Abstract

Purpose

Heart failure is the ultimate complication of cardiac involvements in diabetes. The purpose of this review was to summarize current literature on heart failure among people with diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

Method

Bibliographic search of published data on heart failure and diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa over the past 26 years.

Results

Heart failure remains largely unexplored in general population and among people with diabetes in Africa. Heart failure accounts for over 30% of hospital admission in specialized cardiovascular units and 3%–7% in general internal medicine. Over 11% of adults with heart failure have diabetes. Risk factors for heart failure among those with diabetes include classical cardiovascular risk factors, without evidence of diabetes distinctiveness for other predictors common in Africa. Prevention, management, and outcomes of heart failure are less well known; recent data suggest improvement in the management of risk factors in clinical settings.

Conclusions

Diabetes mellitus is growing in SSA. Related cardiovascular diseases are emerging as potential health problem. Heart failure as cardiovascular complication remains largely unexplored. Efforts are needed through research to improve our knowledge of heart failure at large in Africa. Multilevel preventive measures, building on evidences from other parts of the world must go along side.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, accounted for in major part by type 2 diabetes is increasing alarmingly in all parts of the world, including sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (CitationWild et al 2004). According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimations, 246 millions people around the world suffer from diabetes in 2007. This figure will increase by 55% to reach 380 million by the year 2025 (CitationIDF 2006). Diabetes-related complications, led by cardiovascular complication (CVD) are already contributing a great deal to the global burden of disease (CitationRoglic et al 2005). In General, up to 80% of deaths among people with diabetes occur thru CVD, and CVD account for 75% of hospital admission in diabetes. Numerous epidemiological studies are concordant over the fact that the risk of experiencing a CVD event in people with diabetes is two to four times greater than that among those without diabetes (CitationKannel and McGee 1979; CitationPanzram 1987; CitationStamler et al 1993; CitationAPCSC 2003). While atherosclerotic vascular disease accounts for much of the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among diabetic patients, congestive heart failure (CHF) is another key complication associated with diabetes, with an incidence that is two to five times greater than that among individuals without diabetes (CitationAPCSC 2003). Once heart failure occurs, patients with diabetes have poorer prognosis than their nondiabetic counterparts.

Despite the growing importance of diabetes mellitus in SSA, evidence to support the related complications and particularly cardiovascular complications are still few. In a recent review, we have shown that although considered to be rare, CVD was on the rise among people with diabetes in SSA and was regularly associated with classical risk factors (CitationKengne et al 2005). However, individual cardiovascular complications and more precisely heart failure among people with diabetes in SSA are less well known. We aim in this review to summarize currently existing literature on heart failure in diabetes in SSA. Such information has relevance both for clinical and epidemiological purposes, given the rapidly changing pattern of disease occurrence in this part of the world.

Source of data

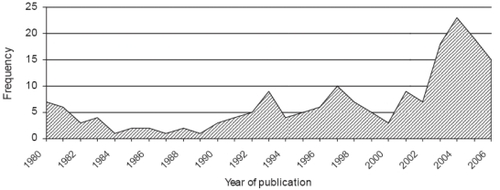

We searched MEDLINE® and reference lists of literature on heart failure and diabetes in SSA in June 2007. Initial MEDLINE search using the keys words “heart failure”, “diabetes”, and “Africa” provided 23 entries spanning from 1966 to 2006. This was considered inconsistent and an extended search using a combination of key words like “heart failure”, “cardiovascular disease”, “stroke”, and “Africa” without restriction to people with diabetes yielded 1,245 entries extending from 1961 to 2007. Data search used in this review was limited to studies published after 1980. This cut-off was chosen because data collected before 1980 may no longer reflect the current situation of heart failure in SSA. The database obtained was contracted by eliminating duplicates, studies from Northern African countries, studies done on migrant Africans, case reports, and studies without heart failure or cardiovascular disease as main focus. The final database consisted of 181 studies from a number of SSA countries, distributed over the 26 years, which is depicted by . Some of these publications included multiple reports from the same studies. Literature from other parts of the world is used where relevant. The majority of articles were retrospective hospital-based studies in major urban cities that addressed aspects of heart failure and cardiovascular disease including incidence, types, risk factors, management, and outcomes. The data sources are mentioned wherever used in the text.

