Abstract

The US FDA has encouraged the development of abuse-deterrent formulations (ADFs) of opioid analgesics as one component in a comprehensive effort to combat prescription opioid abuse. Guidance issued by the FDA outlines three types of premarket studies for evaluating abuse deterrence: laboratory-based in vitro manipulation and extraction studies, pharmacokinetic studies and human abuse potential studies. After approval, postmarket studies are needed to evaluate the impact of an ADF product on abuse in real-world settings. This review summarizes the regulatory issues involved in the development of ADF opioids and clarifies abuse-deterrence claims in product labels, in order to assist clinicians in critically evaluating the available evidence pertaining to the abuse-deterrent features of opioid analgesics.

There is a need to balance benefits and risks in opioid prescribing to reduce prescription opioid misuse and abuse while preserving accessibility of opioid medications for patients with chronic pain.

Abuse-deterrent formulations (ADF) of opioid analgesics have properties that make it difficult to extract the active ingredient or make abuse of the manipulated product less rewarding or, in the case of extended-release (ER) opioids, make it difficult to defeat the ER properties.

The US FDA evaluates evidence from laboratory-based in vitro manipulation and extraction studies, pharmacokinetic studies and human abuse potential studies to determine whether claims of abuse deterrence are warranted for an opioid medication.

At this time, four opioids with FDA-approved abuse-deterrent labeling are on the market; all are ER products.

These ADF opioids vary with regard to available study data and the routes of administration for which they are expected to reduce or deter abuse.

Information about abuse-deterrent characteristics is summarized in a specific section of the product label.

Widespread prescribing of non-ADF opioids undercuts the protections afforded by newer ADF products; however, the higher cost of ADF opioids and associated limitations in payer coverage are relevant considerations in medication selection.

Background

The abuse of prescription opioid analgesics has escalated into a widely recognized public health crisis [Citation1,Citation2]. Despite the potential for abuse, however, opioid therapy may be important for patients for whom nonpharmacologic therapies and nonopioid medications do not provide adequate pain relief [Citation3,Citation4]. Thus, there is a need to balance risks and benefits in opioid prescribing [Citation4–6].

Prescription opioids are abused via multiple routes, including oral consumption of intact medications, oral ingestion after product manipulation (such as crushing or chewing), nasal inhalation (‘snorting’) and injection [Citation7,Citation8]. Manipulation for nonoral use, which occurs with both immediate-release and extended-release (ER) opioids, is intended to convert the active ingredient to a form that is more easily abused (e.g., powder for nasal inhalation, solution for intravenous (IV) injection ) and to release the opioid more rapidly (known as dose dumping) [Citation9–12]. More severe medical outcomes are observed with nonoral routes of opioid administration [Citation13]. In addition, abuse of prescription opioid medications by tampering is associated with greater medical costs than abuse without tampering [Citation14].

The development of abuse-deterrent formulations (ADFs) of opioid analgesics is one component of a multifaceted strategy for reducing opioid misuse and abuse while maintaining the availability of opioid medications for appropriate patients [Citation9,Citation15]. Abuse-deterrent opioids have properties (e.g., physical/chemical barriers, opioid agonist/antagonist combinations) that are intended to hinder manipulation or make abuse of the manipulated product less rewarding [Citation16]. The US FDA has actively encouraged the development of ADFs of opioid analgesics, with the stated goal of meaningfully deterring abuse, even though such products will not fully prevent abuse [Citation16,Citation17]. The aims of this review are to summarize the regulatory issues involved in the development of ADF opioids and to clarify abuse-deterrence claims. This information is intended to assist clinicians in critically evaluating the available evidence pertaining to the abuse-deterrent features of opioid analgesics.

Methodology

A PubMed search of the Medline database conducted in July 2019 using the search term ‘abuse-deterrent’ (in the title or abstract of journal articles) yielded 291 citations. For this narrative review, articles were selected for further consideration based on their relevance to the topic of interest and included studies on tamper resistance and human abuse potential, reviews of FDA-approved ADF opioids currently in clinical use, and articles describing FDA guidelines and regulatory issues surrounding the development of ADFs.

