Abstract

Aim:

With the overall objective to develop future strategies for a more health-promoting health service in Sweden, the aim of this paper was to describe how health personnel view barriers and possibilities for having a health-promoting role in practice.

Materials and methods:

Seven focus group discussions were carried out with a total of 34 informants from both hospital and primary health care settings in Sweden. The informants represented seven professional groups; counselors, occupational therapists, assistant nurses, midwives, nurses, physicians, and physiotherapists. The data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results:

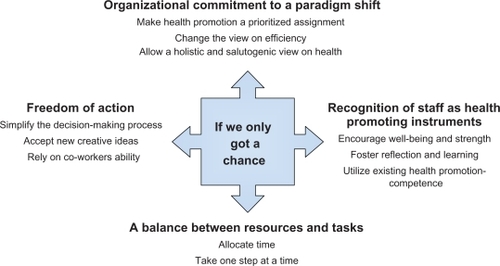

The analysis resulted in one major theme “If we only got a chance”. The theme captures the health professionals’ positive view about, and their willingness to, develop a health-promoting and/or preventive role, while at the same time feeling limited by existing values, structures, and resources. The four categories, “organizational commitment to a paradigm shift”, “recognition of staff as health-promoting instruments”, “a balance between resources and tasks”, and “freedom of action” capture what is needed for implementing and increasing health promotion and preventive efforts in the health services.

Conclusions:

The study indicates that an organizational setting that support health promotion is still to be developed. There is a need for a more explicit leadership with a clear direction towards the goal of “a more health–promoting health service” and with enough resources for achieving this goal.

Introduction

The Ottawa Charter has been guiding the goals and concepts of health promotion during the past 20 years and has thus been a part of shaping a global public health practice.Citation1 One of the five actions identified was re-orienting health services towards a better balance between health promotion, disease prevention and treatment, and to include a focus on population health outcomes alongside individual health outcomes. However, it seems that this strategy has been the least systematically implemented. Across the world, the role and structure of health systems continues to be dominated by the provision of care for acute and chronic conditions.Citation2

The principles and concepts of the Ottawa Charter are reflected in the new Swedish national public health strategy, adopted by the Parliament (Riksdag) in 2003 and updated in 2008.Citation3,Citation4 One of the 11 objectives focuses on “A more health-promoting health service” and underlines that health services need to be more health-oriented. This implies a shift in perspective towards a holistic view of people’s health and a transition to a more health-promoting and preventive service.

The adoption of the Swedish public health policy was not linked to an increase in monetary resources.Citation5 A rough estimate is that only 5% of the total health and medical care costs are spent on preventive measures.Citation6 As a consequence of a growing gap between demands and resources, health services today are becoming more and more overloaded. Transferring patient care from the hospitals to primary care creates greater difficulties for those services to carry out active public health work. Disease-oriented assignments have received greater funding whereas preventative measures have been cut down.Citation7

The health service is a complex organization with several important factors affecting its ability to live up to goals and assignments. Apart from the resources invested into health promotion, the structure and modes of working are likely to influence the possibilities for a preventive and health promotion orientation.Citation6

According to Kouzes and Mico, the organization is comprised of three distinct and conflicting domains; policy, management, and service domains.Citation8 Each domain operates by principles, norms, success measures, structural arrangements, and work modes which are incongruent with the others and inhibits the development of a common vision of the organization.Citation8 The service domain in turns consists of several professional groups that may have different sets of values, aims, and demands specific to their own interests.

This paper focuses on the service domain since health professionals play a key role in implementing the goal of “a more health-promoting health service”. Consequently, their approach to, and knowledge about, health promotion will greatly influence how the goal will be applied in the future.

This study is part of a larger project with the objective to develop future strategies for a more health-promoting health service. The aim of this substudy is to describe how health care professionals view barriers and possibilities for having a health-promoting role in practice.

Material and method

The study had a qualitative research design. Focus group discussions were chosen for data collection since they allow utilization of the group dynamic and are well suited for exploring people’s views and experiences of concrete phenomena as well as of more abstract concepts.Citation9

Study setting

The study was performed in the county of Västerbotten, located in northern Sweden. The county council administers three hospitals and 35 community health care centers.

