Abstract

Objective:

This paper, the second of two, represents a theoretical framework for interventions related to loss by death of someone close, or chronic pain. This work is based on our previous understanding where grief is considered an integrated experience which involves movements on several continua.

Methods:

We have performed a comparison between two interventions dealing with grief and chronic pain using different designs. Interrelated experiences and processes were identified.

Results:

Life phenomena like grief and loss caused by death and chronic pain, seem to have many qualities in common and may overlap each other. A common core containing emptiness, vulnerability and exhaustion is identified.

Discussion:

Despite advances in research and thinking in recent years, several issues related to grief caused by death or chronic pain remain a challenge in clinical settings and research. When preparing interventions, we must pay attention to the relearning process, the common core and the interplay between these bodily expressions.

Conclusion:

We believe there is a value in future research and practice to consider losses caused by death and chronic pain, together as well as separately. Our comprehensive approach indicates that understanding the processes involved in one sort of grief may help understand the processes involved in the other.

Keywords:

Introduction

This is a follow-up study based on our previous article,Citation1 which constitutes a theoretical framework for understanding grief related to loss caused by death of someone close, and loss caused by chronic pain, as unique experiences. Common for these phenomena is that grief influences the existential parts of life and is described as a reconstructive process following such suffering.Citation2 The examination of grief caused by death and chronic pain reveals many similarities. In this context, the subjective meaning the patient expresses related to his or her loss, will represent a starting point in grief work. This understanding indicates the fact that support to people who suffer grief caused by death or chronic pain, should focus on grief as a specific type of experience taking a phenomenological perspective.Citation1 Here a movement from relearning the world and adaptation becomes essential in grief work independent of its cause.Citation1 Previous intervention studies performed by the present authors related to loss and grief caused by death and chronic pain,Citation3–Citation5 have several common features including a structured group approach, homework and writing as an important tool following several distinct steps. The main focus is on thoughts and emotions to induce behavioral changes. In one study,Citation3,Citation4 writing was introduced as homework and provided the platform for the following group meetings. In the other study,Citation5 writing was conducted in grief writing groups and using diaries.

Loss caused by death is naturally connected to grief. However, loss caused by chronic pain may also lead to grief experiences. These losses have the potential to elicit existential difficulties such as lack of control and reduced predictability about life. Such changes may diminish the person’s well-being, hope for the future and ability to cope.Citation6 Loss as a life experience may concern something irrevocable and the feelings connected to what is lost. As such, grief may be related to several losses caused by chronic pain, like loss of health, loss of work or social relations.Citation7 This is also consistent with ParkesCitation8 who discovered parallel processes of grieving whether the loss was caused by losing a limb or through the death of someone close. Such losses are naturally integrated in the human experience, but sometimes they unfold in ways which are difficult to define. Dealing with loss and grief refers to an individual experience and some central aspects of grief processing and grief work incorporate issues such as expressing grief, gaining an awareness of the loss, retaining and sustaining some ties to what is lost, acknowledgement through new insights and an adjustment to the new life situation.Citation5 Walker et alCitation9 suggest that material losses as well as perceptions of loss are prominent issues for those seeking help from pain clinics for their pain problems. Whitley-ReedCitation10 reports that grief therapy is effective in reducing pain and depression in a group of chronic pain sufferers. Those who suffer grief related to loss by death may also benefit from group approaches where cognitive, emotional and behavioral components are highlighted.Citation5 Independent of the cause, the grief experience may involve the whole life situation and represents a huge challenge for the sufferers as well as the health care workers.

Aim

Based on the authors’ previous studiesCitation1,Citation3–Citation5 we now want to extend the discussion in order to deepen our understanding of the relationship between chronic pain, loss and grief. Furthermore, we will highlight important elements when developing integrated programs in chronic pain- and grief management.

Theoretical framework

Our previous integrated programs dealing with grief related to loss by death and nonmalignant chronic painCitation1 contributes to an extended understanding of these phenomena. In addition, two previous programs for interventionsCitation3–Citation5 based on a group approach, will now be introduced as a basis for our integrated program. The summaries of the organization and the main differences in our programs are presented (), and each program will also be described in more detail as a foundation for discussion (Appendix A).

