% had combined sensory impairment. Vision impairment (P = 0.008) and dual sensory impairment (P = 0.006) were detected more often among the controls ().

For visual function, 32.6% of the patients had mild, 13.0% moderate, and 7.8% severe impairment. The controls more often had mild or moderate impairment (P = 0.001), as assessed using RAI-AC. Eighteen percent of the patients had two or more eye diagnoses. Fifty percent with cataract had not had surgery, and the proportion was higher in the intervention group (P = 0.002) ().

Table 2 Self-reported characteristics of participants at baseline given as number of cases (%), unless otherwise stated, with P values for group differences

The severity of hearing impairment was similar between the two groups: 49.5% with mild, 27.8% with moderate, and only four patients (1.2%) with severe loss, who were practically deaf, as assessed using RAI-AC. Eleven percent had problems related to acoustic trauma, diseases, congenital factors, or ototoxic medication (). Earwax was removed in 29.5% of the patients during the initial hospital stay.

Results from the pure-tone audiometry and visual acuity assessments (n = 186) is described in another paper.

Specialist assignments

On their own initiative some participants in the control group contacted specialists to take care of their vision and hearing impairment during the follow-up year (36.6% and 10.7%, respectively). As for the intervention group, 46.0% visited specialists for their vision and 36% for hearing impairments (). Both groups received little help in the first three months after discharge but specialist intervention frequencies increased as the year progressed. Of the 78 persons in the intervention group who did not see a vision specialist as recommended, 64% were too ill, 24% did not want to, were tired, or had no one to accompany them, 12% provided no explanation. Of the 99 intervention patients who did not visit a hearing specialist as recommended, 39% were too ill, 47% replied that it was unnecessary or that they were too tired or had no one to accompany them, and 13% provided no explicit reason.

Table 3 Outcomes given as number of cases (%), unless otherwise stated, with odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) and P values for group differences

Falls

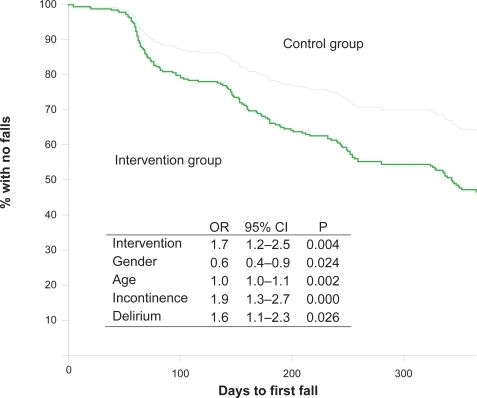

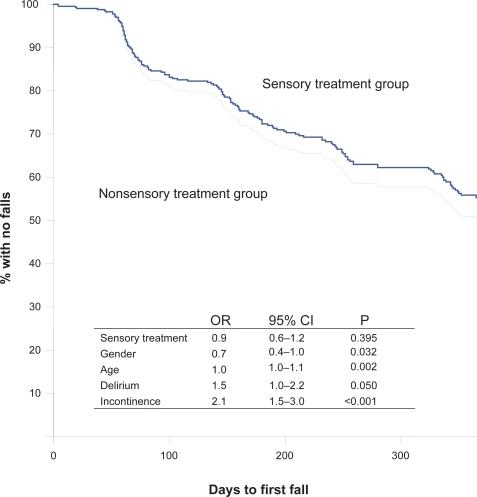

Cox proportional hazard model shows the association between intervention and survival rate (time to first fall) in curves controlled for age, gender, delirium, and urine incontinence (p = 0.004) (). During the follow-up, falls were more frequent in the intervention group than in the control group (, ), but there was no difference in falls causing injuries between the groups (). Totally 117 (35.3%) of all the subjects included in the study received treatment by hearing and/or vision specialists during the follow up year. Any association between the sensory treatment and survival rate (time to first fall) was likewise shown using the Cox proportional hazard model. There were no differences in falls between participants provided with sensory treatment/new sensory remedies and those without, independently of group assignment (p = 0.395) (). In analysis of subgroups of controls from hospitals B and C and the intervention group, there was no difference in falls. However, between the control group from hospital A and the intervention group (from the same hospital), there was a difference in falling (P < 0.0001), in falling twice or more (P = 0.003), and in the number of falls (P < 0.0001, SE difference 0.3, 95% CI, 1.7–0.5).