Sampling of informants

The health professionals were regarded as a “group” since the aim was to capture the range of experiences and views among them. In the purposive sampling, efforts were made to include men and women from different professional groups and health care settings; the actual selection was facilitated by three key persons working at the county council administration. In collaboration with the research group, they suggested participants to invite and contacted them by mail.

Data collection

In total, seven focus groups were organized, with a total of 34 informants, of which nine were men. The professional groups were represented by one counselor, two occupational therapists, two physiotherapists, four assistant nurses, five midwives, 10 nurses, and 10 physicians. The participants working experiences included primary health care (including child health services, maternal health care and home nursing) and different hospital settings; dementia care, emergency care, gynecology and obstetrics, intensive care, medicine, orthopedics, palliative care, psychiatry, rehabilitation and surgery. The groups varied from four to six participants, with five groups being homogeneous and two mixed in terms of profession. The homogeneous consisted of midwifes (one group), nurses (two groups), and physicians (two groups) whereas the remaining mixed groups included informants from the other professions. The discussions were conducted in settings situated within the three hospital premises and lasted approximately two hours. In order to obtain a relaxed and comfortable atmosphere, a joint lunch was arranged before initiation of the data collection, where the participants were given an opportunity to introduce themselves for each other. Three members of the research team took turns in being the “moderator” and the assisting observer/recorder. A thematic guide was used focusing on five themes; the concept of health, the concept of health promotion, health promotion in practice, health-promoting leadership and health-promoting workplace. To facilitate the discussion the participants were asked individually to write down three wishes for future health-promoting health services before reflecting about their thoughts together as a group. This paper is based on the theme “health promotion in practice”. Barriers for having a health-promoting role were not specifically asked for, but spontaneously articulated and probed when discussing the subthemes; the meaning of health-promoting services, working with health promotion, developing the health-promoting role, and desires for the future.

Data analysis

The focus group discussions were taped and transcribed verbatim. The transcriptions were read through several times for familiarization with the material and to obtain a sense of the whole. Statements dealing with factors influencing the professional’s role for health promotion were identified and analyzed using an inductive approach of qualitative content analysis.Citation10,Citation11 Words and sentences containing aspects related to each other were labeled with codes close to the text. Codes with similar content were then developed into subcategories and categories. Finally, a theme based on the text as a whole was formulated. Throughout the analysis process, the whole research group was involved in reading and interpreting the material. The actual coding was performed by the first author (HJ), but discussed in “peer-debriefing” sessions to enhance the trustworthiness of the research findings.

Ethical considerations

The aim of the research project together with the focus group methodology was described to the participants in an invitation letter. Permission to take part in the study without deduction from salary was granted by the employer but no other incentive was offered. They were all informed that the participation was voluntary and that confidentiality would be secure throughout the research process. Prior to the discussions the participants were reminded about the confidentiality issue and encouraged to agree that the views shared would remain with the group. The study was approved by local Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Umeå University (Um dnr 03-133).

Results

The analysis resulted in one major theme “If we only got a chance” capturing the health professionals’ positive view about health promotion and/or disease preventionFootnotea being an important aspect of their professional role. They described health-promoting work as enjoyable, stimulating and meaningful, bringing benefits both to themselves and to the patients. However, they also believed that the health service has a health-promoting potential that is not optimally utilized. They often felt frustrated and restricted, realizing the great demands of health-promoting activities and how cost-effective it would be, both from a health services and a societal perspective. Their written wishes for future health promotion services clearly indicated a need for change at different levels in the health system.

summarizes the main finding, and also illustrates the categories (bold) and the subcategories (normal) that capture what is needed for implementing and increasing health promotion and preventive efforts in the health service. The result presentations follow these headings and direct quotations from the discussions are included to indicate how the interpretation is grounded in the data.

Organizational commitment to a paradigm shift

The health professionals argued that a more health-promoting health service implies completely new ways of thinking and working. It calls for great changes; a paradigm shift. This holds for all parts and levels of the organization.

Make health promotion a prioritized assignment

It was obvious that the health professionals were holding the health care management responsible for creating legitimacy and for prioritizing health promotion. They wanted directional signals from the “decision-makers” to pave the way and show that they take health promotion seriously.

