Abstract

Invasive fungal infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients, such as subjects with hematological malignancies and patients who underwent to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or solid organ transplantation (SOT). Fusarium spp. cause a broad spectrum of infections in humans. Immunologically competent hosts show mainly localized skin infections, whereas disseminated fusariosis occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised patients. Fusarium spp. are resistant to many antifungal agents with equivocal in vitro and in vivo susceptibility to amphotericin B. Voriconazole (VRC) is a triazole shown to be safe, well tolerated, and in vitro efficacious against Fusarium spp. Although clinical experience is limited, many case reports have shown the efficacy of VRC in the treatment of fusariosis.

Introduction

Invasive fungal infections are a major cause of mortality from infection in immunocompromised patients with hematological malignancies, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and solid organ transplantation (SOT) (De Pauw et al 1999; CitationNucci 2003; CitationNucci et al 2003). The introduction of fluconazole prophylaxis in such patients has led to a shift in the epidemiology of fungal infections with a dramatic reduction of the incidence of candidiasis (CitationAnaissie et al 1986; CitationBoutati and Anaissie 1997; CitationMarr et al 2002). By contrast, the incidence of mould infections such as aspergillosis and other non-aspergillar fungal infections has increased significantly (CitationMarr et al 2002; CitationWalsh et al 2004). Among immunocompromised patients, invasive fusariosis is the second most common cause of mould infections after aspergillosis with an increasing incidence (CitationBoutati and Anaissie 1997; CitationNucci 2003; CitationNucci et al 2004).

Fusarium spp. are plant pathogens and soil saprophytes that cause a broad spectrum of infections in humans, including superficial (keratitis, onychomycosis), locally invasive, and disseminated infection. Disseminated fusariosis occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised individuals (CitationNucci et al 2002; Dignani et al 2004). Recently, Nucci et al reported the clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of 61 patients with fusariosis after HSCT (54 allogeneic HSCT, 7 autologous HSCT). The reported incidence of fusariosis ranged from 5 infections per 1000 HSCTs in human leucocyte antigen (HLA) matched related transplantations to 20 infections per 1000 HSCTs in HLA mismatched transplantations. The survival rate was 13%, with a median onset of 13 days from the diagnosis, and the single prognostic factor for death by multivariate analysis was persistent neutropenia (CitationNucci et al 2004). The incidence of invasive fungal infections is also increasing in SOT ranging between 5% and 20% (CitationLodato et al 2006), probably due to the use of more intense immunosuppression regimens to reduce acute allograft rejection. Between 1996 and 2007, 10 cases of fusariosis in patients who underwent SOT were reported in literature. Nine of them were localized whereas one patient experienced disseminated fusariosis. The infection resolved in 9 of these patients. None died from fusariosis (CitationYoung and Meyers 1979; Heinz et al 1996; Arney et al 1997; Girardi et al 1999; CitationLinden et al 2000; CitationSampathkumar et al 2001; CitationCocuroccia et al 2003; Garbino et al 2004; Lodato et al 2005). Part of these data are presented in .

Table 1 Cases of fusariosis found by a computerized search of MEDLINE and published from January 2000 to April 2007

The incidence of fusariosis and its mortality rate are significantly higher in patients with hematological malignancies and in those with allogeneic HSCT due to more intense immunosuppression and profound and prolonged neutropenia. The genus Fusarium comprises a large number of species (more than 20) and the most common human pathogen is Fusarium solani isolated in approximately half of the reported infections. The remaining cases of human fusariosis are caused by Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium moniliforme, and Fusarium verticillioides, each of which account for 10%–14% of all infections. Considering the increasing incidence of Fusarium spp. infections, an increased virulence of these species cannot be excluded (CitationNelson et al 1994; CitationNucci et al 2003).

