Abstract

Purpose:

The risk of visual loss after nonocular surgeries is very low, between 0.2% and 4.5%. According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists, ischemic optic neuropathy has been reported mostly after spinal surgery (54.2%), followed by cardiac surgery and radical neck dissection (13.3%). It may occur in association with some conditions that include systemic hypotension, acute blood loss and hypovolemia.

Case report:

A 46-year-old woman, whose diagnosis was laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, complained of visual loss in her right eye two days after surgery (laryngectomy with bilateral radical neck dissection and left jugular ligature) and one day later in her left eye. The diagnosis was nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

Conclusion:

Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy related to nonocular surgery is usually bilateral and its prognosis is very poor, resulting in blindness or severe visual loss. Although rare, patients should be warned about this complication, which has a profound impact on quality of life, since no therapeutic measure, including correction of hypotension and anemia, seems to improve the prognosis of this complication.

Introduction

Postoperative visual loss (POVL) following general anesthesia during nonocular surgery is a rare, but devastating complication with an estimated incidence of between 0.2% and 4.5% depending on the type of surgery.Citation1 The lesion can occur at the level of the cornea (the most common), retina, optic nerve, or occipital cortex.Citation2

Ischemic optic neuropathies (ION) are now the most frequently reported condition associated with permanent POVL.Citation3 The deterioration of vision generally occurs immediately after surgery and progresses in two or three days. Risk factors include combinations of prolonged surgical times, hypotension, anemia due to blood loss, and prone positioning.Citation4 According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) POVL Registry,Citation5 ION has been reported most frequently after spinal surgery (54.2%), followed by cardiac surgery and radical neck dissection (13.3%). Following cardiac procedures, anterior ION (AION) appears to be more common than posterior ION (PION), whereas following spinal surgery and radical neck dissections, PION is the predominating clinical form.Citation3

AION is an uncommon complication of head and neck surgery, and it has been scarcely reported in the literature.Citation4–Citation7

Case report

A 46-year-old woman with disphony for six months, whose diagnosis was squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx (T1N0M0). She had arterial hypotension (100/70 mm Hg) and a 30-year history of smoking approximately one pack of cigarettes per day. In the preoperative evaluation, all the hematological parameters were normal, and the ASA evaluation was II.

The surgical procedure consisted of a horizontal supraglottic laryngectomy with bilateral radical neck dissection and left jugular ligature. It was performed under general anesthesia, in supine position with hyperextension of the cervical spine, and its duration was approximately six hours. During the surgery, blood pressure was measured every 15 minutes, and it ranged between 100/75 and 75/50 mm Hg, being 90/50 mm Hg for the last 90 minutes of the procedure. Blood loss was moderate, of approximatly 900 cc, and the volume lost by diuresis was 950 cc. Replenishment of volume was performed with 2500 cc of crystalloids and 1000 cc of colloids. Hemoglobin and hematocrit during the operation were 10.2 g/dL (12–16 g/dL) and 29.6% (42%–52%) and upon awaking they were 8.7 g/dL and 24.7% respectively. Recovery from anesthesia was uneventful; during the first five hours after the surgery, blood pressure was monitored, and ranged between 110–115/50–55 mm Hg.

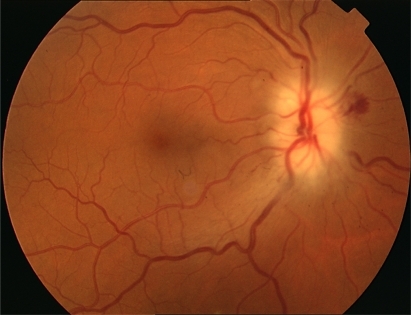

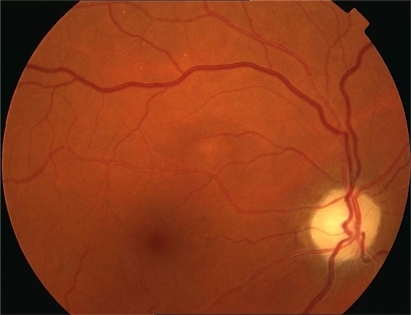

The first day after the surgery, the patient was conscious but sleepy. On the second day, she complained of visual loss in her right eye (RE) and one day later in her left eye (LE). Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was hand movement in the RE and 20/50 in her LE. The pupils were equal in size, but a relative afferent defect was found in the RE. Fundus examination revealed a swollen optic disc with small hemorrhages in the RE and a swollen optic disc in the LE (). The laboratory revealed a sedimentation rate of 113 mm (20–40 mm), protein C 16.97 mg/dL (0.5–2 mg/dL), hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL, and hematocrit 26.6%. Computed tomography (CT) scan of orbit and brain was normal. The diagnosis was nonarteritic AION, and the patient was treated with methylprednisolone 1 g for three days, followed by 1 mg/kg/day for 10 days.

