Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is the most common cause of vision loss in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). CMV retinitis afflicted 25% to 42% of AIDS patients in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era, with most vision loss due to macula-involving retinitis or retinal detachment. The introduction of HAART significantly decreased the incidence and severity of CMV retinitis. Optimal treatment of CMV retinitis requires a thorough evaluation of the patient’s immune status and an accurate classification of the retinal lesions. When retinitis is diagnosed, HAART therapy should be started or improved, and anti-CMV therapy with oral valganciclovir, intravenous ganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir should be administered. Selected patients, especially those with zone 1 retinitis, may receive intravitreal drug injections or surgical implantation of a sustained-release ganciclovir reservoir. Effective anti-CMV therapy coupled with HAART significantly decreases the incidence of vision loss and improves patient survival. Immune recovery uveitis and retinal detachments are important causes of moderate to severe loss of vision. Compared with the early years of the AIDS epidemic, the treatment emphasis in the post- HAART era has changed from short-term control of retinitis to long-term preservation of vision. Developing countries face shortages of health care professionals and inadequate supplies of anti-CMV and anti-HIV medications. Intravitreal ganciclovir injections may be the most cost effective strategy to treat CMV retinitis in these areas.

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV), a ubiquitous organism, is the largest of the herpes viruses.Citation1 The prevalence of individuals with evidence of prior CMV infection varies by age, geographic region, and sexual history. Nearly 60% of individuals over the age of six years and more than 80% of those older than 80 years exhibit seropositivity.Citation2 In men infected with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV) and having a history of homosexual behavior, the prevalence of CMV seropositivity exceeds 90%.Citation3

Healthy individuals infected with CMV frequently remain asymptomatic, although some develop an influenza-like syndrome characterized by fever, chills, malaise, myalgias, and arthralgias. People with normal immune systems rarely develop long-term sequelae. Similar to other herpes viruses, CMV then enters a latent state, continually suppressed by cell-mediated immunity. CMV remains latent unless the patient suffers from a significant local (regional corticosteroid therapy) or systemic immunodeficiency, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), pharmacologic immunosuppression to prevent allograft organ transplant rejection, local and systemic corticosteroid therapy, or an autoimmune condition such as Wegener’s granulomatosis. Recurrent CMV infections may cause colitis, encephalitis, or retinitis (which account for 75% to 85% of CMV end-organ disease).Citation4

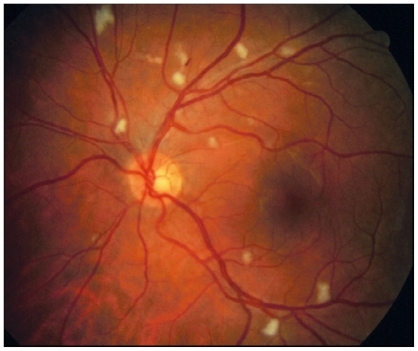

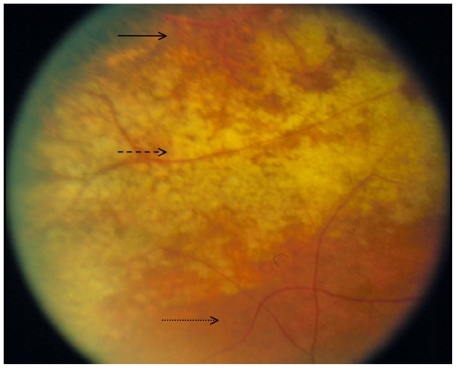

The AIDS era began in 1981 when a group of five homosexual men developed unusual opportunistic infections (pneumocystis pneumonia, candidiasis, and CMV infections) due to severe immunodeficiency.Citation5,Citation6 The ocular abnormalities in these patients included a non-infectious occlusive retinal microvasculopathy (), and progressive, necrotizing retinitis ().Citation7

Figure 2 Retinitis is progressing from top to bottom: solid line points to area of necrotic retina following retinitis; dashed line points to area of active retinitis; dotted line points to area of normal retina.

During the first 14 years of the AIDS era, retinal abnormalities were identified as the most significant ocular findings and the major cause of blindness in affected patients. Between 25% and 42% of AIDS patients developed CMV retinitis, the most common reason for severe vision loss.Citation8–Citation10 Retinitis occurred in advanced AIDS patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts of <50 cells/μL.Citation11,Citation12 Among patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts <50 cells/μL the rate of CMV infection rate was 0.2 cases/person-year (PY).Citation12

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996, originally defined as two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) combined with a protease inhibitor (PI), and in 2004 expanded by the DHHS/Kaiser panel to include a PI, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, one of the NRTIs (abacavir or tenofovir), an integrase inhibitor (eg, raltegravir), or an entry inhibitor (eg, maraviroc or enfuvirtide),Citation13 became a watershed event in the treatment of HIV-infected patients. HAART decreased the mortality rate among HIV-infected patients, and significantly decreased the incidence and altered the natural history of many opportunistic infections, particularly CMV retinitis. Although most large centers have observed an 80% decrease in the incidence of CMV retinitis, it remains the most common reason for vision loss in AIDS patients.Citation14 The incidence of CMV retinitis in the post-HAART era is estimated to be at most 5.6 cases/100 PY.Citation15

Despite the changes in incidence and severity of retinitis caused by HAART, the ophthalmoscopic appearance of CMV retinitis does not appear to have changed. The Longitudinal Study of the Ocular Complications of AIDS showed that the ocular findings in patients with newly diagnosed CMV retinitis in the post-HAART era resembled those prior to the introduction of HAART.Citation16 However, differences in disease location, severity, and patient immune status have been reported.

On average, newly diagnosed CMV retinitis patients have CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 50 cells/μL, but these values cover a broader range than in the pre-HAART era. This may indicate a selective loss of immunity against CMV not reflected by total CD4+ T-lymphocyte count, or an improvement in laboratory values before the restoration of protective immunity. Up to 69% of newly diagnosed cases are due to HAART failure, as measured by either persistently low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts or high HIV RNA blood levels.Citation17 Each of these factors independently predicts CMV reactivation. HAART failure patients more frequently present with asymptomatic, bilateral retinitis, better visual acuity, less zone 1 disease, and lesser lesion opacification. Since lesion opacification is believed to correlate with viral activity, these patients have lower levels of viral replication.Citation18 Milder disease also correlates with better visual acuity and fewer symptoms. Since many patients have asymptomatic disease, physicians should consider regular ophthalmic screening examinations of at-risk patients.

Although the diagnosis of CMV retinitis indicates that these patients have HAART failure, the milder ocular disease suggests that HAART has a beneficial effect on modulating disease severity and vision loss. HAART-treated patients have a lower incidence of retinal detachment,Citation19 disease progression and second eye involvement.Citation20 Despite this, HAART patients with CMV retinitis have an increased mortality rate, especially those with lower CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts.Citation21

Intravenous therapy

Ganciclovir

Ganciclovir (Cytovene®, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Nutley, New Jersey, approved in 1989), the first anti-CMV drug, became available on a compassionate use basis in 1984. It is a synthetic acyclic nucleoside analog of 2′-deoxyguanosine. Following uptake by CMV-infected human cells, ganciclovir is monophosphorylated by the enzyme UL97 (the rate-limiting step) and then triphosphorylated to its active form by activated kinases of the host cell. The triphosphate form interrupts viral DNA synthesis by competing with deoxyguanosine triphosphate.

