Abstract

Aims

To determine which risk factors for blindness were most critical in patients diagnosed with high tension primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) in a large ethnically diverse population managed with a uniform treatment strategy.

Methods

A longitudinal observational study was designed to follow 487 patients (974 eyes) with POAG for an average of 5.5 ± 3.6 years. Detailed ocular and systemic information was collected on each patient and updated every six months. For this study, blindness was defined as visual acuity of 20/200 or worse and/or visual field less than 20° in either eye. Known risk factors were compared between patients with blindness in at least one eye versus nonblind patients.

Results

The patients with blindness had on average: higher intraocular pressure (IOP, mmHg): (24.2 ± 11.2 vs. 22.1 ± 7.7, p = 0.03), wide variation of IOP in the follow-up period (5.9 vs. 4.1 mmHg, p = 0.031), late detection (p = 0.006), poor control of IOP (p < 0.0001), and noncompliance (p < 0.0003). Other known risk factors such as race, age, myopia, family history of glaucoma, history of ocular trauma, hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease, smoking, alcohol abuse, dysthyoidism, and steroid use were not significant.

Conclusions

The most critical factors associated with the development of blindness among our patients were: elevated initial IOP, wide variations and poor control of IOP, late detection of glaucoma, and noncompliance with therapy.

Introduction

The multifactorial and progressive nature of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is well established in regard to optic nerve damage and visual field (VF) loss (CitationWilson et al 1982; CitationO’Brien et al 1991; Hart et al 1997). Over time, 25% to 38% of patients exhibit signs of progression and ultimately blindness in one or both eyes (CitationWilson et al 1982; CitationO’Brien et al 1991; Hart et al 1997). A number of known risk factors associated with progression of vision loss and blindness in glaucoma patients is shown in (CitationReese and McGavic 1942; CitationHarrington 1959; CitationSpaeth 1971; CitationHiller and Kahn 1975; CitationHarbin et al 1976; CitationKolker 1977; CitationDrance et al 1978, Citation1981; CitationPerkins 1978; CitationGrant and Burke 1982; CitationLeske 1983; CitationAnderson 1989; CitationO’ Brien et al 1991; CitationSommer et al 1991a, Citation1991b; CitationAraie et al 1994; CitationQuigley et al 1994; CitationHattenhauer et al 1998; CitationGherghel et al 2000; CitationKing et al 2000; CitationStewart et al 2000; CitationThe AGIS Investigators 2000; CitationKwan et al 2001; CitationOliver et al 2002; CitationChen 2003).

Table 1 Risk factors for blindness in glaucoma

However, it is not clear which of these factors are most important and which are influenced by variables such as fewer patients, short follow up, and ethnically non-diverse patient population. To determine risk factors for progression to blindness, we followed a large ethnically diverse patient population with high tension glaucoma over a long time frame. The primary outcome variable was the average percent of eyes that developed glaucoma-related blindness in either eye. Secondary outcome variables include sustained decrease of vision, progression of the disease, poor control, noncompliance, late detection, and level of intraocular pressure (IOP). Features of patients who developed blindness were compared with those who did not. The underlying hypothesis was that certain risk factors in such a diverse study population were not significant over the long term allowing us to identify the most critical clinical factors.

Materials and methods

Our cohort was selected from the patient population at an academic center, a county hospital, and a Veterans Affairs Hospital.

Legal blindness is defined in the US as visual acuity of 20/200 or worse and/or visual field less than 20° in the better eye (CitationSocial Security Act 2006). Since this study was designed to follow individual eyes, this definition of blindness was modified to refer to either eye rather than the better eye. The diagnosis of POAG included glaucomatous optic nerve cupping with corresponding VF defects, IOP ≥21 mmHg and open irido-corneal angle (CitationKlein et al 1992; CitationDielemans et al 1994). Nine patients were blind in one eye at the start of the study. They were included because adequate long term information on the study variables were available. The exclusion criteria were: normal tension glaucoma (IOP < 21 mmHg), secondary glaucoma, inability to maintain follow up for 3 months, eye conditions such as opaque media, macular degeneration, and vascular accidents that preclude diagnosis of glaucoma, and patients who were unable to perform ocular tests reliably. All eligible patients were examined and treated by the first author or by the eye residents and glaucoma fellows under direct supervision. The study protocol was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards/Ethics Committees of the three clinics and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

In all, 487 eligible patients (974 eyes) with POAG were enrolled in the study. The academic center (231 patients, 462 eyes) is a private patient facility attached to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Parkland Memorial Hospital is a county hospital (98 patients, 196 eyes). The Dallas Veterans Affairs Hospital (158 patients, 316 eyes) is a federal government facility for United States veterans.

Measured continuous and categorical variables at the conclusion of the study are summarized in .