Fusarium spp. manifest an inherent resistance to a multitude of antifungal agents, making the treatment of fusariosis a challenging task especially in severely immunosupressed individuals with hematological malignancies or transplant recipients. In this patient population fusariosis is frequently fatal (Al-Abdely 2003). Despite its equivocal in vitro susceptibility and treatment failures (CitationArikan et al 1999), amphotericin B has remained the drug of choice for the management of disseminated fusariosis (CitationGuarro et al 1995). Voriconazole (VRC) is a triazole antifungal agent approved by the FDA in May 2002 for the treatment of fungal infections including aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, scedosporiosis, and fusariosis since in vitro data and clinical evidence indicated activity against Fusarium spp. (CitationArikan et al 1999; Espinel-Ingroff et al 2001; CitationPaphitou et al 2002; CitationConsigny et al 2003; CitationHerbrecht 2004).

Treatment of fusariosis

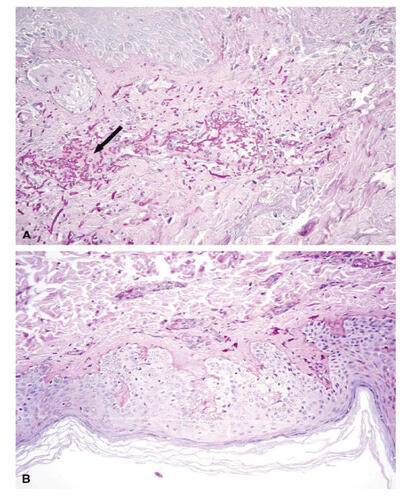

Fusarium spp. can cause local and, most importantly, disseminated infections in immunocompromised patients with involvement of multiple organs including the skin ().

Figure 1 Patient with disseminated fusariosis and skin involvement. The lesions are seen most commonly on extremities and appear as widespread, violaceous (A) or erythematous indurated elements (B). With the resolution of the infection the skin lesions become darker (C) and the lesions disappear (D).

For the clinician taking care of patients with hematological malignancies disseminated fungal infections constitute one of the most difficult challenges. In this patient population Fusarium spp. is an emerging cause of non-Aspergillus mould infection and is associated with high mortality. In 1997 Boutati and Anaissie (CitationBoutati and Anaissie 1997) described 43 patients with hematological malignancies who developed invasive Fusarium spp. infection. Thirteen of these (30%) responded to therapy with amphotericin B deoxycholate (AMBD) or its lipid formulations [liposomal amphotericin B (AmB-L); amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC)]. The majority (70%) of patients died from the infection while a resolution was only seen in patients who ultimately recovered from cytopenia (CitationBoutati and Anaissie 1997; CitationKontoyiannis et al 2004). More recently, 84 cases of Fusarium spp. infection in patients with hematological malignancies were reported (CitationNucci 2003). Of them, only 21% were alive 90 days after the diagnosis.

Polyenes

Current therapy for refractory invasive fungal infections caused by less-common moulds remains inadequate. Since fusariosis may mimic aspergillosis in its clinical manifestations, affected patients were usually treated with amphotericin B, an agent with poor activity in vitro against Fusarium spp. (CitationPfaller et al 2002), whereas evidence of a good in vivo activity is reported with ABLC (CitationLodato et al 2006) and AmB-L (CitationJensen et al 2004; CitationSelleslag 2006).

Azoles

Itraconazole

Itraconazole was demonstrated to exert negligible activity against Fusarium spp. (CitationPfaller et al 2000). It has rarely been administered against Fusarium spp. infections with unequivocal results. Additionally it has been demonstrated that amphotericin B and VRC are consistantly more effective than itraconazole against Fusarium isolates (CitationLewis et al 2005). Itraconazole has seldom been administered for Fusarium infections with nonunivocal results (CitationReis et al 2000; CitationPereiro et al 2001; CitationCocuroccia et al 2003; CitationVincent et al 2003).

Voriconazole

VRC is an extended-spectrum, synthetic triazole derivative of fluconazole, whose mechanism of action is inhibition of the cytochrome P450 (CYP)-dependent enzyme 14-α-sterol demethylase, preventing the fungal cell membrane synthesis and causing its disruption (CitationDenning et al 2002; CitationGhannoum and Kuhn 2002; CitationJohnson and Kauffman 2003; CitationHerbrect 2004; CitationScott and Simpson 2007).