Figure 1 Evolution of published literature on cardiovascular diseases and heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa over the period 1980–2006.

There are very limited published studies describing the burden of heart failure in SSA, most particularly among people with diabetes. Extrapolations from data published elsewhere have serious limitations. As new and better epidemiological data become available in the region, it will be possible to know the actual burden of heart failure in people with diabetes from this region.

Results and discussion

The burden of diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa

The burden of diabetes in Africa has been presented in details elsewhere (CitationMotala 2002; CitationIDF 2006; CitationKengne and Mbanya 2006). The consistent theme is that the magnitude of diabetes mellitus and related health issues has not been reliably estimated for African countries. Extrapolation from existing point prevalence data suggest that 0.5% to 10% of adult population in Africa suffer from type 2 diabetes (CitationMbanya et al 2006). Plotting these figures on a time scale indicates that the prevalence of diabetes has increased by two- to ten-folds in both rural and urban settings in most African countries over the past two to three decades, (CitationMbanya et al 2006). The Diabetes Atlas provides some estimates and projections of diabetes figures for all its regions. In SSA, 10.4 million individuals currently have diabetes, and projections by the IDF suggest that these figures will exceed 18.7 million by 2025 (CitationIDF 2006). Determinants of the growing prevalence of diabetes in Africa are similar to those reported elsewhere. These include rapid urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, obesity, and unhealthy eating diets (CitationMbanya et al 2006). Available prevalence studies are concordant over the fact that diabetes in Africa is 1.5 to 2 times more frequent in urban compared to rural areas. However, unpublished data from Cameroon suggest an attenuation of this rural–urban gradient with time.

Epidemiology of heart failure in Sub-Saharan Africa

Heart failure is a major and growing public health problem on a global perspective. In spite of the scarcity of published literature on heart failure in SSA, the few available evidence suggest that the rate of hospital admission for heart failure is comparable with rates from the rest of the world, but the pathophysiology and etiologies are different (CitationMayosi 2007). Heart failure failure seems to be mainly due to systolic dysfunction and occurs as a major complication of high blood pressure in Africa and the first cause of hospital admission among those with hypertension () in cardiology units (CitationNjoh 1990; CitationMensah et al 1994). In general internal medicine services, heart failure has been described as the 5–6th cause of admission (CitationBardgett et al 2006). In Zimbabwe, while the proportion of hospital admission of patients with noncommunicable diseases has decreased over time, patients with heart failure have continued to contribute about 6% of hospital admission (CitationBardgett et al 2006). More importantly, over the same period, the proportion of death resulting from heart failure has significantly increased.

Table 1 Prevalence of heart failure among patients with hypertension in selected African countries

The underlying process leading to heart failure in most developed countries is dominated by coronary heart disease (CitationMendez and Cowie 2001). In developing countries and most particularly those of SSA, nonischaemic causes of heart failure are dominant, with hypertensive heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, and cardiomyopathy accounting for over 75% of cases in most series (CitationAmoah and Kallen 2000; CitationMendez and Cowie 2001). However, ischemic cardiomyopathies also seem to be growing in this setting (). That cardiac involvements in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, cor pulmonale, and pericarditis contribute to over 20% of cases of heart failure in SSA reflects the continuing impact of HIV and tuberculosis on heart disease on the continent (CitationMagula and Mayosi 2003; CitationMayosi et al 2005). Earlier reports from SSA highlight the major importance of rheumatic valvular diseases among causes of heart failure. However, recently published data favor hypertension as the dominant cause of heart failure in this part of the world (CitationMayosi 2007). Lessons from the changing epidemiology of heart failure in developed countries suggest that the burden of this disease will dramatically increase over the first half of this century.

