Abstract

The wide variety of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents available for clinical use has made choosing the optimal antithrombotic regimen for patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention a complex task. While there is no single best regimen, from a risk-benefit ratio standpoint, particular regimens may be considered optimal for different patients. We review the mechanisms of action for the commonly prescribed antithrombotic medications, summarize pertinent data from randomized trials on their use in acute coronary syndromes, and provide an algorithm (incorporating data from these trials as well as risk assessment instruments) that will help guide the decision-making process.

Introduction

In the early days of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) the armamentarium of antithrombotic agents was limited; therefore, the decision on what agent(s) to administer was fairly straightforward. The wide variety of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents available for clinical use now has made this decision-making process much more complex, and at times even confusing. While there is no single best choice for an antithrombotic regimen in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) undergoing PCI, from a risk-benefit ratio standpoint, a particular regimen may be better for an individual patient. Because early invasive strategies with coronary angiography and PCI are preferred for certain patients with unstable angina, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI),Citation1–Citation4 and STEMI,Citation5 the scope of this issue is considerable. Nearly 8 million people are diagnosed with an ACS annually in the United States alone, and an estimated 1.3 million undergo a PCI procedure.Citation6 Importantly, up to 15% of patients undergoing PCI develop a major bleeding complication,Citation7,Citation8 which results in higher rates of short- and long-term mortality.Citation7,Citation8 The evidence supporting a causal relationship between major bleeding and excess mortality in patients undergoing PCI (including the potential mechanisms involved) has been recently reviewed.Citation9

Decisions on the choice of antithrombotic regimen, therefore, should be individualized, and take into consideration both the risk of a recurrent cardiac event as well as the risk of a bleeding complication. We will review the mechanisms of action for the commonly prescribed antithrombotic medications, summarize pertinent data from randomized trials regarding their use in ACS, and provide an algorithm that will help physicians choose the most effective and safest regimen for an individual patient with an ACS undergoing PCI.

Antithrombotic agents – mechanisms of action

Patients presenting with ACS who undergo PCI benefit from a combination of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications.Citation10 From a pathophysiologic standpoint, the inciting event for an ACS is endothelial injury (plaque rupture or erosion): subsequent activation of platelets and the coagulation cascade results in thrombus formation.Citation11,Citation12 If this process is not interrupted, total occlusion of the coronary artery may occur, resulting in a myocardial infarction. Since platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation comprise the initial stage in thrombus formation, antiplatelet agents (aspirin, thienopyridines, and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) are critically important. Additionally, anticoagulant agents (indirect and direct thrombin inhibitors, and factor Xa inhibitor) also play a key role in the pathophysiologic process by limiting clot formation and propagation, particularly during the PCI procedure itself.

Antiplatelet agents

Antiplatelet medications (aspirin, thienopyridines, and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) are commonly used alone or in combination with other antithrombotic medications in patients with ACS undergoing PCI. We will briefly review their mechanisms of action.

Aspirin

Aspirin permanently and irreversibly blocks cyclooxygenase-1 for the lifespan of the platelet, inhibits the synthesis of thromboxane A2, and is a mainstay of therapy for patients with ACS. It has been shown to improve clinical outcomesCitation13–Citation16 and unless contraindicated, should be administered to all patients with ACS, including those undergoing PCI.

Thienopyridines

Clopidogrel and ticlopidine are structurally related thienopyridines that selectively inhibit adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-induced platelet aggregation. They block the binding of ADP to the receptor P2Y12, thus inhibiting activation of the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex and platelet activation.Citation17 A higher side effect profile of ticlopidine, including diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting in up to 50% of patients,Citation18 and serious hematologic complications such as neutropenia in 1.0% to 2.4% of patients,Citation19 and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpuraCitation20 has led to the primary use of clopidogrel in ACS. Prasugrel, a third generation thienopyridine recently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, is a more potent blocker of the platelet P2Y12 receptor than clopidogrel.Citation21 However, it has also been associated with increased risk of bleeding particularly in patients >75 years of age, in patients who weigh <60 kg, and in those with a history of transient ischemic attacks or strokes.Citation22

Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

Platelet activation leads to a conformational change in the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors bind to and block the conformationally modified receptor, significantly blocking platelet aggregation. These agents can be divided into two groups:Citation23 (1) monoclonal antibodies that block the receptor (abciximab), and (2) natural or synthetic compounds that contain a sequence of amino acids recognized by the receptor that act as competitive inhibitors (tirofiban and eptifibatide). While all three agents are indicated as adjunctive agents in patients undergoing PCI, only eptifibatide and tirofiban are approved for use in patients presenting with a non-STEMI who do not undergo an early invasive strategy.

Anticoagulant agents

Anticoagulant medications are also used alone or in combination with antiplatelet medications in patients with ACS undergoing PCI. These agents include indirect thrombin inhibitors (unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin), direct thrombin inhibitors (bivalirudin), and factor Xa inhibitor (fondaparinux).

Indirect thrombin inhibitors

The heparins, both unfractionated and low molecular weight, are indirect thrombin inhibitors. These agents complex with antithrombin and inhibit fibrin formation, as well as clot production and propagation. Unfractionated heparin has been the primary parenteral anticoagulant used in patients with ACS. It targets the coagulation factors IIa (thrombin) and Xa, with additional but less significant activity against factors IXa, XIa, and XIIa.Citation24 Unfractionated heparin inactivates thrombin by forming a complex with thrombin and anti-thrombin, and inactivates factor Xa through antithrombin. Limitations to unfractionated heparin use include the need for frequent laboratory monitoring, neutralization of heparin’s activity by activated platelets,Citation25 thrombocytopenia,Citation26 platelet aggregation,Citation26 a dose-dependent risk of bleeding,Citation27 and rebound ischemia following its discontinuation.Citation28–Citation30 Moreover, since unfractionated heparin is heterogenous in structure (about one-third of heparin chains contain the high-affinity pentasaccharide required for anticoagulant activity) it is also heterogeneous in its pharmacologic activity. Thus, the efficacy and safety of low-molecular-weight heparin has been studied in patients with ACS as an alternative to unfractionated heparin.

Low-molecular-weight heparins are fragments of unfractionated heparin formed via depolymerization reactions that result in polysaccharides of smaller size. Low-molecular-weight heparin has greater anti-Xa than anti-IIa activity. Importantly, it does not require monitoring of clotting times, is less inhibited by activated platelets,Citation25 and is associated with a lower incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopeniaCitation31 and rebound ischemia following its discontinuation.Citation29 Since it binds less avidly to heparin-binding proteins than does unfractionated heparin, it has better bioavailability and a more predictable anticoagulant response. Of the low-molecular-weight heparins clinically available, enoxaparin is by far the most widely used. It has been shown to decrease ischemic complications in patients treated both conservatively and invasively.Citation32

Direct thrombin inhibitors

The direct thrombin inhibitors, hirudin, argatroban and bivalirudin directly bind to thrombin (factor IIa) without the need for antithrombin. Compared to indirect thrombin inhibitors, they have a more predictable anticoagulant response, do not require anticoagulant monitoring, and are able to inactivate fibrin-bound as well as fluid-phase thrombin.Citation33,Citation34 Importantly, because they do not bind to platelet factor 4, they do not cause heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Hirudin and argatroban are approved for the treatment of patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia;Citation35,Citation36 bivalirudin is approved as an alternative to heparin in patients with ACS and in patients undergoing PCI.