Intravenous and/or oral VRC is generally well tolerated. Nevertheless, approximately half of all subjects receiving VRC experienced at least one treatment-related adverse event (CitationGhannoum and Kuhn 2002; CitationAlkan et al 2004; CitationHerbrect 2004; EMEA summary of product characteristics 2007; CitationScott and Simpson 2007).

In Candida spp. VRC is fungistatic, whereas in filamentous organisms it is fungicidal. VRC shows in vitro activity against a variety of yeasts, filamentous fungi and dimorphic moulds. Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., and Scedosporium spp. are the pathogens against which VRC has been approved for treatment, whereas it has little or no activity against Zygomycetes.

Susceptibility of filamentous fungi to VRC was tested by 3 studies (CitationJohnson et al 1998; Espinel-Ingroff et al 2001; CitationLinres et al 2005). While Johnson and Espinel-Ingroff obtained minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of between 2 and 8 μg/mL, more recently Linares et al showed that Fusarium spp. display greater susceptibility to VRC (MICs 0.25–4 μg/mL) than that reported before (CitationLinares et al 2005). Although animal data suggest a possible correlation between the efficacy of VRC and MIC values, there was no correlation between clinical outcome and MIC values in clinical trials (EMEA 2007).

The efficacy and safety of VRC for the primary treatment of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients has been described in randomized, non-blind, multinational trials and in observational studies (CitationDenning et al 2002; CitationGhannoum and Kuhn 2002; CitationHerbrecht et al 2002; CitationHerbrecht 2004; CitationAlvarez-Lerma et al 2005; CitationMouas et al 2005; CitationScott and Simpson 2007), but also many case reports have shown the efficacy of VRC in the treatment of fusariosis () (CitationReis et al 2000; CitationConsigny et al 2003; CitationPerfect et al 2003; CitationRodriguez et al 2003; CitationVincent et al 2003; CitationBigley et al 2004; Garbino et al 2004; CitationGuimerá-MartÍn-Neda et al 2004; CitationGuzman-Cotrilli et al 2004; CitationPolizzi et al 2004; CitationDurand et al 2005; CitationGorman et al 2006; CitationHsu et al 2006; CitationSagnelli et al 2006; CitationStanzani et al 2006; CitationBunya et al 2007). Thirty-four English language case reports were found by a computerized search of MEDLINE from January 2000 to April 2007. We found 20 disseminated fusariosis and 14 localized infections: 10 ocular involvements, 2 cutaneous lesions, 1 pneumonia, 1 peritonitis. Hematological disease was the underlying setting in 18 patients, while solid tumor and chronic emphysema affected one patient each. All the patients with disseminated infection were immunodepressed because of chemotherapy, or HSCT, or steroids administration, as shown in . The overall response to VRC for disseminated fusariosis was 63% (12/19 evaluable). Treatment with VRC was initiated in 19 patients with the iv loading dose of 6 mg/kg bid, followed by the maintenance dose of 4 mg/kg bid. The switch to the oral treatment (200 mg bid) was made in 18 patients. Only one patient received the oral formulation of VRC from the start. For localized infections, VRC was administered iv to 5 patients, eventually followed by oral administration for long-term maintenance. Topical VRC preparation could be added. In 6 patients oral voriconazole was administered from the beginning, while 2 patients received only topical formulations. In 3 patients with disseminated fusariosis, combined therapy consisting in voriconazole and AmB-L was administered, while VRC was given as salvage treatment in 4 patients with disseminated fusariosis (data shown in ).

