Abstract

Bipolar depression is more common, disabling, and difficult-to-treat than the manic and hypomanic phases that define bipolar disorder. Unlike the treatment of so-called “unipolar” depressions, antidepressants generally are not indicated as monotherapies for bipolar depressions and recent studies suggest that -even when used in combination with traditional mood stabilizers – antidepressants may have questionable value for bipolar depression. The current practice is that mood stabilizers are initiated first as monotherapies; however, the antidepressant efficacy of lithium and valproate is modest at best. Within this context the role of atypical antipsychotics is being evaluated. The combination of olanzapine and the antidepressant fluoxetine was the first treatment to receive regulatory approval in the US specifically for bipolar I depression. Quetiapine was the second medication to be approved for this indication, largely as the result of two pivotal trials known by the acronyms of BOLDER (BipOLar DEpRession) I and II. Both studies demonstrated that two doses of quetiapine (300 mg and 600 mg given once daily at bedtime) were significantly more effective than placebo, with no increased risk of patients switching into mania. Pooling the two studies, quetiapine was effective for both bipolar I and bipolar II depressions and for patients with (and without) a history of rapid cycling. The two doses were comparably effective in both studies. Although the efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy has been established, much additional research is necessary. Further studies are needed to more fully investigate dose-response relationships and comparing quetiapine monotherapy to other mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, and lamotrigine) in bipolar depression, both singly and in combination. Head-to-head studies are needed comparing quetiapine to the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination. Longer-term studies are needed to confirm the persistence of response and to better gauge effects on metabolic profiles across months of therapy. A prospective study of patients specifically seeking treatment for rapid cycling and those with a history of treatment-emergent affective shifts also is needed. Despite the caveats, as treatment guidelines are revised to incorporate new data, the efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine monotherapy must be given serious consideration.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a highly recurrent and not infrequently chronic illness that is recognized as one of the world’s 10 greatest public health problems (CitationMurray and Lopez 1997). For the majority of patients, the periods of depression far exceed those of mania, in terms of both frequency and duration (CitationPost et al 2003; CitationJudd et al 2002, Citation2003). For individuals with bipolar I disorder, for example, days spent with depressive symptoms are about three times more common than days spent with hypomanic or manic symptoms (CitationJudd et al 2002). The dominance of the depressed pole of the illness is even more dramatic individuals with bipolar II disorder: in one prospective study conducted across nearly 13 years, patients with bipolar II disorder spent almost 40 times the days with depressive symptoms as compared to the days spent with hypomanic symptoms (CitationJudd et al 2003).

Despite the dramatic and life-disrupting nature of mania, recent studies have also documented that it is the more long-lasting depressive episodes that have the greater deleterious effects on quality of life and functionality (CitationJudd et al 2005; CitationDepp et al 2006). The burden imposed by bipolar depression on the family and loved ones exceeds that of bipolar mania or unipolar depression, perhaps all the more remarkable in view of the greater risk of psychosis, violent behaviour, and increased frequency of hospitalization associated with mania (CitationPost 2005; CitationHirschfeld 2004). The perceived stigma of the condition may also add to the burden placed on the family or primary caregiver (CitationPerlick et al 2004). The assessment of caregiver burden is further impeded by the unique characteristics of bipolar depression – including the unfortunate tendency for milder episodes to go unrecognized or untreated and the high incidence of subsyndromal inter-episode symptoms (CitationOgilvie et al 2005). Perhaps not surprisingly, the depressive episodes also are more directly linked to reduced longevity in bipolar disorder, particularly through suicide but perhaps also to increased risks of obesity and cardiovascular disease (CitationDilsaver et al 1997; Fagiolini et al 2002; CitationMitchell and Malhi 2004).

Despite the obvious clinical importance of the depressed phase of bipolar disorder, remarkably few controlled studies of first- and second-line treatments have been performed (CitationThase 2005). The paucity of well-designed studies essentially precludes the practice of evidence-based medicine and for some important questions (eg, “If an antidepressant is used and appears to be effective, how long should it be maintained?”) there is not consensus about best practices, which no doubt hampers clinical decision-making (CitationThase 2005; CitationOstacher 2006). Indeed, in the largest placebo-controlled study of the role of antidepressants in bipolar depression conducted to date, the addition of paroxetine or bupropion to optimized therapy with mood stabilizers resulted in no added benefit as compared to therapy with mood stabilizers alone (CitationSachs et al 2007). For the prescribing physician, the need to swiftly deliver effective pharmacotherapy to lessen suffering and minimize functional impairments is paramount, and appears to foster the continued use of antidepressants in bipolar depression despite the lack of clear-cut evidence that they improve outcomes. Nevertheless, the decision to initiate therapy with an antidepressant to hasten recovery is not without attendant risks, including treatment-emergent affective switches (TEAS) or acceleration of cycling and, as a result, the ranking of antidepressants in contemporary practice guidelines continues to drop in favor of other strategies (CitationThase 2005; CitationYatham et al 2006).