During the following days, several tests were performed. The biopsy of the temporal artery, eco-Doppler of supraaortic trunk and lumbar puncture were normal. The serology for borrelia, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus, and brucella were all negative, as well as the test for autoimmune diseases and hypercoagulability conditions. Magnetic resonance imaging showed numerous hyperintense supratentorial lesions but none of them in the posterior fossa, no lesion enhanced with contrast, and the optic nerves in T2-weighted tomographies showed no hyperintensity. The Neurology department was consulted and they ruled out demyelinating disease, and attributed the lesions to focal ischemia related to tobacco abuse. Two months later the laboratory data were normal.

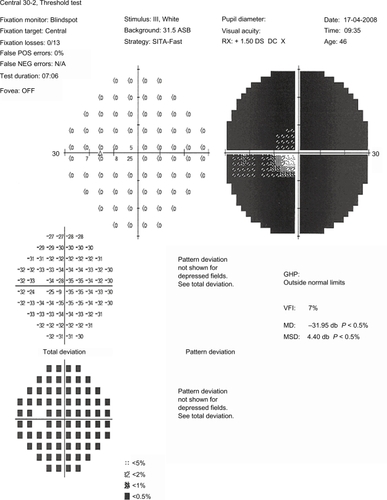

VA improved the second day of treatment, rising to 20/200 in the RE and 15/25 in the LE, but on the following days it decreased again to hand movements in the RE. Standard automated perimetry demonstrated complete loss of visual field in the RE, and extensive damage in the LE, in which only a narrow central island of 5° was preserved (). In the following months, the swollen optic disk and hemorrhages disappeared, evolving towards optic nerve atrophy (), and the VA decreased to light perception in the RE and 20/70 in the LE. One year after surgery, the VA was light perception in the RE and 20/200 in the LE, and the visual fields remained the same.

Discussion

Bilateral visual loss after neck dissection is a rare complication, and it is often due to an ION, usually posterior and less frequently anterior. AION involves both eyes when occurring after surgery, presenting with painless visual loss and pallid disc swelling. Posterior ION, on the other hand, has a normal ocular funduscopic appearance, and it is the most commonly seen form of optic neuropathy following head and neck dissection. Citation7 In almost all cases of perioperative PION, there has been significant perioperative hemorrhage and hypotensionCitation8 and one or both eyes have been involved. Clinicopathological studies have demonstrated an infarction in the intraorbital portion of the optic nerve. Blood flow in the orbit is relatively low compared with blood flow to the eye and other portions of the nerve; therefore, this portion of the nerve may be more vulnerable to ischemia due to hypoperfusion.Citation10

Perioperative AION is less frequent. There are only four cases reported in the literature after radical neck dissection. Citation6,Citation7,Citation11,Citation12 None of them presented severe intraoperative blood loss, although one of the cases presented persistent bleeding in the postoperative period;Citation6 none presented arterial hypertension or diabetes mellitus, the most comon risk factors associated with spontaneous AION.

Spontaneous nonarteritic AION usually involves only one eye and typically occurs in patients aged over 50 years. Small cup-to-disc ratio or absence of excavation and optic disc drusen are ocular risk factors associated with AION.Citation13,Citation14 Arterial hypertension, nocturnal arterial hypotension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, and other cardiovascular disorders, hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, and arteriosclerosis are considered systemic risk factors.Citation14,Citation15 On the other hand, all published cases of perioperative AION have affected both eyes, often occurring in otherwise healthy patients; it is attributed to a combination of hypovolemia, hemodilution, systemic hypotension, anemia, prone position, and pre-existing cardiovascular disease.Citation13

We present a case of bilateral visual loss due to AION after a horizontal supraglottic laryngectomy with bilateral radical neck dissection, in which the patient had preoperative and intraoperative arterial hypotension as the only risk factor. She also had a long history of smoking, a factor also present in the cases reported by Götte and colleaguesCitation6 and by Strome and colleagues.Citation11 In the RNM, our patient had numerous hyperintense supratentorial lesions that were attributed to focal ischemia related to tobacco abuse, possibly indicating a previously disturbed vascular system. Hayreh and colleagues studied the prevalence of smoking among patients with spontaneous AION and found that it was the same as that of the general population, and ruled out smoking as a risk factor for AION.Citation15 However, this study was performed on spontaneous AION, which is, in fact, a different situation from perioperative AION.