Recently, Perfect et al reported a multicenter, open-label, clinical study to assess the efficacy and safety of VRC for the treatment of less-common, emerging or refractory invasive fungal infections (CitationPerfect et al 2003). Three-hundred and one immunocompromised patients were studied. The drug was administered iv at recommended dosages for at least 3 days, and the median duration of iv treatment was 18 days (range 1–138 days). Thereafter patients could be switched to oral treatment. The median duration of oral administration was 69 days (range 1–326 days). In the study they treated 11 fusariosis, showing 45% of satisfactory global response with respect to the high mortality rate (70%) for disseminated fusariosis treated with other therapies (CitationKrcmery et al 1997; CitationBoutati and Anaissie 1997; CitationPerfect et al 2003). These results were consistent with data from previous reports focused on the use of VRC in critically ill patients. They confirm its good profile concerning safety and tolerability, with an incidence of treatment-related toxicities, such as visual disturbances and rashes, requiring suspension for 3.5% of patients, but none of the toxicities were severe. Also liver function abnormalities were noted in >10% of patients, but only 2.4% had their treatment discontinued, confirming previously reported data (CitationPotoski and Brown 2002).

Posaconazole

Posaconazole (PSC) is a potent extended spectrum tiazole that has been shown to be highly active against yeasts and moulds, including Fusarium spp. (Espinel-Ingrof et al 2004; CitationTorres et al 2005). Recently, Raad et al described a clinical experience with PSC utilized for refractory fusariosis or for patients intolerant to conventional antifungal therapy in 21 cases, with an overall response of 48%. This result is comparable with those seen with VRC, and prolonged neutropenia was an unfavorable risk factor of non-response (20% in patients who recovered from myelosuppression versus 67% in patients who did not recover) (CitationRaad et al 2006). Moreover, 4 cases of ocular infection and 1 case of pneumonia by Fusarium spp. were described, treated and resolved with PSC after failure of treatment with VRC (iv, oral, and topical formulation) and other antifungal drugs (CitationSponsel et al 2002; CitationHerbrecht et al 2004; CitationTue et al 2007).

PSC is administered as an oral suspension with food and this could limit its use in critically ill patients.

These results suggest PSC can be considered an appropriate alternative antifungal therapy to amphotericin B formulation, leading to results similar to those once found with VRC.

Echinocandins

Fusarium spp. are usually resistant to echinocandins by standard susceptibility testing (CitationSpellberg et al 2006). Instead, a case of fungemia sustained by Fusarium spp. resistant to amphotericin B was resolved with caspofungin at standard doses in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia (CitationApostolidis et al 2003). A recent murine model disclosed that caspofungin at 1 mg/kg/day improved survival during active fusariosis, despite lack of reduction in fungal burden (CitationSpellberg et al 2006), suggesting a potential role in the treatment of human fusariosis.

Future perspectives

The in vitro interaction of itraconazole, amphotericin B and VRC with anidulafungin against Aspergillus spp. and Fusarium spp. was recently evaluated (CitationPhilip et al 2005). Anidulafungin belongs to the echinocandins antifungal drugs class. The data showed that all drug combinations suggested indifference against Fusarium spp, but not antagonism or synergism. A previous study reported a potential synergistic to additive effect of caspofungin in combination with amphotericin B against Fusarium spp. (CitationDismukes et al 2000). Also the combination of VRC and micafungin was tested showing a synergistic effect against Fusarium spp. (CitationHeyn et al 2005), but clinical studies are needed to confirm these data.

Nystatin is classified among the most efficient antifungal agents, widely used since 1950s, but insoluble in water. The in vitro activity of polymeric complexes of nystatin was investigated against growth inhibition and spore germination of Fusarium oxysporum. These complexes of nystatin were 3–25 times more active than nystatin against spore germination and were effective inhibitors of mycelial growth (CitationCharvalos et al 2002). Their use in the clinical setting has not yet been investigated.