To achieve high tissue concentrations during induction, ganciclovir is administered twice daily at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Since maintenance therapy is anticipated to continue for weeks to months in most patients, a peripherally-inserted central catheter (PIC) line is usually placed to allow atraumatic, repeated intravenous access. Catheter-related bacterial or fungal sepsis (occurring in 12% of patients) remains an important complication.Citation22

Ganciclovir excretion occurs by glomerular filtration and active tubular excretion via the kidneysCitation23 and is directly related to creatinine clearance.Citation24,Citation25 Patients with mild (CLCR ≤ 0 mL/min) to severe (CLCR ≤ 10 mL/min) renal impairment require lower ganciclovir doses because the areas under the curve are increased by 1.8- to 15-fold. Dose adjustments appropriate to renal function are given in .

Table 1 Recommended induction and maintenance dosing of IV ganciclovir adjusted for renal functionCitation63

Ganciclovir causes hematologic abnormalities (neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia) and probable long term reproductive toxicity. Women of reproductive age receiving ganciclovir need to be counseled about birth control. Patients with low neutrophil counts must discontinue ganciclovir or augment neutrophil synthesis with colony stimulating factors such as filgrastim (Neupogen®). Weekly subcutaneous injections usually raise neutrophil counts to acceptable levels (>1000 cells/mL). Since both ganciclovir and zidovudine are similarly capable of causing leukopenia, patients receiving both drugs frequently require reduced doses.

Viral resistance to ganciclovir occurs most commonly due to mutations in the viral protein kinase UL97 gene, which is responsible for monophosphorylation of ganciclovir. The incidence of viral resistance increases with the duration of therapy from 2.2% at three months to 15.3% at 18 months.Citation26 Not surprisingly, viral resistance is associated with larger areas of retinitis and increased loss of vision.Citation27

Foscarnet

Foscarnet (Foscavir®, AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, Delaware, approved in 1991) is a pyrophosphate analog. It interferes with the binding of the diphosphate to the viral DNA polymerase of Herpes simplex, Varicella zoster, cytomegalovirus, and HIV.Citation28

Daily induction dosing of foscarnet consists of 180 mg/kg (usually given as 90 mg/kg twice daily) followed by maintenance therapy of 90 mg/kg once daily. Similar to ganciclovir, foscavir treatment usually lasts weeks to months, thereby requiring a PIC line.

Foscarnet is highly nephrotoxic and must be administered carefully to patients with renal disease. Patients require adequate hydration and frequent monitoring of creatinine levels. Viral resistance has been mapped to point mutations in the pol gene UL54. Cross-resistance between ganciclovir and foscarnet has been observed in numerous viral isolates with both phenotypic and genotypic resistance.Citation28 Foscarnet is generally considered a second line therapy that is often administered to patients with ganciclovir-resistant viral strains or dose-limiting neutropenia.Citation29

Cidofovir

Cidofovir (Vistide®, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Foster City, California, approved in 1996) is an acyclic nucleoside phosphonate. Following intracellular phosphorylation to the diphosphate form by host kinases, cidofovir targets the viral DNA polymerase by acting as a chain terminator. After incorporation at the 3′-end of the viral DNA chain, it terminates CMV DNA synthesis. Cidofovir is a broad spectrum antiviral agent with activity against CMV, acyclovir-resistant HSV infections, genital warts, laryngeal and cutaneous papillomatous lesions, molluscum contagiosum lesions, adenovirus infections, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).Citation30

The active form of cidofovir exhibits remarkable intracellular stability (half-life > 24 hours) thus allowing for infrequent dosing. Induction dosing consists of 5 mg/kg once weekly for two weeks, followed by 5 mg/kg every other week during maintenance. Mutations of the viral DNA polymerase UL54 gene result in viral resistance to cidofovir as well as foscarnet and ganciclovir.

Severe renal toxicity is the major limitation to long-term cidofovir therapy. Patients must be adequately hydrated and pretreated with oral probenicid to protect against kidney failure. Due to the risk of renal toxicity and ocular hypotony, cidofovir is generally considered a second line therapy. Because of its association with immune recovery uveitis, cidofovir should not be used if immune recovery is expected.

Oral therapy

Ganciclovir

Oral ganciclovir was introduced in 1994 in an attempt to lower costs, eliminate the inconvenience of daily intravenous drug injections, reduce the risk of catheter-related sepsis, and improve patient quality of life.Citation31 Maximum oral doses were 3 gm per day (12 capsules taken on a three times daily schedule), but since the bioavailability was only 6% to 9%, patients could not achieve plasma concentrations sufficient for induction therapy.Citation22 The primary indication for oral ganciclovir was prevention of contralateral retinitis and non-ocular CMV disease in patients receiving intraocular therapy.Citation32 When oral valganciclovir with its high bioavailability and convenient once-daily dosing was introduced, production and distribution of oral ganciclovir was discontinued.

Valganciclovir

Valganciclovir (Valcyte®, Roche Pharmaceuticals, approved in 2000) is an orally administered monovalyl ester prodrug of ganciclovir. After absorption from the gut, valganciclovir undergoes rapid hydrolysis to ganciclovir in both the intestinal mucosa and liver. Ingesting valganciclovir with a high fat meal increases the area under the plasma concentration-time curve by 24% to 30%, without prolonging the time to peak concentration.Citation33

Because of its high bioavailability (60%) valganciclovir can be used for both induction and maintenance therapy.Citation34 Induction therapy, typically 900 mg once daily for 2–3 weeks, results in serum ganciclovir levels 1.7 times those achievable with oral ganciclovir and comparable with those achieved with intravenous ganciclovir. Maintenance therapy is usually 450 mg once daily. As with intravenous ganciclovir, dosing of valganciclovir should be decreased in patients with renal dysfunction ().

Table 2 Recommended induction and maintenance dosing of oral valganciclovir adjusted for renal functionCitation49

Oral valganciclovir is well tolerated, with the most common side effects being hematologic (neutropenia [16%], anemia [11%]), and gastrointestinal (diarrhea [13%], nausea [8%], and vomiting [4%]).Citation22 Drug interaction studies with valganciclovir have not been performed, but since it undergoes rapid conversion to ganciclovir, interactions are likely to be the same as with ganciclovir. Oral valganciclovir therapy is associated with a low incidence of viral resistance.

Intravitreal therapy

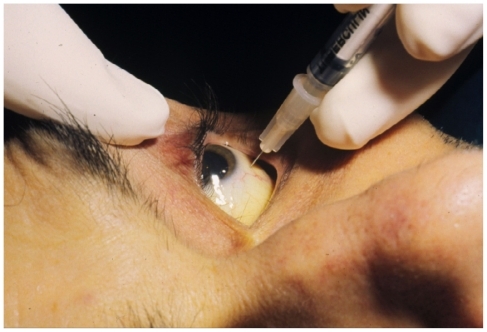

During the 1980s and 1990s intravitreal drug injections were given to patients who were intolerant of or refused systemic therapy. Several non-controlled studies show that most patients respond to induction therapy with each of the available drugs. Anti-CMV drugs can be injected in the office with topical anesthesia and sterile preparation of the eye with povidone-iodine solution (). Although post-injection antibiotic drops have not been proven to lessen the incidence of endophthalmitis, most surgeons recommend broad spectrum treatment for 3–4 days.