Table 1 Organization of the grief and pain management program

Group approach

Group approaches are used in our previous studiesCitation3–Citation5 and have many advantages in the treatment of grief and loss caused by death or chronic pain. Firstly, acccording to Keefe et alCitation11 a group provides a setting in which patients can be in touch with others who have similar problems. Secondly, group participation can help patients gain a better understanding of pain and grief and the role of their own behavior, thoughts and feelings regarding the perception of their situation. Thirdly, patients can be taught effective coping skills and how these skills can be integrated in daily life.Citation11 YalomCitation12 emphasizes several important supportive factors such as hope, acceptance, universality and altruism that can be successful when conducting groups. In addition, self-revelation factors encompass self-disclosure and the expression of emotions, while psychological work factors include self-understanding and interpersonal learning. Lastly, the learning from others factors, like modeling seem to be important and incorporate vicarious learning, guidance and education.Citation12 In all such group approaches, LintonCitation13 notes that the content of the group approach and how the therapy is practiced are good predictors of success or failure.

Cognitive behavioral theory (CBT)

The pain management programmeCitation3,Citation4 is based on a cognitive behavioral approach. In recent decades, the multiple disturbing effects of chronic pain on patients’ physical and psychosocial functioning have been widely recognized in rehabilitation. Biomedical treatment only partly alleviates these consequences of chronic pain.Citation14 As a result, there has been considerable interest in psychological treatment models, which address the complex interaction of biological symptoms and psychosocial factors.Citation14 Major aims of CBT, within the broad framework of learning theory, are to improve quality of life, coping skills and physical functioning. CBT for chronic pain involves a variety of interventions that share three basic components: emphasizing the patients’ ability to help themselves rather than depending on therapists; Interest in the nature and modification of patients’ thoughts, feelings and behavior; Behavior therapy procedures promoting change (such as homework, relaxation, social skill training, and physical activity).Citation15

Writing theory

A major component of the grief management program is process oriented writing theory. Here it is fundamental that there is a dynamic relationship between thought and language, and thus an active use of language stimulates and promotes thought activity.Citation5,Citation16–Citation20 Writing is a creative developmental process. In this process thoughts emerges and the writer may experience increased awareness and knowledge.Citation16,Citation18–Citation20 Writing one’s own ideas opens a channel to get acquainted with one’s own thinking potential.Citation21 Studies indicate that to write and form a story, is to reflect on events and contributes to self understanding and new insight.Citation5,Citation23,Citation24 Creative writing in the grief work becomes a tool for acknowledgement and knowledge. The writing process helps the writer to identify new relationships as well as to reveal any lack of coherence and understanding.Citation5,Citation18,Citation19 Elements from process oriented writing theory is central to the construction in writing program where grief work consists of handling thoughts and feelings.

Chronic pain management program

The intervention was active, time limited and structured. The multidisciplinary team consisted of a physician, a physiotherapist, a psychologist and two nurses. The groups were conducted according to a structured protocol, and two supervisors were involved in each group. Self-help educational material (tools) included in the program was mainly based on the pedagogical framework of BrattbergCitation25 and the pain dimensions in the Gate Control Theory of pain.Citation26 The major contribution of this model is an emphasis on the central nervous system and psychological variables in the pain perception process. Each session began by giving a brief summary of the last group meeting, followed by sharing positive experiences over the past week. A review of the group members’ home practice provided a platform for the supervised dialogue. This program, including follow-up after 6 and 12 months, consisted of three parts: supervised dialogue, physical activity and education. Each session lasted for 5 hours including a lunch break.

Grief management program

The various assignments or subjects in the writing program, make the different aspects of the grief process more tangible. The leaders of the grief writing group were deacons with experience of grief work groups. The participants were divided into two groups: one group consisted of individuals who had experienced the loss of a spouse or a partner. The other group consisted of individuals who had lost a parent or a sibling. Throughout the program the writing was done along two parallel tracks: writing in a grief writing group and writing at home in a diary. At each meeting of the writing groups, the writing was centered on a subject or an assignment. The types of writing that were encouraged as processing tools, were free writing forms and focused writing. Conversation before the writing commenced was encouraged in order to introduce and focus on the theme of the day. Conversation after writing in the group was also encouraged, giving each participant the opportunity to converse about thoughts and feelings related to the writing.

In each writing group meeting the participants were encouraged to write a diary at home. The writing in these diaries was based on personal wishes or initiatives. In addition, homework with writing based on specific topics was introduced. The writing program lasted for 5 months during which group meetings were held every 2 weeks during the initial 3 months, with one meeting in each of the following months, a total of 10 meetings.

Methods

Several methodological steps were followed in this comparative study using an open qualitative approach:

Step 1: A process of reflection and discussion focused on content, organization, similarities and differences related to grief and loss in our previous implemented pain and grief management programs (, Appendix A).