Table 2 Main causes of heart failure in African adults

Compared to studies from other part of the world, heart failure in Africa tends to occur at a much younger age with most cases recorded around the 5th and 6th decade (). This young age reflect the major contribution of rheumatic valvular disease to heart failure, but could also be accounted for by the early onset and severity of hypertension among Blacks. As reported elsewhere, most African studies have uniformly described a male predominance among those with heart failure in Africa (). Although heart failure management has benefited from major advances in the recent years, case fatality among people with heart failure remains high worldwide. Hospital case fatality among those with heart failure in Africa ranges from 9% to 12.5%. This consistent death rate ranks heart failure among the major causes of death of cardiovascular origin in Africa.

The clinical presentation of heart failure in Africa is characterized by the high proportion of symptomatic patients. More than 50% of patients present in stage III and IV of the NYHA classification (CitationFofana et al 1988). Clinical signs and symptoms are similar to those reported elsewhere, but are dominated by the high prevalence of nonspecific features (CitationKingue et al 2005). Most clinical studies of heart failure in SSA were conducted in the pre-echocardiographic era or without the application of echocardiography. With recent echocardiographic studies, it is heartening to note that systolic dysfunction, a treatable and preventable form of heart failure is the most frequent cardiac dysfunction found (CitationKingue et al 2005). Most echocardiographic findings are typical findings expected for the various potential underlying aetiologies of heart failure. Three major trends emerge from few studies that have addressed the issue of management of heart failure in SSA: Firstly, underutilization of medications with proven efficacy such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and beta blockers. For example, in a study from Nigeria, only 65% of heart failure patients were on ACEI (CitationAdewole et al 1996). In another study from Cameroon, 19% of patients with heart failure were on beta blockers (CitationKingue et al 2005). Second, when medications are appropriately prescribed, this is not always followed by patient compliance (CitationBhagat and Mazayi-Mupanemunda 2001). Finally, we were unable to identify reports of cardiac resynchronization therapy or ventricular assistant devices and heart transplantation, which are therapeutic options not yet accessible in most African countries.

Heart failure and diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa

Studies from other parts of the world suggest that up to 25% of people with heart failure have diabetes (CitationBauters et al 2003). In the Heart Failure in Israel Survey (HFIS), up to 50% of patients admitted with heart failure had diabetes (CitationGarty et al 2007). Diabetes mellitus has also been recognized to play a key role in the pathogenesis, prognosis, and outcomes of heart failure (CitationSolang et al 1999). Available data from Africa relate to prevalence of diabetes among those with heart failure in hospital retrospective review studies. In the study by CitationThiam and coworkers (2003) in Senegal, 11.8% of heart failure patients had diabetes. In a study of 572 consecutive patients with heart failure in Ghana, 17% of those with coronary artery disease had diabetes (CitationAmoah and Kallen 2000). In a selective group of patients with heart failure in Nigeria, the proportion of those with diabetes was found to be 58% (CitationOla et al 2006). No study has so far directly compared the features of heart failure among people with and without diabetes in SSA.

Determinants of heart failure in diabetes in Africa

Many mechanisms exist to explain the high vulnerability of people with diabetes to heart failure. These include competing cardiovascular risk factors, diabetic specific cardiomyopathy, and other diabetes related risk factors, the accelerated coronary atherosclerosis in diabetes, and in the African setting, the potential interaction between diabetes and other risk factor for heart failure prevalent in SSA.

Classical cardiovascular risk factors

Available evidence supports the view that major cardiovascular risk factors affect the risk of future cardiovascular events in a similar way regardless of diabetes status (CitationKannel and McGee 1979; CitationBalkau et al 1993; CitationAdlerberth et al 1998). However, because most of these risk factors tend to cluster in people with diabetes, the resulting absolute risk of experiencing a cardiovascular event will be much higher among people with diabetes compared with their nondiabetic counterparts (CitationStamler et al 1993). Major risk factors are also consistent across populations and include in addition to diabetes mellitus, age, hypertension and dyslipidemia, smoking, and male gender. Although outcomes studies relating the exposure to these factors to the risk of major cardiovascular events including heart failure are still lacking in SSA for both the general population and people with diabetes, it would be anticipated that the nature of this association will be similar to that reported in other parts of the world. However, the strength of the association may differ at least for some risk factors. For example, in the INTERHEART study, African participants with myocardial infarction were significantly younger compared with participants from other parts of the world (CitationSteyn et al 2005). Similarly, when most of the classical risk factors are considered on their absolute levels, people with diabetes from Africa tend to display different profiles. For instance, the age at onset of type 2 diabetes in Africa is much younger, while people with diabetes from Africa tend to display high prevalence of hypertension (CitationChoukem et al 2007) and prevalence of dyslipidemia, and smoking habits are still low among Africans in general.