Intravitreal injections of ganciclovir result in high retinal tissue concentrations without systemic bone marrow suppression. Since ganciclovir is supplied as a highly soluble powder, a wide range of concentrations can be formulated. Repeated doses ranging from 200 μg/0.1 mL to 2000 μg/0.1 mL have been injected into eyes without observable retinal toxicity.Citation35,Citation36 An accidently administered dose of 6 mg caused no harm, but 40 mg resulted in retinal damage. Twice-weekly injections are given during the induction phase, followed by weekly injections during maintenance. Time to disease progression has been estimated to be eight weeks.Citation37

Few noncontrolled studies of intravitreal foscarnet injections have been published.Citation38–Citation40 In the largest series, 11 patients experienced successful induction therapy (six injections of 2400 μg given at 72-hour intervals) followed by weekly maintenance injections. Reactivation of the retinitis occurred in 33.3% of patients within 20 weeks. Since foscarnet is distributed as a solution, higher drug concentrations cannot be made.

Cidofovir has a narrow therapeutic index for intravitreal injections, unlike ganciclovir which has a wide therapeutic index. Despite the manufacturer’s warning against intravitreal administration,Citation41 cidofovir has been injected into a small number of eyes. Cidofovir injections (20 μg every 5–6 weeks) have been effective as induction therapy. With a mean followup of 15 weeks, 7.5% of patients (all previously treated with intravenous ganciclovir, foscarnet or both) experienced progression of their retinitis. Post-injection uveitis occurs frequently (17%; 41% in those not receiving prophylaxis with oral probenecid). Many patients experience a transient reduction in intraocular pressure and 3% develop irreversible hypotony with severe vision loss.Citation42 A double-masked, randomized trial of three cidofovir doses (5 μg, 10 μg, and 15 μg) was prematurely terminated due to high incidences of iritis (87%) and hypotony (16%), and low efficacy.Citation43 Intravitreal administration of cidofovir is no longer recommended.

Fomiversin (Vitravene®, Novartis Ophthalmics AG, Bulach, Switzerland, and Isis Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Carlsbad, California, approved in 1998) is an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide that hybridizes with and blocks expression of CMV mRNA. Two intravitreal injections every other week were followed by monthly maintenance injections. The major complication was mild uveitis which was treated with topical corticosteroids. Production and distribution of fomivirsen has been discontinued.

The efficacy of intravitreal injections must be weighed against several inherent disadvantages. Weekly injections during the maintenance phase may be inconvenient for both the patient and physician. Although generally safe, intravitreal injections may be complicated by vitreous hemorrhages (3%), retinal detachments (8%), and endophthalmitis. Since CMV retinitis arises from active blood-borne disease, patients receiving intravitreal injections remain at risk for contralateral eye disease (11%–30%), non-ocular end-organ infections (16%), and increased mortality.Citation44–Citation47 Most experts recommend that patients treated with intravitreal injections also receive systemic therapy with oral valganciclovir (most frequently) or one of the intravenous drugs.

Ganciclovir implant

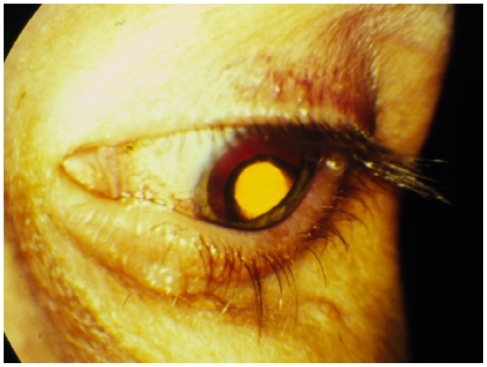

The efficacy and safety of intraocular therapy, combined with the absence of systemic toxicity, spurred the development of the sustained-release ganciclovir implant (Vitrasert®, Bausch and Lomb, Inc., San Dimas, California, approved in 1996). This polyvinyl alcohol/ethylene vinyl acetate device releases ganciclovir from a 4.5 mg capsule at a rate of 1 μg/hr for up to nine months. In a randomized study, the implant extended the mean time to retinitis progression well beyond that achieved with intravenous therapy (221 days vs 76 days).Citation48

The reservoir is surgically implanted through a pars plana incision and secured with a non-absorbable transscleral suture (). A transient decrease in visual acuity occurs during the first two weeks following implantation. The risk of retinal detachment rises in the early post-operative period but decreases in the long term due to superior control of the retinitis. Since retinitis usually recurs when the ganciclovir implant empties, many surgeons either replace the implant after 32 weeks or, to avoid reopening the previous incisions, place an additional implant through a different pars plana site.

Treatment strategies

Improved patient survival with HAART has shifted the focus of anti-CMV treatment from short-term suppression of disease to long-term maintenance of vision. This means combining immune system reconstitution with effective short- or long-term anti-CMV therapy.

For patients not taking antiretroviral medications, one must first consider starting HAART; for HAART-failure patients, changing medications should be considered. Some infectious disease specialists will consider delaying HAART in patients with opportunistic infections to minimize the risk of immune recovery syndromes (immune recovery uveitis in patients with CMV retinitis).

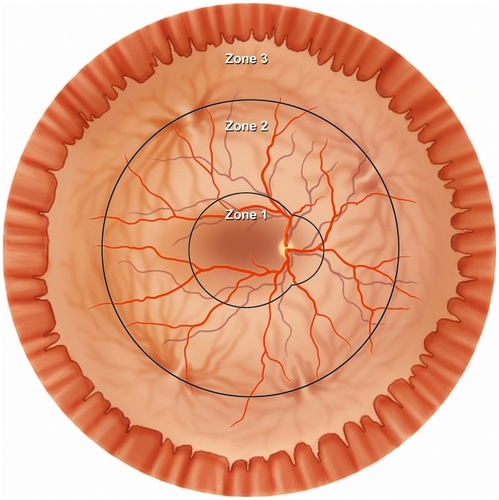

Treatment of CMV retinitis should be individualized, taking into account the size and location of the retinitis, the patient’s experience with HAART, and the risk of treatment-related complications. The location of infected retina determines the risk for vision loss; posterior retinitis threatens the macula and optic nerve; and anterior retinitis increases the risk of retinal detachment. The ocular fundus is divided into three zones; zone 1 encloses the area within 1500 μm of the nerve or 3000 μm of the fovea, zone 2 includes the area outside of zone 1 but posterior to the equator (as defined by the vortex veins), and zone 3 includes the peripheral retina between the equator and the ora serrata ().Citation8

Figure 5 Diagram of the retina shows the three anatomic zones used for classification of CMV retinitis.

