ABSTRACT

Conclusions En bloc resection should always be primarily considered in ear carcinoma, also in advanced tumors growing beyond the walls of the external auditory canal, because it achieves a full specimen for histopathological evaluation and allows a correlation between clinical, pathological features, and outcomes. Objective and methods Dismal outcome of surgical and radiotherapic therapies for advanced ear carcinoma required a critical discussion of the oncological principles of treatment. Our analysis involved preliminarily a detailed description of surgical technique including the contribution of modern skull base microsurgery. Results Evident limits in diagnostic protocols, surgical treatment and outcome evaluation modalities pointed to the need of a new approach towards an accurate definition of pre-operative tumor location, size, and behavior. En bloc resection achieved a specimen for a final pathological evaluation and an adjunctive piecemeal excision was necessary only whenever resection was not felt falling in safe, tumor-free tissue. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be considered in selected cases for adjuvant treatment.

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the external auditory canal is an uncommon, locally aggressive malignancy, and radical surgical excision is considered the first choice for its treatment [Citation1]. Complete excision with free margins on final pathological examination is the main aim of temporal bone oncological surgery, and the literature generally judges positive margins a negative prognostic factor [Citation2]. The complexity of the temporal bone anatomy and the rarity of the disease (even at tertiary centers) have made it difficult to develop appropriate surgical techniques. Advanced cases extending beyond the boundaries of the external auditory canal have a dismal prognosis, even after extensive surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy.

As concerns appropriate surgical approaches, after the reports from Parson and Lewis [Citation3], Conley and Novack [Citation4], and Lewis [Citation5], clinical research has focused mainly on two options: en bloc or piecemeal resection. The latter removes the tumor bit by bit up until normal tissue is encountered, whereas en bloc resections follow an anatomical plane of dissection through normal tissue. A compromise between the two techniques is often adopted: the auditory canal is resected en bloc and the remaining tumor is then removed piecemeal. The main techniques have been described only briefly, making it quite difficult to discuss outcomes in relation to the surgical approach adopted.

Several authors [Citation6–9] have used piecemeal removal as their standard approach because of the technical difficulties of en bloc procedures. This in itself may be good reason to re-open the debate on the modern and rational principles of en bloc resection for temporal bone carcinoma, focusing in particular on surgical technique.

En bloc lateral temporal bone resection (LTBR)

The en bloc LTBR includes removal of the cartilaginous and bony external auditory canal with the ear drum, periauricular soft tissues, parotid (with or without the facial nerve), and neck lymph-nodes. Other structures may be sacrificed too, such as the condyle and part of the mandible. The procedure may involve resecting the neck, parotid, and temporal bone.

In both therapeutic and prophylactic neck dissections, the procedure follows well-established surgical steps. The neck lymph node levels removed necessarily varies depending on the clinical status of the neck. We recommend removing levels II–IV in cN0 cases; and levels I and V have to be considered too in pN + patients [Citation10]. The neck dissection has to run along the jugulo-carotid axis, following the internal carotid artery up to where it enters the skull base. The neck dissection includes the soft tissues of the infra-sphenotemporal fossa and remains continuous with the parotid gland.

As for the ear, the procedure begins with a wide C-shaped incision posterior to the retro-auricular sulcus, and the pinna may or may not be sacrificed, depending on its involvement. The incision continues inferiorly to the angle of the mandible, reaching the mid-third of the neck and beyond, as necessary for the planned neck dissection. The external auditory canal is cut where it meets the concha; the skin flap is turned anteriorly to reveal the parotid gland up to the masseter muscle. Inferiorly, the platysma is lifted to expose the neck fascial plane.

A retrograde parotidectomy is performed in cT1–T2 cases, identifying the facial nerve’s peripheral branches because searching for the nerve at its exit at the stylomastoid foramen can disrupt tissues potentially invaded by tumor. The handling of the facial nerve differs depending on the cT stage of the tumor.