Diabetes-related risk factors

Chronic hyperglycemia, insulin resistance and accumulation of collagen and other glycation end-products in the myocardium of people with diabetes are believed to be associated with pathological changes at the level of cardiac myocytes that ultimately result in diabetic cardiomyopathy with increased myocardial stiffness and early abnormal diastolic function. Diabetic cardiomyopathy is characterized by defects of left ventricular function in the absence of significant CAD or systemic hypertension (CitationBell 1995, Citation2003). The condition is associated with important clinical consequences, such as increased susceptibility to hypertension-mediated damage, an increased mortality rate after acute myocardial infarction and progression to symptomatic heart failure (CitationFactor et al 1980; CitationJaffe et al 1984). In addition to diabetic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy and systolic dysfunction that is often asymptomatic and may lead to congestive heart failure have been described in African diabetic patients. Indeed up to 50% of asymptomatic diabetic patients may present with echocardiographic abnormalities (CitationBabalola and Ajayi 1992). However, appropriate comparison of ventricular indexes with matched background nondiabetic population is still lacking. In one of the earliest study of infra-clinical alterations of the left ventricular functions, CitationFamuyiwa and co-workers (1985) compared 89 participants with diabetes with 45 nondiabetic controls, and reached the conclusion that people with diabetes were less vulnerable to vascular complications. However, this study has been contradicted by most recent reports both from Nigeria and elsewhere (CitationMbanya et al 2001; CitationDanbauchi et al 2005). In a study from Cameroon, Mbanya and his colleagues (CitationMbanya et al 2001) found a 40% and 55% prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy and systolic dysfunction among their selective sample of 40 patients with diabetes. This was in keeping with another study from Nigeria in which Danbauchi and his team reported significant sub-clinical cardiomyopathy in people with diabetes (CitationDanbauchi et al 2005). In another recent study among population with hypertension in South Africa, the prevalence of LVH was not different between those with and without type 2 diabetes. In addition, diabetes in this study was not an independent predictor of LVH in multivariate analysis (CitationRayner and Becker 2006). In the midst of these inconsistencies, cardiomyopathy among people with diabetes in Africa deserves further attention, both to clarify the existence and explore underlying pathophysiologic derangements.

Other contributors

Underlying causes of heart failure vary consistently across regions in the world. In SSA, hypertension, valvular heart diseases, and various cardiomyopathies are the dominant causes among adults (CitationSliwa et al 2005; CitationCommerford and Mayosi 2006; CitationOpie 2006). One question is whether there is any interaction between diabetes and other determinants of heart failure mostly found in Africa. In the first analysis, it could be envisaged that diabetes would act at least as a co-factor and may further accelerate the onset of heart failure in patients who are cumulating other risk factors. A controversial role of diabetes as independent risk factor for nonrheumatic valvular disease has been described elsewhere, but not yet in Africa (CitationMovahed et al 2007). However, if confirmed in addition to rheumatic heart disease, already common in Africa, a greater contribution of valvular disease to heart failure would be expected in Africa in the context of the growing burden of diabetes. Anemia, a common finding in individuals with diabetes and particularly those with kidney involvement, may precipitate the unset or exacerbate the already established heart failure in this category of patients. In Africa, even among those without diabetes, anemia is already frequent as a result of infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies (CitationLadipo 1981). Heart failure is rare among pregnant women in Africa and is most often the consequence of valvular heart diseases (CitationAbengowe et al 1980; CitationAggarwal 1980). The congestive phase tends to occur more in the postpartum period and the incidence is not affected by parity and socioeconomic class (CitationAbengowe et al 1980). As a contributor, diabetes has not yet been reported.