Factor Xa inhibitor

Fondaparinux is a synthetic analog of the antithrombin-binding pentasaccharide sequence found in heparin. It is the only selective factor Xa inhibitor available for clinical use. It binds to and produces a conformational change in antithrombin, markedly increasing its anti-factor Xa activity, but has no activity against thrombin. Fondaparinux does not require monitoring of coagulation, which results in more predictable and sustained anticoagulation compared to heparin. Additionally, since it does not bind to platelets or to platelet factor 4, it does not cause heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Because it is cleared by the kidneys, it is contra-indicated in patients with a CrCl < 30 ml/min. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommends its use for patients with ACS who are undergoing an early invasive or conservative strategy.Citation37 However, in patients undergoing PCI its use has been associated with high rates of catheter thrombosis, making the addition of unfractionated heparin mandatory in this setting.Citation38

Reversal of agents

If a patient does experience a serious bleeding episode, in addition to discontinuation of antithrombotic agents, several antidotes are available for clinical use to help stop the bleeding and stabilize the patient. In patients in whom unfractionated heparin has been given protamine sulfate can be administered. Protamine sulfate is administered intravenously at a rate that should not exceed 50 mg over 10 minutes because of the risk of histamine release resulting in hypotension, bradycardia, and bronchospasm.Citation39 The newer agents including low-molecular-weight heparin, the factor Xa inhibitor, fondaparinux, and the direct thrombin inhibitors do not have specific antidotes. While protamine sulfate is a specific and effective antidote for unfractionated heparin, it only partially neutralizes the anticoagulant effect of low-molecular-weight heparin (approximately 60% of the anticoagulant effect), and therefore its use may result in failure to stop the bleeding.Citation40 Recombinant factor VIIa has been shown to reverse the anticoagulant effect of fondaparinux, however, one important caveat is that this reversal effect was shown in healthy volunteers, not in patients with ACS.Citation41 In experimental models, recombinant factor VIIa, prothrombin complex concentrates, and desmopressin acetate have all been studied as to their ability to reverse the anticoagulant effect of the direct thrombin inhibitors.Citation39 Lastly, hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, and plasmapheresis may be indicated in some cases of severe bleeding.Citation42

Data from the randomized trials

Over the last decade, many randomized trials have been performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of antithrombotic therapies. We will summarize pertinent data regarding their use in patients with ACS undergoing PCI.

Role of thienopyridines

In trials comparing ticlopidine to clopidogrel in combination with aspirin following intracoronary stent placement, clopidogrel was not only as effective as ticlopidine, but had a superior safety and tolerability profile.Citation43–Citation45 These positive findings for clopidogrel, together with the serious risk of neutropenia with ticlopidine,Citation46 has led to the virtual discontinuation of ticlopidine administration: used only in the rare patient who is intolerant to clopidogrel.

It has become increasingly clear that, in addition to aspirin, the early administration of clopidogrel is key since optimal pretreatment with this medication has been shown to significantly influence clinical outcomes in patients with ACS treated both conservativelyCitation47 and invasively.Citation48,Citation49 Hence, clopidogrel carries a Class I (level of evidence: A) indication for all patients with ACS according to the ACC/AHA guidelines.Citation37 Moreover, pretreatment (or lack of pretreatment) with clopidogrel influences the decision as to which antithrombotic regimen to choose for patients undergoing PCI. The original study demonstrating the importance of clopidogrel therapy in patients with ACS undergoing PCI was the PCI-Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) study.Citation48 Of the 2658 patients undergoing PCI in this study, those who were pre-treated with 300 mg of clopidogrel had a 31% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular death or myocardial infarction at long-term (8-month) follow-up compared to those treated with placebo (8.8% vs 12.6%, P = 0.002). Importantly, there was no significant difference in rates of major bleeding between the two groups (2.7% vs 2.5%, P = 0.64). The benefit of clopidogrel administration is also evident in ACS patients who require coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) following diagnostic coronary angiography. An analysis from the Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy (ACUITY) study showed that patients who received clopidogrel prior to CABG had lower rates of the composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or unplanned revascularization at 30 days compared to those who did not receive clopidogrel (12.7% vs 17.3%, P = 0.01).Citation50 Moreover, there was no difference in rates of post-surgical major bleeding (50.3% vs 50.9%, P = 0.83).

In addition to the length of time prior to PCI the loading dose of clopidogrel is administered, the dosage (conventional 300 mg or high dose 600 mg) is also important. It has been shown that some patients exhibit incomplete inhibition of ADP-induced platelet aggregation within 24 hours of a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel.Citation51 Thus, the risks and benefits of administering a higher loading dose of clopidogrel (600 mg) have been examined. In one study, 292 patients were randomized to either a 300 mg or 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel at least 12 hours prior to PCI.Citation52 ADP-induced platelet aggregation was significantly lower in patients who received 600 mg of clopidogrel compared to those who received 300 mg of clopidogrel. Moreover, there were significantly fewer cardiovascular events in the group that received the 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel compared to the 300 mg loading dose (5.0% vs 12.0%, P = 0.02). The benefit of a higher loading dose of clopidogrel was also seen in the Platelet Responsiveness to Aspirin and Clopidogrel and Troponin Increment after Coronary Intervention in Acute Coronary Lesions (PRACTICAL) trial.Citation53 In this trial patients who were randomized to 600 mg of clopidogrel had significantly reduced ADP-induced platelet aggregation compared to those who were randomized to 300 mg. However, there was no difference in clinical outcomes at 6 months – the high rate (69%) of concomitant platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use may have attenuated the effect of the higher loading dose of clopidogrel. The Antiplatelet Therapy for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty (ARMYDA)-2 trial randomized 255 patients undergoing PCI to either a 600 mg loading dose or a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel 4 to 8 hours prior to the procedure.Citation54 The primary endpoint (a 30-day composite of death, myocardial infarction, or target vessel revascularization) was significantly lower in patients who received the high loading dose of clopidogrel compared to those who received the conventional loading dose (4% vs 12%, P = 0.041), and was driven by a significantly lower rate of myocardial infarction: on multivariate analysis the high loading dose of clopidogrel was associated with a 50% risk reduction of infarction (odds ratio [OR] 0.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.15–0.97, P = 0.044).

Prasugrel, a third generation thienopyridine, has been recently studied in patients with acute coronary syndromes in the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON-TIMI)-38 trial.Citation22 In this trial, 13,608 patients with moderate to high risk acute coronary syndromes scheduled to undergo PCI were randomized to prasugrel (60 mg loading dose and a 10 mg daily maintenance dose) or to clopidogrel (300 mg loading dose and a 75 mg daily maintenance dose) for 6 to 15 months. Patients who were randomized to prasugrel were less likely to experience the primary endpoint (a combined endpoint of death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke; 9.9% vs 12.1%, P < 0.001). However, major bleeding (including fatal bleeding) was significantly increased in patients who received prasugrel compared to clopidogrel (2.4% vs 1.8%, P = 0.03). In a prespecified subgroup analysis of patients presenting with STEMI,Citation55 prasugrel treatment again was associated with a significant decrease in the primary endpoint (6.5% vs 9.5%, P = 0.0017), however, there was no difference in rates of major bleeding between patients randomized to prasugrel vs clopidogrel (1.0% vs 1.3%, P = 0.34). Lastly, in a separate substudy of patients who underwent coronary artery stenting, patients who were randomized to prasugrel had significant decreases not only in the primary endpoint (9.7% vs 11.9%, P = 0.0001), but also the rate of stent thrombosis (1.13% vs 2.35%, P < 0.0001).Citation56 The TRITON-TIMI 38 trial is a perfect example of the balancing act between achieving improved ischemic outcomes and decreasing bleeding complications, and underscores the importance of patient selection and individualizing antithrombotic therapy.

Role of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

Abciximab was the first platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor available for clinical use. Several trials showed improved clinical outcomes in patients with ACS undergoing PCI who were treated with abciximab vs control;Citation57–Citation62 however, its use was associated with significant bleeding complications in many of these trials.Citation57,Citation60 Trials assessing the safety and efficacy of tirofiban and integrilin have shown mixed results with no significant differences in clinical outcomes in some,Citation63,Citation64 and improved clinical outcomes in others.Citation65–Citation67

An important complication of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors that limits widespread use of these agents is the increased risk of bleeding.Citation68 Although a meta-analysis of 6 trials, enrolling 31,402 patients with ACS who were not routinely scheduled for early revascularization showed a 9% reduction in the rate of death or myocardial infarction at 30-day follow-up in patients randomized to platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors compared with placebo (10.8% vs 11.8%, OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84–0.98, P = 0.015), major bleeding complications were increased in patients who received them (2.4% vs 1.4%, P < 0.0001).Citation69 One caveat regarding these results is that the improved clinical outcomes provided by these agents were confined to ACS patients with elevated troponin levels.