LTBR technique in cT1–T2 cases

Once the skin flap has been raised, a circular incision is made on the fibro-periosteal plane all around the canal opening, and a second straight incision running posteriorly from the middle of the previous incision is used to obtain two flaps (one is raised cranially, the other caudally) to expose the mastoid, temporal, and occipital squamae.

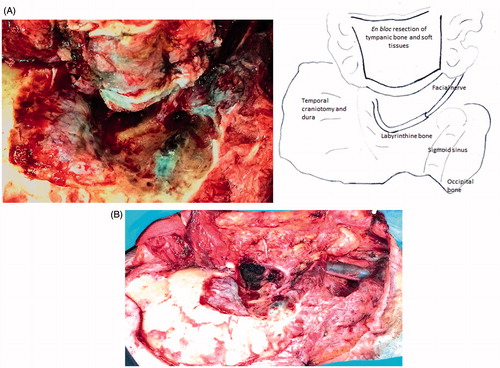

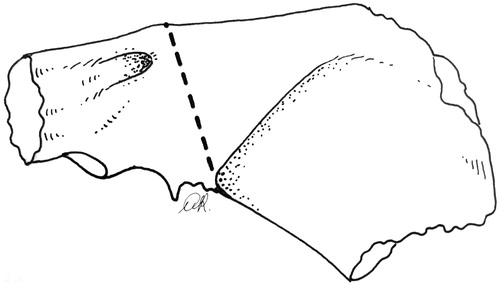

Work on the bone begins with a wide mastoidectomy, skeletonizing the middle fossa dura and sigmoid sinus (). Drilling exposes the soft tissue of the Fallopian canal along the posterior and lateral edges. The nerve is freed and drawn away from the osseous wall and from the fibrous tissue of the stylo-mastoid foramen, and followed into the parotid. The external auditory canal is not entered and its bony walls are freed en bloc from the surrounding planes by means of the following steps. Through an atticotomy, drilling on the anterior wall of the attic makes a groove up to the soft pre-auricular tissue, thus freeing the superior wall from the squamous bone. Drilling on the residual Fallopian canal proceeds up to the hypo-tympanum just laterally to the jugular bulb, thus freeing the posterior and medial aspects of the tympanic bone. Prolonged drilling on the inferior side of the tympanic bone is needed to reach the bony anterior aspect of the tympanic bone and the pre-auricular tissues. Small bony bridges are then disrupted to release the resection block, along with the dissected parotid gland and neck. In selected cT1 cases, resection of the canal can be done laterally to the mastoid portion of the facial nerve without freeing the full length of the nerve in the mastoid. If the bone between the canal roof and the dura is narrow, a craniotomy () may accommodate the osteotomy, freeing the cranial side of the canal (see the LTBR in cT3–T4 cases). At the end of the procedure, the specimen including the superficial parotid, neck dissection, and tympanic block is as shown in . The surgical field shows the facial nerve from tympanum to facial muscles.

LTBR in anterior cT3–T4 cases

Tumors originating on the anterior cartilaginous and/or bony wall without invading contiguous walls may penetrate through the bone and/or cartilage and grow inside the parotid space. These are T4 tumors according to the Pittsburgh classification [Citation11], while they have a lower grade according to our more recently proposed classification [Citation12]. They can be treated with a LTBR. The oncological margins of resection have to be wider than in T1–T2 cases, however, and go beyond the safety margins revealed by imaging. The medial limit of the resection is the internal carotid artery, which is cranio-caudally followed in the petrous bone up to its cervical tract. This approach avoids the need to expose the artery through a lateral trans-parotid route, violating the peritumoral tissues.

Skin incisions in the external auditory canal or in the concha auris, and in the periauricular soft tissues, are performed as in cT1–T2 cases, but with wider margins. The skin flap and fibro-periosteal flap are the same as those described previously for LTBR in cT1–T2 carcinomas.