Many expert panels recommend initiating mood stabilizers alone, ie, before considering whether or not an antidepressant is indicated. If one accepts the validity of the “mood stabilizer first” strategy, then lithium and three anticonvulsants (valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine) might be nominated as candidates for first line of therapy for bipolar depression (CitationThase 2005; CitationGrunze 2005). However, none of these medications is renowned for having powerful antidepressant effects (CitationThase 2005) and – primarily for reasons of tolerability and safety – few clinicians would use carbamazepine as the first step in a treatment algorithm. Even lithium salts, which arguably have the best evidence of efficacy from placebo-controlled studies (CitationZornberg and Pope 1993; Thase and Sachs 2000), do not exert particularly robust antidepressant effects (CitationThase 2005). The search for an effective monotherapy for bipolar depression thus goes on.

Emerging data suggest that the list of medications that are classified as mood stabilizers eventually may need to be expanded to include the class of medications known as atypical antipsychotics. All five of the more widely prescribed atypical antipsychotics (in alphabetical order: aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone) have established antimanic efficacy. Consistent with proposed criteria to define mood stabilizers (see, for example, CitationKetter and Calabrese 2002; CitationGoodwin and Malhi 2007), atypical antipsychotics are unlikely to cause TEAS and two members of the class (olanzapine and aripiprazole) have received a formal indication for prophylaxis against manic relapse following successful acute therapy. Starting with observations from studies that included patients with mixed manic states, there is slowly increasing evidence to indicate that atypical antipsychotics also have antidepressant effects (CitationKeck 2005; CitationNemeroff 2005). In fact, the first treatment to be approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for bipolar depression is the proprietary combination of olanzapine and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), fluoxetine. In the pivotal trials that led to that indication, olanzapine monotherapy was also studied and found to have intermediate efficacy: greater than placebo but significantly less than the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination (OFC) (CitationTohen et al 2003).

This review will focus on the second atypical antipsychotic to be systematically studied as a monotherapy for bipolar depression, quetiapine. The results of the research program that led to the FDA approval of quetiapine monotherapy for bipolar depression will be summarized in detail. Quetiapine, which is the first – and currently only – monotherapy approved by the FDA to treat both the depressive and manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder, has been ranked as a first-line treatment of bipolar depression in the recently updated treatment guidelines published by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) (CitationYatham et al 2006).

Efficacy against depressive symptoms

Regulatory approval of quetiapine monotherapy for bipolar depression was primarily based on two similar randomized controlled trials (RCTs) known by the acronyms BOLDER (BipOLar DEpRession) I and II. Both of these 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies compared two doses of quetiapine – 300 mg per day and 600 mg per day. Both studies used once daily dosing (at bedtime) and the same rapid titration schedule, with maximum study dose achieved by the 8th day of treatment. Both studies included patients with bipolar I and bipolar II depressive episodes and allowed otherwise eligible patients with histories of rapid cycling to enroll. Both studies used change in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score as the primary endpoint. Together, the BOLDER I (CitationCalabrese et al 2005) and BOLDER II (CitationThase et al 2006) studies represent the largest placebo-controlled data set to date that includes patients with bipolar I and bipolar II depressions.

BOLDER I enrolled 542 patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for a current episode of bipolar I or bipolar II depression, according to DSM-IV criteria (CitationCalabrese et al 2005). In order to enter the study, outpatients had to score at least 20 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D17), as well as have a score of at least 2 on HAM-D item 1 (depressed mood). Pretreatment MADRS scores indicated that the unmedicated study group presented with moderate-to-severe levels of depressive symptoms (see, for example, CitationMuller et al 2003).

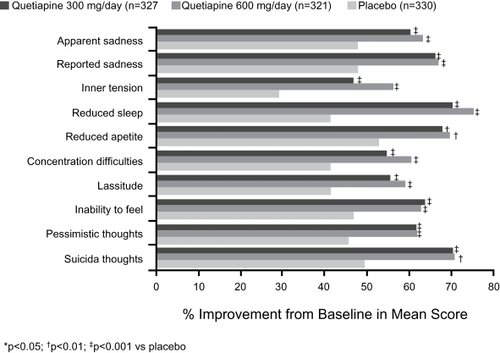

Both doses of quetiapine resulted in significant improvements in MADRS total scores at all time points measured, with statistical significance over placebo detected after only 1 week of treatment (the first assessment point of the study) and maintained at every time point thereafter (see ). The proportion of patients classified as responders to treatment, defined as a ≥50% improvement in MADRS total score at study endpoint (using the “last observation carried forward [LOCF] convention” to estimate the final scores of study dropouts) was significantly higher in both groups receiving active quetiapine (58% in both groups) than in the group randomized to placebo (36%). Remission rates (defined as a final MADRS total score ≤12) followed a similar pattern (53% for both 300 mg and 600 mg quetiapine, 28% for placebo). Individuals treated with either dose of quetiapine were faster to respond to treatment and to achieve remission than those receiving placebo (median time to response was 22 days for both doses of quetiapine versus 36 days for placebo, and median times to remission were 29, 27, and 65 days for 300 mg quetiapine, 600 mg quetiapine, and placebo, respectively).

Figure 1a Least-squares mean change from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score at each assessment of outpatients with bipolar I or II disorder who experienced a major depressive episode (BOLDER I).