Questions remain about the choice of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor due to conflicting results from comparative studies. In the Tirofiban and Reopro Give Similar Efficacy Outcomes (TARGET) trialCitation70 the primary endpoint (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days) occurred more frequently in the patients randomized to tirofiban compared to those randomized to abciximab (7.6% vs 6.0%, P = 0.038). However, in the Multicentre Evaluation of Single High Dose Bolus Tirofiban vs Abciximab with Sirolimus-Eluting Stent or Bare Metal Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction (MULTISTRATEGY) trial,Citation71 there was no difference in ST segment resolution between patients treated with abciximab or tirofiban (Relative Risk [RR] 1.02, 97.5% CI 0.958–1.086, P < 0.001 for noninferiority). Moreover, ischemic and bleeding complications were similar between the groups. Lastly, a recent meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing abciximab vs eptifibatide and tirofiban in primary PCI found no significant differences in angiographic, electrocardiographic or clinical outcomes (including bleeding complications) between abciximab and the use of either eptifibatide or tirofiban.Citation72

Because clopidogrel therapy plays a critical therapeutic role in patients with ACS, some investigators have asked whether platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors add sufficient clinical benefit when superimposed upon a background of aspirin, heparin, and clopidogrel. One of the first studies to examine this question was the Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen-Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR-REACT)-2 study.Citation73 This study randomized 2022 high-risk patients with ACS undergoing PCI to either abciximab therapy (bolus + 12-hour infusion) or placebo. Importantly, all patients were optimally pretreated with 600 mg of clopidogrel (at least 2 hours prior to the procedure) in addition to aspirin and unfractionated heparin. There was a 25% relative risk reduction in the primary end point (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or urgent target vessel revascularization occurring within 30 days) in the patients treated with abciximab (8.9% vs 11.9%; RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.58–0.97, P = 0.03). Moreover, there were no differences in rates of major or minor bleeding, or in the need for blood transfusion. However, at 30 days a pre-specified analysis showed that the significant benefit was confined to the patients who had elevated troponin levels, a finding consistent with a previously published meta-analysis.Citation69

In the Early or Late Intervention in Unstable Angina (ELISA)-2 trial, 328 consecutive patients with ACS were randomized to pretreatment with dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel 600 mg) or triple antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel 300 mg, and tirofiban).Citation74 The primary endpoint was enzymatic infarct size, with a prespecified secondary endpoint of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow on the initial angiogram. Although rates of TIMI 3 flow on the initial angiogram were significantly higher in patients who were treated with triple antiplatelet therapy (67 vs 47%, P = 0.002), there was no difference in the primary endpoint of enzymatic infarct size (median, interquartile range): 166 IU/L (60–349) in the triple antiplatelet group vs 193 IU/L (75–466) in the dual antiplatelet group, P = 0.2. Additionally, there was no significant difference in bleeding rates between the groups.

More recently, the Early Versus Delayed, Provisional Eptifibatide in Acute Coronary Syndromes (EARLY-ACS) trial compared the safety and efficacy of early, routine administration of eptifibatide (2 boluses and a 12-hour infusion prior to angiography) to delayed, provisional administration of eptifibatide in 9492 patients with unstable angina or non-STEMI who were undergoing PCI.Citation75 Importantly, 75% of the patients were pretreated with 300 mg of clopidogrel. There was no difference in the primary endpoint (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, recurrent ischemia requiring urgent revascularization, or the occurrence of a thrombotic complication during PCI that required bolus therapy opposite to the initial study group assignment at 96 hours) between the groups (9.3% in the early eptifibatide group, and 10.0% in the delayed eptifibatide group, OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80–1.06, P = 0.23). Moreover, there was no difference in the rate of death or myocardial infarction at 30 days between the early and delayed eptifibatide groups, with or without the presence of troponin elevation. However, patients randomized to early eptifibatide had a statistically significant increase in TIMI major hemorrhage (2.6% vs 1.8%, P = 0.02), and an increased need for blood transfusions (8.6% vs 6.7%, P = 0.001). Thus, these results indicate that the routine early administration of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with unstable angina and non-STEMI prior to PCI is not recommended. Moreover, in non-STEMI patients who are optimally pre-treated with clopidogrel, the addition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors is unlikely to add significant clinical benefit. Hence, the ACC/AHA guidelines state that for non-STEMI patients in whom an initial invasive approach is selected, it is reasonable to omit the upstream use of a platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor if bivalirudin is used and if at least 300 mg of clopidogrel was administered at least 6 hours prior to the planned procedure (Class IIa, level of evidence: B).Citation37

The data supporting the addition of upstream platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors to high dose clopidogrel in patients presenting with STEMI is conflicting. In the Bavarian Reperfusion Alternatives Evaluation (BRAVE) 3 trial,Citation76 8000 patients with STEMI received a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel and were then randomized to upstream abciximab or placebo prior to PCI. There was no difference in the primary endpoint of infarct size between the two groups. Moreover, there was no difference in the composite endpoint of death, recurrent infarction, stroke, or urgent revascularization between those randomized to abciximab compared to placebo (5.0% vs 3.8%, P = 0.40). In the Ongoing Tirofiban in Myocardial Evaluation (On-TIME) 2 trial,Citation65 984 patients with STEMI were randomized to either a high-dose bolus of tirofiban or placebo in addition to high dose clopidogrel (600 mg), aspirin, and heparin. Patients who were pretreated with tirofiban had significantly better ST segment resolution compared to those who received placebo. The combined endpoint of death, recurrent infarction, urgent target vessel revascularization, or blinded bail-out use of tirofiban was significantly decreased in those who received tirofiban compared to placebo (26.0% vs 32.9%, P = 0.020), suggesting that further platelet inhibition in addition to high dose clopidogrel is important in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI.

In order to decrease the rates of bleeding complications while still benefiting from their use, several studies have evaluated alternate ways to administer platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. One such study called the Brief Infusion of Eptifibatide Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (BRIEF-PCI) trial examined whether an abbreviated infusion of eptifibatide was safe following a successful, non-emergent PCI.Citation77 A total of 624 patients with stable angina, unstable angina, or recent STEMI who underwent successful stenting were randomized to either the standard 18-hour infusion of eptifibatide following the procedure, or an abbreviated infusion of <2 hours. The primary endpoint (the incidence of periprocedural myonecrosis defined as troponin I elevation >0.26 μg/L) was similar between the groups (30.1% in the <2-hour group vs 28.3% in the 18-hour group, P < 0.012 for noninferiority). Moreover, the secondary endpoint (30 day incidence of myocardial infarction, death, and target vessel revascularization) was similar between the two groups (4.5% vs 4.8%, P = 1.0). Importantly, from a risk-benefit ratio standpoint, the abbreviated infusion (<2-hour) resulted in significantly decreased rates of major bleeding complications compared to the standard 18-hour infusion (1.0% vs 4.2%, P = 0.02).

The short-term effects of bolus-only administration of abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide have also been studied.Citation78–Citation82 These studies have suggested that bolus-only platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are as effective as the standard bolus and infusion protocol, but are associated with better clinical outcomes. Additional trials assessing the role (and perhaps length of administration) of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in ACS patients undergoing PCI in the setting of clopidogrel pretreatment are needed.