Retrograde total parotidectomy starts from the anterior margin of the gland, where the facial nerve’s peripheral branches are cut and marked for subsequent grafting. Total parotidectomy extends posteriorly to include the styloid process, the facial nerve, and the infra-sphenotemporal fossa tissues. The continuity between the latter, the parotid gland, the anterior wall of the canal, and the neck dissection has to be preserved. A wide mastoidectomy is performed, exposing the middle and posterior fossa, dura mater, and sigmoid sinus.

The facial nerve is handled differently in LTBR for T3–T4 as opposed to T1–T2 tumors. The Fallopian canal is drilled to expose the nerve, which is cut in the middle of its mastoid tract. The distal branch is left with the resection block; the proximal branch is checked for tumor involvement on frozen section and then will receive a graft.

Specific cuts are performed in the bone to free the resection block as follows. An osteotomy is performed along the Fallopian canal as far as the hypo-tympanum between the jugular bulb and the tympanic annulus. Inferiorly, the incision follows the tympano-mastoid suture to behind the styloid process. The specimen is thus freed on its posterior aspect. The tympanic bone and temporal squama are still connected and have to be separated with a temporal osteotomy. A 4 × 4 cm temporal craniotomy is centered on the zygomatic root. The dura is separated from the petrous bone on the tegmen and up to the middle meningeal artery, oval foramen, and horizontal carotid artery. The arterial canal is drilled out to its genu and further along the vertical tract using a diamond burr with suction-irrigation. The anterior and lateral walls of the canal are removed as far as its cervical orifice (taking care to avoid damaging the cochlea). The artery is then separated from the other walls as it will be dislocated later on. The anterior osteotomy runs endo- and extra-cranially from the vertical carotid to the anterior aspect of the petrous bone up to the glenoid fossa; the zygomatic root will have been cut previously. The osteotomy ends at the inferior aspect of the skull base, between the carotid canal orifice and the sphenoid spine. The osteotomy is performed with the side-cutting Lindeman burr. The internal carotid artery has to be under constant visual control and can be dislocated as required during drilling. The block is freed by cutting on the tegmen tympani. Any residual bony bridges can be disrupted with an osteotome. The mandibular condyle resection is performed before the osteotomies are completed. The facial nerve graft is harvested from a donor nerve (sural or great auricular nerve) peripherally divided into two branches, or with two separate grafts and placed with 9/00 sutures.

On reconstruction, the external auditory canal is closed with a cul-de-sac suture on the residual skin of the canal or concha. The fibromuscular flaps are sutured. A rotational temporal flap can be used to fill the cavity. Excessive loss of substance can be replaced with a pedicled flap (trapezius or pectoralis major flap) or an occipital skin flap.

En bloc subtotal temporal bone resection (STBR) for non-anterior cT3–T4 carcinomas

Pre-operative digital angiography is indicated to check the patency of the torcular communication to allow for the sigmoid sinus-jugular vein to be closed. The possibility of an anterior cerebellar artery looping inside the internal acoustic meatus should also be ruled out by angio-MRI.