Then we have to have the possibility to work in such a way that we wish to work, out towards the population, more groups, we try as well as we can but despite everything they stand there and have to have the traditional health care also, that is a thing for those who lead this “monstrosity” to turn this vessel a little bit.

The informants were unable to identify that leadership had prioritized preventive and health-promoting efforts.

From the leadership side one has the expectation that health care must fix everything that is scientifically proven ... and that means that one places all one’s energy on increasing our health-caring ability, one places all energy there and does not create space, does not assign resources in order to work in a health-promoting manner.

Change the view on efficiency

Health promotion efforts were not only viewed as specific, planned and measurable activities but also as natural elements integrated into daily work and as an attitudinal approach in meeting with patients. What happens in the interaction between a care-provider and a care-seeker might be hard to measure and value. Health-promoting efforts were also generally associated with higher quality of care and engagement; and engagement was perceived as time-consuming. The productivity thinking where the efficiency is measured by quantity was therefore regarded a barrier to a health promotion approach.

No one has even tried to measure what we do; rather, we are still stuck in the 30- to 40-year-old system where we measure the quantity of efficiency.

Allow a holistic and salutogenic view on health

The health professionals stressed that a health-promoting perspective implies a comprehensive view on human life where the individual has to be considered as a whole. This type of holistic approach was seen as being restricted by a strained economic situation where cost has precedence over patient concerns. The health care’s long tradition of troubleshooting with demands for diagnosing and confirming illness for sick leave purposes was also seen as posing a barrier to a more salutogenic approach.

Therefore, this sabotages our possibility to be salutogenic because we must concentrate on truly finding a diagnosis that can be written on the certificate.

Accordingly, a health-promoting perspective claims a shift from costs to human concerns as well as a shift from focusing on problems and risk factors to seeing possibilities, resources and factors that keep people healthy.

A holistic view where health promotion is the focus, of course, puts new demands on the staff. Our informants saw the need for acknowledging new professional groups both within and outside the health services.

Recognition of staff as health-promoting instruments

Promoting health in others was described as an “advanced task” and the health professionals regarded themselves as their most important working tool.

Encourage well-being and strength

The health professionals indicated that they used themselves as instruments to promote health in others which required a sense of well-being and strength; they had to feel “at their best” to be able to perform well.

When it pertains to health-promoting health care, I can’t refrain from highlighting the health of staff. It is, despite everything, ourselves we use as instruments so that our patients will feel better. And if the staffs are overcome with stress, heavy workload, too great demands, and an unclear organization, then we are not good staff. All the techniques that we use are essentially bullshit because the important thing is what we give of ourselves, and if one doesn’t feel well oneself, is too stressed, and feels poorly, then one is not a good health care professional. That’s just the way it is.

A positive attitude among the personnel was also seen as indirectly promoting the health of the patients. Personnel having a good time and laughing at work were seen to transmit positive energy to the patients.

We had a patient who was in a four-person room ... this is what she said when I brought the lunch ... “it is so fun to hear how you sit and laugh in the staff room when you have coffee in the morning, because everyone laughs so heartily”, and she means that she feels that she becomes alert when she heard how we sat and laughed and had fun at work.

The health professionals gave several examples of the negative health impact of their own working environment. They criticized the management for not taking the responsibility for creating conditions that support the health of their own staff. They claimed that the “wellness thinking”, which they tried to convey to the patients was absent at the management level.

Foster reflection and learning

Space and time for reflection and discussion was described as prerequisites for individual and organizational change and development. However, according to the health professionals, this space and time had become more and more restricted.

The time for reflection has disappeared ... there isn’t the opportunity.

Our informants did not express that lack of competence was the main barrier to health promotion. However, a few of them spoke about a need for more knowledge about health determinants and a need for improving their communication skills.

I think we need more and new knowledge about what promotes health and the causes for ill-health. We also need more knowledge about how to deal with this in practice so that we can contribute to give people back the power over their own health.

Something one has to learn as a doctor: how I talk to a person without taking on all the responsibility myself? A great portion comes from the individuals themselves and that is something one wants to teach oneself to pick out, and we can’t do that today, at least not me.