Table 2 Demographics and characteristics of composite patient population: No blindness versus blindness

For this study, VF changes were recorded as stages: 1 = normal; 2 = relative scotoma outside 20°; 3 = absolute scotoma outside 20°; 4 = relative/absolute scotoma within 20°–10°; 5 = relative/absolute scotoma within 10°–5°; 6 = relative/absolute scotoma within 5° in 1–3 quadrants, 7 = relative/absolute scotoma within 5° in all quadrants (CitationJay and Murray 1988). The criteria for VF abnormality on Humphrey program 30-2 full threshold strategy were a cluster of two or more adjacent points of 5-decibels (dB) or greater loss, and at least one of the points showing more than 10 dB loss according to the age corrected total deviation values. Every patient received one or more VF tests yearly. Optic nerve cupping was noted and drawn at baseline exam and at each visit. No photographs were taken. Any progression was flagged and reconfirmed by KSK or the glaucoma fellow. Features of optic disk progression were; progression of C/D ratio by ≥0.2, rim notching and thinning from baseline, and disk hemorrhage. Noncompliance was based on documented nonadherance to therapy/surgery or from two or more missed clinic appointments during the observation period. Poor control of glaucoma was based on the following features: use of three or more medications, requirement of laser or incisional surgery, progression of C/D ratio by ≥0.2, or progression of VF from one stage to the next. Late detection was defined as C/D disparity of ≥0.2 or VF loss of stage ≥3 in one or both eyes at initial presentation.

Categorical variables (such as gender, procedures, medications) of blindness and no-blindness groups were compared with the Fisher’s Exact Test or Chi-square statistics. Continuous variables (such as age, C/D ratio) were compared between groups with two-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests if normality assumptions were not met. Logistic regression models were used to assess multiple risk factors simultaneously. Data management was performed using Microsoft Access 97 and 2000 (Microsoft Corp. Redmond, WA). For statistical analysis, SAS version 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used.

Results

At the end of the study, there were 282 (57.9%) nonblind patients and 205 (42.1%) blind patients. Of the total number of patients, 195 were diagnosed initially at one of the three study clinics. In the blind group, 120 (58.5%) had bilateral blindness while 85 (41.5%) had unilateral blindness. lists the main characteristics of the groups.

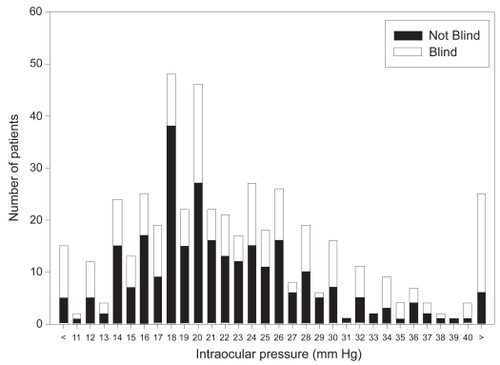

At baseline, the blind group had statistically significant higher IOP than the nonblind group (24.2 vs. 22.1 mmHg; p = 0.03). They also showed wide fluctuations (maximum to minimum IOP) over the course of the study (5.9 mmHg vs. 4.1 mmHg, p = 0.031). The mean IOP for each patient in both groups is shown in .

Figure 1 Prevalence of blindness in relation to intraocular pressure. Blindness was prevalent at all levels of intraocular pressure. 26.3 % of patients were blind at pressures of 17 mmHg or less.

At pressure of 17 mmHg or less, 54 (26.3%) patients were blind. Pressure levels gradually decreased in both groups over time, but the standard deviation of individual IOP was still higher in the blind group (4.8 vs. 2.4 mmHg, p = 0.02).

Blind patients required more laser (43.4%), trabeculectomy (29.3%), and cyclodestruction (4.4%) procedures. Their vision at initial visit was also worse, with 76 (37%) recording vision ≤20/200 and only 93 (45.4%) showing vision of ≥20/40 compared with 261 (92.5%) of the non-blind group. By the last visit, 82 (40%) of blind subjects experienced deterioration of vision and 115 (56%) had dropped to ≤20/200. In comparison, only 36 (12.7%) of the nonblind group showed progression.

In blind individuals, the VF status at initial visit was: mild damage (stage 1 and 2) in 29 (14.2%); moderate damage (stage 3 and 4) in 49 (23.9%); and severe damage (stage 5 to7) in 127 (61.9%). At the final visit the values were 17 (8.3%), 41 (20.0%), and 147 (71.7%), respectively. VF deterioration occurred in 46 (16.3%) of nonblind group and 47 (22.9%) of blind group.

As expected, optic nerve appearance was worse in the blind group at first visit, with 154 (75%) of patients showing C/D of >0.7 compared with 102 (36.2%) in the nonblind group. This figure reached 175 (85.4%) and 132 (46.8%) at the last visit, respectively. Both groups exhibited deterioration of optic nerve features. Similarly, noncompliance, inadequate control and late detection were higher in blind subjects. Baseline IOP, female gender, and baseline VF were significant risk factors for blindness ().