Criteria for defining an opioid as abuse-deterrent

Manufacturers that design opioid products with putative abuse-deterrent properties conduct research to demonstrate abuse deterrence; the FDA decides whether the evidence is sufficient to allow data from these studies to be included in product labels and for the companies to make claims of abuse deterrence [Citation16]. The FDA evaluation of evidence related to abuse deterrence is an additional determination beyond the standard efficacy and safety evaluations mandated for all products submitted for review.

ADF technologies

A variety of technologies have been identified by the FDA as mechanisms for abuse deterrence [Citation16]. Currently marketed abuse-deterrent opioids use physical and chemical barriers to resist drug release/extraction [Citation18–21]. ADFs containing both an opioid agonist and a sequestered opioid antagonist, which is released when the product is manipulated, were previously available but have been discontinued (most recently Embeda® in November 2019) [Citation22]. Other potential abuse-deterrent technologies include those that cause aversion (via components that produce an unpleasant effect if the product is manipulated), delivery systems that may be difficult to manipulate (e.g., depot injectable formulation or subcutaneous implant), and new molecular entities (e.g., compounds with different receptor-binding profiles, slower penetration into the central nervous system or other novel effects) and prodrugs (i.e., compounds that need in vivo enzymatic activation for conversion to the parent drug) [Citation16].

Research to evaluate abuse deterrence

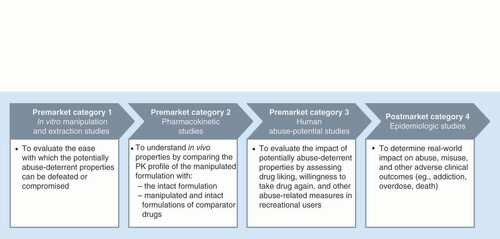

The FDA outlines four categories of research on abuse-deterrent opioid characteristics () [Citation16]. Submission of data from three types of premarket studies is required for evaluation of abuse deterrence: laboratory-based in vitro manipulation and extraction studies (category 1), pharmacokinetic (PK) studies (category 2) and human abuse potential studies (category 3). After approval, postmarket studies (category 4) are needed to evaluate the impact of an ADF product on abuse in real-world settings.

PK: Pharmacokinetic.

Each product is subjected to a large number of in vitro manipulation and extraction (category 1) studies that attempt to isolate the active pharmaceutical ingredient using a variety of household tools, solvents and extraction temperatures; ADF products also are evaluated using different comparators, doses, analysis time points and other variables [Citation23]. Physical manipulation studies consider the ability of the product to resist particle size reduction by crushing, cutting, grating or grinding with multiple tools [Citation10]. Chemical extraction studies investigate product characteristics that include the yield of opioid extracted, time required for extraction, solvents used (with greater concern for successful extraction with ingestible solvents), solvent volume required, conditions required for extraction (e.g., high temperature and continuous agitation) and resources required (e.g., advanced laboratory equipment) [Citation10]. In evaluating the potential for IV administration, syringeability and injectability of the extracted drug are key factors [Citation24].

PK (category 2) studies evaluate whether manipulation of the ADF product alters the PK profile of the drug [Citation16]. In particular, results of these studies indicate whether deliberate manipulation by abusers or accidental misuse by patients (e.g., crushing tablets to make them easier to swallow) would increase the maximum plasma concentration of the drug (Cmax) or shorten the time to maximum plasma concentration (tmax), both of which are indicators of abuse potential [Citation25]. PK studies employ a traditional PK study design, such as a crossover trial, with data analyzed for bioequivalence [Citation16]. The PK profile of the manipulated ADF product is compared with that of the intact ADF product, and also is compared with manipulated and intact versions of a non-ADF comparator administered via one or more routes of administration (usually oral or intranasal) [Citation16]. The methods of manipulation used in PK studies are those identified as the most effective (i.e., resulting in the greatest drug release) during in vitro (category 1) studies [Citation16].