In general, the possibilities for professional development were described as minimal. There were limited opportunities for both collegial exchange and for participating in courses.

Utilize existing health promotion competence

The under utilization of existing health promotion competence and ideas was perceived as a much larger problem than lack of competence. Enabling collegial exchange and encouraging co-workers to make use of their competence was seen as most essential.

A balance between resources and assignments

Allocate time

Lack of time was seen as a key barrier to be actively involved in health promotion. The last years’ rationalizations had meant more tasks to be accomplished in a shorter time span, with no room for further assignments.

When one cuts in the same breath, one cannot conduct development and research, one cannot take away the queues, one cannot increase the accessibility to health care ... yes, and then it is not fun for us who work with health and medical care other than as a utopia.

Besides limited opportunities for reflection and professional development, lack of time often meant that preventive measures were cut down to keep up with more immediate disease-oriented assignments. One informant argued that preventive work was seriously threatened and at risk of being totally taken out of the health service.

One has to save those who are sick and then one does not have the time to prevent, which means that even more become sick so that one has even more to take care of. So this prevention work does not amount to anything but perhaps one has to lift it out of the health service in some way.

Restricted time in consultations with patients also posed a risk for incorrect measures and for increased re-visits. An increased medicalization of the patient’s concerns could also follow since prescriptions of drugs may be perceived as less strenuous than carrying on a conversation with the patient.

I believe that I and many others with me would work towards health promotion if we refrained from prescribing medicine, for example, and instead, shaping more the right expectations that this condition does not need any treatment, the body is good at healing itself ... That one works more with that but that requires more words, it requires more effort from the doctor’s part than writing a prescription, but I think that it is much more health promoting.

The health professionals underscored how more time will contribute to an overall improved quality of the health services, possibilities for having a proactive stance and being supportive to patients and relatives. Furthermore, it would improve the prospects for collegial support as well as engagement in development/improvement efforts. Accordingly, they saw a clear need for additional resources or re-allocation of available resources.

Take one step at a time

The health professionals pointed out that a health-promoting vision/assignment must be realistic and based on available resources. Aiming too high was considered as utopian and provoking. Thus, the work for change towards a more health-promoting health service must be considered as a long-term process. It was regarded as important to look beyond the next fiscal year. Moreover, the aim must be built on, by feasible subtargets, describing what shall be achieved year by year. They underscored that the long-term approach requires organizational stability concerning political control, organization of work and budget planning. The current constant organizational changes were described as devastating, breaking down functional work groups and modes of working.

Freedom of action

Even though the health professionals wished for guidelines, they called for freedom of action in their practice. They were full of suggestions with respect to the implementation; ideas that were just waiting to be utilized. Directives from above were seen as only causing frustration while a bottom-up perspective was considered effective.

Sometimes I think that this county council is too fond of it coming from above instead of actually taking advantage of the visions that exist. If this county council is going to be promoting health then one must begin out there.

Simplify the decision-making process

Freedom of action demanded a simplification of the decision-making process. The health professionals felt that they possess the will and knowledge about what to do but the system is too bureaucratic and hierarchical. They talked about the need for a slimmer organization and were not reluctant to suggest placement of the health service under private ownership as an alternative.

The will is there but the system is so difficult; there are too many rules, laws, musts, it just isn’t possible to work any other way.

Accept new, creative ideas

Freedom of action about how to extend the health-promoting role in their own units also implied greater acceptance of new ideas and creativity.

One does not receive acceptance for different ways of thinking or that one wants to do something, try something. And it is never possible to do anything other than that which is already decided.

Rely on co-workers’ ability

Finally the health professionals demanded that the management should rely more on the co-workers’ ability to carry out their work adequately. A failure should not be seen as “a big deal” but as better than not trying at all.

There is no confidence or trust that we will be able to do things independently.