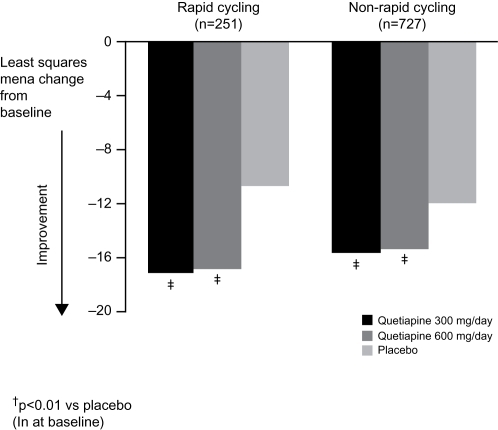

The results of the BOLDER II trial (n = 509) fully replicated the first study in terms of the primary outcome variable, with quetiapine-treated patients displaying significantly greater mean improvement in MADRS total scores than placebo-treated patients at all time points from Week 1 onward () (CitationThase et al 2006). Response rates for both doses of quetiapine monotherapy were also similar to those observed in the original study after 8 weeks of treatment (60%, 58%, and 45% for the 300 mg, 600 mg, and placebo groups, respectively), as were remission rates (52% for both groups receiving active quetiapine as compared to 37% for the group receiving placebo). Looking across the two studies, the only appreciable difference was the higher placebo response/remission rates observed in BOLDER II, which could possibly be attributable to increased expectations from physicians and patients alike, in light of the positive findings arising from BOLDER I.

Figure 1b Least-squares mean change from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score at each assessment of outpatients with bipolar I or II disorder who experienced a major depressive episode (BOLDER II).

In both BOLDER studies, improvements on the secondary rater-administered measure, the HAM-D17, mirrored those reported on the MADRS scale. For example, both groups receiving active quetiapine again experienced significantly greater mean improvements from Week 1 onward compared with the group receiving placebo.

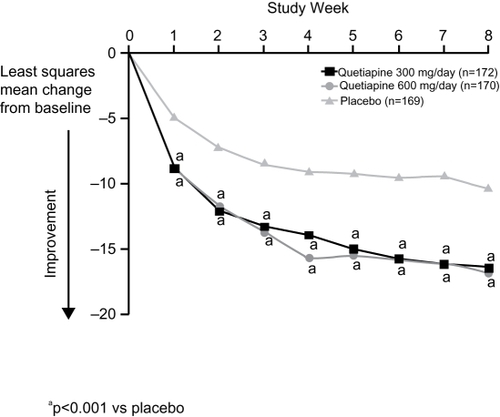

With respect to the impact of quetiapine on specific depressive symptoms, at study endpoint improvements were detected in nine of the 10 individual items in BOLDER I, and in nine individual items in BOLDER II. summarizes improvements in individual items of the MADRS scale in the BOLDER studies. It is important to note that significant improvements were observed on the core symptoms of depression, including apparent sadness, reported sadness, suicidal thoughts, and pessimistic thoughts, in addition to improvements in sleep and anxiety.

Efficacy in patient subgroups

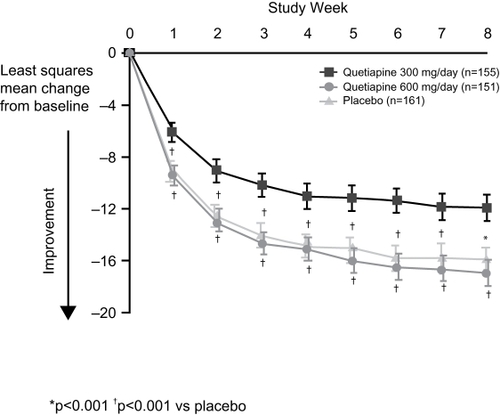

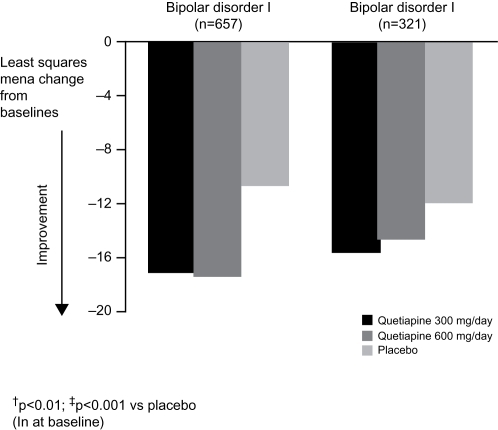

Since the patient populations enrolled in the BOLDER studies included individuals with both bipolar I and bipolar II depression, and those with and without a rapid-cycling disease course, the results of the BOLDER trials were examined to determine if quetiapine was particularly effective – or ineffective – in various patient subgroups. Although there are important differences between bipolar I and bipolar II disorders (as well as between patients who meet criteria for rapid cycling and those who do not) (CitationYatham et al 2005), demonstration that a novel treatment is comparably effective across the subgroups could greatly simplify clinical management. The combined BOLDER data set shows that both bipolar I and bipolar II patient groups exhibited significant improvements in MADRS total score following treatment with either dose of quetiapine (300 mg per day or 600 mg per day) compared with placebo ().