Human abuse potential (category 3) studies are conducted in recreational opioid users to evaluate the attractiveness of the ADF product (intact and manipulated) compared with a positive control (e.g., a non-ADF immediate-release opioid) and with placebo [Citation16,Citation26]. Typically, separate studies are conducted to evaluate abuse potential by different routes of administration (e.g., oral and intranasal) [Citation16]. Outcomes in abuse potential studies include subjective measures of drug liking, willingness to take the drug again, and other drug characteristics (e.g., high, good effects and bad effects), measured using 100-mm visual analog scales, as well as physiologic measures (e.g., pupil size) [Citation16,Citation26]. PK (category 2) data may also be collected during these studies [Citation26]. To support abuse-deterrent labeling, the peak effect (i.e., mean Emax score) on the scales for drug liking and willingness to take drug again must be significantly lower for the putative ADF opioid relative to the non-ADF comparator [Citation10]. Another consideration is whether a statistically significant difference between the ADF and non-ADF products is clinically meaningful with regard to abuse potential. Consensus on what constitutes a clinically meaningful difference is currently lacking, but studies have suggested that a between-drug difference of approximately 5–10 mm (or more) on the drug liking or drug high visual analog scales is clinically relevant [Citation27,Citation28].

Postmarket studies (category 4) are important for confirming that ADFs reduce prescription opioid abuse in real-world settings [Citation16]. Sources of data for such studies include the Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS®) system [Citation29], Inflexxion’s National Addictions Vigilance Intervention and Prevention Program (NAVIPPRO™) [Citation30], and health insurance claims databases (e.g., Optum®, Truven Health MarketScan®). However, conducting postmarket studies of ADF opioids is challenging for several reasons, including confounding factors (because multiple interventions to reduce opioid abuse have been introduced simultaneously) and the relatively small population of patients who have been prescribed newer ADF medications [Citation31,Citation32]. The FDA’s stated goal for postmarket studies is to demonstrate ‘meaningful reductions in abuse, misuse and related adverse clinical outcomes [Citation16].’ In 2017, the FDA endorsed a new two-phase approach in which the first phase includes descriptive, feasibility and safety surveillance data, and the second phase (which depends on sufficient market uptake) consists of hypothesis testing studies. In addition to epidemiologic and surveillance data, the FDA may require experimental data to support label claims based on postmarket (category 4) data [Citation10].

Identifying & interpreting information on abuse deterrence in product labels

Four ER opioids with FDA-approved abuse-deterrence label claims are currently available: hydrocodone (Hysingla® ER, Purdue Pharma L.P., SCT, USA), morphine (MorphaBond™ ER, Daiichi Sankyo, NJ, USA) and oxycodone (OxyContin® ER, Purdue Pharma; Xtampza® ER, Collegium Pharmaceutical, Inc, MA, USA). Only one IR opioid has been approved as abuse-deterrent: oxycodone immediate-release (RoxyBond™, Daiichi Sankyo) [Citation33] was approved in 2017 but is not commercially available as of this writing.

If results from category 1–3 studies are included in the prescribing information for an opioid medication, they can be found in section 9.2 (Abuse) under the heading ‘Abuse Deterrence Studies’. Subheadings include in vitro ‘Testing’ (category 1), ‘Pharmacokinetic Studies’ (category 2) and ‘Clinical Studies’ (category 3). Highlights of study results available for each ADF product are presented under the corresponding subheading. For PK (category 2) and clinical abuse potential (category 3) studies, results are presented separately for oral and intranasal administration. Abuse-deterrence claims are detailed in the ‘Summary’ paragraph at the end of section 9.2. The summary includes the routes of administration (i.e., oral, intranasal and IV) for which the ADF is expected to reduce or deter abuse. A product may have evidence supporting reduced abuse potential by some routes of administration but not others (e.g., reduced potential for intranasal but not for oral abuse).

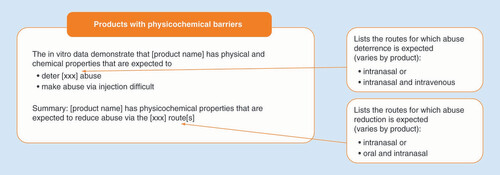

Specific language is used to describe abuse-deterrent properties in product labeling () [Citation18–21]. Conclusions from in vitro (category 1) studies state that the product has physical and chemical properties that are expected to ‘deter (intranasal and/or IV) abuse’ or ‘make abuse via injection difficult.’ The summary states that, based on the evidence, the product is ‘expected to reduce abuse via the (intranasal, oral and intranasal) route.’ For products that include study results in the label but do not have abuse-deterrence claims, the summary at the end of section 9.2 of the prescribing information includes a statement that there is “no evidence that (the product) has a reduced abuse liability compared with (the active comparator)” or a statement that study results “do not support a finding that (the product) can be expected to deter abuse.”

summarizes the abuse-deterrence claims from the prescribing information for commercially available abuse-deterrent opioids [Citation18–21,Citation34–50]. All abuse-deterrent opioid labels include a statement saying that abuse (by oral, intranasal and/or IV routes) is still possible. All abuse-deterrent opioid labels also include a statement that additional data, including epidemiologic data (i.e., from category 4 studies), when available, may provide further information on abuse liability. As of this writing, no ADF opioid labeling includes postmarket (category 4) data or claims.