Role of heparin

The benefit of using unfractionated heparin in the treatment of ACS was first documented more than 20 years ago,Citation83 and subsequently, its use has been shown to result in a 33% relative risk reduction in death or myocardial infarction when prescribed in addition to aspirin.Citation84 In patients with ACS undergoing an initial invasive strategy, both unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin carry a Class I indication (level of evidence: A).Citation37 However, the limitations of unfractionated heparin as described above have led investigators to explore the use of low-molecular-weight heparin instead. One of the first studies to evaluate low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with ACS was the Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q Wave Coronary Events Study Group (ESSENCE) trial.Citation85 The ESSENCE trial compared the use of the low-molecular-weight heparin, enoxaparin, to unfractionated heparin in patients with ACS undergoing PCI. Patients randomized to enoxaparin had lower rates of the composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or recurrent angina compared to patients treated with unfractionated heparin at 14 days (16.6% vs 19.8%, P = 0.019), and at 30 days (27.9% vs 32.2%, P = 0.001). Moreover, this benefit was maintained at 1-year follow-up (32.0% vs 35.7%, P = 0.002).Citation29 The TIMI-IIb trial confirmed the benefit of enoxaparin in patients with ACS.Citation86 There was a significant reduction in the primary endpoint (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or urgent revascularization at 8 days and at 43 days) in patients treated with enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin (12.4% vs 14.5%, P = 0.048). A meta-analysis combining data from both the ESSENCE and TIMI-IIb trials showed a reduction in death and ischemic events for patients receiving enoxaparin at day 8 (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.62–0.95, P = 0.02), which persisted through follow-up at 14 days (OR 0.79, 95%CI 0.65–0.96, P = 0.02) and at 43 days (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69–0.97, P = 0.02).Citation87

The more recent Superior Yield of the New Strategy of Enoxaparin, Revascularization and Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (SYNERGY) trial which randomized 10,027 high-risk patients with non-STEMI to either enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin prior to an early invasive approach, found no significant difference in the primary endpoint of all-cause death or nonfatal myocardial infarction during the first 30 days after randomization between the groups (14.0% vs 14.5%, P = NS).Citation88 While no differences in the rates of bleeding have been reported in patients receiving unfractionated vs enoxaparin who undergo an initial conservative approach,Citation89,Citation90 the SYNGERY trial reported an increase in TIMI major bleeding in patients receiving enoxaparin (9.1% vs 7.6%, P = 0.008).Citation88 A meta-analysis comparing unfractionated heparin to low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with ACS revealed no significant difference in the risk of major bleeding with the short-term use of both unfractionated heparin vs placebo (OR 1.88, 95% CI 0.60–5.87, P = 0.28) and low molecular weight vs placebo (OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.62–3.23). However, long-term use of unfractionated heparin was associated with a significant increase in major bleeding (OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.63–3.14, P < 0.0001) which was equivalent to an excess of 12 major bleeds for every 1000 patients treated.Citation90 Pooled data from 21,946 patients in 6 trials comparing unfractionated heparin to low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with ACS showed no significant difference in death at 30 days for enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin (3.0% vs 3.0%, OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.85–1.17).Citation91 However, the combined endpoint of death or nonfatal infarction at 30 days was significantly lower for patients treated with enoxaparin rather than unfractionated heparin (10.1% vs 11.0%, OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83–0.99). Importantly, there was no significant difference in rates of blood transfusions (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.89–1.14) or major bleeding (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.83–1.30) at 7 days after randomization.

Nonetheless, the inability to measure the level of anticoagulant therapy with the activated clotting time in patients receiving low-molecular weight-heparin generates reluctance by interventional cardiologists to use it during PCI. The widespread use of low-molecular-weight heparin in ACS patients before angiography, however, makes this issue unavoidable. Guidelines for the use of enoxaparin in the peri-PCI period have been proposed.Citation37,Citation92 These guidelines state that if enoxaparin is to be used as the antithrombotic agent during the PCI procedure, no additional amount should be given if the last dose was administered within 8 hours. If the last subcutaneous dose was administered at least 8 to 12 hours earlier, an intravenous dose of 0.3 mg/kg of enoxaparin should be given. An 8-hour window after the last dose of low-molecular-weight heparin is preferred prior to switching to unfractionated heparin.Citation93

A unique treatment strategy using low dose enoxaparin (0.50 mg/kg every 12 hours) prior to PCI in conjunction with dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) followed by triple antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel and eptifibatide) during the PCI has been evaluated in a large, single center study.Citation94 The analysis included 1400 consecutive patients and found that this treatment strategy was associated with low rates of acute ischemic events (1.8%), minor bleeding complications (2.1%), major bleeding complications (0.1%), thrombocytopenia (1.3%), and major adverse clinical events (0.4%); suggesting the need for a randomized clinical trial to further evaluate this approach.Citation94

Despite improved bioavailability and predictable weight-based dosing, there are several patient populations where pharmacologic parameters for low-molecular-weight heparin are altered including patients with renal insufficiency, the elderly, and the obese.Citation95 Patients who are obese have less lean body mass as a percentage of total body weight, so dosing low-molecular-weight heparin according to total body weight can cause supra-therapeutic anticoagulation. A similar problem arises in the elderly who also have less lean body mass (in addition to other complicating factors such as renal insufficiency). Since the kidneys are the primary route of elimination for low-molecular-weight heparin, patients with impaired renal function, particularly with CrCl < 30 ml/min are at risk for accumulation of the drug, increased levels of anti-Xa, and increased risk of major bleeding complications.Citation96,Citation97 In general, the use of low-molecular-weight heparin should be avoided in patients with CrCl < 30 ml/min.

Role of factor Xa inhibitor

The safety and efficacy of the novel factor Xa inhibitor, fondaparinux, was evaluated in the Organization to Assess Strategies in Acute Ischemic Syndromes (OASIS)-5 trial.Citation38 In this trial 20,078 patients with unstable angina or non-STEMI were randomized to enoxaparin 1.0 mg/kg every 12 hours or to fondaparinux 2.5 mg daily. The primary outcome (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or refractory ischemia at 9 days) occurred in 5.7% of those randomized to enoxaparin and 5.8% of those randomized to fondaparinux (hazard ratio 1.01, 95% CI 0.90–1.13, P = 0.007 for noninferiority). Moreover, major bleeding complications were significantly less in the patients receiving fondaparinux (2.2% vs 4.1%, P < 0.001). However, in the patients who underwent PCI, those who were treated with fondaparinux had a significant increase in rates of catheter thrombosis compared to those treated with enoxaparin (0.9% vs 0.4%, P = 0.001) which was believed to be from the inability of fondaparinux to block pre-existing thrombin. Therefore, because of the risk of catheter thrombosis, fondaparinux should not be used as the sole anticoagulant during PCI in patients with STEMI (Class III indication, level of evidence: C); unfractionated heparin should be concomitantly administered.Citation98

The use of fondaparinux in patients with non-STEMI and unstable angina who undergo both an initial conservative or invasive management strategy carries a Class I indication (level of evidence: B) according to the ACC/AHA guidelines.Citation37 Similar to low-molecular-weight heparin, fondaparinux is excreted by the kidneys and therefore is contraindicated in patients with a CrCl < 30 ml/min.Citation37

Role of bivalirudin

In addition to low-molecular-weight heparin, bivalirudin has also been studied as a replacement for unfractionated heparin in patients with ACS undergoing PCI and carries a Class I (level of evidence:B) indication for use in these patients.Citation37 One of the first studies to evaluate the use of bivalirudin in PCI randomized 4098 patients to receive either unfractionated heparin or bivalirudin during the procedure.Citation99 While there was no difference in the primary endpoint (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, abrupt vessel closure, or rapid clinical deterioration of cardiac origin), patients randomized to bivalirudin had significantly lower rates of bleeding compared to patients randomized to unfractionated heparin (3.8% vs 9.8%, P < 0.001).