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier curves presenting time to first fall for the intervention group (n = 200 participants) versus the control group (n = 131 participants) controlled for by age, gender, delirium, and urine incontinence.

Figure 3 Kaplan–Meier curves presenting time to first fall of persons who received sensory treatment versus persons who did not, controlled for by age, gender, delirium, and urine incontinence. Sensory treatment group, n = 117; nonsensory treatment group, n = 214.

Most falls (65.1%) happened during daytime in both groups. Patients in the intervention group fell more often because of “the legs giving away” (P < 0.0001). For other explanations of falls (stumbled, got stuck and slipped), there were no differences.

Discussion

Disappointingly, this intervention did not reduce the number of falls in the first year after a hip fracture. There was even an increase in falls in the intervention group compared to the controls in hospital A. However, the frequency of injuries from falls was the same between the intervention group and control group.

There are many possible explanations for these findings. Other health and functional problems may have dominated and hidden the possible positive effect of the intervention. Muscle weakness, diabetic polyneuropathy, or cerebral- and cardiovascular diseases are common in this patient group and are well-known risk factors for falls.Citation5,Citation60,Citation61

Although the nurse-patient dialogues were timed according to the patients’ preference during the hospital stay, some patients were may not have been ready for this kind of conversation so early in the recovery process. The hip fracture, rehabilitation, pain, and discouragement might have dominated their focus of attention. The written information and quarterly telephone calls was intended to strengthen the patients’ and relatives’ understanding and reflection about actions to take to maximize vision and hearing function. However, these measures might not have been sufficient for patients to actually carry out necessary actions.

Furthermore, adjustment to new glasses, hearing aids, and other remedies might be difficult at a time of increased vulnerability. Additionally, medical treatment such as surgery and medication might have had adverse affects, including dizziness and reduced sensory function. This may have contributed to more falls, particularly shortly after treatment initiation. Another explanation could be that people who have begun a special intervention to improve vision and hearing are more active and have an increased risk for falling. However, lack of physical activity is probably a greater threat to this patient group.Citation62

Differences between the intervention participants and the control group may explain the lack of effect of our intervention. Baseline data showed that more patients in the intervention group suffered from urine incontinence, were female, were living alone, and were discouraged (); all are risk factors for falling.Citation5,Citation63 In the follow-up period, more intervention participants resided in a nursing home and needed assistance when climbing stairs. The prevalence of falling is higher in nursing homes Citation64,Citation65 and among elderly with difficulties in climbing stairs.Citation66 Being female and suffering from urinary incontinence were significant factors in a Cox regression model of falls in the current study. Delirium was a more common complication during the hospital stay among the control participants and is believed to increase the risk of falls. However, this effect might have interacted with the other factors.

Patients and their relatives recorded falls when the patients lived at home, while nursing staff recorded falls in nursing homes. Documentation of falls is a standard procedure in nursing homes in this city and might thus be more accurate than documentation of at home falls. Reporting of falls that involved injuries is probably more accurate than falls without injuries. There were no differences in falls causing injuries between the intervention and control groups.

The unexpected result may also have been biased by the fact that the patients were aware of whether they received interventions or not.Citation67 The nurses who performed the interviews were not blinded to the groups and might also have influenced the results. Usually such factors will result in a bias towards a positive effect for the intervention group.Citation68

The participants were not randomly selected for assignment to intervention or control. The intervention participants were included first, in a newly established orthogeriatric unit. During the study period, the routines and quality of care in the unit probably improved. The control participants were included later from this hospital (A) with more experienced staff and improved routines. Most likely the staff in hospital B had also gained high competence in the geriatric field. The orthogeriatric units were established at the same time. Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), in combination with a prevention program,Citation69 is a cornerstone in an orthogeriatric unit,Citation70,Citation71 and implementation is believed to take some time. Follow-up routines by a physiotherapist after three months were established in hospital A during the study period and might also have prevented falls in the control group.