Table 3 Multiple logistic regression analysis of the various variables and their effect on progression to blindness

Other risk factors such as race, age, history of hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease, family history of glaucoma, smoking, alcohol abuse, systemic or topical steroids dysthyroidism, ocular trauma (all variables obtained by history) and myopia, were not significant.

Discussion

Our findings support the widely held belief that IOP is still of paramount importance in management of glaucoma (CitationHarbin et al 1976; CitationKolker 1977; CitationAnderson 1989; CitationO’Brien et al 1991; CitationAraie et al 1994; CitationQuigley et al 1994; CitationGherghel et al 2000; CitationKing et al 2000; CitationStewart et al 2000; CitationThe AGIS Investigators 2000; CitationKwan et al 2001; CitationOliver et al 2002). Blind patients in our study had higher level of initial IOP, more fluctuations in pressure, and were difficult to control. Blindness and progression of glaucoma was evident at all pressure levels (). This finding is in contrast to the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS) where progression was minimal in patients with IOP less than 18 mmHg. The AGIS investigators found that VF progression was less if a patient maintained IOP of less than 18 mmHg at each visit, but their patients had advanced glaucoma based on medical therapy where as this study had patients in all stages of the disease (CitationThe AGIS Investigators 2000). At the final visit 116 (57%) patients had IOP >21 mmHg. Why did so many patients have elevated mean IOP? There may be several explanations. First, some patients become noncompliant or exhibit poor response to therapy. Second, after an eye shows advanced VF loss such as split fixation, there is hesitancy to reduce IOP surgically for fear of “snuffing out” the remaining fibers (CitationKolker 1977). Third, when the visual acuity drops to HM or worse, IOP reduction becomes less of a priority compared with keeping the patient comfortable.

Similar to the findings of CitationKwan and colleagues (2001) our blind patients also required multiple medications and more laser and incisional surgeries. Subjects with blindness also presented with advanced visual acuity loss, VF loss, and optic nerve damage. Therefore, late detection was a significant risk factor. Moreover, a multivariate analysis using logistic regression to model the probability of blindness demonstrated that baseline elevated IOP and advanced VF damage were significant risk factors. Of those who were initially diagnosed with POAG at one of the three study clinics, blindness was detected at the first visit in 21.7%, which was similar to other studies (CitationPerkins 1978; CitationGrant and Burke 1982; CitationKonstas et al 2000). Several investigators have pointed out the role played by advanced VF damage at diagnosis (CitationHarrington 1959; CitationHarbin et al 1976; CitationKolker 1977; CitationQuigley et al 1994; CitationKing et al 2000; CitationOliver et al 2002; CitationChen 2003), degree of VF loss in the worst eye (CitationKing et al 2000), and vascular insufficiency (CitationReese and McGavic 1942; CitationSpaeth 1971; CitationDrance et al 1978; CitationGherghel et al 2000). The progressive nature of POAG was evidenced by VF deterioration. Both noncompliance to treatment and inadequate control were more prevalent in blind patients. The significance of noncompliance with treatment has been stressed by several investigators (CitationDrance et al 1978; CitationKostas et al 2000). One weakness of the study is that the central corneal thickness was not measured because of the unavailability of measuring devices at the three centers. The authors understand the pivotal role central corneal thickness may play in the development and progression of glaucoma (CitationGordon et al 2002).

In conclusion, we followed 487 ethnically diverse patients with high tension POAG in a single metropolitan area and with a uniform management strategy for over 5 years. Risk factors for blindness were mainly pressure-elated: elevated initial IOP, wide variations and poor control of IOP, late detection of glaucoma, and noncompliance with therapy. Other known factors such as older age (CitationQuigley et al 1994; CitationHattenhauer et al 1998; CitationStewart et al 2000), black American (CitationSommer et al 1991a; CitationHiller and Kahn 1975), vascular insufficiency (CitationReese and McGavic 1942; CitationSpaeth 1971; CitationDrance et al 1978; CitationGrant and Burke 1982; CitationGherghel et al 2000), or family history of glaucoma (CitationDrance et al 1978) were not significant. Our results suggest that further studies with larger diverse populations and longer follow are required to verify these findings and to better understand the dynamics of glaucoma progression.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mohamed Mubasher PhD, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Public Health for assistance in statistical analysis. This study was supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AndersonDR1989Glaucoma: The damage caused by pressure. XLVI Edward Jackson Memorial LectureAm J Ophthalmol108485952683792

- AraieMSekineMSuzukiY1994Factors contributing to the progression of visual field damage in eyes with normal-tension glaucomaOphthalmology101144048058289