Step 2: We discussed and reflected on how the theoretical framework in the first two-part article could be extended by focusing on the movements between “the relearning and adaptation” processCitation1 and the qualitative data related to loss and grief.Citation3–Citation5

Step 3: A thematic analysis was carried out on the transcribed qualitative data from our intervention studies, by searching for common as well as distinctive categories related to experiences of loss and grief caused by death and chronic pain.

Step 4: An analytic reflection and abstraction was performed searching for common sub-themes and main theme ().

Step 5: A search was made for a model to clarify the connections between the sub-themes related to loss, grief and chronic pain and a main theme ().

Step 6: Based on the previous analytic steps, suggestions for a new integrated framework was discussed.

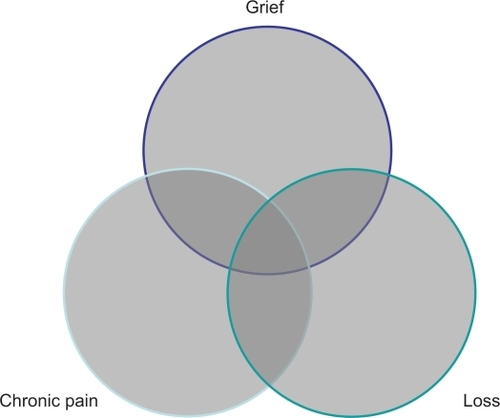

Figure 1 Results illustrating the overlapping experiences between chronic pain, loss and grief. The common core is characterized as an existential vacuum containing emptiness, vulnerability and exhaustion.

Table 2 Categories, sub-themes and themes from the thematic analysis of the transcripts from the grief and chronic pain management groups

Results

The discussion revealed several common main components within each program such as systematic writing and homework combined with group dialogue, and a supervised dialogue where thoughts and feelings related to what was lost were conceptualized (). Both studies had empirical data which resulted from writing individually in groups and notes from homework tasks. Categorized experiences which were expressed in the grief groups were different related losses, painful bereavement, loneliness, painful and depressive thoughts and feelings, anger, despair and sadness. In the pain groups, the experiences were different related losses, painful bereavement, loneliness, painful and depressive thoughts and feelings, frustration, anger and resignation (). Common sub-themes for these categories were identified as: emptiness, vulnerability and exhaustion as important features. By linking the sub-themes together a common core emerges and is labeled existential vacuum identical to main theme (). The results are illustrated as overlapping experiences ().

Discussion

Based on the authors’ previous studiesCitation1,Citation3–Citation5 and the findings from the thematic analysis in this study, we now want to extend the discussion in order to deepen our understanding of grief processes. Furthermore, we will highlight important elements when developing integrated programs in chronic pain- and grief management.

In both of our studiesCitation3–Citation5 the participants experienced loss and grief and realized that some sort of help was needed. To offer help a phenomenological perspective on loss and grief caused by death and chronic pain, means that the whole life situation must be considered in program development. Grief is a normal human response to a significant loss. The death of a close relative is considered the ultimate loss. Such loss is obvious and the grief process is recognized by attention from others. However, with chronic pain the loss may be complete or partial. The grief which follows may be less obvious and may limit support from other people.Citation2 The present results indicate a relationship between loss, grief and chronic nonmalignant pain. This is supported by both previous and more recent research which document a relationship between these phenomena and the development of illness.Citation8,Citation27 ParkesCitation8 has identified parallel processes of grieving independent of the type of loss.

Results from several studies on writing and the health effects indicate that positive health is achievable through writing about traumatic and demanding experiences.Citation28,Citation29 Furthermore, interventions based on a CBT approach offered to patients suffering from chronic pain, with active patient participation, indicate positive results.Citation30 Writing therapy has emerged as a way to ease grief related to loss by deathCitation5 and chronic pain by tapping into the healing power of the unconscious.Citation31 Whitley-ReedCitation10 reports that grief therapy may be effective in reducing pain in a group of chronic pain sufferers. Grief supporting in groups are common and helpful because the patients represent common life experience and this gives opportunity to tell one’s own story and ventilate feelings.Citation3–Citation5,Citation32 These benefits from group approaches are also described by YalomCitation12 who emphasizes the importance of interpersonal learning, self-disclosure and the expression of emotions. Taking together, these results support the importance of developing chronic pain- and grief management programs.