It is not known whether the increased number of falls in the intervention group might have been even higher without the intervention, as indicated by Davison and colleagues.Citation17 It is also possible that an intervention effect is delayed and might have manifested after a follow-up period. Consultations by specialists took place during the whole year and could support this explanation. It is also well known that it takes time to accept the idea that a hearing aid is necessary.Citation72

The awareness of sensory impairment and need for intervention was communicated to the nursing staff during the intervention period. An improved attitude to vision and hearing improvement might therefore have been included in the daily nursing care of control patients. The number of control participants provided with visual treatment and remedies during the follow-up period supports this explanation. In addition, communication with the nurses in the follow-up interviews might have inspired control participants to see a specialist. In the analysis of patient subgroups according to “provided treatment/new sensory remedies” and “no treatment/no new sensory remedies,” there was no difference in falls. The same result emerged between subgroups of controls from hospitals B and C and the intervention group. However, the control group in hospital A had less falls in the follow up year compared to the intervention group, most likely because of improved treatment and rehabilitation, better nursing care and the introduction of CGA and a fall prevention program. Fewer patients in the control group (Hospital A) felt discouraged and suffered from urine incontinence during the hospital stay, factors associated with increased risk of falling.Citation5

The most likely explanations for the lack of effect of our intervention are different baseline characteristics, improvement of care from the time of inclusion of intervention participants to inclusion of controls, and differences in other health and functional problems that might have contributed to the risk of falling.

Another limitation of the study is that some patients with vision problems might not have been included because of shortcomings of the screening procedure; loss of peripheral visual fields, depth perception, and distance visual acuity were not tested in the screening procedure, and self report and a reading test would not be able to unmask such problems in every patient. We believe that the methods for detecting hearing impairment were better, although some patients reported “no hearing problem” yet were unable to hear normal speech. This discrepancy might be the result of a gradual adjustment to withdrawal from social contact.

A final limitation was that we did not receive specialist reports for the control patients and for patients with specialist contacts established prior to this study, but relied on the patient’s own information about the consultations.

Conclusions

Vision, hearing, and combined impairments are very common in hip fracture patients, but this study could not document the effect of hearing and vision interventions conducted by nurses on improving falling frequency.

Nevertheless, in nursing care for hip fracture patients, we believe that detection of vision and hearing impairment and interventions to improve such functions are important not only to prevent future falls, but also for the rehabilitation process.

It is a challenge to design future studies to explore the effect of vision and hearing intervention on falling in this patient group. Other treatment and care must be similar, and for ethical reasons, patients with and without intervention must not be mixed. The best way to achieve appropriate data is probably to screen and randomize patients as soon as possible after surgery and then to transfer them to two different units that are as similar as possible in all variables except for the intervention. An alternative is to include and randomize all patients without screening because vision and hearing impairment is so common among hip fracture patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Haegerstrom-PortnoyGThe GlennAFry Award Lecture 2003Vision in elders – summary of findings of the SKI studyOptom Vis Sci200582879315711455

- BorchgrevinkHMTambsKHoffmanHJThe Nord-Trondelag Norway Audiometric Survey 1996–98: unscreened thresholds and prevalence of hearing impairment for adults >20 yearsNoise Health2005711516417702

- BrennanMBallySJPsychosocial adaptations to dual sensory loss in middle and late adulthoodTrends Amplif20071128130018003870

- CrewsJECampbellVAVision impairment and hearing loss among community-dwelling older Americans: implications for health and functioningAm J Public Health200494823915117707

- TinettiMEInouyeSKGillTMShared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromesJAMA19952731348537715059

- InouyeSKStudenskiSTinettiMEGeriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric conceptJ Am Geriatr Soc2007557809117493201

- CloseJEllisMHooperRPrevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trialLancet199935393710023893

- DayLFildesBGordonIRandomised factorial trial of falls prevention among older people living in their own homesBMJ200232512812130606

- ClemsonLCummingRGKendigHThe effectiveness of a community-based program for reducing the incidence of falls in the elderly: a randomized trialJ Am Geriatr Soc20045214879415341550

- CasteelCPeek-AsaCLacsamanaCEvaluation of a falls prevention program for independent elderlyAm J Health Behav200428Suppl 1S516015055571