- ChenPP2003Blindness in patients with treated open angle glaucomaOphthalmology11072133

- DielemansIVingerlingJRWolfsRC1994The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in a population-based study in The Netherlands. The Rotterdam StudyOphthalmology101185157800368

- DranceSMSchulzerMDouglasGR1978Use of discriminate analysis. II. Identification of persons with glaucomatous visual field defectsArch Ophthalmol9615713687196

- DranceSMSchulzerMThomasB1981Multivariate analysis in glaucoma. Use of discriminant analysis in predicting glaucomatous visual field damageArch Ophthalmol991019227236098

- FraserSBunceCWormaldR1999Retrospective analysis of risk factors for late presentation of chronic glaucomaBr J Ophthalmol8324810209429

- GherghelDOrgülSGugletaK2000Relationship between ocular perfusion pressure and retrobulbar blood flow in patients with glaucoma with progressive damageAm J Ophthalmol13059760511078838

- GordonMOBeiserJABrandtJD2002The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucomaArch Ophthalmol1207142012049575

- GrantMBurkeJFJr1982Why do some people go blind from glaucoma?Ophthalmology8999187177577

- HarbinTSPodosSMKolkerAE1976Visual field progression in open-angle glaucoma patients presenting with monocular field lossTrans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otol812537

- HarringtonDO1959The pathogenesis of the glaucoma field. Clinical evidence that circulatory insufficiency in the optic nerve is the primary cause of visual field loss in glaucomaAm J Ophthalmol471778513649857

- HartWJYablonskiMKassMA1979Multivariate analysis of the risk of glaucomatous visual field lossArch Ophthalmol9714558464868

- HattenhauerMGJohnsonDHIngHH1998The probability of blindness from open-angle glaucomaOphthalmology105200914

- HillerRKahnHA1975Blindness from glaucomaAm J Ophthalmol806291155551

- JayJLMurraySB1988Early trabeculectomy versus conventional management in primary open angle glaucomaBr J Ophthalmol7288193067743

- KingAJWThompsonJRRosenthalAR2000Factors influencing the progression to blindness in patients with primary open angle glaucomaInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci41SupplS477

- KleinBEKleinRSponselWE1992Prevalence of glaucoma. The Beaver Dam Eye StudyOphthalmology9914995041454314

- KolkerAE1977Visual prognosis in advanced glaucoma: A comparison of medical and surgical therapy for retention of vision in 101 eyes with advanced glaucomaTrans Am Ophth SocLXXV53955

- KonstasAGPMaskalerisGGratsonidisS2000Compliance and viewpoint of glaucoma patients in GreeceEye14752611116698

- KwanUHKimCSZimmermanB2001Rate of visual field loss and long-term visual outcome in primary open angle glaucomaAm J Ophthalmol132475611438053

- LeskeMC1983The epidemiology of open-angle glaucoma: a reviewAm J Epidemiol118166916349332

- MillerSJHKarserasAG1974Blind registration and glaucoma simplexBr J Ophthalmol58455614412219

- O’BrienCSchwartzBTakamotoT1991Intraocular pressure and the rate of visual field loss in chronic open angle glaucomaAm J Ophthalmol1114915002012152

- OliverJEHattenhauerMGHermanD2002Blindness and Glaucoma: a comparison of patients progressing to blindness from glaucoma with patients maintaining visionAm J Ophthalmol1337647212036667

- PerkinsES1978Blindness from glaucoma and the economics of preventionTrans Ophthalmol Soc UK982935286459

- QuigleyHAEngerCKatzJ1994Risk factors for the development of glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertensionArch Ophthalmol11264498185522

- ReeseABMcGavicJS1942Relation of field contraction to blood pressure in chronic primary glaucomaArch Ophthalmol2784550

- Social Security Act2006Section 1614. Meaning of TermsAccessed December 16, 2006 Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title16b/1614.htm

- SommerATielschJKatzJ1991aRacial differences in the cause-specific prevalence of blindness in East BaltimoreN Engl J Med3251412171922252

- SommerATielschJMKatzJ1991bRelationship between intraocular pressure and primary open angle glaucoma among white and black Americans: the Baltimore Eye SurveyArch Ophthalmol109109051867550

- SpaethGL1971Pathogenesis of visual loss in patients with glaucoma. Pathologic and sociologic considerationsTrans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otol75296317

- StewartWCKolkerAESharpeED2000Factors associated with long-term progression or stability in primary open-angle glaucomaAm J Ophthalmol130274911020404

- The AGIS Investigators2000The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7 The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deteriorationAm J Ophthalmol1304294011024415

- WilsonRWalkerAMDuekerDK1982Risk factors for rate of progression of glaucomatous visual field loss: a computer-based analysisArch Ophthalmol100737416979327