Discussion

Methodological considerations

This study started off with focus group discussions with physicians and nurses. However, to be able to mirror the range and variation in perceptions among a broader group of health professionals, we decided to include occupational therapists, counselors, physical therapists, assistant nurses and midwives in the study. We considered including psychologists and dieticians also, but because the two last discussions did not generate much new information we decided not to. Because our aim was not to compare the views of different professional groups, the over-representation of physicians and nurses was not regarded crucial but created an awareness of the importance to also include views from the other groups in the analysis. A strength of the overall study is the interdisciplinary competence represented in the research team (nursing, medicine, physiotherapy, social work, and staff management) which enriched the peer-debriefing sessions, regularly held during the analytical process.

Results discussion

In our study the health professionals were able to identify health promotion and/or disease prevention as an important aspect of their professional role and the majority also expressed a need and a desire for an enhanced health promotion practice. The will or desire to act is an essential component of individual and organizational health promotion capacities.Citation13,Citation14 The perceived need of an enhanced health promotion practice can act as an important driving force for change. However this driving force was limited among our informants, who experienced a range of organizational and working conditions that negatively influenced their efforts to practice health promotion and engage in improvement/development work. The perceived gap between the desire to work more with health promotion and prevention and the perceived possibilities resulted in a sense of frustration and resignation accompanied by a feeling of disempowerment within the system.

International research has indicated that the capacity of health professionals to engage in health promotion work is influenced by factors over which they have limited control. These factors are largely determined by the characteristics of the organization.Citation15

Organizational structures that provide resources, support and the opportunity to learn and develop are empowering and enable employees to accomplish their work.Citation16 They will be more committed to the organization and consequently more productive and effective in meeting organizational goals. Organizational commitment is of particular importance to health care organizations where employees are struggling to maintain high-quality patient care with fewer resources.Citation17 Thus, it is important for the health services management to encourage commitment by ensuring that structures are in place to allow accomplishment of meaningful goals.Citation17

A more health-promoting health service implies changes on an individual as well as on an organizational level.Citation18,Citation19 Our informants stressed that it requires completely new ways of thinking and working and that it calls for great changes in the whole organization. Having a vision, a plan of where to go is not enough. One must also consider the process of how to get there.Citation19 As indicated by our informants, directives from “above” do not always get a friendly reception. The reason is that the primary driving force for change is from staff needs and ideas.Citation20 A sense of ownership and autonomy with regard to one’s work are important motivational factors.Citation15 Involving staff at all levels in the change process is therefore an important component of organizational change framework.Citation15

The process of change requires allocation of time. As pointed out by our informants, it must be possible to reflect and discuss thoughts and ideas. Yet, due to production “always being prioritized”, it is difficult to find time for it. Leaders and staff must therefore create space and allocate time for this task in the everyday workload otherwise there is a risk of failure in an already overburdened work situation.Citation21

The health professionals called for freedom of action in their practice which demands a simplification of the decision-making process. This is in line with the domain theory as described by Kouzes and Mico.Citation8 The theory suggests that the management domain is dominated by “technocratic bureaucracy”; meaning that the governing principles are hierarchical control and coordination. The service providers also see themselves as having rights to control what they define as their professional domain. They consider themselves capable of self-governance and believe they have the expertise to respond to the needs of the client. Thus, they demand autonomy. Since decisions made in each domain impact upon the other, each struggles to maintain integrity and seeks to balance the power in the system. According to Kouzes and Mico, tensions and conflicts between the domains are almost continually present.Citation8

The fact that lack of time and resources was identified as one of the core constraints is well recognized by others.Citation22–Citation33 The health professionals agreed that there is a need for more staff to improve the chances of a more health-promoting health service. There is simply a need of “more horses to pull the wagon” as one of the health professionals expressed it. A reasonable balance between tasks and resources is an obvious requirement for providing good service. Others have pointed how essential adequate financial/human resources are for efficient and effective health actions.Citation13,Citation15 Accordingly, the organizations must allocate resources necessary to increase the capacity of health promotion. However, it’s not only about allocating additional resources but also about making the most of existing ones. According to Cederqvist and Hjortendal Hellman, there is potential for increasing the cost-effectiveness of the Swedish health care system.Citation34 Re-allocations of resources can produce a higher value for patients as well as an improved work environment for staff.