Since CMV retinitis patients have a high risk of death that can be decreased by anti-CMV therapy, all patients, if possible, should receive systemic medication as part of the treatment regimen.Citation21,Citation46

To suppress viral replication rapidly and minimize systemic complications (usually neutropenia and renal toxicity), early protocols developed the two-phase treatment strategy. A two- to three-week period of frequent, high-dose drug administration to stop viral replication (induction phase) was followed by a continuous period of lower-dose therapy to suppress viral activity for as long as possible (maintenance phase). Induction therapy for CMV retinitis is usually with one of four available drugs, ie, ganciclovir, foscavir, cidofovir (all intravenous), oral valganciclovir, or surgical placement of the intravitreal ganciclovir implant. The choice of anti-CMV therapy is usually based on efficacy and tolerability profiles, pharmacologic considerations, and quality of life issues ().Citation49 Comparison studies (intravenous ganciclovir with oral ganciclovir or intravenous foscarnetCitation25,Citation50,Citation51 or cidofovirCitation52) have failed to show significant differences between drug choices. Throughout the course of treatment, patients and physicians must remember that these drugs suppress CMV replication but do not eliminate the virus from the eye. Unless the patient experiences adequate reconstitution of the immune system, retinitis treatment must be continued indefinitely.

Table 3 Summary of dosing, adverse events, advantages and disadvantages of the available four systemic anti-CMV drugsCitation49

Episodes of relapse (also termed progression), defined as centrifugal advancement of the lesion borders, were expected with intravenous therapy. Early relapses were attributed to inadequate ocular drug concentrations,Citation53,Citation54 whereas later relapses were increasingly associated with acquired drug resistance.Citation55–Citation57 Unfortunately, the pace of relapses appeared to accelerate with the duration of treatment. Relapses were retreated with induction phase dosing, and this cycle was repeated until the patient’s death. Except for therapy with the intravitreal ganciclovir implant, this strategy continues to be used.

For most patients, valganciclovir is the drug of choice, due to its lower cost and lower complication rate, as well as convenient oral administration. Induction therapy (900 mg once daily) has been shown to be as effective as intravenous ganciclovir (5 mg/kg twice daily).Citation58 This regimen arrests CMV progression in >90% of eyes and achieves a satisfactory clinical response in 72% of patients. Median time to progression is 160 days, compared with 125 days in patients receiving intravenous ganciclovir induction therapy followed by oral ganciclovir maintenance. Among the 10% of patients who did not respond favorably to induction, 71% progressed within the first two weeks. The relative risk of progression in the valganciclovir group (compared with the ganciclovir group) was 0.9 (95% CI: 0.58, 1.38). The incidence of retinal detachment was 19% in each group. Systemic CMV suppression, as measured by serum, blood, and urine cultures, and PCR assay, occurred in both groups.

Each available anti-CMV drug regimen has associated disadvantages. Intravenous ganciclovir and foscarnet require indwelling catheters which increase cost, create inconvenience, and expose patients to the risk of secondary sepsis. Daily ganciclovir infusions last one hour, but each of three daily foscarnet infusions lasts two hours. The infrequent dosing of cidofovir does not require an indwelling catheter; however, the high risk of dose-related, potentially irreversible nephrotoxicity (up to 50%) requires pre-treatment with probenicid and adequate hydration.Citation59 Nephrotoxicity and uveitis (seen in 10% of patients receiving the intravenous formulation) limit the use of cidofovir.Citation60

The ganciclovir implant more effectively delays retinitis progression, but surgical implantation carries significant operative cost and comorbidities, such as endophthalmitis and retinal detachment.Citation61 For HAART-naïve patients who may be expected to recover immunity against CMV, the eight months of continuous drug release may not be necessary. However, for patients with sight-threatening zone 1 retinitis, where rapid disease inactivation is critical to maintain vision, the implant, in combination with oral therapy, may be the best initial therapeutic choice ().Citation32 While surgery is being planned, intravitreal injections of ganciclovir can quickly establish high intraocular antiviral levels to prevent disease progression.Citation62 Since immune recovery is the most important factor for long-term CMV control, patients whose HAART therapy cannot be improved should be considered for implant surgery. Unless patients with the ganciclovir implant also receive systemic anti-CMV therapy, they are at high risk of developing both contralateral retinitis and extraocular CMV disease. Compared with intravenous therapy, oral valganciclovir equally prevents and treats non-ocular CMV disease. Valganciclovir has been shown to prevent the development of systemic CMV disease in 83% of patients and contralateral retinitis in 94% of cases.Citation22

Table 4 Suggested treatment strategy for patients with newly diagnosed CMV retinitisCitation62

The introduction of valganciclovir rapidly changed preferred treatment patterns. A retrospective analysis of insured patients in the US evaluated anti-CMV treatment from 1997 to 2002. The use of intraocular therapy changed minimally (13.3% to 15.8%) whereas the use of oral drugs increased from 9.6% to 43.4%, at the expense of intravenous therapy, which decreased from 77.1% to 40.8%. This may be due in part to the lower cost of oral valganciclovir ($69 US/day vs $163 US/day for the intravenous preparation).Citation63

The rate of CMV reactivation has fallen from 3.0 cases/PY (pre-HAART) to 0.1 case/PY (post-HAART), with most of the improvement attributed to immune recovery.Citation19 Reactivation of CMV retinitis can usually be successfully retreated with induction therapy and anecdotal reports suggest that repeat induction therapy in HAART-treated patients may require less aggressive therapy than in the pre- HAART era.Citation64 Recurrent disease always raises the concern of drug resistance, but the prevalence of drug-resistant CMV has fallen (from 28% to 9%) since the introduction of HAART.Citation65 Patients with drug-resistant infections can be difficult to treat and may require therapy with foscarnet or cidofovir.

Reconstitution of the immune system following initiation of HAART can be sufficient to suppress CMV retinitis in some patients. More commonly, immune recovery allows for the discontinuation of anti-CMV therapy without rebound CMV reactivation in many patients. Long term studies show that patients with non-sight-threatening, quiescent retinitis for six months, and reconstitution of the immune system, may be considered for discontinuation of anti-CMV medications. The decision to stop CMV therapy depends upon many factors, including rising CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts, falling systemic HIV loads (preferably to undetectable), duration of HAART (at least three months), and inactivity of CMV lesions. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that the CD4+ T-lymphocyte be at least 100–150 cells/μL for 3–6 months before CMV therapy is discontinued.Citation66 However, most authors require more robust evidence of immune reconstitution (ie, CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts >200 cells/μL; 100-fold drop in HIV blood levels) before discontinuing therapy.Citation67,Citation68 Contradicting studies have reported successful discontinuation of therapy despite HIV blood levels exceeding 30,000 copies/mL.Citation64

Once anti-CMV therapy has been discontinued, patients need close monitoring of their ophthalmologic status with attention to falling CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts, and rising HIV blood loads. The risk of CMV reactivation is estimated to be 0.02 events/PY.Citation64,Citation68 Correlation exists between rising systemic CMV Ag titers and DNA levels, and reactivation of retinitis, but the predictive value of these tests remains insufficient to warrant routine screening.Citation69 Serial ophthalmologic examinations at three-monthly intervals are frequently recommended, although supportive data for this practice does not exist. At-risk patients should be counseled to test themselves frequently for changes in visual acuity and peripheral fields; changes should be reported to their ophthalmologist immediately. Stopping anti-CMV therapy incurs reduced costs, decreased pill load, fewer complications, and better compliance with antiretroviral therapy.