Conclusions

Invasive fusariosis is an emerging cause of mould infections in immunocompromised patients, with usually poor prognosis being Fusarium spp. resistant to most available antifungal agents (CitationNucci 2003). In vitro susceptibility testing may be the only clue in the choice of the appropriate antifungal agent (CitationAl-Abdely 2004). The only antifungal drugs effective against Fusarium spp, as evidenced by their relatively low MICs, are amphotericin B, nystatin, ketoconazole, VRC, and PSC (CitationEspinel-Ingroff 1998; CitationLewis et al 2005; CitationTeixeira et al 2005; CitationCuenca-Estrella et al 2006), whereas fluconazole, itraconazole, and the echinocandins are not active alone against Fusarium spp. (CitationEspinel-Ingroff 1998; CitationMarco et al 1998; CitationPfaller et al 1998; CitationLewis et al 2005). VRC has a slightly broader spectrum of activity against most moulds, showing very good in vitro activity against Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp, Scedosporium spp. (CitationDenning et al 2003; CitationLewis et al 2005; CitationLinares et al 2005). Many case reports have demonstrated the efficacy of VRC in the treatment of fusariosis (CitationReis et al 2000; CitationConsigny et al 2003; CitationPerfect et al 2003; CitationRodriguez et al 2003; CitationVincent et al 2003; CitationBigley et al 2004; Garbino et al 2004; Guimerá-MartÍn-Neda et al 2004; Guzman-Cotrilli et al 2004; CitationPolizzi et al 2004; CitationDurand et al 2005; CitationGorman et al 2006; CitationHsu et al 2006; CitationSagnelli et al 2006; CitationStanzani et al 2006; CitationBunya et al 2007), with a 63% overall response for disseminated fusariosis, while Perfect et al reported a 45% satisfactory global response, with respect to the high mortality rate (70%) for patients treated with other antifungal drugs (CitationPerfect et al 2003).

PSC is a new potent extended spectrum tiazole that has been shown to be active against Fusarium spp. (Espinel-Ingrof et al 2004; CitationTorres et al 2005; CitationRaad et al 2006). However, no clinical trials have hitherto compared PSC with VRC or addressed the relative use of these two broad spectrum tiazole agents in the management of fusariosis. Polymeric complexes of nystatin have been investigated against Fusarium oxysporum, but there have been no published clinical trials.

In conclusion, treatment of emerging invasive fungal infections is a major challenge, with no standardized therapy and high mortality rates. VRC seems to be the most promising antifungal agent for the treatment of disseminated fusariosis in immunocompromised subjects, but more clinical evidence is required.

References

- Al-AbdelyHMManagement of rare fungal infectionsCurr Opin Infect Dis2004175273215640706

- AlkanYHaefeliWEBurhenneJVoriconazole-induced QT interval prolongation and ventricular tachycardia: a non-concentration-dependent adverse effectClin Infect Dis200439e495215472801

- Alvarez-LermaFNicolas-ArfelisJMRodriguez-BorreganJCClinical use and tolerability of voriconazole in the treatment of fungal infections in critically ill patientsJ Chemother2005174172716167522

- AnaissieEKantarjianHJonesPFusarium. A newly recognized fungal pathogen in immunosuppressed patientsCancer198657214153457624

- AnandiVVishwanathanPSasikalaSFusarium solani breast abscessIndian J Med Microbiology2005231989

- ApostolidisJBouzaniMPlatsoukaEResolution of fungemia due to Fusarium spp. in a patient with acute leukemia treated with caspofunginClin Infect Dis20033613495012746788

- ArikanSLozano-ChiuMPaetznickVMicrodilution susceptibility testing of amphotericin B, itraconazole, and voriconazole against clinical isolates of Aspergillus and Fusarium speciesJ Clin Microbiol19993739465110565912

- AustenBMcCarthyHWilkinsBFatal disseminated Fusarium infection in acute lymphoblastic leukemia in complete remissionJ Clin Pathol2001544889011376027

- BigleyVHDuarteRFGoslingRDFusarium dimerum infection in a stem cell transplant recipient treated successfully with voriconazoleBone Marrow Transplant2004348151715361915

- BodeyGPBoktourMMaysSSkin lesions associated with Fusarium infectionJ Am Acad Dermatol2002476596612399756

- BoutatiEAnaissieEJFusarium, a significant emerging pathogen in patients with hematologic malignancy: ten years’ experience at a cancer center and implications for managementBlood19979099910089242529

- BunyaVYHammersmithKMRapuanoCJTopical and oral voriconazole in the treatment of fungal keratitisAm J Ophthalmol2007143151317188052

- CharvalosETsatsakisATzatzarakisMNew nystatin polymeric complexes and their in vitro antifungal evaluation in a model study with Fusarium oxysporumMycopathologia2002153151911913760