- GersonLWJarjouraDMcCordGRisk of imbalance in elderly people with impaired hearing or visionAge Ageing1989183142711920

- TinettiMEWilliamsCSGillTMDizziness among older adults: a possible geriatric syndromeAnn Intern Med20001323374410691583

- ChoyNLBrauerSNitzJChanges in postural stability in women aged 20 to 80 yearsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2003585253012807923

- StevensKNLangIAGuralnikJMEpidemiology of balance and dizziness in a national population: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of AgeingAge Ageing200837300518270246

- GillespieLDGillespieWJRobertsonMCInterventions for preventing falls in elderly peopleCochrane Database Syst Rev20034CD00034014583918

- TinettiMEClinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly personsN Engl J Med200334842912510042

- DavisonJBondJDawsonPPatients with recurrent falls attending Accident and Emergency benefit from multifactorial intervention – a randomised controlled trialAge Ageing200534162815716246

- Shumway-CookACiolMAGruberWIncidence of and risk factors for falls following hip fracture in community-dwelling older adultsPhys Ther2005856485515982171

- GarciaRLemeMDGarcez-LemeLEEvolution of Brazilian elderly with hip fracture secondary to a fallClinics2006615394417187090

- AbdelhafizAHAustinCAVisual factors should be assessed in older people presenting with falls or hip fractureAge Ageing200332263012540344

- SquirrellDMKennyJMawerNScreening for visual impairment in elderly patients with hip fracture: validating a simple bedside testEye20051955915184957

- CoxABlaikieAMacewenCJOptometric and ophthalmic contact in elderly hip fracture patients with visual impairmentOphthalmic Physiol Opt2005253576215953121

- EdlundALundstromMKarlssonSDelirium in older patients admitted to general internal medicineJ Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol200619839016690993

- InouyeSKZhangYJonesRNRisk factors for delirium at discharge: development and validation of a predictive modelArch Intern Med200716714061317620535

- MasudTMorrisROEpidemiology of fallsAge Ageing200130Suppl 43711769786

- VassalloMSharmaJCAllenSCCharacteristics of single fallers and recurrent fallers among hospital in-patientsGerontology2002481475011961367

- VassalloMSharmaJCBriggsRSCharacteristics of early fallers on elderly patient rehabilitation wardsAge Ageing2003323384212720623

- DolanMMHawkesWGZimmermanSIDelirium on hospital admission in aged hip fracture patients: prediction of mortality and 2-year functional outcomesJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200055M5273410995051

- MarcantonioERFlackerJMMichaelsMDelirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fractureJ Am Geriatr Soc2000486182410855596

- OlofssonBLundstromMBorssenBDelirium is associated with poor rehabilitation outcome in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fracturesScand J Caring Sci2005191192715877637

- JackCISmithTNeohCPrevalence of low vision in elderly patients admitted to an acute geriatric unit in Liverpool: elderly people who fall are more likely to have low visionGerontology19954128058537012

- LimJKYapKBScreening for hearing impairment in hospitalised elderlyAnn Acad Med Singapore2000292374110895346

- LichtensteinMJHearing and visual impairmentsClin Geriatr Med19928173821576574

- NottleHRMcCartyCAHassellJBDetection of vision impairment in people admitted to aged care assessment centresClin Experiment Ophthalmol200028162410981787

- ErberNPUse of hearing aids by older people: influence of non-auditory factors (vision, manual dexterity)Int J Audiol200342Suppl 22S21512918625

- RosenbergEASperazzaLCThe visually impaired patientAm Fam Physician2008771431618533377

- LiebermanDFrigerMVisual and hearing impairment in elderly patients hospitalized for rehabilitation following hip fractureJ Rehabil Res Dev2004416697415558396

- GrayLCBernabeiRBergKStandardizing assessment of elderly people in acute care: the interRAI Acute Care InstrumentJ Am Geriatr Soc2008565364118179498

- LyngKSvingenEMIdentifying severe dual sensory loss in old age: evaluation of a screening method based on a checklist of issuesOsloNova2001

- MorrisJNFriesBEMehrDRMDS Cognitive Performance ScaleJ Gerontol199449M174828014392

- HartmaierSLSloanePDGuessHAValidation of the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale: agreement with the Mini-Mental State ExaminationJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci199550M128337874589