Immune recovery many not occur for up to three months after institution of HAART, making patients susceptible to opportunistic infections (including CMV retinitis) during this period. An estimated 8% to 15% of CMV retinitis patients contracted their disease after apparently successful HAART-induced immune reconstitution.Citation70 Generalized expansion of CD4+ T-lymphocyte populations, but not the clones with specific anti-CMV memory, may allow retinitis to develop.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis against CMV disease in at- risk AIDS patients is clinically neither beneficialCitation71 nor cost effective.Citation72 A small study failed to prevent end-organ disease when anti-CMV therapy was given to HAART-treated patients with viremia (Wohl unpublished data 2006).

Unseen in the pre-HAART era, the immune-reconstitution inflammatory syndromes frequently complicate HAART therapy. Although these disorders have been given several names, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) has become the most widely accepted general term,Citation73 with immune recovery uveitis (IRU) given to ocular inflammation. IRU occurs when the recovered immune system recognizes and then reacts to a large intraretinal CMV antigen load.

IRIS occurs in 15% to 25% of HIV-positive patients receiving HAART, with the highest incidence between eight and 16 weeks after initiation of treatment.Citation74 Patients with low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts (fewer than 50 cells/μL),Citation75 large areas of CMV retinitis (25% to 30% of the retina),Citation16 and a history of cidofovir useCitation74 have the greatest risk of IRU. For patients who have had CMV retinitis, IRU occurs in 9.6% of those with immune recovery.Citation16 The rate of visual impairment in HAART-treated patients is 0.1 cases/eye year (EY) and the rate of blindness is 0.06 cases/EY. The rate of visual impairment in IRU patients is 0.17 cases/EY.Citation76 Although unusual, patients with partial immune reconstitution may develop IRU in the presence of persistent CMV retinitis.Citation70

Immune recovery uveitis usually coincides with a rapid reconstitution of the immune system, as measured by an increase in the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. A small percentage of patients, however, develop IRU without a CD4+ Tlymphocyte increase, suggesting that improved immunity against CMV may occur by some as yet unrecognized mechanism.Citation76,Citation77 Affected patients have undetectable CMV DNA in blood and vitreous specimens. The clinical spectrum of IRU ranges from asymptomatic vitritis, through mild transient vitritis, to a persistent uveitis with floaters, decreased vision, cystoid macular edema (12.3 × increased risk) and epiretinal membrane (3.7 × increased risk) formation.Citation78,Citation79 Uveitis is believed to be directed toward residual CMV DNA at the edge of previous retinitis.Citation80 Infrequent complications include neovascularization, disc edema, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, cataract and posterior synechiae. Citation76 Although some patients experience severe vision loss (20/200 or worse), most patients have visual acuities between 20/50 and 20/200.

HAART-treated patients diagnosed with IRU need to have other inflammatory conditions (syphilis, herpetic retinitis, drug toxicity) excluded. PCR testing of intraocular fluids may help rule out infectious etiologies.Citation81

In attempting to avoid IRU, some investigators recommend delaying HAART therapy until CMV retinitis is controlled. A small study reported a decreased rate of IRU when HAART was delayed until after induction therapy for CMV. This delay strategy carries significant risk given that infected patients have a high risk of death during the period immediately following diagnosis of CMV retinitis.Citation82

Treatment of IRU depends upon the severity of the inflammation and the responsiveness of the complications. Mild inflammation with macular edema can sometimes be treated effectively with topical and periocular corticosteroidsCitation83,Citation84 but other eyes are refractory to treatment.Citation85 Intravitreal corticosteroids have successfully treated eyes refractory to less aggressive treatment but, in addition to the usual complications of cataracts and glaucoma, reactivation of retinitis may occur.Citation85,Citation86 The sustained-release intravitreal fluocinolone implant has successfully resolved inflammation and edema but has also caused reactivation of retinitis.Citation87,Citation88 To prevent CMV reactivation following corticosteroid treatment, some authors recommend restarting anti-CMV therapy.Citation89 Surgery for cystoid macular edema, cataract, vitritis, and epiretinal membranes has yielded mixed results.Citation87

Retinal detachments affected up to 40% of CMV-infected eyes (0.5 cases/PY) in the pre-HAART era. Post-HAART, the overall rate of detachment has fallen to 0.06 cases/PY, but remains high in patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 50 cells/μL.Citation19 Since many of these eyes had large areas of necrotic retina with persistent vitreoretinal traction, standard reattachment techniques (scleral buckle, vitrectomy with fluid/air exchange) were frequently unsuccessful. Vitrectomy with silicone oil tamponade quickly became the surgical procedure of choice. Despite successful reattachment, patients frequently lost vision due to cataract, aniseikonia, and for unknown reasons. Although silicone oil removal can improve visual acuity, it carries a 53% risk of retinal redetachment.

Now that patients are living much longer, and retinal detachment repair with silicone oil carries a poor visual prognosis, surgeons should consider attempting initial repair with air tamponade with or without scleral buckle.Citation90 Patients for whom this approach is most appropriate may be those with peripheral disease for which posterior delimiting laser photocoagulation can be safely placed.Citation91

CMV in developing countries

The previous sections of this review discuss the optimal treatment of CMV retinitis while assuming that sufficient resources (HAART, anti-CMV drugs, health personnel, access to care) are available to affected patients. Although developed countries usually provide these resources, underdeveloped countries frequently lack one or more components. Consequently, patients may receive “substandard” care, with a higher likelihood of vision loss and decreased life expectancy.

At present 90% of HIV-infected people live in the developing countries of sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Significant regional variability exists in the prevalence of opportunistic infections, with high rates of tuberculosis, cryptococcus and pneumocystis pneumonia.

An estimated 5% to 25% of AIDS patients in developing countries will develop blindness.Citation92 The incidence of CMV retinitis in India varies from 2% in HAART-treated patients (with another 6% of patients developing IRU)Citation93 to 20% (35% of which were active infection; 65% were healed lesions), with the majority of these receiving HAART.Citation94 Biswas et al reported that 17% of HAART-naïve patients had CMV retinitisCitation95 and eight years later the same authors reported that the incidence had fallen to 5.7%.Citation96 Up to 25% of patients with a history of CMV retinitis develop IRU.Citation94

The incidence of CMV retinitis in sub-Saharan Africa varies from 0% to 19.6%.Citation97–Citation101 In Malawi the prevalence of anterior segment AIDS-related eye disease was 13%, whereas retinitis was seen in only 1% of patients.Citation102 None of 56 patients in a Gambian study had retinitis.Citation103 CMV retinitis developed in 0.2% of HAART-naïve patients in EthiopiaCitation99 but 19.8% of HAART-treated patients in Thailand.Citation101 The low prevalence of HIV-related eye disease in Africa may be due to patients dying before developing ocular opportunistic infections.Citation92,Citation104 The low incidences observed in Africa differ from those reported in India, suggesting that the diagnosis of retinitis may depend more upon access to medical care than on racial or geographic differences.Citation105 Regional variations in the prevalence of opportunistic organisms and government-sponsored HAART distribution programs may also account for the lower incidence of CMV retinitis in some areas.