To be an effective health promotion practitioner requires a range of competencies.Citation15,Citation35 In contrast to previous research our study did not disclose lack of competence as a key barrier to health promotion.Citation14,Citation22–Citation25,Citation31–Citation33 This was not focused on specifically in our discussions but our interpretation is that the health professionals to a large extent considered themselves to possess adequate competence. However, the need for increased health promotion competence, especially in form of empowering communication skills was emphasized among the physicians, probably reflecting limitations in their educational training. Since development of human capital in form of individual knowledge and skills is important to organizational capacity for health promotion the organization must ensure that all staff has relevant competences to perform health promotion activities and create structures that facilitate the acquisition of further competences as required.Citation16

Promoting health in others was described by the health professionals as an “advanced task” calling not only for great skills and engagement but also for physical and mental strength. Our results emphasize the need for encouraging health promotion for the staff themselves. The management must establish conditions for hospitals and health centre’s to become healthy workplaces with active support for health promotion activities for the staff.

Health professionals also have to find ways to reorient themselves to focus more on possibilities than on existing barriers. One possible way is to think about health promotion as an empowering, holistic, individualized approach applicable to any interaction instead of a new added on task. Then they can ask themselves; “what tasks that I perform today am I already doing in a health-promoting manner?”

Since this study addresses health professionals as a group it raises questions about how the identified barriers and possibilities for having a health-promoting role in practice are distributed among health professional groups with varying educational background and working experiences. This will be further explored in a forthcoming quantitative study.

This study, however, clearly showed that health professionals are willing to and have a desire for developing their health-promoting and/or preventive role at the same time feeling limited by existing values, structures and resources. This indicates that an organizational setting that support health promotion practice is still to be developed. There is a need for a more explicit leadership with a clear direction towards the goal of “a more health-promoting health service” and with resources that are sufficient for reaching that goal. The health professionals’ own resources have to be mobilized and better utilized. New ideas and staff engagement must be recognized and encouraged.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken within the Centre for Global Health at Umeå University, with support from FAS, the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (grant no. 2006-1512). The study was also partly supported by the County Council of Västerbotten and by Ageing and Living Conditions, (ALC), CPS, Umeå University, Sweden. We want to thank the health professionals for their willingness to participate in the focus group discussions. We also want to thank Berit Nyström, one of the research team members, for her strong commitment during the research process. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Notes

a The distinction between health promotion and disease prevention efforts and the willingness to take on a preventive role but not a health promotion role has been described in another paper.Citation12

References

- World Health OrganizationOttawa Charter for Health PromotionCopenhagen, DenmarkWHO Europe1986

- WiseMNutbeamDEnabling the systems transformation: what progress has been made in re-orienting health services?Promot Educ2007Suppl 2232717685076

- Government billRegeringens proposition 2002/03:35Mål för folkhälsan [National public health objectives]Stockholm, Swedensocialdepartementet2002

- Government billRegeringens proposition 2007/08:110En förnyad folkhälsopolitik [An updated public health policy]Stockholm, Swedensocialdepartementet2007

- PetterssonBTransforming Ottawa Charter health promotion concepts into Swedish public health policyPromot Educ20071424424918372877

- The National Institute of Public Health (Statens Folkhälsoinstitut)Kunskapsunderlag till folkhälsopolitisk rapport 2005 Målområde 6 – En mer hälsofrämjande hälso- och sjukvård [Knowledge base for public health political report 2005 Goal area 6 – A more health promoting health and medical care]Stockholm, SwedenThe National Institute of Public Health2005

- The National Swedish Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen)Hälso- och sjukvårdsrapport [Health care report]Stockholm, SwedenSocialstyrelsen2001

- KouzesJMMicoPRDomain Theory: An introduction to organizational behavior in human service organizationsJ Appl Behav Sci197915449469

- BarbourRSKitzingerJDeveloping Focus Group Research: Politics, theory, and practiceLondon, UKSage Publications2001

- GraneheimUHLundmanBQualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthinessNurse Educ Today20042410511214769454

- LundmanBHällgren GraneheimUKvalitativ innehållsanalys. [Qualitative content analysis]GranskärMHöglundBTillämpad Kvalitativ Forskning Inom Hälso- och Sjukvård. [Applied Qualitative Research Within Health and Medical Care]Stockholm, SwedenStudentlitteratur2008159172