Management of heart failure in diabetes

The long-term care of diabetic patients with heart disease poses a particular challenge. Various combinations of risk factors, progression of the coronary heart disease, and complications with further organic damage by the underlying diabetes frequently necessitate a differentiated diagnostic work-up and management.

Control of cardiovascular and diabetes-related risk factors

Compelling evidence from cardiovascular outcomes trials indicates that treatment with drugs that block the rennin – angiotensin system are cardioprotective in diabetics with microalbuminuria and early stages of kidney disease. Multiple risk factor intervention aimed at optimal blood pressure control, lowering LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels, treatment with an ACEI or an angiotensin II receptor blocker, administration of once daily low-dose aspirin and smoking cessation together reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 2 diabetics. Since there is epidemiologic evidence of a relationship between poor metabolic control and development of heart failure (CitationIribarren et al 2001), it would be interesting to evaluate whether aggressive treatment addressing the metabolic consequences of diabetes would improve outcome in diabetic patients with heart failure. However, data on glucose control and heart failure are rare and inconclusive (CitationTang 2006). This is partly due to the lack of trials targeting specifically those with diabetes and heart failure, but also to the poor understanding of the pathophysiologic derangements linking diabetes to heart failure.

Medical treatment of heart failure

Standard medical treatments applied for heart failure in population without diabetes are associated with at least similar beneficial impact in those with diabetes. There remain however some uncertainties about the safety of current antidiabetic medications when used in people with heart failure (CitationFisman et al 2004; CitationSkouri and Wilson Tang 2007). In addition, agents of the thiazolidinedione class may be associated with increased risk of heart failure in people with diabetes (CitationLincoff et al 2007; CitationSingh et al 2007). These medications however are likely to be infrequently used in SSA. Despite the concerns about adverse metabolic effect of beta blockers, available evidence support the view that beta blockers and particularly the nonselective vasodilating ones like carvedilol confer similar survival benefit in heart failure patients with and without diabetes (CitationBell et al 2006). Subgroup analyses from large clinical studies have shown that ACEIs not only reduce mortality in diabetic patients with heart failure, but also reduce the incidence of heart failure in at-risk diabetic patients (CitationVermes et al 2003).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators

Several trials have shown that cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) improves symptoms in patients with advanced heart failure and wide QRS complexes who remain symptomatic in spite of optimal medical therapy (CitationBradley et al 2003). Comparison of effectiveness of CRT in patients with and without diabetes mellitus shows that the benefit of CRT is similar in both groups (CitationKies et al 2005). While ICD do not improve functional outcomes, they do provide substantial mortality benefits by preventing sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure who have an ischemic substrate, poor ejection fraction, and history of ventricular arrhythmias. To our knowledge, no study in SSA has reported results of these novel therapies of heart failure.

Revascularisation

Diabetic patients are known to have reduced long-term survival following percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty compared with nondiabetic patients. This survival disadvantage has persisted over time and can at least in part be explained by the high prevalence of comorbidities among people with diabetes (CitationMathew et al 2004; CitationWilson et al 2004). There are also some controversies regarding the worse post-procedure outcome in insulin-treated patients compared with those on diet or oral agents (CitationMathew et al 2004). However, a difference in the outcome if any should be interpreted in the light of the severity of diabetes and related vascular involvements in insulin-treated type 2 diabetic patients.

Heart transplantation

Heart transplantation is the most indicated treatment for end-stage heart failure, but its impact is limited by the scarcity of donor organs and stringent selection criteria for both donors and recipients. For example, the presence of diabetes complications in the past has limited this approach in people with diabetes. Few data are available to suggest that long-term survival in people with diabetes and diabetes related complications compare to that among their counterparts without complications (CitationMorgan et al 2004; CitationFelker et al 2005; CitationIkeda et al 2007). However, post transplant follow-up face with important diabetogenic effects of classical immunosuppressive drugs. Even when indicated, this treatment option is not widely available in SSA.