The experience at one Indian referral center illustrates the consequences of health funding shortfalls facing developing countries. Ten of 23 newly diagnosed CMV retinitis patients received two weeks of induction therapy (intravenous ganciclovir) followed by one week of maintenance. Limited resources prevented the continued administration of systemic maintenance therapy, but three patients received intravitreal ganciclovir injections.Citation95

Indian cost and income data from 2000 illustrates the financial challenges in treating CMV retinitis patients: intravenous ganciclovir therapy costs $714/month, anti- HIV therapy costs $547/month, with the average per capita income being only $380/month. Working within these financial constraints, intravitreal ganciclovir injections emerge as the most cost-effective, available method of controlling CMV retinitis. Intravitreal ganciclovir injections have been successfully used at selected centers in South Africa, Botswana,Citation97 and Thailand,Citation101 and intravitreal foscarnet has been used for both induction and maintenance therapy.Citation106 A Thai economic model suggested that CMV retinitis treatment with intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir would be cost-effective, whereas intravitreal ganciclovir injections would be cost-effective for patients not receiving HAART.Citation107 Although injections fail to prevent non-ocular CMV infection and contralateral CMV retinitis, and may not extend life expectancy, they allow patients the opportunity to maintain useful vision.

Effective intravitreal therapy regimens require adequately trained ophthalmic professionals to perform early screening eye examinations, regular followup examinations and intravitreal injections. Unfortunately, many developing countries are deficient in trained ophthalmic personnel. Perhaps the challenges involved in treating CMV retinitis were best summarized by Shah: “The availability and cost of drugs such as ganciclovir and followup for ocular diseases such as CMV retinitis limit the visual outcome in these patients.”

Many patients fail to return for followup examinations after being diagnosed with CMV retinitis.Citation96 Although some authors recommend ophthalmic screenings of at-risk patients,Citation108 limited resources make such programs difficult to implement. HIV-infected patients in India do not receive routine ophthalmologic examinations and are seen only if they become symptomatic.Citation96 The incidence of CMV retinitis, particularly in patients with asymptomatic zone 3 disease, may be underestimated because of inadequate ophthalmic screening programs. Additionally, inadequate followup of patients with diagnosed CMV retinitis patients may doom them to blindness because of unchecked disease progression.

HAART generally decreases the incidence of CMV retinitis and, through reconstitution of the immune system, establishes long term remission. In developing countries this requires government and non-government agencies to provide medical care and anti-HIV medications at affordable prices.Citation109 The governments of India and Thailand now provide anti-HIV medications free of charge to all infected patients.Citation101,Citation110 Increasing availability of HAART in countries such as India may change the incidence of CMV retinitis due to several factors, including longer survival, improved immunologic status, and increased incidence of immune recovery uveitis.Citation93 However, despite the availability of HAART, AIDS patients in low-income countries have higher mortality rates than those in high-income countries.Citation111

Future

Currently available anti-CMV drugs have unfavorable toxicity profiles, and foscarnet and cidofovir have insufficient bioavailability to be administered orally. A need remains for an effective oral agent with minimal toxicity.

The CMV epidemic associated with AIDS drove the development of anti-CMV medications during the 1980s and 1990s but the introduction of HAART, with the resultant dramatic decrease in CMV retinitis, served to slow drug development. However, during the same period, advances in organ procurement, surgical instrumentation and techniques, and anti-rejection drugs have enabled organ transplant programs to flourish. Organ recipients are at high risk of non-ocular CMV, which is now called the “troll” of organ transplant patients. Their need for chronic CMV suppression has served to re-stimulate drug development. Future drug development may, therefore, depend upon success in organ recipient trials.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- KedharSRJabsDACytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapyHerpes200714667118371289

- StarasSASDollardSCRadfordKWSeroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988–1994Clin Infect Dis2006431143115117029132

- DrewWLMitzLMinerRCPrevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in homosexual malesJ Infect Dis19811431881926260871

- GallantJEMooreRDRichmanDDIncidence and natural history of cytomegalovirus disease in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease treated with zidovudine. The Zidovudine Epidemiology Study GroupJ Infect Dis1992166122312271358986

- GottliebMSSchroffRSchankerHMPneumocystis carinii pneumonia and mucosal candidiasis in previously healthy homosexual men: Evidence of a new acquired cellular immunodeficiencyN Engl J Med1981305142514316272109

- MasurHMichelisMAGreeneJBAn outbreak of community-acquired Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: Initial manifestation of cellular immune dysfunctionN Engl J Med1981305143114386975437

- HollandGNGottliebMSYeeRDOcular disorders associated with a new severe acquired cellular immunodeficiency syndromeAm J Ophthalmol1982933934026280503

- HollandGNBuhlesWCMastreBKaplanHJA controlled retrospective study of ganciclovir treatment for cytomegalovirus retinopathy. Use of a standardized system for the assessment of disease outcome. UCLA CMV Retinopathy Study GroupArch Ophthalmol1989107175917662556989

- Studies of Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group in collaboration with the AIDS Clinical Trials GroupFoscarnet-Ganciclovir Cytomegalovirus Retinitis Trial: 5. Clinical features of cytomegalovirus retinitis at diagnosisAm J Ophthalmol19971241411579262538

- BloomJNPalestineAGThe diagnosis of cytomegalovirus retinitisAnn Intern Med19881099639692848436

- KuppermanBDPettyJGRichmanDDCorrelation between CD4+ counts and prevalence of cytomegalovirus retinitis and human immunodeficiency virus-related noninfectious retinal vasculopathy in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndromeAm J Ophthalmol19931155755828098183

- PertelPHirschtickREPhairJRisk of developing cytomegalovirus retinitis in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virusJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr19925106910741357151

- Definition of HAART Available from: http://statepiaps.jhsph.edu/wihs/Invest-info/Def-haart.pdfAccessed on January 10, 2010

- SkiestDJCytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)Am J Med Sci199931731833510334120

- JabsDAVan NattaMLHolbrookJTLongitudinal study of the ocular complications of AIDS. 1. Ocular diagnoses at enrollmentOphthalmology200711478078617258320

- JabsDAVan NattaMLHolbrookJTLongitudinal study of the ocular complications of AIDS. 2. Ocular examination results at enrollmentOphthalmology200711478779317210182

- HollandGNVaudauxJDShiramizuKMCharacteristics of untreated AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis. II. Findings in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (1997 to 2000)Am J Ophthalmol2008145122218154751

- JabsDAvan NattaMLKempenJHCharacteristics of patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapyAm J Ophthalmol2002133486111755839

- JabsDAvan NattaMLThorneJECourse of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: 2. Second eye involvement and retinal detachmentOphthalmology20041112232223915582079

- JabsDAvan NattaMLThorneJECourse of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: 1. Retinitis progressionOphthalmology20041112224223115582078