- CocurocciaBGaidoJGubinelliELocalized cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis caused by Fusarium spp. infection in a renal transplant patientJ Clin Microbiology2003419057

- ConsignySDhedinNDatryASuccessful voriconazole treatment of disseminated Fusarium infection in an immunocompromised patientClin Infect Dis2003373111312856225

- CudilloLGirmeniaCSantilliSBrekthrough fusariosis in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia receiving voriconazole prophylaxisClin Infect Dis20054012121315791530

- Cuenca-EstrellaMGomez-LopezAMelladoEHead-to-head comparison of the activities of currently available antifungal agents against 3,378 Spanish clinical isolates of yeasts and filamentous fungiAntimicrob Agents Chemother2006509172116495251

- DenningDWRibaudPMilpiedNEfficacy and safety of voriconazole in the treatment of acute invasive aspergillosisClin Infect Dis2002345637111807679

- DenningDWKibblerCCBarnesRABritish Society for Medical Mycology proposed standards of care for patients with invasive fungal infectionsLancet Infect Dis200332304012679266

- DismukesWEIntroduction to antifungal drugsClin Infect Dis200030653710770726

- DurandMLKimIKD’AmicoDJSuccessful treatment of Fusarium endophtalmitis with voriconazole and Aspergillus endophtalmitis with voriconazole plus caspofunginAm J Ophtalmology20051405524

- Espinel-IngroffAComparison of In vitro activities of the new triazole SCH56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeastsJ Clin Microbiol199836295069738049

- Espinel-IngroffAFothergillAGhannoumMQuality control and reference guidelines for CLSI broth microdilution susceptibility method (M38-A Document) for amphotericin B, itraconazole, posaconazole and voriconazoleJ Clini Microbiol20054352436

- European Agency for the Evaluation of Medical ProductsVFEND: summary of product characteristics [online]2007 URL: http://www.emea.eu.int.

- GarbinoJUckayIRohnerPFusarium peritonitis concomitant to kidney transplantation successfully managed with voriconazole: case report and review of the literatureTranspl Int2005186131815819812

- GhannoumMAKuhnDMVoriconazole – better chances for patients with invasive mycosesEur J Med Res200272425612069915

- GiaconiJAMarangonFBMillerDVoriconazole and fungal keratitis: a report of two treatment failuresJ Ocul Pharmacol Ther200622437917238810

- GormanSRMagiorakosAPZimmermanSKFusarium oxysporum pneumonia in an immunocompetent hostSouth Med J2006996131616800418

- GuarroJGeneJOpportunistic fusarial infections in humansEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis199514741548536721

- Guimerá-Martí-NedaFGarcía-BustínduyMNoda-CabreraACutaneous infection by Fusarium: successful treatment with oral voriconazoleBritish J Dermatol200415077095

- Guzman-CottrillJAXiaotianZhengChadwickEGFusarium solani endocarditis successfully treated with liposomial amphotericin B and voriconazolePediatric Infect Dis J200423105960

- HamakiTKamiMKishiAVesicles as initial skin manifestation of disseminated fusariosis after non-myeloablative stem cell transplantationLeuk Lymphoma200445631315160931

- HerbrechtRDenningDWPattersonTFVoriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosisN Engl J Med20023474081512167683

- HerbrechtRVoriconazole: therapeutic review of a new azole antifungalExpert Rev Anti Infect Ther200424859715482215

- HerbrechtRKesslerRKravanjaCSuccessful treatment of Fusarium proliferatum pneumonia with posaconazole in a lung transplant recipientJ Heart Lung Transplant2004231451415607679

- HeynKTredupASalvenmoserSEffect of voriconazole combined with micafungin against Candida, Aspergillus, and Scedosporium spp and Fusarium solaniJ Antimicrob Chemother20054951579

- HsuCKHsuMMLeeJYFusariosis occurring in an ulcerated cutaneous CD8+ T cell lymphoma tumorEur J Dermatol20061629730116709499

- JensenTGGahrn-HansenBArendrupMFusarium fungemia in immunocompromised patientsClin Microbiol Infect20041049950115191376