With the introduction of more potent antiplatelet agents like clopidogrel and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, several trials have examined the safety and efficacy of bivalirudin in conjunction with these medications. In a pilot trial called the Comparison of Abciximab Complications with Hirulog for Ischemic Events (CACHET) trial, 268 patients were randomized to receive bivalirudin (with or without abciximab) or abciximab with low-dose weight-adjusted heparin during PCI.Citation100 In this study, bivalirudin with planned or provisional abciximab was as safe and effective as low-dose heparin plus abciximab. In a separate trial called the Protection against Post-PCI Microvascular Dysfunction and Post-PCI Ischemia among Anti-Platelet and Anti-Thrombotic Agents-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (PROTECT-TIMI)-30 trial, 857 patients with non-STEMI were randomized to one of three regimens following angiography: eptifibatide + reduced-dose unfractionated heparin, eptifibatide + reduced dose low-molecular-weight heparin, or bivalirudin mono-therapy.Citation101 The primary endpoint, coronary flow reserve, was greater in the bivalirudin arm compared to pooled data from the two different eptifibatide arms (1.43 vs 1.33, P = 0.036). However, TIMI myocardial perfusion grade was more often normal in patients treated with eptifibatide compared to bivalirudin (57.9% vs 50.9%, P = 0.048), and the duration of ischemia on Holter monitoring after PCI was significantly longer in patients treated with bivalirudin (169 min vs 36 min, P = 0.013). Although there was no excess of TIMI major bleeding in patients treated with eptifibatide compared with bivalirudin (0.7% vs 0%, P = NS), TIMI minor bleeding was increased (2.5% vs 0.4%, P = 0.027) as well as blood transfusion requirements (4.4 % vs 0.5%, P < 0.001).

The ACUITY study examined the use of bivalirudin in 13,819 moderate-risk and high-risk patients with ACS undergoing an early invasive strategy.Citation102 Patients were randomized to one of three regimens: platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor + unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin; platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa + bivalirudin; or bivalirudin alone. Bivalirudin + platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, as compared to heparin + platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, was associated with similar rates of the composite ischemic endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or unplanned revascularization (7.7% vs 7.3%, P = NS); major bleeding (5.3% vs 5.7%, P = NS); and the net clinical endpoint of ischemia or major bleeding (11.8% vs 11.7%, P = NS). In addition, bivalirudin alone, as compared to heparin + platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, was associated with similar rates of the composite ischemic endpoint (7.8% vs 7.3%, P = 0.32), and significantly reduced rates of major bleeding (3.0% vs 5.7%, P < 0.001), and the net clinical endpoint (10.1% vs 11.7%, P = 0.02). In a subgroup analysis of this trial that evaluated 7789 patients who underwent PCI, there were no differences in the composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, unplanned revascularization, or death at one year.Citation103 However, there was a significant reduction in major bleeding in those patients who received bivalirudin alone compared to those who received heparin + platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (4.0% vs 7.0%, P < 0.001). In a separate analysis of the ACUITY trial, patients who were switched to bivalirudin from either unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin had similar rates of ischemia (6.9% vs 7.4%, P = 0.52), but less major bleeding complications (2.8% vs 5.8%, P < 0.01), which resulted in improved net clinical outcomes (9.2% vs 11.9%, P < 0.01) compared to those who remained on unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin + platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.Citation104

Lastly, the Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial randomized 3602 patients with STEMI to heparin + platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa or bivalirudin alone.Citation105 Anticoagulation with bivalirudin was associated with a 24% absolute risk reduction in the net adverse clinical events (major bleeding or major adverse cardiac events including death, re-infarction, target vessel revascularization for ischemia, and stroke) at 30 days (9.2% vs 12.1%, RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.63–0.92, P = 0.0005) with a 40% absolute reduction in major bleeding (4.9% vs 8.3%, RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.46–0.77, P < 0.001). One important caveat regarding the results of this trial is that there was an increased risk of acute stent thrombosis within 24 hours in patients treated with bivalirudin (0.3% vs 1.3%, P < 0.001). It has been suggested that one contributing factor could have been inadequate pretreatment with clopidogrel. This concern was addressed in a post-hoc analysis of the 7789 patients in the ACUITY trial that underwent PCI:Citation106 when clopidogrel was administered prior to the PCI or within 30 minutes after the PCI, bivalirudin therapy alone was associated with similar ischemic outcomes compared to placebo (8.2% vs 8.3%, RR 0.98, 95% CL 0.81–1.20, P = 0.88). However, in patients who received clopidogrel either >30 minutes after the PCI or not at all, there was a significant increase in ischemic events in patients randomized to bivalirudin compared to placebo (14.1% vs 8.5%, RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.05–2.63, P = 0.03).

The prevailing theme of the importance of optimal clopidogrel pretreatment is also evident in trials assessing the safety and efficacy of bivalirudin in patients with ACS undergoing PCI.Citation107,Citation108 In the Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR-REACT) 3 study,Citation107 the use of bivalirudin in patients with stable or unstable angina undergoing PCI was evaluated. In this trial 4570 patients who were optimally pretreated with 600 mg of clopidogrel were randomized to either bivalirudin or unfractionated heparin at the time of the PCI procedure. While there was no difference in the primary endpoint (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, and target vessel revascularization due to myocardial ischemia at 30 days), there was a lower incidence of major bleeding in the bivalirudin group (4.6% vs 3.1%, P = 0.0008). In the Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events (REPLACE)-2 trial 6010 patients undergoing elective or urgent PCI were randomized to bivalirudin with provisional platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, or to heparin with planned platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor.Citation108 Importantly, greater than 84.9% of patients received pre-treatment with clopidogrel (26.6% received clopidogrel <2 hours prior to PCI and 56.7% received it between 2–48 hours prior of PCI). Similar to the ISAR-REACT 3 study, there was no difference in the primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or urgent repeat revascularization at 30 days, and in-hospital major bleeding rates were significantly less with bivalirudin than the combination of heparin and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (2.4% vs 4.1%, P < 0.001).

What agents should be used?

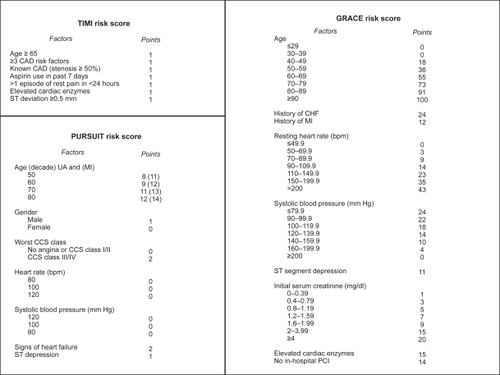

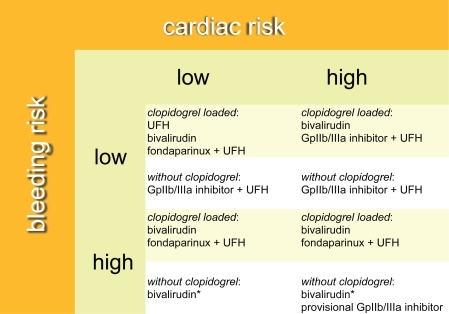

The combination of a large variety of antithrombotic medications available (), and the lack of consensus regarding the optimal regimen for any given patient, has resulted in a long list of potential regimens. There must be a balance between choosing the regimen that will minimize the risk of recurrent ischemic events, and one that will minimize the risk of bleeding.Citation9 Considering the overall risk-benefit ratio, therefore, is important in the decision-making process since it may guide the physician to choose one particular antithrombotic regimen over another for any given patient.Citation109 Several risk assessment algorithms are available to help the physician gauge whether the patient is at high- or low-risk for a recurrent cardiac event including the TIMI risk score,Citation110 the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score,Citation111 and the Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in Unstable Angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin Therapy (PURSUIT)Citation112 (). In addition to the risk of a recurrent ischemic event, there are other important factors that should be taken into consideration (): (1) the risk of bleeding, (2) the timing and dose of clopidogrel prior to PCI (if administered), (3) the timing and dose of low-molecular-weight heparin prior to PCI (if administered), (4) the patient’s renal function, and (5) whether the patient has a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or previous drug reactions.

Figure 1 The TIMI, PURSUIT, and GRACE risk scores.