In accordance with our view, professional intervention must be aimed directly at each individual relation and the position in “the relearning and adaptation process.”Citation1 As such, grief cannot be reduced to observable and fragmented symptoms.Citation1,Citation5 Surprisingly, most of the identified experiences caused by loss and grief related to death of a close person and suffering from chronic pain were overlapping (categories in ). These overlapping experiences are incorporated in the sub-themes emptiness, vulnerability and exhaustion. Based on this understanding, a clarifying model is suggested, which indicates that these life phenomena not only overlap, but also have an inner dynamic and a common core (). These experiences also involve several cognitive, affective and bodily manifestations which might be met by using a cognitive behavioral approach. Despite some identified different experiences which are naturally connected to the specific losses, we argue that the common experiences are central when developing an integrated program in chronic pain- and grief management. In addition, the elements in the common core become basic areas to address in future clinical programs.

However, the first and foremost plan must involve the dialectic process between “relearning and adaptation” as described in our previous theoretical work.Citation1 Here a model illustrates parallel processes characterized by conflicting experiences such as despair and hope, lack of understanding and insight, meaning disruption and increased meaning, bodily discomfort and reintegrated body.Citation1 The present extended theoretical fundament including the complexity described above represent a challenge in clinical practice. Such knowledge presupposes that health care workers have adequate knowledge about each of the life experiences, as well as the common core and how they appear in each individual. If not, the burden for those experiencing losses and grief may increase and become even heavier.

Usually, as time passes by, the sufferer and her or his network will obtain an optimal functional level. However, some patients are unable to handle their losses effectively, and this may intensify the painful experience.Citation6 The challenge is to find out who will need some sort of support from health care providers. In order to better understand the poorly adaptive as well as the adaptive processes, one must examine the unique movements. Throughout the grief process thoughts and feelings may vary in their nature and intensity. The core represents experiences which may be multifaceted and so overwhelming that the patient becomes unable to take action. Listening to the patients’ expressions of grief can be therapeutic in itself.Citation33 The unique experience becomes basic for intervention. Summing up, the rehabilitation process must pay attention to the unique experiences illustrated in the “relearning the world – adaptation model”Citation1 and extended by the present “Common core model” (), linking part oneCitation1 and part two of these two-part articles together.

Implications for practice

Grief work is recognized to be an important (although painful) process which also may create relief. It is essential to be aware that the grieving process varies in strength and endurance,Citation5 so that the programs must consider individual variations in length and intensity in the follow-up. When preparing interventions, attention must also be paid to “the relearning and adaptation process”,Citation1 the interplay between chronic pain, loss and grief and the common core. This represents an integrated framework developed by linking part one and part two of these two-part articles together. An important aim in grief and pain management programs, is to create hope, insight, meaning, and a reintegrated body.Citation1 We suggest that writing theory, from the grief management program may be integrated in the pain management program, based on a CBT approach and vice versa. Such combination might represent an improved intervention for people dealing with grief related to loss and nonmalignant chronic pain.

Based on this comparative study, a summary of points for developing and implementing such programs is suggested: an introduction of systematic writing and homework combined with a supervised dialogue, where thoughts and feelings related to what is lost is conceptualized and processed. In addition, practical elements such as focusing on supportive factors, interpersonal learning, self-revelation and self-understanding must be highlighted.Citation12 Establishing a good relation between the health care provider, the sufferer and social support is described as the single most underlying important skill if interventions are to succeed.Citation32 These suggestions might lead to more focus on the relation between chronic pain, loss and grief and better treatment.

Conclusion

Experiencing grief caused by death of someone close and chronic nonmalignant pain, is about whole bodies and the unique experiences. An extended approach has been developed for grief interventions based on the authors’ previous work, the first two-part article and our present theoretical framework. We believe there is value in future research to consider loss and grief caused by death of someone close or by chronic pain more broadly, to develop our knowledge base. As such, understanding the processes involved in one of the loss and grief situations may help us understand the processes involved in the other. It may also turn out that treatment issues are similar in the different kinds of losses which are experienced. This study has led to new questions that might be further investigated in a pilot project for clinical practice using our outlined models and suggestions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FurnesBDysvikEDealing with grief related to loss by death and chronic pain. An integrated theoretical framework. Part 1Patient Preference and Adherence2010413514020622913

- LindgrenCLChronic sorrow in long-term illness across the life spanMiller JFitzgeraldCoping with Chronic Illness, Overcoming PowerlessnessPhiladelphia, PADavis2000125143

- DysvikEHealth-related Quality of Life and Coping in Rehabilitation of People Suffering from Chronic Pain Doctoral thesis. University of Bergen, Norway, 2006