Table 1. Abuse-deterrence claims in prescribing information for commercially available opioid analgesics.

Considerations in abuse-deterrent opioid prescribing

Responsible opioid prescribing requires clinicians to employ appropriate risk-management strategies without denying pain control to patients in need [Citation3,Citation5]. Abuse-deterrent opioids represent one component of a comprehensive plan that clinicians may employ to reduce opioid misuse, abuse and diversion [Citation51]. Other risk-reduction strategies for patients with chronic pain may include pretreatment risk assessment, use of prescription drug monitoring programs, urine drug testing, treatment of opioid addiction and psychiatric disorders, education programs for patients and prescribers, safe disposal programs and pain management in a multidisciplinary program [Citation1,Citation5,Citation51,Citation52]. Risk assessment should include not only the patient, but also the patient’s environment (e.g., substance abuse history of other household members and a plan for secure medication storage) [Citation53]. Abuse-deterrent opioids have the potential benefit of protecting people in the patient’s household and social circle by making opioid medications less attractive for diversion and subsequent abuse. The impact of abuse-deterrent opioids, and other individual components, should be evaluated in the context of an orchestrated, multifaceted approach for reducing the risks associated with opioid prescribing.

Widespread prescribing of non-ADF opioids undercuts the protections afforded by newer ADF products [Citation54,Citation55]. An FDA analysis of opioid prescription data from 2011 through 2016, calculated in morphine milligram equivalents, found that ADF products accounted for only 5–6% of opioid analgesics sold during that time frame [Citation56]. The higher cost of ADF opioids and associated limitations in payer coverage are important considerations and have contributed to the low uptake of ADF opioids observed thus far [Citation55]. Verification of the formulary placement of an ADF opioid in the patient’s insurance program is a necessary step when selecting an opioid medication.

Opioid therapy may be beneficial as part of a multimodal treatment program for chronic pain. Combination pharmacotherapy may be designed to target multiple pain mechanisms, although the safety and tolerability of specific medication combinations must, of course, be considered [Citation57]. Concurrent participation in nonpharmacologic interventions (e.g., physical therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy and acupuncture) may also help to optimize pain relief [Citation58].

Conclusion

Abuse-deterrent opioids represent a therapeutic option to maximize pain relief in patients for whom opioid analgesia is indicated, while reducing the risks of abuse and diversion. The FDA evaluates the results from in vitro manipulation and extraction (category 1), PK (category 2) and clinical human abuse potential (category 3) studies to determine whether the accumulated evidence is sufficient to warrant claims of abuse deterrence. Four ER opioids currently available in the USA were approved with abuse-deterrent labeling. However, these ADF opioids vary with regard to available study data (categories 1–3) and the routes of administration for which they are expected to reduce or deter abuse. The product labeling (section 9.2) summarizes the abuse-deterrent properties of an opioid medication. Postmarket (category 4) research evaluates the effects of ADFs on real-world abuse; however, such data are not currently included in any ADF opioid label.

Future perspective

As new, broadly efficacious, nonopioid analgesics are not expected in the near future, prescription opioids are currently necessary for the treatment of chronic pain in appropriate patients for whom nonopioid therapies are inadequate. ADF opioids provide an option for reducing the abuse or misuse of oral opioid products. Increased use of ADF opioids could protect not only the patient but also people in the patient’s environment from risks associated with opioid abuse and diversion. However, barriers (e.g., inadequate payer coverage) have limited the use of ADFs thus far. It remains to be seen whether there will be a shift in payer policy to allow coverage of comprehensive pain management care that includes ADF opioids. Moving forward, data collection on efficacy, risk/benefit analysis and cost–effectiveness of ADF opioids will be paramount to more widespread adoption of these agents. Results from postmarketing (category 4) studies for new ADF opioids will provide additional information about the protections afforded by these products. It is still unclear, however, which criteria the FDA will use for determining whether postmarketing data are sufficient for inclusion in the product label.