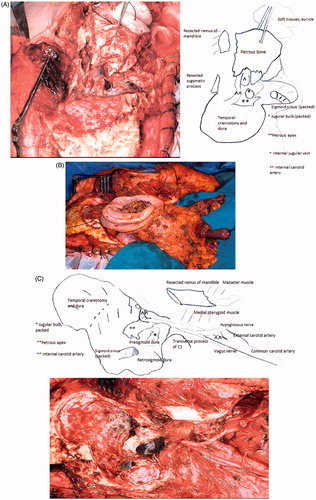

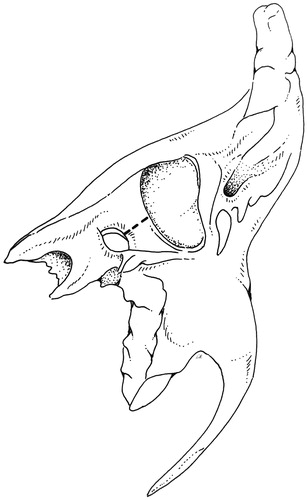

The STBR is an en bloc resection of the temporal bone except for its apical portion lying anteriorly to the internal auditory canal. The en bloc specimen includes the petrous bone, mastoid, bony and cartilaginous canal, the parotid gland with the facial nerve, part of the mandible (if necessary), and neck dissection. It basically involves a separation of the petro-tympanic bone from the dura, carotid, sigmoid sinus-jugular bulb and the lower cranial nerves, and lastly from the apex (). Temporal and occipital craniotomies enable both the separation and the osteotomies, which are conducted across the anterior, medial, and posterior aspects of the petrous bone. The carotid canal should be considered the focus of the resection, with the osteotomies departing from it towards the four (superior, posterior, inferior, lateral) sides of the temporal bone. The first two osteotomies are based on drilling to expose the large vessels, one on the sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb complex, the other on the horizontal and vertical carotid canal. The next four cuts start from the carotid canal, one to the jugular fossa, the next to the petrous ridge and thereon to the posterior side of the petrous bone down to the jugular fossa, the last to the glenoid. The periauricular tissues are left attached to the en bloc resection. At the end of the procedure (), the surgical field shows the medial boundary of the resection with the internal carotid artery from neck to petrous apex.

Figure 2. Right STBR in T4 tumor (surgical picture). (A) View from the vertex: the resected block of petrous bone is displaced inferiorly. The dura of the temporal and occipital craniotomies form the boundary of the approach. (B) Lateral view: neck dissection lies in continuity with the petrous bone block. (C) Lateral view: the surgical field after removal of the specimen. The internal carotid artery and petrous apex represent the medial boundary of resection.

A wide C-shaped skin incision across the temporal, occipital, and neck skin is needed to expose the surgical field properly. The flap is turned forward to the masseter muscle and downward to the neck. The external auditory canal is cut as described previously for LTBR, and the periauricular soft tissues are carefully inspected for metastatic nodules. A circumferential incision is performed around the canal orifice to include the perimeatal soft tissues in the resection block. A U-shaped inferiorly-rooted fibromuscular flap is turned on the cranio-cervical junction to complete the exposure of mastoid and occipital bone squama. The temporal squama is uncovered by raising a muscle flap of the posterior half of the temporal muscle rooted inferiorly on its tendon.

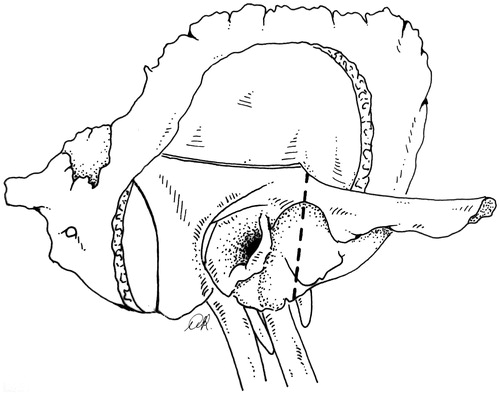

The bone work begins with a lateral occipital craniotomy () to expose the full sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb. The asterion is a landmark for this step as it lies ∼2 cm above the transverse to sigmoid junction and enables drilling there to find the sinuses without entering the mastoid. The drilling is done on the sigmoid surface and retrosigmoid dura without extending towards the mastoid. The pre-sigmoid petrous dura near the sinus is exposed for a few millimeters and separated from the petrous bone up to the border of the internal auditory meatus.

Figure 3. Right STBR. Lateral view: temporal and occipital craniotomies with exposure of the sigmoid-jugular bulb complex. The interrupted line indicates the lateral osteotomy.

The sigmoid sinus is opened and packed with Surgicel®, which is pushed upstream to the junction, and downstream into the jugular bulb. The jugular vein will have already been ligated on the neck. The sigmoid and bulb are opened and the petrosal and occipital affluents are closed with Surgicel®, taking care not to apply pressure on the medial wall of the bulb and damage the lower cranial nerves.