Table 1 Antithrombotic agents commonly administered to patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention

Table 2 Key considerations in selecting the optimal antithrombotic regimen for an individual patient

Recently, the Can Rapid Risk stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines (CRUSADE) bleeding score has been developed and validated.Citation113 This score predicts the baseline risk of in-hospital major bleeding and incorporates patient information that is readily available upon admission: patient factors predictive of in-hospital major bleeding are female gender, diabetes, a history of vascular disease, high or low systolic blood pressure, tachycardia, hematocrit <36%, and renal insufficiency. Advanced age has also been shown to be a risk factor for major bleeding complications.Citation114 However, since no current algorithm incorporates both ischemic and bleeding risk, creation of a “bleeding risk subscale” has been proposed.Citation115 Moreover, these investigators recommend particular anthithrombotic agents by integrating bleeding risk with specified ranges of the TIMI, PURSUIT, and GRACE risk scores that define patients at low (defined as TIMI 0–2, PURSUIT 0–8, GRACE 0–124); moderate (defined as TIMI 3–4, PURSUIT 9–16, GRACE 125–248); and high (defined as TIMI 5–7, PURSUIT 17–25, GRACE 249–372) ischemic risk. We similarly propose an algorithm, but include not only cardiac and bleeding risk, but also whether the patient has been pretreated with clopidogrel (). In patients who are pretreated with clopidogrel, there are many acceptable choices for an antithrombotic regimen during PCI, especially when the bleeding risk is low. The more difficult scenario, however, is when the patient has not been pretreated with clopidogrel, and is at high risk for a bleeding complication: in this case, if bivalirudin is used, a loading dose of clopidogrel should be administered as soon as possible in the cardiac catheterization laboratory to decrease the risk of subacute stent thrombosis. Moreover, if a platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor is needed on a provisional basis, a short-acting agent would be preferable.

Figure 2 Algorithm for selecting the optimal antithrombotic regimen incorporating cardiac risk, bleeding risk, and clopidogrel pretreatment. In this algorithm it is assumed that all patients have received aspirin.

*If bivalirudin is used, a loading dose of clopidogrel should be given as soon as possible in the cardiac catheterization laboratory to decrease the risk of subacute stent thrombosis.

Future prospects

Novel agents primarily used for prevention of venous thromboembolism are currently being investigated for use in patients with ACS.Citation116 In the Anti-Xa Therapy to Lower Cardiovascular Events in Addition to Aspirin with or without Thienopyridine Therapy in Subjects with Acute Coronary Syndrome-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (ATLAS ACS-TIMI) 46 trial, rivaroxaban (an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor) was associated with a dose-dependent increase in clinically significant bleeding events, with a trend towards a reduction in the primary efficacy endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or severe recurrent ischemia requiring revascularization.Citation117 Similar findings have been published regarding apixaban, also an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor evaluated in the Apixaban for Prevention of Acute Ischemic Events (APPRAISE) trial.Citation118 Lastly, dabigatron, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor is being studied in the context of secondary prophylaxis after myocardial infarction in the placebo-controlled phase II Randomized Dabigatron Dose Finding Study in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Post Index Event with Additional Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Complications Also Receiving Aspirin and Clopidogrel: Multi-Centre, Prospective, Placebo Controlled, Cohort Dose Escalation (RE-DEEM) trial.Citation119

Conclusion

Selecting the appropriate antithrombotic regimen for patients with ACS undergoing PCI has become a complex task. Treatment guidelines are needed to help physicians incorporate cardiac risk, bleeding risk, and other key factors into their selection of the optimal antithrombotic regimen for an individual patient.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Invasive compared with non-invasive treatment in unstable coronary-artery disease: FRISC II prospective randomised multicentre studyFRagmin and Fast Revascularisation during InStability in Coronary artery disease InvestigatorsLancet1999354918070871510475181

- SabatineMSMorrowDAGiuglianoRPImplications of upstream glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition and coronary artery stenting in the invasive management of unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a comparison of the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) IIIB trial and the Treat angina with Aggrastat and determine Cost of Therapy with Invasive or Conservative Strategy (TACTICS)-TIMI 18 trialCirculation2004109787488014757697

- FoxKAPoole-WilsonPAHendersonRAInterventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Randomized Intervention Trial of unstable AnginaLancet2002360933574375112241831

- NeumannFJKastratiAPogatsa-MurrayGEvaluation of prolonged antithrombotic pretreatment (“cooling-off ” strategy) before intervention in patients with unstable coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2003290121593159914506118

- KeeleyECBouraJAGrinesCLPrimary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trialsLancet20033619351132012517460

- Lloyd-JonesDAdamsRCarnethonMHeart disease and stroke statistics – 2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics SubcommitteeCirculation20091193e21e18119075105

- FuchsSKornowskiRTeplitskyIMajor bleeding complicating contemporary primary percutaneous coronary interventions-incidence, predictors, and prognostic implicationsCardiovasc Revasc Med2009102889319327670

- KinnairdTDStabileEMintzGSIncidence, predictors, and prognostic implications of bleeding and blood transfusion following percutaneous coronary interventionsAm J Cardiol200392893093514556868

- DoyleBJRihalCSGastineauDAHolmesDRJrBleeding, blood transfusion, and increased mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: implications for contemporary practiceJ Am Coll Cardiol200953222019202719477350

- KingSB3rdSmithSCJrHirshfeldJWJr2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice guidelinesJ Am Coll Cardiol200851217220918191745

- FalkEShahPKFusterVCoronary plaque disruptionCirculation19959236576717634481

- FusterVMorenoPRFayadZACortiRBadimonJJAtherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: part I: evolving conceptsJ Am Coll Cardiol200546693795416168274

- Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patientsBMJ20023247329718611786451

- CairnsJAGentMSingerJAspirin, sulfinpyrazone, or both in unstable angina. Results of a Canadian multicenter trialN Engl J Med198531322136913753903504

- LewisHDJrDavisJWArchibaldDGProtective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina Results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative StudyN Engl J Med198330973964036135989

- WallentinLCAspirin (75 mg/day) after an episode of unstable coronary artery disease: long-term effects on the risk for myocardial infarction, occurrence of severe angina and the need for revascularization. Research Group on Instability in Coronary Artery Disease in Southeast SwedenJ Am Coll Cardiol1991187158715931960301

- FosterCJProsserDMAgansJMMolecular identification and characterization of the platelet ADP receptor targeted by thienopyridine antithrombotic drugsJ Clin Invest2001107121591159811413167

- QuinnMJFitzgeraldDJTiclopidine and clopidogrelCirculation1999100151667167210517740

- HaushoferAHalbmayerWMPracharHNeutropenia with ticlopidine plus aspirinLancet199734990504744759040584

- BennettCLWeinbergPDRozenberg-Ben-DrorKYarnoldPRKwaanHCGreenDThrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with ticlopidine. A review of 60 casesAnn Intern Med199812875415449518398

- WiviottSDTrenkDFrelingerALPrasugrel compared with high loading- and maintenance-dose clopidogrel in patients with planned percutaneous coronary intervention: the Prasugrel in Comparison to Clopidogrel for Inhibition of Platelet Activation and Aggregation-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 44 trialCirculation2007116252923293218056526

- WiviottSDBraunwaldEMcCabeCHPrasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromesN Engl J Med2007357202001201517982182

- BerkowitzSDCurrent knowledge of the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists for the treatment of coronary artery diseaseHaemostasis200030Suppl 3274311182626

- HirshJAnandSSHalperinJLFusterVGuide to anticoagulant therapy: Heparin: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart AssociationCirculation2001103242994301811413093

- MelandriGSempriniFCerviVComparison of efficacy of low molecular weight heparin (parnaparin) with that of unfractionated heparin in the presence of activated platelets in healthy subjectsAm J Cardiol19937254504548394644

- ShantsilaELipGYChongBHHeparin-induced thrombocytopenia. A contemporary clinical approach to diagnosis and managementChest200913561651166419497901

- MelloniCAlexanderKPChenAYUnfractionated heparin dosing and risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromesAm Heart J2008156220921518657648

- BahitMCTopolEJCaliffRMReactivation of ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: results from GUSTO-IIb. Gobal Use of Strategies To Open occluded arteries in acute coronary syndromesJ Am Coll Cardiol20013741001100711263599