- DysvikEKvaløyJTStokkelandRNatvigGKThe effectiveness of a multidisciplinary pain management programme managing chronic pain on pain perceptions, health-related quality of life and stages of change– A non-randomized controlled studyInt J Nurs Stud20104782683520036362

- FurnesBÅ Skrive Sorgen – Bearbeidelse av sorg. Prosessorientert skriving i møte med en fenomenologisk språkforståelse. En hermeneutisk fenomenologisk studie av skriving som sorgbearbeidelse hos etterlatte Doctoral thesis. University of Bergen, Norway, 2008

- GatchelRJAdamsLPolatinPBKishinoNDSecondary loss and pain – Associated disability: Theoretical overview and treatment implicationsJ Occ Rehab20021299109

- MillerEDOmarzuJNew directions in loss researchHarveyJHPerspectives on loss, a sourcebookPhiladelphiaTaylor and Francis1998320

- ParkesCMBereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult LifeLondonPenguin1986

- WalkerJSofaerBHollowayIThe experience of chronic back pain: Accounts of loss in those seeing help from pain clinicsEur J Pain20061019920716490728

- Whitley-ReedLThe efficacy of grief therapy as a treatment modality for individuals diagnosed with co-morbid disorders of chronic pain and depressionDissertation Abstracts International: Section B- Sciences and Engineering1999597B3710

- KeefeFJBeauprePMGilKMRumbleMEAspnesAKGroup therapy for patients with chronic painTurkDCGatchelRJPsychological Approaches to Pain Management A practitioner’s handbook2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press2002234255

- YalomIDThe Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy5th edNew York, NYBasic Books2005

- LintonSJUnderstanding Pain for Better Clinical Practice: A psychological perspectiveLondon, UKElsevier2005

- TurkDCMonarchESBiopsychosocial perspective on chronic painTurkDCGatchelRJPsychological Approaches to Pain Management A practitioner’s handbook2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press2002329

- TurkDCA cognitive-behavioral perspective on treatment of chronic pain patientsTurkDCGatchelRJPsychological Approaches to Pain Management A practitioner’s handbook2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press2002138158

- VygotskyLTænkning og Sprog IIKøbenhavnH:Reizel1982

- ElbowPWriting without TeachersNew York, NYOxford University Press1973

- MurrayDIndre revisjon – en oppdagelsesprosessBjørkvoldEPenneSSkriveteoriOslo, NorwayLNU/J.W Cappelens Forlag A/S1991

- DystheOHertzbergFHoelTLSkrive for å lære. Skriving i høyere utdanning Abstrakt forlag: Portalserien; 2000

- ElbowPWriting with Power Techniques for mastering the writing processOxford, UKOxford University Press1981

- BrittonJBurgessTMartinNMcLeodARosenHThe development of Writing- abilitiesLondon, UKMacmillan Education19751118

- StenslandPApproaching the Locked Dialogues of the Body- Communicating symptoms through illness diaries Doctoral thesis. Division for General Practice, Department of Public Health and Primary Health Care. University of Bergen, Norway, 2003

- PennebakerJWTelling stories: The health benefits of narrativeLit Med20001931110824309

- SmythJTrueNSoutoJEffects of writing about traumatic experiences: The necessity for narrative structuringJ Soc Clin Psych200120161172

- BrattbergGVäckarklockor för Människor I Livets VäntrumStockholm, SwedenVärkstaden1998

- MelzackRWallPDPain mechanisms: a new theoryScience19651509719795320816

- StroebeMSHanssonROStroebeWSchutHIntroduction: concepts and issues in contemporary research on bereavementStroebeMSHanssonROStroebeWSchutHAmerican Handbook of Bereavement Research. Consequences, coping, and careWashington DCPsychological Association2002322

- FrancisMEPennebakerJWPutting stress into words: The impact of writing on physiological, absentee and self-reported emotional well-being measuresAm J Health Prom19926280207

- SmythJWritten emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variablesJ Consulting Clin Psych199866174184

- TurkDCBurwinkleTACognitive-behavioral perspective on chronic pain patientsCrit Rev Physil Rehab Med2006181138

- RashbaumIGSarnoJEPsychosomatic concepts in chronic painArch Phys Med Rehab2003847685

- Miller KahnACoping with fear and grievingLubkinIMChronic Illness, Impact and InterventionsLondon, UKJones and Bartlett1995241260

- DyregrovKThe Loss of a Child by Suicide, SIDS, and accidents: Consequences, needs and provisions of help Doctoral thesis. University of Bergen, Norway, 2003

Appendix A

Appendix A Content of the pain and grief management program