Figure 3 Least mean squares change from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score in outpatients with bipolar I or II disorder (data pooled from BOLDER I and BOLDER II studies; ITT, LOCF).

Rapid cycling is associated with a poorer treatment response and long-term prognosis, and is associated with greater disability and a higher incidence of suicidal behavior (CitationSchneck 2006). Currently available antidepressants may increase the risk of rapid cycling, and this uncertainty has limited their widespread use (CitationGoldberg and Truman 2003). Results of a subanalysis of BOLDER I indicated that quetiapine was as effective in patients with a history of rapid cycling as among with less frequent episodes (CitationVieta et al 2007). A not yet published analysis of the combined data from the BOLDER studies echoed this result and demonstrated the broad applicability of quetiapine treatment by revealing a similar improvement in MADRS total scores in both patients with or without rapid cycling (). As many experts consider antidepressants to be relatively contraindicated in rapid cycling because of an extremely high incidence of TEAS, the antidepressant activity of quetiapine could be partly offset if therapeutic response was associated with increased cycling or the induction of hypomania/mania. It is thus noteworthy that the rapid cycling patients treated with quetiapine in BOLDER I and BOLDER II were no more likely to develop hypomania or mania than were patients receiving placebo. Although patients were also assessed for signs/symptoms of treatment-emergent mood elevation with the Young Mania Rating Scale, to date results on this measure have not been reported. Nevertheless, as described below, the proportion of patients developing diagnosable episodes of hypomania or mania was actually higher among those treated with placebo than those receiving active quetiapine.

Efficacy against anxiety symptoms

Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with bipolar disorder and may predispose individuals to intensified symptoms, substance abuse, hospitalization, and suicide ideations (CitationGaudiano and Miller 2005; CitationKeller 2006; CitationMcIntyre et al 2006). A cross-sectional sample from 500 individuals with bipolar I or II disorder enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) indicated that comorbid anxiety disorders, which were identified in over half of the sample, had a large and negative impact on role functioning and quality of life (CitationSimon et al 2004a). The patient’s response to treatment can be dampened by comorbid anxiety (CitationFrank et al 2002; CitationGaudiano and Miller 2005), making pharmacotherapy a challenge. Despite the high comorbidity, many patients with bipolar disorder and a coexisting anxiety disorder do not receive appropriately tailored drug therapy. In the STEP-BD population mentioned above, only 59% reported pharmacotherapy use meeting criteria for “minimally adequate” mood stabilizer, regardless of comorbid diagnoses, rapid cycling, or bipolar I or II status (CitationSimon et al 2004b). Moreover, even though anticonvulsants may have some utility for patients with comorbid anxiety, such patients are less responsive to therapy than non-anxious patients (CitationHenry et al 2003). Given the paucity of existing data and the clear need for improved treatment options in this patient subset, it was important to examine the effect of quetiapine monotherapy on anxiety symptoms in the BOLDER studies.

In the BOLDER I study, mixed model for repeated measurements (MMRM) analysis of anxiety symptoms, as rated on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A), revealed that quetiapine monotherapy was associated with a rapid and pronounced improvement across individual and combined quetiapine treatment groups compared with placebo (−10.3 versus −6.7 for combined quetiapine and placebo groups, respectively), irrespective of baseline severity of depression (CitationHirschfeld et al 2006). Improvements were seen in eight of the 14 individual items on the HAM-A scale, which included the core items of “anxious mood” (−1.1 versus −0.5, respectively; p < 0.001)and “tension” (−1.1 versus −0.6 respectively; p < 0.001). This improvement was replicated in the BOLDER II study, in terms of both magnitude and significance (CitationThase et al 2006).

Improvement in anxiety symptoms was observed in the subgroup of bipolar I patients in BOLDER I, in which HAM-A total score was significantly improved compared with placebo at Week 8 (−10.4 versus −5.1 points, for combined quetiapine and placebo groups, respectively; p < 0.001) (CitationHirschfeld et al 2006). Within the smaller subset of patients with bipolar II disorder, patients treated with active quetiapine or placebo showed comparable improvement in HAM-A total score (−9.8 versus −9.0, respectively). Results from subgroup analyses from the BOLDER II trial and the pooled data set, not yet available, will be helpful in clarifying this unexpected finding.

Effects on other secondary outcome measures

Quality of sleep

Sleep disturbance is a relatively common occurrence in psychiatric patients, with insomnia presenting as a primary symptom in 30%–90% of psychiatric disorders. (CitationBecker 2006)Again, the BOLDER I study was the first to explore the impact of quetiapine monotherapy on sleep, using the Pittsburgh questionnaire (PSQI) to rate quality of sleep. The PSQI is a 24-item questionnaire that includes 19 self-rated and 5 items rated by the patient’s bed partner. The instrument is used to study sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency, use of medication, and daytime dysfunction, and assesses sleep quality and disturbance in the preceding month.