- JohanssonHWeinehallLEmmelinM“It depends on what you mean”: A qualitative study of Swedish health professionals’ views on health and health promotionBMC Health Serv Res2009919119845948

- PearsonTAShankle-BalesVBlairLThe Singapore declaration. Forging the will for heart health in the next millenniumCVD Prevention and Control19981182199

- AnderssonDRaineKDPlotnikoffRCCookKBarrettLSmithCBaseline assessment of organizational capacity for health promotion within regional health authorities in Alberta, CanadaPromot Educ200815614

- Mc LeanSFeatherJButler-JonesDBuilding Health Promoting Capacity: Action for learning, learning from actionVancouver, CanadaUBC Press2005

- KanterRMMen and Women of the Corporation2nd EdNew York, NYBasic Books1984

- LaschingerHKFineganJShamianJCasierSOrganizational trust and empowerment in restructured healthcare settings: Effects on staff nurse commitmentJ Nurs Adm20003041342511006783

- JohnsonABaumFHealth promoting hospitals: a typology of different organizational approaches to health promotionHealth Promot Int200116328128711509465

- HewardSHutchinsCKeleherHOrganizational change – key to capacity building and effective health promotionHealth Promot Int20072217017817495992

- StenbergJOlssonJTransformera system-från öar till helhet Ett diskussionsunderlag [To transform systems – from isolated islands to include the whole A basis of discussion]Stockholm, SwedenSveriges kommuner och landsting2005124

- BackmanLLeijonOLindbergMPernoldGPettersonILAtt skapa hälsofrämjande arbetsplatser inom vård och omsorg – en kunskaps-sammanställning. [Creating health-promoting workplaces within health care system]Stockholm, SwedenArbets och miljömedicin2002

- JoffresCHeathSFaraquharsonJDefining and operationalizing capacity for heart health promotion in Nova Scotia, CanadaHealth Promot Int200419394914976171

- WhiteheadDThe European health promoting hospitals project: how far on?Health Promot Int20041925926715128717

- BrotonsCBjörkelundCBulcMPrevention and health promotion in clinical practice: the views of general practitioners in EuropePrev Med20054059560115749144

- JacobsenETRasmussenSRChristensenMEngbergMLauritzenTPerspectives on lifestyle intervention: The views of general practitioners who have taken part in a health promotion studyScand J Public Health20053341015764235

- LindbergMWilhelmssonS“Vem bryr sig” Distriktssköterskans förebyggande och hälsofrämjande arbete – ett svårprioriterat uppdrag [“Who cares” The district nurse’s preventive and health-promoting work – a difficult to prioritize assignment]Stockholm, SwedenFammi2005

- McKinlayEPlumridgeLMcBainLMcLeodDBrownS“What sort of health promotion are you talking about?”: a discourse analysis of the talk of general practitionersSoc Sci Med2005601099110615589677

- RobinsonKLDriedgerMSElliottSJEylesJUnderstanding facilitators of and barriers to health promotion practiceHealth Promot Pract2006746747616885509

- RyanRGarlickRHappellBExploring the role of mental health nurse in community mental health care for the agedIssues Ment Health Nurs2006279110516352518

- JerdenLHillervikCHanssonACFlackingRExperiences of Swedish community health nurses working with health promotion and a patient-held health recordScand J Caring Sci20062044845417116154

- WhitelawSMartinCKerrAWimbushEAn evaluation of the Health Promoting Health Service Framework: the implementation of a settings based approach within NHS ScotlandHealth Promot Int200621213614516585132

- CaseyDNurses’ perceptions, understanding and experiences of health promotionJ Clin Nurs2007161039104917518880

- GuoXHTianXYPanYSManagerial attitudes on the development of health promoting hospitals in BejiingHealth Promot Int20072218218917495993

- CederqvistJHjortendal HellmanEIakttagelser om landsting. [Observations of county councils]Stockholm, SwedenFinansdepartementet2005

- IrvineFExploring district nursing competencies in health promotion: the use of the Delphi techniqueJ Clin Nurs20051496597516102148