- JabsDAHolbrookJTvan NattaMLRisk factors for mortality in patients with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapyOphthalmology200511277177915878056

- LalezariJPFriedbergDNBissetJHigh dose oral ganciclovir treatment for cytomegalovirus retinitisJ Clin Virol200224677711744430

- NobleSFauldsDGanciclovir: An update of its use in the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipientsDrugs1998561151469664203

- FauldsDHeelRCGanciclovir: A review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in cytomegalovirus infectionsDrugs1990395976382161731

- MarkhamAFauldsDGanciclovir: An update of its therapeutic use in cytomegalovirus infectionDrugs1994484554847527763

- BoivinGGilbertCGaudreauARate of emergence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) mutations in leukocytes of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome who are receiving valganciclovir as induction and maintenance therapy for CMV retinitisJ Infect Dis20011841598160211740736

- JabsDAMartinBKFormanMSCytomegalovirus resistance to ganciclovir and clinical outcomes of patients with cytomegalovirus retinitisAm J Ophthalmol2003135263412504693

- BironKKAntiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseasesAntiviral Res20067115416316765457

- RazonableRREmeryVCManagement of CMV infection and disease in transplant patients [Consensus article IHMF management recommendations]Herpes200411778615960905

- De ClerqEAntiviral drugs in current clinical useJ Clin Virol20043011513315125867

- DrewWLIvesDLalezariJPOral ganciclovir as maintenance treatment for cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDSN Engl J Med19953336156207637721

- MartinDFKuppermanBDWolitzRAOral ganciclovir for patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis treated with a ganciclovir implantN Engl J Med19993401063107010194235

- BrownFBankenLSaywellKPharmacokinetics of valganciclovir and ganciclovir following multiple oral dosages of valganciclovir in HIV- and CMV-seropositive volunteersClin Pharmacokinet19993716717610496303

- JungDDorrASingle-dose pharmacokinetics of valganciclovir in HIV-and CMV-seropositive subjectsJ Clin Pharmacol19993980080410434231

- HenryKCantrillHFletcherCUse of intravitreal ganciclovir (dihydroxy propoxymethyl guanine) for cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with AIDSAm J Ophthalmol198710317233026186

- YoungSHMorletNHenrySHigh dose intravitreal ganciclovir in the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitisMed J Aust19921573703731333036

- Cochereau-MassinILehoangPLautier-FrauMEfficacy and tolerance of intravitreal ganciclovir in cytomegalovirus retinitis in acquired immune deficiency syndromeOphthalmology199198134813531658703

- Diaz-LlopisMChipontESanchezIntravitreal foscarnet for cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndromeAm J Ophthalmol19921147427471334376

- LiebermanRMOrellanaJMeltonRCEfficacy of intravitreous foscarnet in a patient with AIDSN Engl J Med20043308688698114855

- Diaz-LlopisMEspanaEMunozGHigh dose intravitreal foscarnet in the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDSBr J Ophthalmol1994781201248123619

- Package insert. Vistide (cidofovir, Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, September 1996).

- RahhalFMArevaloJFMunguiaDIntravitreal cidofovir for the maintenance treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitisOphthalmology1996103107810838684797

- KuppermanBWolitzRStaggRA Phase II randomized, double-masked study of intraocular cidofovir for relapsing cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS [Abstract]Presented at the Vitreous Society Annual MeetingCancun, MexicoDecember 8–12, 1996

- JabsDAOcular manifestations of HIV infectionTrans Am Ophthalmol Soc1995936236838719695

- KempenJHJabsDAWilsonLAIncidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in second eyes of patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome and unilateral CMV retinitisAm J Ophthalmol20051391028103415953432

- KempenJHJabsDAWilsonLAMortality risk for patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis and acquired immune deficiency syndromeClin Infect Dis2003371365137314583871

- JabsDAHolbrookJTvan NattaMLRisk factors for mortality in patients with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapyOphthalmology200511277177915878056

- MuschDCMartinDFGordonJFTreatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis with a sustained-release ganciclovir implantN Engl J Med199733783909211677

- CvetkovicRSWellingtonKValganciclovir: A review of its use in the management of CMV infection and disease in immunocompromised patientsDrugs20056585987815819597

- The Studies of Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group in collaboration with the AIDS Clinical Trials GroupCombination foscarnet and ganciclovir therapy vs monotherapy for the treatment of relapsed cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS: The Cytomegalovirus retreatment trialArch Ophthalmol199611423338540847

- JacobsonMADrug therapy: treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndromeN Engl J Med19973371051149211681

- The Studies of Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group in collaboration with the AIDS Clinical Trials GroupThe ganciclovir implant plus oral ganciclovir versus parenteral cidofovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: The ganciclovir cidofovir cytomegalovirus retinitis trialAm J Ophthalmol200113145746711292409

- KuppermanBDQuicenoJIFlores-AguilarMIntravitreal ganciclovir concentration after intravenous administration in AIDS patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis: implications for therapyJ Infect Dis1993168150615098245536

- AraveloJFGonzalezCCapparelliEVIntravitreous and plasma concentrations of ganciclovir and foscarnet after intravenous therapy in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitisJ Infect Dis19951729519567561215

- JabsDAEngerCDunnJPFormanMCytomegalovirus retinitis and viral resistance: ganciclovir resistance. CMV Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study GroupJ Infect Dis19981777707739498461

- JabsDAEngerCDunnJPFormanMIncidence of foscarnet resistance and cidofovir resistance in patients treated for cytomegalovirus retinitis. The Cytomegalovirus Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study GroupAntimicrob Agents Chemother199842224022449736542

- WeinbergAJabsDAChouSMutations conferring foscarnet resistance in a cohort of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and cytomegalovirus retinitisJ Infect Dis200318777778412599051

- MartinDFSierra-MaderoJWalmsleySA controlled trial of valganciclovir as induction therapy for cytomegalovirus retinitisN Engl J Med20023461119112611948271

- PloskerGLNobleSCidofovir: A review of its use in cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDSDrugs19995832534510473024

- WalmsleySTsengAComparative tolerability of therapies for cytomegalovirus therapyDrug Saf19992120322410487398

- AcharyaNYoungLSustained-release drug implants for the treatment of intraocular diseaseInt Ophthalmol Clin200444333915211175

- JabsDAAIDS and Ophthalmology, 2008Arch Ophthalmol20081261143114618695113

- MahadeviaPJGeboKAPettitKThe epidemiology, treatment patterns, and costs of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the post-HAART era among a national managed-care populationJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20043697297715220705

- WalmsleySLRaboudJAngelJBLong-term follow-up of a cohort of HIV-infected patients who discontinued maintenance therapy for cytomegalovirus retinitisHIV Clin Trials200671916632459

- MartinBKRicksMOFormanMSJabsDAChange over time in incidence of ganciclovir resistance in patients with cytomegalovirus retinitisClin Infect Dis2007441001100817342657

- BensonCAKaplanJEMasurHTreating opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of AmericaMMWR Recomm Rep200453111215841069

- HollandGNDiscussion of MacDonald JC, Karavellas MP, Torriani FJ, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy-related immune recovery in AIDS patients with cytomegalovirus retinitisOphthalmology200010787783310811078