Perioperative cases of ION are usually related to a combination of hemodynamic derangements. Perioperative anemia and hypotension can lead to a decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and decreased arterial perfusion pressure. Anemia can result from uncorrected preoperative chronic anemia, intraoperative blood loss and hemodilution, and hypotension from hypovolemia or deliberate hypotension. However, these circumstances are frequent in many surgical procedures, and few patients develop ION, suggesting there must be other associated factors.Citation8 Indeed, a case control analysis of 126,666 procedures in which 17 cases of ION were matched with two control patients on whom the same procedure had been performed showed that there were no hemodynamic variables that differed significantly between the patients with ION and the control cases.Citation16 Another proposed factor is decreased arterial perfusion pressure secondary to increased orbital pressure, which can be caused by jugular vein ligation and by head-down (Trendelenburg) or prone position. This would explain why this complication is more frequent after radical neck dissection or spinal surgery.Citation8 Recently it has been demonstrated that the prone position itself significantly increases intraocular pressure, thereby reducing perfusion pressure in the eye.Citation17 Also, defective autoregulation, which can occur with atherosclerotic disease but also with vasospasm and endogenous or pharmacologic vascoconstriction, would account for patient-specific susceptibility, therefore explaining why so few patients develop this complication.Citation8

In cases with blood loss, it has been proposed that this circumstance, with or without hypertension, causes an increase in renin and endogenous vascoconstrictors secondary to the activation of the sympatethic system and the vasomotor center.Citation18 Another theory proposed by Levin and colleagues is based on the presence of venous congestion. Increased venous pressure, or vasodilatation of the central retinal artery, may compress the central retinal vein and its tributaries within their shared sheath. Venous congestion of the optic nerve parenchyma causes cytotoxic and vasogenic edema, and consequent further compression of the venules feeding the central retinal vein. Venous congestion also causes secondary constriction of the small arterioles via the venoarteriolar response, which may aggravate the ischemia, finally resulting in infarction of the nerve.Citation19

In radical neck dissection, resection of both internal jugular veins leads to increased intracranial venous pressure with resulting decreased perfusion of the nerve.Citation19 The intraocular pressure can also be elevated after this procedure, thereby reducing the perfusion pressure in the optic nerve head even more. Visual loss may be reversible when both internal jugular veins are preserved but permanent when either of them is resected.Citation7

In patients undergoing this type of procedure, possible risk factors should be determined and measures to prevent this complication should be taken. High-risk patients should be positioned so that their heads are at the level of the heart or higher. Their heads should be maintained in a neutral forward position, without neck flexion, extension, lateral flexion or rotation.Citation3 The use of vasopressors to elevate the blood pressure may cause local constriction of small blood vessels, including those supplying the optic nerves.Citation20 Colloids should be used along with crystalloids to maintain intravascular volume in patients who have substantial blood loss.Citation13,Citation21 There is no transfusion threshold that would eliminate the risk of perioperative visual lossCitation18 and blood transfusion carries its own set of risks. The ASA general recommendation is that transfusion is indicated when intraoperative hemoglobin is less than six.Citation21

Perioperative AION is the one of the few situations in which this condition may be treatable, and the vision loss reversible.Citation11,Citation13 Any contributing factors, such as anemia or hypotension, must be aggressively corrected,Citation13 although the diagnosis and management of hypotension and anemia do not seem to improve the prognosis of these patients. Most common treatments in nonarteritic AION are corticoids (oral or intravenous bolus), aspirin, and neuroprotectors, such as brimonidine. Recently, intravitreal triamcinolone and bevacizumab have also been used, though neither has been proved beneficial.Citation12,Citation22 Only systemic corticosteroid therapy may have a beneficial effect. A recent large, prospective study based on 696 eyes with spontaneous nonarteritic AION concluded that eyes treated during the acute phase with systemic corticosteroids (80 mg prednisone daily for two weeks and then tapering down) had a significantly higher probability of improvement in visual acuity and visual field than did the untreated group.Citation23