In BOLDER I, participants showed moderate-to-severe sleep disruption at baseline according to the PSQI. At last assessment, quality of sleep had improved significantly following treatment with either dose of quetiapine compared with placebo (p < 0.001) (CitationEndicott et al 2007). Mean values for quality of sleep, sleep latency, and sleep duration were 0.5–0.7 points lower in quetiapine-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients (CitationEndicott et al 2007).

Quality of life

To date, dedicated quality-of-life studies in individuals with bipolar disorder are relatively sparse, although a number of ongoing studies are attempting to redress this imbalance in response to increased recognition that recovery should be marked by a return to an acceptable quality of life and improved functionality for the patient (CitationMichalak et al 2005; CitationMitchell et al 2006; CitationKasper 2004). The depressive component of bipolar disorder is thought to be more detrimental to quality of life than the manic component (CitationVojta et al 2001). Furthermore, the degree of functional impairment and loss of work productivity experienced by individuals with bipolar depression exceeds that experienced by patients with unipolar depression (CitationVornik and Hirschfeld 2005). There is also evidence to suggest that the delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis experienced by many individuals with bipolar depression may further impact the quality of life they are able to enjoy since early and appropriate intervention can drastically enhance not only the symptomatic but also the subjective experience of individuals over the long term (CitationKasper 2004).

Thus, any efficacious medication that can also exert positive effects on quality of life in bipolar depression is of obvious therapeutic value. Positive effects on health-related quality of life may be intrinsically linked with general tolerability. If a treatment is well-tolerated, a patient will be more likely to become satisfied with his treatment regimen. The superiority and increasing popularity of the atypical antipsychotics over the more conventional antipsychotics may derive from their improved tolerability (CitationVornik and Hirschfeld 2005).

The BOLDER I study was the first large-scale investigation of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar depression to report quality of life as a secondary endpoint (CitationEndicott et al 2007). Both BOLDER studies used the short-form version of the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) to evaluate the impact of quetiapine on health-related quality of life. This version rates 16 items (physical health; mood; work; household activities; social relationships; family relationships; leisure-time activity; ability to function in daily life; sexual drive, interest and/or performance; economic status; living/housing situation; ability to get around physically without feeling dizzy or unsteady or falling; vision in terms of ability to work or do hobbies; overall sense of well-being; medications; and overall life satisfaction and contentment during the past week) on a 5-point scale.

Consistent with their disease profile, BOLDER participants scored poorly on quality-of-life scores at baseline. Following 8 weeks of treatment with quetiapine, significant improvements in Q-LES-Q total score were evident in both BOLDER studies (CitationCalabrese et al 2005; CitationThase et al 2006; CitationEndicott et al 2007). In BOLDER I, for example, mean Q-LES-Q percentage maximum scores at final assessment (LOCF) were 57.6, 57.4, and 48.1 points for 300 mg quetiapine, 600 mg quetiapine, and placebo, respectively (CitationEndicott et al 2007). The improvements were significantly greater in both quetiapine groups compared with placebo (p < 0.001) at final assessment. Interestingly, quality-of-life improvements were positively linked with MADRS response and remission status. If a patient responded to quetiapine treatment, quality of life also improved, whereas MADRS non-response was associated with negligible improvement in quality of life.

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), introduced as an additional outcome measure for BOLDER II, quantified the impact of quetiapine on the interrelated domains of work, social life, and family life/home life/responsibilities. At the last assessment, the mean improvements in SDS scores from baseline were −7.3, −7.9, and −6.0 for 300 mg quetiapine, 600 mg quetiapine, and placebo, respectively (p < 0.05 for 600 mg quetiapine versus placebo) (CitationThase et al 2006).

Tolerability profile

Good tolerability, as rated by physicians and patients alike, is integral to the success of any medication strategy. As tolerability and treatment adherence tend to worsen as each new drug is added to a complex pharmacotherapy regimen, a well-tolerated monotherapy would be expected to have multiple advantages. (CitationBurton et al 2005)Quetiapine monotherapy was generally well-tolerated in the BOLDER studies. As detailed safety/tolerability data were presented in the source publications, (CitationCalabrese et al 2005; CitationThase et al 2006)only a brief summary follows below.

Treatment discontinuations and adverse event (AE) incidence

In the BOLDER studies, the proportions of quetiapine-treated patients completing the full 8 week treatment protocol was similar to that reported for placebo and ranged between 53% and 67%. The most common reasons for discontinuation were withdrawal of consent, adverse events, loss to follow-up, and lack of perceived efficacy, with attrition due to AEs more common among the patients receiving active medication and dropouts due to lack of efficacy more common in the placebo groups. None of the serious AEs reported in either BOLDER study was considered to have been drug-related.

The majority of AEs were mild-to-moderate in intensity and transient in nature. The most common adverse events experienced by 5% or more of patients receiving quetiapine in both BOLDER studies were dry mouth, sedation, somnolence, dizziness, and constipation (; pooled data from BOLDER I and II). Trends in tolerability tended to favor the group receiving the lower (300 mg per day) dose, although few of these differences were statistically significant.