Acknowledgments

Although Collegium Pharmaceutical, Inc. was involved in the review of the manuscript, the author independently controlled the content of this manuscript, the ultimate interpretation and the decision to submit it for publication in Pain Management.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

A Carinci reports serving as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories and serving on the advisory board for Collegium Pharmaceutical, Inc. The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Technical editorial and medical writing assistance was provided by N Holland, Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, PA, USA, under the direction of the author. Funding for this support was provided by Collegium Pharmaceutical, Inc., MA, USA.

References

- Compton WM , BoyleM , WargoE. Prescription opioid abuse: problems and responses. Prev. Med.80, 5–9 (2015).

- Shipton EA , ShiptonEE , ShiptonAJ. A review of the opioid epidemic: what do we do about it?Pain Ther.7(1), 23–36 (2018).

- Pergolizzi JV Jr , RosenblattM , LeQuangJA. Three years down the road: the aftermath of the CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Adv. Ther.36(6), 1235–1240 (2019).

- Alford DP . Opioid prescribing for chronic pain – achieving the right balance through education. N. Engl. J. Med.374(4), 301–303 (2016).

- Passik SD . Issues in long-term opioid therapy: unmet needs, risks, and solutions. Mayo Clin. Proc.84(7), 593–601 (2009).

- Carinci AJ , MaoJ. Pain and opioid addiction: what is the connection?Curr. Pain Headache Rep.14(1), 17–21 (2010).

- Gasior M , BondM , MalamutR. Routes of abuse of prescription opioid analgesics: a review and assessment of the potential impact of abuse-deterrent formulations. Postgrad. Med.128(1), 85–96 (2016).

- Vietri J , JoshiAV , BarsdorfAI , MardekianJ. Prescription opioid abuse and tampering in the United States: results of a self-report survey. Pain Med.15(12), 2064–2074 (2014).

- Nalamachu SR , ShahB. Abuse of immediate-release opioids and current approaches to reduce misuse, abuse, and diversion. Postgrad. Med. doi:10.1080/00325481.2018.15025691–7 (2018) ( Epub ahead of print).

- Miller CJ , DartRC , KatzNP , WebsterLR. Insights and issues from FDA Advisory Committee meetings on abuse-deterrent opioids. J. Opioid Manag.13(6), 379–389 (2017).

- Cicero TJ , EllisMS , KasperZA. Relative preferences in the abuse of immediate-release versus extended-release opioids in a sample of treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.26(1), 56–62 (2017).

- Butler SF , BlackRA , CassidyTA , DaileyTM , BudmanSH. Abuse risks and routes of administration of different prescription opioid compounds and formulations. Harm. Reduct. J.8, 29 (2011).

- Green JL , BucherBartelson B , LeLait MCet al. Medical outcomes associated with prescription opioid abuse via oral and non-oral routes of administration. Drug Alcohol Depend.175, 140–145 (2017).

- Vietri J , MastersET , BarsdorfAI , MardekianJ. Cost of opioid medication abuse with and without tampering in the USA. Clinicoecon. Outcomes Res.10, 433–442 (2018).

- Passik SD , HeitHA , DeGeorgeM. Reality and responsibility revisited: stakeholder accountability in the effort to develop safer opioids. J. Opioid Manag.13(6), 391–396 (2017).

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration . Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Abuse-Deterrent Opioids – Evaluation and Labeling: Guidance for Industry.US Food and Drug Administration, MD, USA (2015). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm334743.pdf

- Califf RM , WoodcockJ , OstroffS. A proactive response to prescription opioid abuse. N. Engl. J. Med.374(15), 1480–1485 (2016).

- Hysingla™ ER (hydrocodone bitartrate) extended-release tablets, for oral use, CII, package insert . Purdue Pharma L.P, CT, USA (2018).

- MorphaBond™ ER (morphine sulfate) extended-release tablets, for oral use CII, package insert . Daiichi Sankyo, Inc, NJ, USA (2018).

- OxyContin® (oxycodone hydrochloride) extended-release tablets, for oral use, CII, package insert . Purdue Pharma L.P, CT, USA (2018).