Head and neck procedures can be considered among the procedures with a risk of POVL. In a large study of more than 500,000 cases (excluding cardiac surgery) in which anesthesia was administered at the Mayo Clinic, two of the four cases of POVL involved radical neck dissection.Citation24 Patients undergoing high-risk procedures should be informed that there is a small, unpredictable risk of perioperative visual loss.Citation3

In conclusion, our report describes a new case of AION in a patient with arterial hypotension as the only risk factor, who suffered a devastating loss of visual acuity (POVL) following a radical neck dissection.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial support or commercial interest in this work.

References

- GilbertMEPostoperative visual loss: a review of the current literatureNeuroophthalmology2008324194199

- RothSThistedRAEricksonJPBlackSSchreiderBDEye injuries after nonocular surgery. A study of 60,965 anaesthetics from 1988 to 1992Anesthesiology1996855102010278916818

- NewmanNJPerioperative visual loss after nonocular surgeriesAm J Ophthalmol2008145460461018358851

- GilbertMESavinoPJSergottRCAnterior ischemic optic neuropathy after rotator cuff surgeryBr J Ophthalmol200690224824916424549

- LeeLARothSPosnerKLThe American Society of Anesthesiologists Postoperative Visual Loss Registry: analysis of 93 spine surgery cases with postoperative visual lossAnesthesiology2006105465265917006060

- GötteKRiedelFKnorzMCHörmannKDelayed anterior ischemic optic neuropathy after neck dissectionArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg2000126222022310680875

- AydinOMemisogluIOzturkMAltintasOAnterior ischemic optic neuropathy after unilateral radical neck dissection: case report and reviewAuris Nasus Larynx200835230831217981414

- BuonoLMForoozanRPerioperative posterior ischemic optic neuropathy: review of the literatureSurv Ophthalmol2005501152615621075

- FentonSFentonJEBrowneMHughesJPConnorMOTimonCIIschaemic optic neuropathy following bilateral neck dissectionJ Laryngol Otol2001115215816011320839

- NawaYJaquesJDMillerNRPalermoRAGreenWRBilateral posterior optic neuropathy after bilateral radical neck dissection and hypotensionGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol199223043013081505758

- StromeSEHillJSBurnstineMABeckJChepehaDBEsclamadoRMAnterior ischemic optic neuropathy following neck dissectionHead Neck19971921481529059874

- WilsonJFFreemanSBBreeneDPAnterior ischemic optic neuropathy causing blindness in the head and neck surgery patientArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg199111711130413061747239

- MathewsMKNonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathyCurr Opin Ophthalmol200516634134516264343

- HayrehSSManagement of non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathyGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol2009247121595160019916247

- HayrehSSJonasJBZimmermanMBNonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and tobacco smokingOphthalmology2007114480480917398323

- HolySETsaiJHMcAllisterRKSmithKHPerioperative ischemic optic neuropathy: a case control analysis of 126,666 surgical procedures at a single institutionAnesthesiology2009110224625319194151

- HuntKBajekalRCalderIMeacherREliahooJAchesonJFChanges in intraocular pressure in anaesthetized prone patientsJ Neurosurg Anesthesiol200416428729015557832

- PazosGALeonardDWBliceJThompsonDHBlindness after bilateral neck dissection: case report and reviewAm J Otolaryngol199920534034510512147

- LevinLADanesh-MeyerHHypothesis: a venous etiology for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathyArch Ophthalmol2008126111582158519001228

- LeeLANothersABSiresBSMcMurrayMKLamAMBlindness in the intensive care unit: possible role for vasopressors?Anesth Analg2005100119219515616077

- Practice Guidelines for blood component therapy: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Blood Component TherapyAnesthesiology19968437327478659805

- HoSFDhar-MunshiSNonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathyCurr Opin Ophthalmol200819646146718854690

- HayrehSSZimmermanMBNon-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: role of systemic corticosteroid therapyGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol200824671029104618404273

- WarnerMEWarnerMAGarrityJAMacKenzieRAWarnerDOThe frequency of perioperative vision lossAnesth Analg20019361417142111726416