Conclusions

One of the earliest documented clinical observations of the syndrome of heart failure originates from Africa (CitationSaba et al 2006). Surprisingly, this disease entity has remained largely unexplored in this part of the world and particularly among the highly vulnerable population with diabetes mellitus. In the general internal medicine service in urban settings, heart failure account for more than 3% of hospital admission, and over 30% among those admitted for cardiovascular diseases. Hypertension, valvular heart diseases, and cardiomyopathies are the main providers of heart failure in SSA, accounting for over 75% of cases in most series. The contribution of diabetes is still ill-studied. However, more than 10% of adults with heart failure also have diabetes. Determinants of heart failure reported elsewhere in people with diabetes are also found among people with diabetes in Africa, but, there are still some inconsistencies about the contribution of diabetic cardiomyopathy. The available pharmacological treatments, such as ACEIs, beta-blockers, and possibly angiotensin receptor blockers, together with a tight glycemic control, as reported elsewhere, must be effective for the treatment of heart failure if adequately used among people with diabetes in Africa.

There is need for more elaborate studies of heart failure in the general population in Africa and in people with diabetes in particular, given their high vulnerability. It is expected that initiatives such as The Heart of Soweto Study (CitationStewart et al 2006) will provide a body of information on heart diseases and therefore heart failure as observed in SSA communities. There is evidence in support of the existing and growing capacity for research on chronic and cardiovascular diseases in SSA (CitationHofman et al 2006). If encouraged and provided with the needed support, their efforts are likely to translate into more insight into heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases in countries of this region.

References

- AbengoweCUDasCKSiddiqueAKCardiac failure in pregnant Northern Nigerian womenInt J Gynaecol Obstet198017467706103844

- AdewoleADIkemRTAdigunAQA three year clinical review of the impact of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors on the intra hospital mortality of congestive heart failure in NigeriansCent Afr J Med19964225358990572

- AdlerberthAMRosengrenAWilhelmsenLDiabetes and long-term risk of mortality from coronary and other causes in middle-aged Swedish men. A general population studyDiabetes Care199821539459571339

- AggarwalVPObstetric emergency referrals to Kenyatta National HospitalEast Afr Med J19805714497371583

- AmoahAGKallenCAetiology of heart failure as seen from a National Cardiac Referral Centre in AfricaCardiology200093111810894901

- APCSCThe effects of diabetes on the risks of major cardiovascular diseases and death in the Asia-Pacific regionDiabetes Care200326360612547863

- AyodeleOEAlebiosuCOSalakoBLTarget organ damage and associated clinical conditions among Nigerians with treated hypertensionCardiovasc J S Afr200516899315915275

- BabalolaROAjayiAAA cross-sectional study of echocardiographic indices, treadmill exercise capacity and microvascular complications in Nigerian patients with hypertension associated with diabetes mellitusDiabet Med199298999031478033

- BalkauBEschwegeEPapozLRisk factors for early death in non-insulin dependent diabetes and men with known glucose tolerance statusBMJ199330729598374376

- BardgettHPDixonMBeechingNJIncrease in hospital mortality from non-communicable disease and HIV-related conditions in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, between 1992 and 2000Trop Doct2006361293116884612

- BautersCLamblinNMc FaddenEPInfluence of diabetes mellitus on heart failure risk and outcomeCardiovasc Diabetol20032112556246

- BellDSDiabetic cardiomyopathy. A unique entity or a complication of coronary artery disease?Diabetes Care199518708148586013

- BellDSDiabetic cardiomyopathyDiabetes Care20032629495114514607

- BellDSLukasMAHoldbrookFKThe effect of carvedilol on mortality risk in heart failure patients with diabetes: results of a meta-analysisCurr Med Res Opin2006222879616466600

- BhagatKMazayi-MupanemundaMCompliance with medication in patients with heart failure in ZimbabweEast Afr Med J20017845811320766