- Xtampza® ER (oxycodone) extended-release capsules, for oral use, CII, package insert . Patheon Pharmaceuticals, OH, USA (2018).

- Embeda® (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride) extended-release capsules, for oral use, CII, package insert . Pfizer Inc, NY, USA (2018).

- Altomare C , KinzlerER , BuchhalterAR , ConeEJ , CostantinoA. Laboratory-based testing to evaluate abuse-deterrent formulations and satisfy the Food and Drug Administration’s recommendation for category 1 testing. J. Opioid Manag.13(6), 441–448 (2017).

- Xu X , GuptaA , Al-GhabeishM , CalderonSN , KhanMA. Risk based in vitro performance assessment of extended release abuse deterrent formulations. Int. J. Pharm.500(1–2), 255–267 (2016).

- Raffa RB , PergolizziJVJr. Opioid formulations designed to resist/deter abuse. Drugs70(13), 1657–1675 (2010).

- US Department of Health & Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration . Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Assessment of Abuse Potential of Drugs. Guidance for Industry.US Department of Health & Human Services, MD, USA (2017).

- Eaton TA , ComerSD , RevickiDAet al. Determining the clinically important difference in visual analog scale scores in abuse liability studies evaluating novel opioid formulations. Qual. Life Res.21(6), 975–981 (2012).

- White AG , LeCatesJ , BirnbaumHG , ChengW , RolandCL , MardekianJ. Positive subjective measures in abuse liability studies and real-world nonmedical use: potential impact of abuse-deterrent opioids on rates of nonmedical use and associated healthcare costs. J. Opioid Manag.11(3), 199–210 (2015).

- Cicero TJ , DartRC , InciardiJA , WoodyGE , SchnollS , MunozA. The development of a comprehensive risk-management program for prescription opioid analgesics: Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS). Pain Med.8(2), 157–170 (2007).

- Butler SF , BudmanSH , LicariAet al. National Addictions Vigilance Intervention and Prevention Program (NAVIPPRO): a real-time, product-specific, public health surveillance system for monitoring prescription drug abuse. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.17(12), 1142–1154 (2008).

- Dart RC , IwanickiJL , DasguptaN , CiceroTJ , SchnollSH. Do abuse deterrent opioid formulations work?J. Opioid Manag.13(6), 365–378 (2017).

- Roland CL , SetnikB , BrownDA. Assessing the impact of abuse-deterrent opioids (ADOs): identifying epidemiologic factors related to new entrants with low population exposure. Postgrad. Med129(1), 12–21 (2017).

- RoxyBondTM (oxycodone hydrochloride) tablets, for oral use, CII, package insert . Daiichi Sankyo, Inc, NJ, USA (2018).

- Harris SC , CiprianoA , ColucciSVet al. Intranasal abuse potential, pharmacokinetics, and safety of once-daily, single-entity, extended-release hydrocodone (HYD) in recreational opioid users. Pain Med.17(5), 820–831 (2016).

- Harris SC , CiprianoA , ColucciSVet al. Oral abuse potential, pharmacokinetics, and safety of once-daily, single-entity, extended-release hydrocodone (HYD) in recreational opioid users. Pain Med.18(7), 1278–1291 (2017).

- DiFalco R , KinzlerER , PantaleonC , AignerS. Abuse-resistant, extended-release morphine is resistant to physical manipulation techniques commonly used by opioid abusers. Presented at: PAINWeek 2014.NV, USA, 2–6 September 2014.

- Bianchi R , KinzlerE , DiFalcoR , ShahM , AignerS. Extraction testing of a novel extended-release, abuse-deterrent formulation of morphine, morphine ARER, in common household solvents. J. Pain15(Suppl. 4), S77 (2014).

- Kinzler ER , PantaleonC , IversonMS , AignerS. Syringeability of morphine ARER, a novel, abuse-deterrent, extended-release morphine formulation. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse45(4), 377–384 (2019).

- Webster LR , PantaleonC , ShahMSet al. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, intranasal drug liking study on a novel abuse-deterrent formulation of morphine–morphine ARER. Pain Med.18(7), 1303–1313 (2017).