Table 1 Most common adverse events associated with quetiapine treatment in outpatients with bipolar I or II disorder (≥5% patients; data pooled from BOLDER I and BOLDER II studies)

Weight change

Weight gain in the BOLDER studies was greater among the patients receiving active quetiapine. Across studies, the pooled weight-gain data showed a mean increase of 1.2 kg in the quetiapine 300 mg per day group and 1.5 kg in the 600 mg per day group, as compared with a gain of 0.2 kg in the placebo group. A weight increase of greater than 7% was observed in 7.1% of patients receiving the 300 mg/day dose of quetiapine, 10.0% receiving the 600 mg/day dose of quetiapine, and 2.4% of those receiving placebo.

The weight gain associated with some atypical antipsychotics may often be accompanied by deleterious changes in serum lipids and increases in fasting glucose, both of which increase the risk for coronary artery disease. It is important to note that in the BOLDER trials, the mean change in fasting glucose and lipids with quetiapine was not statistically significantly different to that with placebo.

Treatment-emergent mania

As discussed previously, the risk of precipitating a manic episode is a major concern when treating bipolar depression with traditional antidepressants. Treatment-emergent mania affects 20%–40% of individuals with bipolar disorder receiving long-term antidepressant therapy (CitationGoldberg and Truman 2003). Since combination therapy may reduce the risk of treatment-emergent mania, this is often the treatment approach preferred by many psychiatrists (CitationGrunze 2005). Therefore, when assessing the tolerability profile of a single agent, it is important to establish the propensity for manic switch.

Data from the BOLDER studies showed a low incidence of treatment-emergent mania with quetiapine and placebo. Treatment-emergent mania was defined as an adverse event of mania or hypomania, or Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score ≥16 on any two consecutive visits or at the final visit. Data pooled from BOLDER I and II reveal that the proportion of patients with treatment-emergent manic symptoms was greater in the placebo group (5.2%) compared with both quetiapine treatment groups (both 2.9%).

EPS-related AEs

Historically, the atypical antipsychotics have been associated with a reduced risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) within the recommended dose ranges compared with their conventional counterparts (CitationPierre 2005). This highly desirable characteristic is thought to derive directly from their mechanism of action, specifically by less avid binding to post-synaptic dopamine receptors in the basal ganglia (CitationSeeman 2002; CitationTort et al 2006).

In the BOLDER trials, no individual specific EPS had an incidence greater than 5% among patients receiving quetiapine and the rate of discontinuation due to EPS was also low. The incidence of the abnormal involuntary movements that were considered to be EPS was 12.0% with quetiapine 300 mg per day, 11.5% with quetiapine 600 mg per day, and 5.5% with placebo. Mean changes in scores from rating scales used to assess EPS, the Simpson-Angus Scale and the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, were low in the quetiapine treatment groups and were similar to those reported for placebo.

Long-term efficacy

One significant limitation of the BOLDER studies is that they were limited to only 8 weeks of double-blind therapy and patients were withdrawn from study medication at the completion of the study. In clinical practice, an effective monotherapy of bipolar depression would typically be maintained indefinitely for prophylaxis. To date, the long-term effects of quetiapine in bipolar depression have only been assessed in a small open-label study (CitationMilev et al 2006), and with quetiapine (at doses up to 800 mg/day) being used in combination with ongoing antidepressant or mood stabilizing therapy. A naturalistic 12-month study in 17 patients revealed a mean reduction in baseline HAM-D total score of 55.5% LOCF following the addition of quetiapine to the existing treatment regimen (CitationMilev et al 2006). The proportion of patients (n =13) achieving a 50% reduction in HAM-D17 total score was high, at 76.5%. Although these preliminary data are encouraging, larger controlled studies are required to extend these long-term findings and to examine the long-term effects of quetiapine monotherapy in particular. Maintenance studies with quetiapine in bipolar disorder are currently under analysis. The impact of longer term quetiapine therapy on weight and other metabolic indices will be of considerable interest.

Relative efficacy

Another limitation of the BOLDER studies is that neither study included an active comparator. Now that efficacy has been established, comparative studies are needed, both versus conventional mood stabilizers such as lithium and valproate, and the olanzapine – fluoxetine combination (OFC) (the only other treatment strategy now approved for treatment of bipolar depression). Some would argue that head-to-head comparisons versus lamotrigine also are needed. Although the acute phase efficacy of lamotrigine has not yet been established by a series of unequivocally positive RCTs, it is widely used by clinicians for treatment of both bipolar I and bipolar II depression and there is, at the least, evidence suggestive of efficacy in the literature (CitationCalabrese et al 1999; CitationFrye et al 2000). In the only study to directly compare lamotrigine and OFC, trends favoured the latter drug on efficacy measures, although tolerability indices clearly favoured lamotrigine (CitationBrown et al 2006). In addition to studies of quetiapine as a monotherapy, its utility in combination with other relevant therapies, both antidepressants and conventional mood stabilizers, warrant evaluation.

Is quetiapine a mood stabilizer?