A temporal craniotomy, obtaining a flap 4 × 4 cm in size (), is centered on the zygomatic root. The dura is raised from the petrous surface up to the conventional landmarks (petrous ridge, middle meningeal artery, foramen ovale, and fibrous tissue on the horizontal carotid): the temporal and petrous dura thus become a single, compliant surface. The bone is drilled from the horizontal carotid canal up to the first knee, then down along the full length of the anterior and lateral surfaces of the vertical portion, and to the inferior orifice (). The artery is then freed from the other walls.

Figure 4. Right STBR. The superior side of the petrous bone as seen from the temporal craniotomy. Part of the horizontal and the full vertical carotid artery are exposed by drilling on the petrous bone surface. Two osteotomies (dashed line) depart from the vertical carotid canal. One osteotomy is directed posteriorly across the petrous surface up to the petrous ridge and cuts through the proximal third of the internal auditory canal. It will continue on the posterior side of the bone (). The second osteotomy runs across the anterior petrous surface to the glenoid fossa and thereon across the lateral side of the temporal bone ().

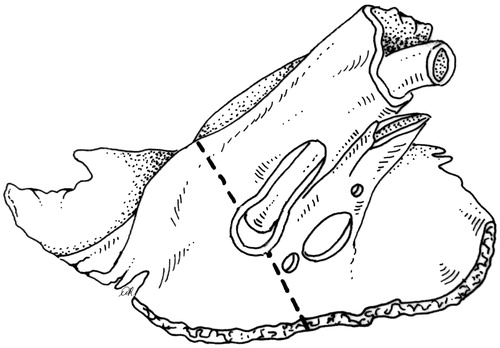

Going back to the occipital window, two cuts are done. The first is running from the petrous ridge down to the medial boundary of the jugular fossa (). The second is a groove drilled from the anterior aspect of the jugular fossa to the vertical carotid canal (). The artery has already been freed at the previous step, and can be safely displaced as necessary by drilling.

Figure 5. The posterior side of the petrous bone, as seen through the occipital craniotomy, shows the posterior osteotomy from the petrous ridge to the posterior boundary of the jugular fossa.

Figure 6. The inferior aspect of the temporal bone showing the orifice of the jugular vein and carotid artery. The inferior osteotomy (dashed line) is done from the occipital craniotomy and runs from the jugular fossa to the vertical carotid canal.

The next two osteotomies divide the pars petrosa of the temporal bone from the apex and the squama. The apical cut () runs from the carotid canal to the posterior petrous ridge, passing across the proximal third of the internal auditory canal, where the 7th and 8th nerves are severed by the advancing burr. An annular portion of the meatus is left attached to the petrous dura and sealed with bone wax. Pre-operative imaging is mandatory to show whether the anterior–inferior cerebellar artery loops inside the canal. Before cutting, the latter should then be opened and the artery displaced in the cerebello-pontine angle. If the medial osteotomy runs across the labyrinth and lateral to the acoustic meatus, the free margin may be lost on the infra-labyrinthine bone.

At this point, the petrous block is held by the squamous bone of the middle cranial fossa and the glenoid. The cut is conveniently done with a Lindeman-type side cutting burr. While holding the displaced carotid with the suction tube, the cut runs from the carotid canal across the middle cranial fossa floor to the glenoid fossa (), and from there to the orifice of the carotid canal (). The block is freed from any residual bone bridges using an elevator with a levering action and is carefully dislocated in the inferior–anterior direction. The soft tissues of fasciae, tendons, and muscle holding the bone block are cut from the petrous bone, one after the other, preferably at their furthermost point of attachment. The mandibular condyle or ramus can be severed without any loss of continuity with the specimen.

Even when all the tissues lateral to the cervico-petrous carotid are removed, recurrences can occur and pose the challenge of widening the boundaries of the operation. Piecemeal removal of the remaining bone, removal of the medial jugular wall along with the soft tissues in the area of transition from neck to skull can be considered. Sacrificing the carotid and/or lower cranial nerves, or total temporal bone resection, seem to be of no benefit [Citation13].