- WohlDAKendallMAOwensSThe safety of discontinuation of maintenance therapy for cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis and incidence of immune recovery uveitis following potent antiretroviral therapyHIV Clin Trials2005613614616192248

- JabsDAMartinBKFormanMSRicksMOCytomegalovirus (CMV) blood DNA load, CMV retinitis progression, and occurrence of resistant CMV in patients with CMV retinitisJ Infect Dis200519264064916028133

- HollandGNAIDS and Ophthalmology: The first quarter centuryAm J Ophthalmol200814539740818282490

- SkiestDJCytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)Am J Med Sci199931731833510334120

- KempenJHFrickKDJabsDAIncremental cost effectiveness of prophylaxis for cytomegalovirus disease in patients with AIDSPharmacoeconnomics20011911991208

- MurdochDMVenterWDVan RieAFeldmanCImmune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS): Review of common infectious manifestations and treatment optionsAIDS Research and Therapy20074917488505

- KempenJHMinYIFreemanWRRisk of immune recovery uveitis in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitisOphthalmology200611368469416581429

- HirschHHKaufmannGSendiPImmune reconstitution in HIV infected patientsClin Infect Dis2004381159116615095223

- ThorneJEJabsDAKempenJHIncidence of and risk factors for visual acuity loss among patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapyOphthalmology200611314231440

- FrenchMAThe immunopathogenesis of mycobacterial immune restoration diseaseLancet Infect Dis2006646146216870523

- KaravellasMPPlummerDJMacDonaldJCIncidence of immune recovery vitritis in cytomegalovirus retinitis patients following institution of successful highly active antiretroviral therapyJ Infectious Dis19991796977009952380

- KempenJHMinYIFreemanWRRisk of immunity recovery uveitis in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitisOphthalmology200611368469416581429

- SchrierRDSongMKSmithILIntraocular viral and immune pathogenesis of immune recovery uveitis in patients with healed cytomegalovirus retinitisRetina20062616516916467672

- WestenegACRothovaADe BoerJHGroot-MijnesJDInfectious uveitis in immunocompromised patients and the diagnostic value of polymerase chain reaction and Goldmann-Witmer coefficient in aqueous analysisAm J Ophthalmol200714478178517707328

- Ortega-LarroceaGEspinosaEReyes-TeranGLower incidence and severity of cytomegalovirus-associated immune recovery uveitis in HIV-infected patients with delayed highly active antiretroviral therapyAIDS20051973573815821403

- HendersonHWMitchellSMTreatment of immune recovery vitritis with local steroidsBr J Ophthalmol19998354054510216051

- KaravellasMPAzenSPMacdonaldCImmune recovery uveitis and uveitis in AIDS: Clinical predictors, sequellae and treatment outcomeRetina2001211911217922

- El-BradeyMChengLSongMLong term results of treatment of macular complications in eyes with immune recovery uveitis using a graded treatment approachRetina20042437638215187659

- HendersonHWMitchellSMTreatment of immune recovery vitritis with local steroidsBr J Ophthalmol19998354054510216051

- RothovaAInflammatory cystoid macular oedemaCurrent Opinion Ophthalmol200718487492

- Ufret-VincentyRLSinghRPLowderCYKaiserPKCytomegalovirus retinitis after fluocinolone acetonide implantAm J Ophthalmol200714333433517258523

- MorrisonVLKozakILaBreeLDIntravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for the treatment of immune recovery uveitis macular edemaOphthalmology200711433433917270681

- CanzanoJCMorseLSWendelRTSurgical repair of cytomegalovirus-related retinal detachment without silicone oil in patients with AIDSRetina19991927428010458290

- DavisJRemoving silicone oil from eyes with cytomegalovirus retinitisAm J Ophthalmol200514090090216310469

- KestelynPThe epidemiology of CMV retinitis in AfricaOcul Immunol Inflamm1999717317710611725

- ShahSUKerkarSPPazareAREvaluation of ocular manifestations and blindness in HIV/AIDS patients on HAART in a tertiary care hospital in western IndiaBr J Ophthalmol200993889018952644

- GharaiSVenkateshPGargSOphthalmic manifestations of HIV infections in India in the era of HAART: Analysis of 100 consecutive patients evaluated at a tertiary eye care center in IndiaOphthalmic Epidemiol200815426427118780260

- BiswasJMadhavanHNGeorgeAEOcular lesions associated with HIV infection in India: A series of 100 consecutive patients evaluated at a referral centerAm J Ophthalmol200012991510653406

- BiswasPNSahaBGhoshSOphthalmic manifestations in people living with HIV attending a tertiary care centre of Eastern IndiaJ Indian Med Assoc200810629229418839634

- NkomazanaOTshitswanaDOcular complications of HIV infection in sub-Sahara AfricaCurr HIV/AIDS Rep2008512012518627660

- NwosuNNHIV/AIDS in ophthalmic patients: The Guinness Eye Centre Onitsha experienceNiger Postgrad Med J200815242718408779

- T/GiorgisAMelkaGMariamAOphthalmic manifestation of aids in Armed Forces General Teaching Hospital, Addis AbabaEthiop Med J20074532733418326342

- OsahonAlOnunuANOcular disorders in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, NigeriaNiger J Clin Pract200710428328618293635

- ManosuthiWChaovavanichATansuphaswakifulSIncidence and risk factors of major opportunistic infections after initiation of antiretroviral therapy among advanced HIV-infected patients in a resource-limited settingJ Infect20075546446917714788

- ShafranSDSingerJZarownyDPA comparison of two regimens for the treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex bacteremia in AIDS: Rifabutin, ethambutol, and clarithromycin versus rifampin, ethambutol, clofazimine, and ciprofloxacin. Canadian HIV Trials Network Protocol 010 Study GroupN Engl J Med19963353773838676931

- NicholsCWMycobacterium avium complex infection, rifabutin, and uveitis – is there a connection?Clin Infect Dis199622S43S478785256

- CochereauIMlika-CabanneNGodinaudPAIDS related eye disease in Burundi, AfricaBr J Ophthalmol19998333934210365044

- WengTNVersacePOcular association of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy and the global perspectiveClin Exp Ophthalmol200533317329

- AusayakhunSWatananifornSNgamtiphakornSPrasitsilpJIntravitreal foscarnet for cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDSJ Med Assoc Thai20058810310715960227

- TeerawattananonKIewsakulSYenjitrCEconomic evaluation of treatment administration strategies of ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV/AIDS patients in Thailand: a simulation studyPharmacoeconomics20072541342817488139

- ChiouSHLiuCYHsuWMOphthalmic findings in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndromeJ Microbiol Immunol Infect200033454810806964

- DeCockKMLucasSBLucasSClinical research, prophylaxis, therapy, and care for HIV disease in AfricaAm J Public Health199383138513898214225

- National AIDS Control Organization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of IndiaProgramme implementation guidelines for phased scale up of access to antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV/AIDSMumbai, IndiaNational AIDS Control Organization2004

- BraitsteinPBrinkhofMWDabisFMortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countriesLancet200636781782416530575