- JohnsonEMSzekelyAWarnockDWIn-vitro activity of voriconazole, itraconazole and amphotericin B against filamentous fungiJ Antimicrob Chemother199842741510052897

- JohnsonLBKauffmanCAVoriconazole: a new triazole antifungal agentClin Infect Dis200336630712594645

- KhouryHBallNJDisseminated fusariosis in a patient with acute leukemiaBr J Haematol2003120112492568

- KivivouriSMHoviLVetternantaKInvasive fusariosis in two transplanted childrenEur J Pediatr2004163692315322867

- KontoyiannisDPBodeyGPHannaHOutcome determinants of fusariosis in a tertiary care cancer center: the impact of neutrophil recoveryLeuk Lymphoma2004451394115061210

- KrcmeryVJrJesenskaZSpanikSFungaemia due to Fusarium spp. in cancer patientsJ Hosp Infect19973622389253703

- LewisRWiederholdNPKlepserMEIn vitro pharmacodynamics of amphotericin B, itraconazole, and voriconazole against Aspergillusm, Fusarium and Scedosporium sppAntimicrob Agents Chemother2005499455115728887

- LinHCChuPHKuoYHClinical experience in managing Fusarium solani keratitisInt Clin Pract20055954954

- LinaresMJCharrielGSolÍFSusceptibility of filamentous fungi to voriconazole tested by two microdilution methodsJ ClinMicrobiol2005432503

- LindenPWilliamsPChanKMEfficacy and safety of amphotericine B lipid complex injection (ABLC) in solid organ transplant recipients with invasive fungal infectionClin Transpl20001432939

- LodatoFTaméMRMontagnaniMSystemic fungemia and hepatic localization of Fusarium solani in a liver transplanted patient: an emerging fungal agentLiver Transpl20061217111417058254

- MadariagaMGKohlSDisseminated fusariosis presenting with pulmonary nodules following a line infectionBraz J Infect Diseases200610426

- MarcoFPfallerMAMesserSAAntifungal activity of a new triazole, voriconazole (UK-109, 496), compared with three other antifungal agents tested against clinical isolates of filamentous fungiMed Mycol199836433610206756

- MarrKACarterRACrippaFEpidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipientsClin Infect Dis2002349091711880955

- MouasHLutsarIDupontBVoriconazole for invasive bone aspergillosis: a worldwide experience of 20 casesClin Infect Dis20054011414715791514

- MusaMOAl EisaAHalimMThe spectrum of Fusarium infection in immunocompromised patients with hematological malignancies and in non-immunocompromised patients: a single institution experience over 10 yearsBr J Haematol2000108544810759712

- NelsonPEDignaniMCAnaissieEJTaxonomy, biology, and clinical aspects of Fusarium speciesClin Microbiol Rev199474795047834602

- NucciMAnaissieEJCutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised host: implication for diagnosis and managementClin Infect Dis2002359092012355377

- NucciMEmerging moulds: Fusarium, Scedosporium and Zygomycetes in transplant recipientsCurr Opin Infect Dis2003166071214624113

- NucciMAnaissieEJQueiroz-TellesFOutcome predictors of 84 patients with hematologic malignancies and Fusarium infectionCancer2003983151912872351

- NucciMMarrKAQueiroz-TellesFFusarium infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipientsClin Infect Dis20043812374215127334

- OliveiraJSKerbauyFRColomboALFungal infections in marrow transplant recipients under antifungal prophylaxis with fluconazoleBraz J Med Biol Res2002357899812131918

- PaphitouNIOstrosky-ZeichnerLPaetznickVLIn vitro activities of investigational triazoles against Fusarium species: effects of inoculum size and incubation time on broth microdilution susceptibility test resultsAntimicrob Agents Chemother200246329830012234865

- PereiroMJrAbaldeMTZulaicaAChronic infection due to Fusarium oxysporum mimicking lupus vulgaris: case report and review of cutaneous involvement in fusariosisActa Derm Venereol20018151311411917