- Webster LR , PantaleonC , IversonM , SmithMD , KinzlerER , AignerS. Intranasal pharmacokinetics of morphine ARER, a novel abuse-deterrent formulation: results from a randomized, double-blind, four-way crossover study in nondependent, opioid-experienced subjects. Pain Res. Manag.2018, 7276021 (2018).

- Perrino PJ , ColucciSV , ApseloffG , HarrisSC. Pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and safety of intranasal administration of reformulated OxyContin® tablets compared with original OxyContin® tablets in healthy adults. Clin. Drug Investig.33(6), 441–449 (2013).

- Harris SC , PerrinoPJ , SmithIet al. Abuse potential, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of intranasally administered crushed oxycodone HCl abuse-deterrent controlled-release tablets in recreational opioid users. J. Clin. Pharmacol.54(4), 468–477 (2014).

- Kopecky EA , FlemingAB , NoonanPKet al. Impact of physical manipulation on in vitro and in vivo release profiles of Oxycodone DETERx®: an extended-release, abuse-deterrent formulation. J. Opioid Manag.10(4), 233–246 (2014).

- Gudin J , Levy-CoopermanN , KopeckyEA , FlemingAB. Comparing the effect of tampering on the oral pharmacokinetic profiles of two extended-release oxycodone formulations with abuse-deterrent properties. Pain Med.16(11), 2142–2151 (2015).

- Fleming AB , ScungioTA , GrimaMP , MayockSP. In vitro assessment of the potential for abuse via the intravenous route of oxycodone DETERx® microspheres. J. Opioid Manag.12(1), 57–65 (2016).

- Brennan MJ , KopeckyEA , MarseillesA , O’ConnorM , FlemingAB. The comparative pharmacokinetics of physical manipulation by crushing of Xtampza® ER compared with OxyContin®. Pain Manag.7(6), 461–472 (2017).

- Mayock SP , SaimS , FlemingAB. In vitro drug release after crushing: evaluation of Xtampza® ER and other ER opioid formulations. Clin. Drug Investig.37(12), 1117–1124 (2017).

- Webster LR , KopeckyEA , SmithMD , FlemingAB. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study to evaluate the intranasal human abuse potential and pharmacokinetics of a novel extended-release abuse-deterrent formulation of oxycodone. Pain Med.17(6), 1112–1130 (2016).

- Kopecky EA , FlemingAB , Levy-CoopermanN , O’ConnorM , SellersEM. Oral human abuse potential of oxycodone DETERx® (Xtampza® ER). J. Clin. Pharmacol.57(4), 500–512 (2017).

- Meske D , KopeckyEA , PassikS , ShramMJ. Evaluation of the oral human abuse potential of oxycodone DETERx® formulation (Xtampza® ER). J. Opioid Manag.14(5), 359–372 (2018).

- Passik SD , NarayanaA , YangR. Aberrant drug-related behavior observed during a 12-week open-label extension period of a study involving patients taking chronic opioid therapy for persistent pain and fentanyl buccal tablet or traditional short-acting opioid for breakthrough pain. Pain Med.15(8), 1365–1372 (2014).

- Jamison RN , SerraillierJ , MichnaE. Assessment and treatment of abuse risk in opioid prescribing for chronic pain. Pain Res. Treat.2011, 941808 (2011).

- Adler JA , Mallick-SearleT. An overview of abuse-deterrent opioids and recommendations for practical patient care. J. Multidiscip. Healthc.11, 323–332 (2018).

- Rauck RL . Mitigation of IV abuse through the use of abuse-deterrent opioid formulations: an overview of current technologies. Pain Practice19(4), 443–454 (2019).

- Cohen JP , MendozaM , RolandC. Challenges involved in the development and delivery of abuse-deterrent formulations of opioid analgesics. Clin. Ther.40(2), 334–344 (2018).

- US Food & Drug Administration . FDA analysis of long-term trends in prescription opioid analgesic products: quantity, sales, and price trends (2018). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/UCM598899.pdf

- Dale R , StaceyB. Multimodal treatment of chronic pain. Med. Clin. North Am.100(1), 55–64 (2016).

- Tompkins DA , HobelmannJG , ComptonP. Providing chronic pain management in the “fifth vital sign” era: historical and treatment perspectives on a modern-day medical dilemma. Drug Alcohol Depend.173(Suppl. 1), S11–S21 (2017).