- BradleyDJBradleyEABaughmanKLCardiac resynchronization and death from progressive heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsJAMA20032897304012585952

- ChoukemSPKengneAPDehayemYMHypertension in people with diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: revealing the hidden face of the icebergDiabetes Res Clin Pract200777293917184871

- CommerfordPMayosiBAn appropriate research agenda for heart disease in AfricaLancet20063671884616765744

- DanbauchiSSAnumahFEAlhassanMALeft ventricular function in type 2 diabetes patients without cardiac symptoms in Zaria, NigeriaEthn Dis2005156354016259487

- FactorSMMinaseTSonnenblickEHClinical and morphological features of human hypertensive-diabetic cardiomyopathyAm Heart J198099446586444776

- FamuyiwaOOOdiaOJOsotimehinBONon-invasive cardiac study in diabetic Nigerians using systolic time intervalsTrop Geogr Med19853714394035778

- FelkerGMMilanoCAYagerJEOutcomes with an alternate list strategy for heart transplantationJ Heart Lung Transplant2005241781616297782

- FismanEZTenenbaumAMotroMOral antidiabetic therapy in patients with heart disease. A cardiologic standpointHerz200429290815167955

- FofanaMToureSDadhi BaldeMEtiologic and nosologic considerations apropos of 574 cases of cardiac decompensation in ConakryAnn Cardiol Angeiol (Paris)198837419243190142

- GartyMShotanAGottliebSThe management, early and one year outcome in hospitalized patients with heart failure: a national Heart Failure Survey in Israel – HFSIS 2003Isr Med Assoc J200792273317491211

- HofmanKRyceAPrudhommeWReporting of non-communicable disease research in low- and middle-income countries: a pilot bibliometric analysisJ Med Libr Assoc2006944152017082833

- [IDF] International Diabetes FederationDiabetes Atlas2006BrusselsIDF

- IkedaYTenderichGZittermannAHeart transplantation in insulin-treated diabetic mellitus patients with diabetes-related complicationsTranspl Int2007205283317403108

- IribarrenCKarterAJGoASGlycemic control and heart failure among adult patients with diabetesCirculation200110326687311390335

- IsezuoSASeasonal variation in hospitalisation for hypertension-related morbidities in Sokoto, north-western NigeriaInt J Circumpolar Health20036239740914964766

- JaffeASSpadaroJJSchechtmanKIncreased congestive heart failure after myocardial infarction of modest extent in patients with diabetes mellitusAm Heart J19841083176731279

- KannelWBMcGeeDLDiabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham studyJAMA197924120358430798

- KannelWBMcGeeDLDiabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: the Framingham studyCirculation197959813758126

- KengneAPAmoahAGMbanyaJCCardiovascular complications of diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan AfricaCirculation2005112359260116330701

- KengneAPMbanyaJCDiabetes management in Africa – Challenges and opportunitiesSA J Diabet Vasc Dis200631617

- KiesPBaxJJMolhoekSGComparison of effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with versus without diabetes mellitusAm J Cardiol2005961081115979446

- KingueSDzudieAMenangaAA new look at adult chronic heart failure in Africa in the age of the Doppler echocardiography: experience of the medicine department at Yaounde General HospitalAnn Cardiol Angeiol (Paris)2005542768316237918

- LadipoGOCongestive cardiac failure in elderly Nigerians: a prospective clinical studyTrop Geogr Med198133257626458936

- LincoffAMWolskiKNichollsSJPioglitazone and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized trialsJAMA20072981180817848652

- MagulaNPMayosiBMCardiac involvement in HIV-infected people living in Africa: a reviewCardiovasc J S Afr200314231714610610

- MathewVFryeRLLennonRComparison of survival after successful percutaneous coronary intervention of patients with diabetes mellitus receiving insulin versus those receiving only diet and/or oral hypoglycemic agentsAm J Cardiol20049339940314969610

- MathewVGershBJWilliamsBAOutcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the current era: a report from the Prevention of REStenosis with Tranilast and its Outcomes (PRESTO) trialCirculation20041094768014732749