- PerfectJRMarrKAWalshTJVoriconazole treatment for less-common, emerging, or refractory fungal infectionsClin Infect Dis20033611223112715306

- PfallerMAMarcoFMesserSAIn vitro activity of two echinocandin derivatives, LY303366 and MK-0991 (L-743, 792), against clinical isolates of Aspergillus, Fusarium, Rhizopus, and other filamentous fungiDiagn Microbiol Infect Dis19983025159582584

- PfallerMAMesserSAMillsKIn vitro susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi: comparison of Etest and reference microdilution methods for determining itraconazole MICsJ Clin Microbiol20003833596110970383

- PfallerMAMesserSAHollisRJAntifungal activities of posaconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole compared to those of itraconazole and amphotericin B against 239 clinical isolates of Aspergillus spp. and other filamentous fungi: report from SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 2000Antimicrob Agents Chemother2002461032711897586

- PhilipAOdabasiZRodriguezJIn vitro synergy testing of anidulafungin with itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against Aspergillus spp and Fusarium sppAntimicrob Agents Chemother2005493572416048988

- PolizziASiniscalchiCMastromarinoAEffect of voriconazole on a corneal abscess caused by FusariumActa Ophtalmol Scand2004827624

- PotoskiBABrownJThe safety of voriconazoleClin Infect Dis2002345637111807679

- RaadIHachemRYHerbrechtRPosaconazole as salvage treatment for invasive fusariosis in patients with underlying hematological malignancies and other conditionsClin Infect Dis200642139840316619151

- ReisASundmacherRTintelnotKSuccessful treatment of ocular invasive mould infection (fusariosis) with the new antifungal agent voriconazoleBr J Ophthalmol2000849323310979655

- RodriguezCALuján-ZilbermannJWooderdPSuccessful treatment of disseminated fusariosisBone Marrow Transpl20033141112

- SagnelliCFumagalliLPrigitanoASuccessful voriconazole therapy of disseminated Fusarium verticillioides infection in an immunocompromised patient receiving chemotherapyJ Antimicrob Chemother200657796816469850

- SampathkumarPPayaCVFusarium infection after solid organ transplantClin Infect Dis20013212374011283817

- ScottLJSimpsonDVoriconazole: a review of its use in the management of invasive fungal infectionsDrugs2007672699817284090

- SelleslagDA case of fusariosis in an immunocompromised patient successfully treated with liposomal amphotericin BActa Biomed200677Suppl 232516918066

- SinghNImpact of current transplantation practices on the changing epidemiology of infections in transplant recipientsLancet Infect Dis200331566112614732

- SpellbergBSchwartzJFuYComparison of antifungal treatments for murine fusariosisJ Antimicrob Chemother200658973916973654

- SponselWEGraybillJRNevarezHLOcular and systemic posaconazole (SCH-56592) treatment of invasive Fusarium solani keratitis and endophthalmitisBr J Ophthalmol2002868293012084760

- StanzaniMVianelliNBandiniGSuccessful treatment of disseminated Fusariosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with the combination of voriconazole and liposomial amphotericinB J Infect200653e2436

- TeixeiraABSilvaMLyraLAntifungal susceptibility and pathogenic potential of environmental isolated filamentous fungi compared with colonizing agents in immunocompromised patientsMycopathologia20051601293516170608

- TorresHAHachemRYChemalyRFPosaconazole: a broad-spectrum tiazole antifungalLancet Infect Dis200557758516310149

- TuEYMcCartneyDLBeattyRFSuccessful treatment of resistant ocular fusariosis with posaconazole (SCH-56592)Am J Ophtalmol20071432227

- VincentALCabreroJEGreeneJNSuccessful voriconazole therapy of disseminated Fusarium solani in the brain of a neutropenic cancer patientCancer Control2003104141914581897

- WalshTJGrollAHiemenzJInfections due to emerging and uncommon medically important fungal pathogensClin Microbiol Infect200410Suppl 1486614748802

- YoungCNMeyersAMOpportunistic fungal infection by Fusarium oxysporum in a renal transplant patientSabouraudia19791721923394364