A tumor growing on the dura can be approached separately by resecting the dura at least 2 cm around the growth and repairing it with autologous fascia. Invaded portions of brain can be removed. CSF leaks are prevented by suturing dura tears and waxing the acoustic porus. The Eustachian tube is closed with a muscle plug, or by suturing the cartilaginous portion.

Reconstruction techniques depend on the amount of tissue loss. After replacing the bone flaps, temporal and mastoid muscle flaps can be turned and sutured to fill the cavity. If tissue loss is severe, then a pedicled or microvascular flap can be used.

Discussion

The en bloc resection of temporal bone entails a combination of well-known surgical steps and certainly demands a surgeon skilled in skull base and neck surgery, as well as a good knowledge of head and neck oncological principles.

Results from different centers converge on a different prognosis relating to early- and advanced-stage tumors. Growths remaining within the boundaries of the external auditory canal are amenable to successful surgery in the majority of cases by a LTBR, while the outcome remains poor for tumors advancing beyond the canal’s borders. The complicated anatomy and restricted margins of tumor-free tissue make safe removal difficult, so a critical discussion of the rationale for surgery in T3–T4 tumors is warranted. The two options, en bloc and piecemeal resection, each have their pros and cons.

The aim of en bloc resection in both LTBR and STBR is to remove a block of tissues enclosing the tumor along tumor-free planes. For this purpose, the tumor’s extent and the surgical planes of resection have to be identified precisely and carefully followed. The resulting surgical specimen then allows for final histopathological examination to establish the tumor’s extent and pT staging, and to confirm the oncological status of the surgical margins. The drawback of this approach is self-evident, since the amount of bone around the tumor has to be large enough to include a tumor-free layer and more bone has to be removed to enable the surgical maneuvers. The radicality of such a resection therefore depends on the site and extent of the tumor.

Piecemeal resection is performed more often than en bloc resection in advanced tumors, either alone [Citation6,Citation14] or as an adjunct to LTBR. Descriptions in the literature are meager. Dean et al. [Citation7, p. 1517] wrote, ‘A subtotal temporal bone resection was performed consisting of a lateral temporal bone resection and local excision of the involved portion of temporal bone’; and ‘… the tumor was removed en bloc, followed by aggressive skull base dissection consisting of drilling through tumor-involved skull base with methodical re-excision until negative margins were achieved…’. They also said that, ‘… piecemeal resection when aggressive and done in a sequential manner appears to be more effective than traditional en bloc skull base resection’. The same viewpoint was reported by Gidley et al. [Citation9], and by Prasad et al. [Citation8, p. 158], who stated that ‘… after LTBR, the procedure extends medially in a piecemeal fashion … adequate bone is removed around the tumor …’. This technique demands a subjective judgment of the removal achieved on free/negative margins, and cannot rely on any intra- or post-operative histopathological check on the free margins of bone. Most experienced authors support piecemeal resection and report results not inferior to en bloc resection, but the debate seems to be far from conclusive.

Our experience [Citation12,Citation15,Citation16] with en bloc resection achieved different oncological results depending on the site of primary tumor. Tumors extending from the anterior wall to the parotid space treated with LTBR + RT had a more favorable outcome than tumors growing from the other walls into mastoid and petrous bone, and treated with STBR + RT. The cases of anterior T4 carcinoma treated with parotidectomy and sacrificing the facial nerve had a favorable outcome, while patients whose facial nerve was preserved experienced local recurrence. LTBR in anterior T4 cancers seems to have a clear rationale in terms of tumor extent/resection and results, but this impression ought to be supported by larger series. It is difficult to compare data in the literature because authors have generally pooled T3 and T4 together, with the exception of Clark et al. [Citation17], who reported a better prognosis for anterior tumor.

T3 and T4 tumors are currently treated with en bloc LTBR, or with STBR resulting from en bloc LTBR and additional piecemeal resection to achieve ‘free/negative margins’ based on imaging and the surgeon’s judgment. The DFS ranges between 19–50%, with a follow-up that is sometimes less than 5 years. Results obtained with non-anterior tumors treated with STBR are decidedly poor due to local carcinoma recurrence [Citation16].