- GoodmanSGBarrASobtchoukALow molecular weight heparin decreases rebound ischemia in unstable angina or non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: the Canadian ESSENCE ST segment monitoring substudyJ Am Coll Cardiol20003651507151311079650

- TherouxPWatersDLamJJuneauMMcCansJReactivation of unstable angina after the discontinuation of heparinN Engl J Med199232731411451608405

- WarkentinTELevineMNHirshJHeparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients treated with low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparinN Engl J Med199533220133013357715641

- Schmidt-LuckeCSchultheissHPEnoxaparin injection for the treatment of high-risk patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromeVasc Health Risk Manag20073222122817580732

- AroraUKDhirMDirect thrombin inhibitors (part 1 of 2)J Invasive Cardiol2005171343815640538

- AroraUKDhirMDirect thrombin inhibitors (part 2 of 2)J Invasive Cardiol2005172859115687531

- A comparison of recombinant hirudin with heparin for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes. The Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) IIb investigatorsN Engl J Med1996335117757828778585

- Effects of recombinant hirudin (lepirudin) compared with heparin on death, myocardial infarction, refractory angina, and revascularisation procedures in patients with acute myocardial ischaemia without ST elevation: a randomised trial. Organisation to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Syndromes (OASIS-2) InvestigatorsLancet199935391514294389989712

- AndersonJLAdamsCDAntmanEMACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency MedicineCirculation20071167e148e30417679616

- YusufSMehtaSRChrolaviciusSComparison of fondaparinux and enoxaparin in acute coronary syndromesN Engl J Med2006354141464147616537663

- SchulmanSBijsterveldNRAnticoagulants and their reversalTransfus Med Rev2007211374817174219

- CrowtherMABerryLRMonaglePTChanAKMechanisms responsible for the failure of protamine to inactivate low-molecular-weight heparinBr J Haematol2002116117818611841415

- BijsterveldNRMoonsAHBoekholdtSMAbility of recombinant factor VIIa to reverse the anticoagulant effect of the pentasaccharide fondaparinux in healthy volunteersCirculation2002106202550255412427650

- CrowtherMAWarkentinTEBleeding risk and the management of bleeding complications in patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy: focus on new anticoagulant agentsBlood2008111104871487918309033

- BertrandMERupprechtHJUrbanPGershlickAHDouble-blind study of the safety of clopidogrel with and without a loading dose in combination with aspirin compared with ticlopidine in combination with aspirin after coronary stenting: the clopidogrel aspirin stent international cooperative study (CLASSICS)Circulation2000102662462910931801

- MullerCButtnerHJPetersenJRoskammHA randomized comparison of clopidogrel and aspirin versus ticlopidine and aspirin after the placement of coronary-artery stentsCirculation2000101659059310673248

- TaniuchiMKurzHILasalaJMRandomized comparison of ticlopidine and clopidogrel after intracoronary stent implantation in a broad patient populationCirculation2001104553954311479250

- GentMBlakelyJAEastonJDThe Canadian American Ticlopidine Study (CATS) in thromboembolic strokeLancet198918649121512202566778

- YusufSZhaoFMehtaSRChrolaviciusSTognoniGFoxKKEffects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevationN Engl J Med2001345749450211519503

- MehtaSRYusufSPetersRJEffects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE studyLancet2001358928152753311520521

- SteinhublSRBergerPBMannJT3rdEarly and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2002288192411242012435254

- EbrahimiRDykeCMehranROutcomes following pre-operative clopidogrel administration in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY) trialJ Am Coll Cardiol200953211965197219460609

- GurbelPABlidenKPHiattBLO’ConnorCMClopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pre-treatment platelet reactivityCirculation2003107232908291312796140

- CuissetTFrereCQuiliciJBenefit of a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel on platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary stentingJ Am Coll Cardiol20064871339134517010792

- YongGRankinJFergusonLRandomized trial comparing 600- with 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the Platelet Responsiveness to Aspirin and Clopidogrel and Troponin Increment after Coronary intervention in Acute coronary Lesions (PRACTICAL) TrialAm Heart J2009157160 e61e6919081397

- PattiGColonnaGPasceriVPepeLLMontinaroADi SciascioGRandomized trial of high loading dose of clopidogrel for reduction of periprocedural myocardial infarction in patients undergoing coronary intervention: results from the ARMYDA-2 (Antiplatelet therapy for Reduction of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty) studyCirculation2005111162099210615750189

- MontalescotGWiviottSDBraunwaldEPrasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trialLancet2009373966572373119249633

- WiviottSDBraunwaldEMcCabeCHIntensive oral antiplatelet therapy for reduction of ischaemic events including stent thrombosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with percutaneous coronary intervention and stenting in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial: a subanalysis of a randomised trialLancet200837196211353136318377975

- Use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor in high-risk coronary angioplasty. The EPIC InvestigationN Engl J Med1994330149569618121459

- Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade and low-dose heparin during percutaneous coronary revascularization. The EPILOG InvestigatorsN Engl J Med199733624168916969182212

- Randomised placebo-controlled and balloon-angioplasty-controlled trial to assess safety of coronary stenting with use of platelet glycoprotein-IIb/IIIa blockadeLancet1998352912287929672272

- BrenerSJBarrLABurchenalJERandomized, placebo-controlled trial of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade with primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. ReoPro and Primary PTCA Organization and Randomized Trial (RAPPORT) InvestigatorsCirculation19989887347419727542

- MontalescotGBarraganPWittenbergOPlatelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition with coronary stenting for acute myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med2001344251895190311419426

- NeumannFJKastratiASchmittCEffect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade with abciximab on clinical and angiographic restenosis rate after the placement of coronary stents following acute myocardial infarctionJ Am Coll Cardiol200035491592110732888

- Effects of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade with tirofiban on adverse cardiac events in patients with unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction undergoing coronary angioplasty. The RESTORE Investigators. Randomized Efficacy Study of Tirofiban for Outcomes and REstenosisCirculation1997965144514539315530

- van’t HofAWErnstNde BoerMJFacilitation of primary coronary angioplasty by early start of a glycoprotein 2b/3a inhibitor: results of the ongoing tirofiban in myocardial infarction evaluation (On-TIME) trialEur Heart J2004251083784615140531

- Van’t HofAWTen BergJHeestermansTPrehospital initiation of tirofiban in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty (On-TIME 2): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trialLancet2008372963853754618707985

- Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of eptifibatide on complications of percutaneous coronary intervention: IMPACT-II. Integrilin to Minimise Platelet Aggregation and Coronary Thrombosis-IILancet19973499063142214289164315

- Novel dosing regimen of eptifibatide in planned coronary stent implantation (ESPRIT): a randomised, placebo-controlled trialLancet200035692472037204411145489

- HorwitzPABerlinJASauerWHLaskeyWKKroneRJKimmelSEBleeding risk of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists in broad-based practice (results from the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions Registry)Am J Cardiol200391780380612667564

- BoersmaEHarringtonRAMoliternoDJPlatelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of all major randomised clinical trialsLancet2002359930218919811812552

- TopolEJMoliternoDJHerrmannHCComparison of two platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, tirofiban and abciximab, for the prevention of ischemic events with percutaneous coronary revascularizationN Engl J Med2001344251888189411419425

- ValgimigliMCampoGPercocoGComparison of angioplasty with infusion of tirofiban or abciximab and with implantation of sirolimus-eluting or uncoated stents for acute myocardial infarction: the MULTISTRATEGY randomized trialJAMA2008299151788179918375998

- De LucaGUcciGCassettiEMarinoPBenefits from small molecule administration as compared with abciximab among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: a meta-analysisJ Am Coll Cardiol200953181668167319406342

- KastratiAMehilliJNeumannFJAbciximab in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel pretreatment: the ISAR-REACT 2 randomized trialJAMA2006295131531153816533938

- RasoulSOttervangerJPde BoerMJA comparison of dual vs triple antiplatelet therapy in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results of the ELISA-2 trialEur Heart J200627121401140716682384