There is currently a lack of consensus surrounding the label “mood stabilizer,” but generally, if an agent shows efficacy in treating both acute manic and depressive symptoms and is also effective in the prevention of recurrences, it can be considered as such (CitationBauer and Mitchner 2004; CitationGoodwin and Malhi 2007). Currently, no one treatment adequately fulfills the “ideal” mood stabilizer criteria, although the popular view is that lithium comes closest to doing so (CitationSachs 2005). The emergence of quetiapine, with its bimodal activity against bipolar mania and depression, may qualify as a mood stabilizer in its own right (CitationVieta 2005; CitationSachs 2005).

The defining criteria for a mood stabilizer mentioned earlier omit other desirable characteristics like good tolerability, which tend to become more relevant once efficacy has been established (CitationBauer and Mitchner 2004). Clearly, if a treatment is well tolerated, then adherence, quality of life, and caregiver benefits will also improve. So if the antidepressant efficacy of quetiapine derived from BOLDER and its proven ability in improving manic symptoms from earlier studies place quetiapine monotherapy in a strong position as a potential mood stabilizer, its tolerability profile is favorable enough to permit first line use if syndromal severity is sufficient to justify prescription of an atypical antipsychotic. The low rate of treatment-emergent mania gives quetiapine an obvious advantage over the combination of a mood stabilizer and a traditional antidepressant. Nevertheless, the strong performance of quetiapine in patients with a history of rapid cycling observed in the BOLDER studies does warrant prospective replication before this medication can truly be considered a treatment of choice for this clinically challenging presentation of bipolar disorder. Although longer-term data in bipolar disorder are needed, results of the BOLDER studies are reassuring that a large majority of patients will not gain a meaningful amount of weight during acute-phase therapy. Accompanying quetiapine-induced improvements in quality of sleep, functionality, and health-related quality of life will impact not only the patient, but the family members or caregivers who surround them. Ultimately, caregiver perception and not just patient perception will dictate the success of quetiapine as a mood-stabilizing treatment option. Dedicated studies in this area are awaited with interest.

Conclusions

The BOLDER studies demonstrated that two doses of quetiapine monotherapy – 300 mg and 600 mg – prescribed at bedtime were rapidly effective and generally well tolerated in bipolar depression. The antidepressant efficacy of quetiapine was found in both bipolar I and bipolar II depression and extended to patients with high levels of anxiety as well as those with a history of rapid cycling. Quetiapine was also associated with significant improvements in health-related quality of life, improvements that were intrinsically linked to its antidepressant efficacy. Comparative trials are now needed to help to rank quetiapine therapy among the group of other widely regarded first-line options, and long-term data from controlled studies of patients treated for bipolar depression are also needed to ensure that these effects are durable and that tolerability is acceptable across months or even years of therapy.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the editorial assistance of Eleanor Bull, PhD (PAREXEL MMS). Financial support for this assistance was provided by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP.

References

- AstraZeneca. Seroquel® (quetiapine fumarate) tablets: prescribing information [online] Accessed 2007 April 18. URL: http://www.seroquel.com

- BauerMSMitchnerLWhat is a “mood stabilizer”? An evidence-based responseAm J Psychiatry200416131814702242

- BeckerPMTreatment of sleep dysfunction and psychiatric disordersCurr Treat Options Neurol200683677516901376

- BrownEBMcElroySLKeckPEJrA 7-week, randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination versus lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar I depressionJ Clin Psychiatry20066710253316889444

- BurtonSCStrategies for improving adherence to second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia by increasing ease of useJ Psychiatr Pract2005113697816304505

- CalabreseJRBowdenCLSachsGSA double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study GroupJ Clin Psychiatry199960798810084633

- CalabreseJRKeckPEJrMacfaddenWA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depressionAm J Psychiatry200516213516015994719

- DeppCADavisCEMittalDHealth-related quality of life and functioning of middle-aged and elderly adults with bipolar disorderJ Clin Psychiatry2006672152116566616

- DilsaverSCChenYWSwannACSuicidality, panic disorder and psychosis in bipolar depression, depressive-mania and pure-maniaPsychiatry Res19977347569463838

- EndicottJRajagopalanKMinkwitzMA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I and II depression: improvements in quality of lifeInt Clin Psychopharmacol200722293717159457

- FagioliniAFrankEScottJAMetabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar Disorder Center for PennsylvaniansBipolar Disord200574243016176435

- FrankECyranowskiJMRucciPClinical significance of lifetime panic spectrum symptoms in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorderArch Gen Psychiatry2002599051112365877

- FryeMAKetterTAKimbrellTAA placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disordersJ Clin Psychopharmacol2000206071411106131

- GaudianoBAMillerIWAnxiety disorder comobidity in Bipolar I Disorder: relationship to depression severity and treatment outcomeDepress Anxiety20052171715786484

- GoldbergJFTrumanCJAntidepressant-induced mania: an overview of current controversiesBipolar Disord200354072014636364

- GoodwinGMMalhiGSWhat is a mood stabilizer?Psychol Med2007In Press

- GrunzeHReevaluating therapies for bipolar depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200566Suppl 5172516038598

- HenryCVan den BulkeDBellivierFAnxiety disorders in 318 bipolar patients: prevalence and impact on illness severity and response to mood stabilizerJ Clin Psychiatry200364331512716276