The persistently poor prognosis after combined surgery and radiation treatment for advanced tumors makes it necessary to critically review their current management. In our opinion, the crucial issues will emerge on correlating tumor/surgery/results. Information on tumor site and local extent is obtained on imaging, often with macroscopic errors of judgment. The size and site of a tumor and its relationship with the bone structure, the Fallopian canal, and other neurovascular structures are important because they influence the tumor’s diffusion. Pathological grading is not done for T staging purposes, although it affects the prognosis [Citation15]. The choice of which type of surgery is controversial too. En bloc resection may be a standardized procedure, but it requires a highly skillful hand and no deviations or compromises, and sufficient oncological-surgical space may not be available in a number of cases. The efficacy of piecemeal resection depends largely on the often poor detail of available imaging, and on the surgeon’s intraoperative judgment; it also does not allow for any pT staging.

An early diagnosis of recurrences is often lacking and, with it, the chance to identify the site of incomplete resection. An inaccurate assessment of a tumor’s extent, an apparent inconsistency between the evidence of free margins, and the carcinoma recurrence rate [Citation12] are different aspects of the same problem, which affect every surgical approach.

The current lack of progress in the treatment of advanced ear cancers means that the above-mentioned deficiencies in diagnosis, surgery, and evaluation of results need to be faced [Citation18]. The pre-operative assessment of such tumor characteristics as site and size (using cone-beam CT [Citation19] and targeted MRI on critical areas), grade, and prognostic factors such as node metastases and biological markers has a fundamental role. The extent of standardized en bloc surgery should be dictated by a plane of resection matching the oncological situation and the surgical space available. En bloc surgery enables pT classification and a correlation between pT classification, surgical procedure, and outcome. The role of piecemeal surgery is not secondary, however, since it is easier to achieve and may be the only solution when en bloc resection is not feasible and/or judged to be incomplete. A rational follow-up plan could provide more information, if MRI were repeated every 2 months in the first and second post-operative years, every 3 months in the third, and every 6 months in the fourth and fifth years. Treatments such as chemotherapy [Citation20] and targeted therapy with biological markers should be considered as part of the treatment process.

A comprehensive view based on the above-mentioned principles is given in , showing the procedure by class of tumor. En bloc resection should be the rule for any class of tumor. In non-anterior T4 cancers, en bloc resection provides a specimen for histopathological assessment; piecemeal resection could be useful for dealing with areas potentially beyond the reach of spatially-limited en bloc resections. Superficial parotidectomy has to be associated with surgery for early-stage tumors, while total parotidectomy including the facial nerve is for advanced-stage disease. Facial nerve grafting should be done when a proximal stump is available.

Table 1. T stage and surgical procedures.

Conclusions

This critical examination of en bloc resection for SCC of the ear first looks into the details of the surgical technique because this has never been done in the scientific journals or books on surgical procedures. Our step-by-step description is up-to-date and enriched with the surgical principles of skull base microsurgery.

Having described the surgical technique in detail and established the relevant surgical principles, the indications for surgery, outcome, and prognosis are discussed. It is common knowledge that en bloc LTBR achieves good results when tumors are confined within the boundaries of the external auditory canal with limited bone erosion (T1–T2). The same cannot be said of advanced tumors extending beyond the walls of the external auditory canal and spreading into the temporal bone or adjacent soft tissues.

There are differences in the prognosis for tumors of advanced stage according to some authors. When tumors originate from the anterior wall of the external auditory canal and spread into the parotid space, en bloc LTBR with total parotidectomy and facial nerve sacrifice affords a better prognosis than in other advanced-stage tumors. T3–T4 tumors growing from the canal into the mastoid or petrous bone have a dismal prognosis, even if they are treated with STBR followed by RT. This raises the question of whether a critical analysis of these tumors’ management might reveal an erroneous treatment approach and point to a more appropriate type of surgery. An accurate pre-operative classification of tumors using modern imaging techniques, standard surgical indications, and a standardized use of en bloc resections should become the rule. It is within this frame that the pathologist can assess a tumor’s pT class and enable a correlation between pre-operative findings (clinical-radiological staging), type of surgery, results, and the site of any recurrences.