- InouyeSKvan DyckCHAlessiCAClarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of deliriumAnn Intern Med199011394182240918

- MorrisJNFriesBEMorrisSAScaling ADLs within the MDSJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci199954M5465310619316

- LandiFTuaEOnderGMinimum data set for home care: a valid instrument to assess frail older people living in the communityMed Care20003811849011186297

- FriesBESimonSEMorrisJNPain in US nursing homes: validating a pain scale for the minimum data setGerontologist200141173911327482

- FialovaDTopinkovaEGambassiGPotentially inappropriate medication use among elderly home care patients in EuropeJAMA200529313485815769968

- LambSEJorstad-SteinECHauerKDevelopment of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensusJ Am Geriatr Soc20055316182216137297

- HascheHGockelnRde DeckerW[The Titmus Fly Test – evaluation of subjective depth perception with a simple finger pointing trial. Clinical study of 73 patients and probands]Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd2001218384311225399

- Lewis-CullinanCJankenJKEffect of cerumen removal on the hearing ability of geriatric patientsJ Adv Nurs1990155946002358577

- McCarterDFCourtneyAUPollartSMCerumen impactionAm Fam Physician2007751523817555144

- KeeCCMillerVPerioperative care of the older adult with auditory and visual changesAORN J199970101216 quiz 1020:1022–14.10635425

- TolsonDNolanMGerontological nursing. 4: Age-related hearing exploredBr J Nurs22420009205811033636

- HoudeSCHuffMHAge-related vision loss in older adults. A challenge for gerontological nursesJ Gerontol Nurs200329253312710356

- HageAMLorensenMA philosophical analysis of the concept empowerment; the fundament of an education-programme to the frail elderlyNurs Philos200562354616135215

- PopelkaMMCruickshanksKJWileyTLLow prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults with hearing loss: the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc199846107589736098

- SmeethLFletcherAENgESReduced hearing, ownership, and use of hearing aids in elderly people in the UK – the MRC Trial of the Assessment and Management of Older People in the Community: a cross-sectional surveyLancet200235914667011988245

- HeineCBrowningCJCommunication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in older adults: overview and rehabilitation directionsDisabil Rehabil200224763312437862

- SPSSBase 100 User’s guideChicagoMarketing Department SPSS Inc1999

- PeatJBartonBMedical statistics: a guide to data analysis and critical appraisalMaldenBlackwell2005

- GanzDABaoYShekellePGWill my patient fall?JAMA2007297778617200478

- StevensJAOlsonSReducing falls and resulting hip fractures among older womenMMWR Recomm Rep200049RR-231215580729

- StenvallMElingeEvon Heideken WagertPHaving had a hip fracture – association with dependency among the oldest oldAge Ageing200534294715863415

- KharichaKIliffeSHarariDHealth risk appraisal in older people 1: are older people living alone an “at-risk” group?Br J Gen Pract200757271617394729

- RubensteinLZJosephsonKRRobbinsASFalls in the nursing homeAnn Intern Med1994121442518053619

- FonadEWahlinTBWinbladBFalls and fall risk among nursing home residentsJ Clin Nurs2008171263418088264

- BerglandAJarnloGBWyllerTBSelf-reported walking, balance testing and risk of fall among the elderlyTidsskr Nor Laegeforen2006126176816415942

- MackenzieLBylesJD’EsteCValidation of self-reported fall events in intervention studiesClin Rehabil200620331916719031

- AltmanDPractical statistics for medical research1st edLondonChapman and Hall1991

- StenvallMOlofssonBLundstromMA multidisciplinary, multifactorial intervention program reduces postoperative falls and injuries after femoral neck fractureOsteoporos Int2007181677517061151

- Antonelli IncalziRGemmaACapparellaOOrthogeriatric Unit: a thinking process and a working modelAging Clin Exp Res2008201091218431077

- PioliGGiustiABaroneAOrthogeriatric care for the elderly with hip fractures: where are we?Aging Clin Exp Res2008201132218431078

- GusseklooJde BontLEvon FaberMAuditory rehabilitation of older people from the general population – the Leiden 85-plus studyBr J Gen Pract2003535364014694666