- HirschfeldRMBipolar depression: the real challengeEur Neuropsychopharmacol200414Suppl 2S83815142612

- HirschfeldRMWeislerRHRainesSRQuetiapine in the treatment of anxiety in patients with bipolar I or II depression: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychiatry2006673556216649820

- JuddLLAkiskalHSSchettlerPJThe long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorderArch Gen Psychiatry200259530712044195

- JuddLLAkiskalHSSchettlerPJA prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorderArch Gen Psychiatry200360261912622659

- JuddLLAkiskalHSSchettlerPJPsychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal studyArch Gen Psychiatry20056213223016330720

- KasperSFLiving with bipolar disorderExpert Rev Neurother200446 (Suppl 2)S91516279866

- KeckPEJrBipolar depression: a new role for atypical antipsychotics?Bipolar Disord20057Suppl 4344015948765

- KellerMBPrevalence and impact of comorbid anxiety and bipolar disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200667Suppl 15716426110

- KetterTACalabreseJRStabilization of mood from below versus above baseline in bipolar disorder: a new nomenclatureJ Clin Psychiatry2002631465111874216

- McIntyreRSSoczynskaJKBottasAAnxiety disorders and bipolar disorder: a reviewBipolar Disord200686657617156153

- MichalakEEYathamLNLamRWQuality of life in bipolar disorder: a review of the literatureHealth Qual Life Outcomes200537216288650

- MilevRAbrahamGZaheerJAdd-on quetiapine for bipolar depression: a 12-month open-label trialCan J Psychiatry2006515233016933589

- MitchellPBMalhiGSBipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristicsBipolar Disord20046530915541069

- MitchellPBBallJRBestJAThe management of bipolar disorder in general practiceMed J Aust20061845667016768664

- MullerMJHimmerichHKienzleBDifferentiating moderate and severe depression using the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS)J Affect Disord2003772556014612225

- MurrayCJLopezADRegional patterns of disability-free life expectancy and disability-adjusted life expectancy: global Burden of Disease StudyLancet19973491347529149696

- NemeroffCBUse of atypical antipsychotics in refractory depression and anxietyJ Clin Psychiatry200566Suppl 8132116336032

- OgilvieADMorantNGoodwinGMThe burden on informal caregivers of people with bipolar disorderBipolar Disord20057Suppl 1253215762866

- OstacherMJThe evidence for antidepressant use in bipolar depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200667Suppl 11182117029492

- PerlickDARosenheckRAClarkinJFImpact of family burden and affective response on clinical outcome among patients with bipolar disorderPsychiatr Serv20045510293515345763

- PierreJMExtrapyramidal symptoms with atypical antipsychotics : incidence, prevention and managementDrug Saf20052819120815733025

- PostRMThe impact of bipolar depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200566Suppl 551016038596

- PostRMDenicoffKDLeverichGSMorbidity in 258 bipolar outpatients followed for 1 year with daily prospective ratings on the NIMH life chart methodJ Clin Psychiatry2003646809012823083

- SachsGSWhat is a mood stabilizer?Clin Appr Bipolar Disord200543

- SachsGSNierenbergAACalabreseJREffectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depressionN Engl J Med200735617112217392295

- SchneckCDTreatment of rapid-cycling bipolar disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200667Suppl 1122717029493

- SeemanPAtypical antipsychotics: mechanism of actionCan J Psychiatry200247273811873706

- SimonNMOttoMWWisniewskiSRAnxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD)Am J Psychiatry2004a1612222915569893

- SimonNMOttoMWWeissRDPharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and comorbid conditions: baseline data from STEP-BDJ Clin Psychopharmacol2004b245122015349007

- ThaseMEBipolar depression: issues in diagnosis and treatmentHarv Rev Psychiatry2005132577116251165

- ThaseMEMacfaddenWWeislerRHEfficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the BOLDER II study)J Clin Psychopharmacol200626600917110817

- TohenMVietaECalabreseJEfficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depressionArch Gen Psychiatry20036010798814609883

- TortABSouzaDOLaraDRTheoretical insights into the mechanism of action of atypical antipsychoticsProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200630541816458403

- VietaEMood stabilization in the treatment of bipolar disorder: focus on quetiapineHum Psychopharmacol2005202253615880391

- VietaECalabreseJGoikoleaJfor the BOLDER Study GroupQuetiapine monotherapy in the treatment of patients with bipolar I or II depression and a rapid-cycling disease course: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyBipolar Disord200794132517547587

- VojtaCKinosianBGlickHSelf-reported quality of life across mood states in bipolar disorderCompr Psychiatry200142190511349236

- VornikLAHirschfeldRMBipolar disorder: quality of life and the impact of atypical antipsychoticsAm J Manag Care200511Suppl 9S2758016232010

- YathamLNKennedySHO’DonovanCCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: consensus and controversiesBipolar Disord20057Suppl 356915952957

- YathamLNKennedySHO’DonovanCCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007Bipolar Disord200687213917156158

- ZornbergGLPopeHGJrTreatment of depression in bipolar disorder: new directions for researchJ Clin Psychopharmacol1993133974088120153