The ultimate goal of standardized procedures with histopathology of the surgical specimen (which has already played an important part in other tumors) is to achieve a shared treatment. This is the only way to study cohorts of patients with statistical methods and enable meaningful comparisons of results.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Anna Rambaldo, Institute of Human Anatomy, Department of Molecular Medicine, University of Padova, for her anatomical drawings of the temporal bone; they also thank Frances Coburn for correcting the English version of this paper.

Declaration of interest

the authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Moffat DA, Wagstaff SA, Hardy DG. The outcome of radical surgery and postoperative radiotherapy for squamous carcinoma of the temporal bone. Laryngoscope 2005;115:341–7.

- Lionello M, Stritoni P, Facciolo MC, Staffieri A, Martini A, Mazzoni A, Zanoletti E, Marioni G. Temporal bone carcinoma. Current diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic concepts. J Surg Oncol 2014; 110:383–92.

- Parson H, Lewis JS. Subtotal resection of the temporal bone for cancer of the ear. Cancer 1954;7:995–1000.

- Conley JJ, Novack AJ. The surgical treatment of malignant tumors of the ear and temporal bone. Arch Otolaryngol 1960;71:1575–9.

- Lewis JS. Temporal bone resection. Review of 100 cases. Arch Otolaryngol 1974;101:23–5.

- Moore MG, Deschler DG, McKenna MJ, Varvares MA, Lin DT. Management outcomes following lateral temporal bone resection for ear and temporal bone malignancies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137:893–8.

- Dean NR, White HN, Carter DS, Desmond RA, Carroll WR, McGrew BM, et al. Outcomes following temporal bone resection. Laryngoscope 2010;120:1516–22.

- Prasad SC, D’Orazio F, Medina M, Bacciu A, Sanna M. State of the art in temporal bone malignancies. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;22:154–65.

- Gidley PW, Roberts DB, Sturgis EM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone. Laryngoscope 2010;120:1144–51.

- Rinaldo A, Ferlito A, Suarez C, Kowalski LP. Nodal disease in temporal bone squamous carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol 2005; 125:5–8.

- Moody AS, Hirsch BE, Myers EN. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal: an evaluation of a staging system. Am J Otol 2000;21:582–8.

- Mazzoni A, Danesi G, Zanoletti E. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal: surgical treatment and long-term outcomes. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2014;34:129–37.

- Prasad S, Janecka JP. Efficacy of surgical treatments for squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: a literature review. . Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;110:270–80.

- Kinney SE. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Am J Otol 1989;1:111–16.

- Zanoletti E, Marioni G, Stritoni P, Lionello M, Giacomelli L, Martini A, et al. Temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma: analyzing prognosis with univariate and multivariate models. Laryngoscope 2014;124:1192–8.

- Zanoletti E, Marioni G, Franchella S, Lovato A, Giacomelli L, Martini A, et al. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: critical analysis of cases with a poor prognosis. Am J Otolaryngol 2015;36:352–5.

- Clark LI, Narula AA, Morgan DA, Bradley PJ. Squamous carcinoma of the temporal bone: A revised staging. J Laryngol Otol 1991;105:346–8.

- Zanoletti E, Lovato A, Stritoni P, Martini A, Mazzoni A, Marioni G. A critical look at persistent problems in the diagnosis, staging and treatment of temporal bone carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:821–6.

- Dahmani-Causse M, Marx M, Deguine O, Fraysse B, Lepage B, Escudé B. Morphologic examination of the temporal bone by cone beam computed tomography: comparison with multislice helical computed tomography. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2011;128:230–5.

- Nakagawa T, Kumamoto Y, Natori Y, Shiratsuchi H, Toh S, Kazaku Y, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal and middle ear: an operation combined with preoperative chemoradiotherapy and free surgical margin. Otol Neurotol 2006;27:242–9.