- MayosiBMContemporary trends in the epidemiology and management of cardiomyopathy and pericarditis in sub-Saharan AfricaHeart20079311768317890693

- MayosiBMBurgessLJDoubellAFTuberculous pericarditisCirculation200511236081616330703

- MbanyaJCKengneAPAssahFDiabetes care in AfricaLancet20063681628917098063

- MbanyaJCSobngwiEMbanyaDSLeft ventricular mass and systolic function in African diabetic patients: association with microalbuminuriaDiabetes Metab2001273788211431604

- MendezGFCowieMRThe epidemiological features of heart failure in developing countries: a review of the literatureInt J Cardiol2001802131911578717

- MensahGABarkeyNLCooperRSSpectrum of hypertensive target organ damage in Africa: a review of published studiesJ Hum Hypertens199487998087853322

- MorganJAJohnRWeinbergADHeart transplantation in diabetic recipients: a decade review of 161 patients at Columbia PresbyterianJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg200412714869215116012

- MotalaAADiabetes trends in AfricaDiabetes Metab Res Rev200218Suppl 3S142012324980

- MovahedMRHashemzadehMJamalMMSignificant increase in the prevalence of non-rheumatic aortic valve disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitusExp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes2007115105717318769

- NjohJComplications of hypertension in adult urban LiberiansJ Hum Hypertens1990488902338699

- OlaBAAdewuyaAOAjayiOERelationship between depression and quality of life in Nigerian outpatients with heart failureJ Psychosom Res20066179780017141668

- OpieLHHeart disease in AfricaLancet20063684495016890828

- OyooGOOgolaENClinical and socio demographic aspects of congestive heart failure patients at Kenyatta National Hospital, NairobiEast Afr Med J19997623710442143

- PanzramGMortality and survival in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitusDiabetologia198730123313556287

- RaynerBBeckerPThe prevalence of microalbuminuria and ECG left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients in private practices in South AfricaCardiovasc J S Afr200617245917117229

- RoglicGUnwinNBennettPHThe burden of mortality attributable to diabetes: realistic estimates for the year 2000Diabetes Care2005282130516123478

- SabaMMVenturaHOSalehMAncient Egyptian medicine and the concept of heart failureJ Card Fail2006124162116911907

- SinghSLokeYKFurbergCDLong-term risk of cardiovascular events with rosiglitazone: a meta-analysisJAMA200729811899517848653

- SkouriHNWilson TangWHThe impact of diabetes on heart failure: opportunities for interventionCurr Heart Fail Rep2007470717521498

- SliwaKDamascenoAMayosiBMEpidemiology and etiology of cardiomyopathy in AfricaCirculation200511235778316330699

- SolangLMalmbergKRydenLDiabetes mellitus and congestive heart failure. Further knowledge neededEur Heart J1999207899510329075

- StamlerJVaccaroONeatonJDDiabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention TrialDiabetes Care199316434448432214

- StewartSWilkinsonDBeckerAMapping the emergence of heart disease in a black, urban population in Africa: the Heart of Soweto StudyInt J Cardiol2006108101816466665

- SteynKSliwaKHawkenSRisk factors associated with myocardial infarction in Africa: the INTERHEART Africa studyCirculation200511235546116330696

- TangWHGlycemic control and treatment patterns in patients with heart failureHeart Fail Monit20065101416547530

- ThiamMCardiac insufficiency in the African cardiology milieuBull Soc Pathol Exot2003962171814582299

- ToureIASalissouOChapkoMKHospitalizations in Niger (West Africa) for complications from arterial hypertensionAm J Hypertens1992532241581014

- VermesEDucharmeABourassaMGEnalapril reduces the incidence of diabetes in patients with chronic heart failure: insight from the Studies Of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD)Circulation20031071291612628950

- WildSRoglicGGreenAGlobal prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030Diabetes Care20042710475315111519

- WilsonSRVakiliBAShermanWEffect of diabetes on long-term mortality following contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: analysis of 4,284 casesDiabetes Care20042711374215111534