- GiuglianoRPWhiteJABodeCEarly versus delayed, provisional eptifibatide in acute coronary syndromesN Engl J Med2009360212176219019332455

- MehilliJKastratiASchulzSAbciximab in patients with acute ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel loading: a randomized double-blind trialCirculation2009119141933194019332467

- FungAYSawJStarovoytovAAbbreviated infusion of eptifibatide after successful coronary intervention The BRIEF-PCI (Brief Infusion of Eptifibatide Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) randomized trialJ Am Coll Cardiol2009531083784519264239

- BertrandOFDe LarochelliereRRodes-CabauJA randomized study comparing same-day home discharge and abciximab bolus only to overnight hospitalization and abciximab bolus and infusion after transradial coronary stent implantationCirculation2006114242636264317145988

- MarmurJDMitreCABarnathanECavusogluEBenefit of bolus-only platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition during percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the very early outcomes in the Evaluation of 7E3 for the Prevention of Ischemic Complications (EPIC) trialAm Heart J2006152587688117070148

- MarmurJDPoludasuSAgarwalAManjappaNCavusogluEHigh-dose tirofiban administered as bolus-only during percutaneous coronary interventionJ Invasive Cardiol2008202535818252967

- MarmurJDPoludasuSAgarwalABolus-only platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibition during percutaneous coronary interventionJ Invasive Cardiol2006181152152617090813

- MarmurJDPoludasuSLazarJCavusogluELong-term mortality after bolus-only administration of abciximab, eptifibatide, or tirofiban during percutaneous coronary interventionCatheter Cardiovasc Interv200973221422119156882

- TherouxPOuimetHMcCansJAspirin, heparin, or both to treat acute unstable anginaN Engl J Med198831917110511113050522

- OlerAWhooleyMAOlerJGradyDAdding heparin to aspirin reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction and death in patients with unstable angina. A meta-analysisJAMA1996276108118158769591

- CohenMDemersCGurfinkelEPA comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery disease. Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q-Wave Coronary Events Study GroupN Engl J Med199733774474529250846

- AntmanEMMcCabeCHGurfinkelEPEnoxaparin prevents death and cardiac ischemic events in unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Results of the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 11B trialCirculation1999100151593160110517729

- AntmanEMCohenMRadleyDAssessment of the treatment effect of enoxaparin for unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. TIMI 11B-ESSENCE meta-analysisCirculation1999100151602160810517730

- FergusonJJCaliffRMAntmanEMEnoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes managed with an intended early invasive strategy: primary results of the SYNERGY randomized trialJAMA20042921455415238590

- de LemosJABlazingMAWiviottSDEnoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in patients treated with tirofiban, aspirin and an early conservative initial management strategy: results from the A phase of the A-to-Z trialEur Heart J200425191688169415451146

- EikelboomJWAnandSSMalmbergKWeitzJIGinsbergJSYusufSUnfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin in acute coronary syndrome without ST elevation: a meta-analysisLancet200035592191936194210859038

- PetersenJLMahaffeyKWHasselbladVEfficacy and bleeding complications among patients randomized to enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin for antithrombin therapy in non-ST-Segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a systematic overviewJAMA20042921899615238596

- BassandJPHammCWArdissinoDGuidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromesEur Heart J200728131598166017569677

- ColletJPMontalescotGLisonLPercutaneous coronary intervention after subcutaneous enoxaparin pretreatment in patients with unstable angina pectorisCirculation2001103565866311156876

- DenardoSJDavisKETchengJEEffectiveness and safety of reduced-dose enoxaparin in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome followed by antiplatelet therapy alone for percutaneous coronary interventionAm J Cardiol200710091376138217950793

- ClarkNPLow-molecular-weight heparin use in the obese, elderly, and in renal insufficiencyThromb Res2008123Suppl 1S58S6118809206

- LimWDentaliFEikelboomJWCrowtherMAMeta-analysis: low-molecular-weight heparin and bleeding in patients with severe renal insufficiencyAnn Intern Med2006144967368416670137

- NutescuEASpinlerSAWittkowskyADagerWELow-molecular-weight heparins in renal impairment and obesity: available evidence and clinical practice recommendations across medical and surgical settingsAnn Pharmacother20094361064108319458109

- AntmanEMHandMArmstrongPW2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice GuidelinesJ Am Coll Cardiol200851221024718191746

- BittlJAStronyJBrinkerJATreatment with bivalirudin (Hirulog) as compared with heparin during coronary angioplasty for unstable or postinfarction angina. Hirulog Angioplasty Study InvestigatorsN Engl J Med1995333127647697643883

- LincoffAMKleimanNSKottke-MarchantKBivalirudin with planned or provisional abciximab versus low-dose heparin and abciximab during percutaneous coronary revascularization: results of the Comparison of Abciximab Complications with Hirulog for Ischemic Events Trial (CACHET)Am Heart J2002143584785312040347

- GibsonCMMorrowDAMurphySAA randomized trial to evaluate the relative protection against post-percutaneous coronary intervention microvascular dysfunction, ischemia, and inflammation among antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents: the PROTECT-TIMI-30 trialJ Am Coll Cardiol200647122364237316781360

- StoneGWMcLaurinBTCoxDABivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromesN Engl J Med2006355212203221617124018

- WhiteHDOhmanEMLincoffAMSafety and efficacy of bivalirudin with and without glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention 1-year results from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY) trialJ Am Coll Cardiol2008521080781418755342

- WhiteHDChewDPHoekstraJWSafety and efficacy of switching from either unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin to bivalirudin in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes managed with an invasive strategy: results from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY) trialJ Am Coll Cardiol200851181734174118452778

- StoneGWWitzenbichlerBGuagliumiGBivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med2008358212218223018499566

- LincoffAMSteinhublSRManoukianSVInfluence of Timing of Clopidogrel Treatment on the Efficacy and Safety of Bivalirudin in Patients With Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention An Analysis of the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY) TrialJACC Cardiovasc Interv20081663964819463378

- KastratiANeumannFJMehilliJBivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin during percutaneous coronary interventionN Engl J Med2008359768869618703471

- LincoffAMBittlJAHarringtonRABivalirudin and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade compared with heparin and planned glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade during percutaneous coronary intervention: REPLACE-2 randomized trialJAMA2003289785386312588269

- HillisLDLangeRAOptimal management of acute coronary syndromesN Engl J Med2009360212237224019458369

- AntmanEMCohenMBerninkPJThe TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision makingJAMA2000284783584210938172

- EagleKALimMJDabbousOHA validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registryJAMA2004291222727273315187054

- BoersmaEPieperKSSteyerbergEWPredictors of outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST-segment elevation. Results from an international trial of 9461 patients. The PURSUIT InvestigatorsCirculation2000101222557256710840005

- SubherwalSBachRGChenAYBaseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) Bleeding ScoreCirculation2009119141873188219332461

- LopesRDAlexanderKPManoukianSVAdvanced age, anti-thrombotic strategy, and bleeding in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) trialJ Am Coll Cardiol200953121021103019298914

- DiezJGCohenMBalancing myocardial ischemic and bleeding risks in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctionAm J Cardiol2009103101396140219427435

- ZikriaJCAnsellJOral anticoagulation with factor Xa and thrombin inhibitors: on the threshold of changeCurr Opin Hematol2009

- MegaJLBraunwaldEMohanaveluSRivaroxaban versus placebo in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ATLAS ACS-TIMI 46): a randomised, double-blind, phase II trialLancet20093749683293819539361

- AlexanderJHBeckerRCBhattDLApixaban, an oral, direct, selective factor Xa inhibitor, in combination with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: results of the Apixaban for Prevention of Acute Ischemic and Safety Events (APPRAISE) trialCirculation2009119222877288519470889

- SteffelJLuscherTFNovel anticoagulants in clinical development: focus on factor Xa and direct thrombin inhibitorsJ Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown)200910861662319561526