Abstract

Traditionally, peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) was regarded as an untreatable condition; however, the introduction of locoregional therapies combining cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) approximately two decades ago has changed this view. There is controversy, however, when a PC arises from pancreatic cancer. We have reported on an extraordinary case of an aggressive pseudomixoma peritonei arising from an invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) treated with complete cytoreduction and HIPEC. This combination of treatments has not been previously described. Moreover, a very long-term disease-free survival of up to 70 months has been achieved by this combined approach. This approach may provide some optimism for considerable life extension in selected patients who present with an aggressive peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis of pancreatic origin considered suitable only for palliative care.

Introduction

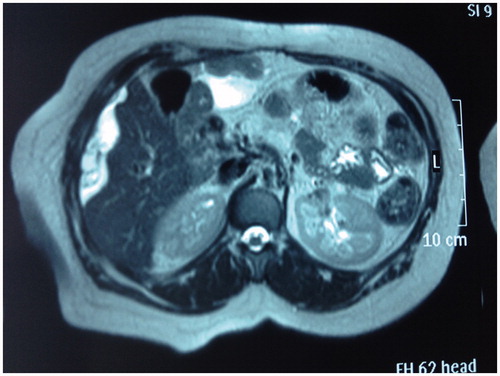

A 63-year-old woman diagnosed with peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis of pancreatic origin by another hospital was submitted to our unit for evaluation for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). She had undergone spleen-sparing total pancreatectomy in another hospital in March 2006 for an invasive main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) (according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification) associated with focal invasive carcinoma in the pancreatic tail. No adjuvant chemotherapy was administered, and follow-up with computed tomography (CT) scan and clinical evaluation was planned every 3 months for the first 2 years. Fifteen months after the initial surgery, she was diagnosed with mucinous peritoneal relapse by magnetic resonance imaging which showed mucinous ascites with several peritoneal implants (). A pathology study was performed by fine needle aspiration, and mucinous carcinoma of probable pancreatic origin was confirmed. The patient was then referred to our unit where she underwent CRS (completeness of cytoreduction = 0 (CC-0)) and HIPEC in March of 2008.

Figure 1. Axial T2 MR imaging: mucinous ascites with several peritoneal implants. White arrow shows the mucinous ascites over the liver surface.

The intra-operative findings were: mucinous ascites, several peritoneal implants involving the upper-mid abdomen, bilateral parietal peritoneum, and both hemidiaphragmatic peritoneums, omental cake, tumoural implants over the splenic capsule, Glisson’s capsule, and lesser omentum; and miliary lesions of the mesentery, the defunctionalised intestinal loop and the pelvic peritoneum, thus receiving a peritoneal cancer index of 20/39. Findings related to the previous surgery were total pancreatectomy and cholecystectomy.

The procedure involved complete parietal peritonectomy (bilateral diphragmatic, bilateral parietal and pelvic peritonectomy), splenectomy, greater and lesser omentectomy, hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, appendectomy, extirpation and ball-tip electroevaporation of mesentery and Glisson’s capsule tumours, and para-aortic and iliac lymphadenectomy.

After achieving complete cytoreduction (CC-0), we administered HIPEC with mitomycin C (30 mg), 42 °C, 60 min in continuous perfusion in 4000 mL of 1.5% dextrose solution. The patient was discharged on post-operative day 12 without morbidity.

Pathological findings: Mesentery and mesocolon abundant with pathological mucinous deposits and short neoplastic epithelial structures, greater omentum, both hemidiaphragmatic peritoneums, bilateral parietal peritoneums, round hepatic ligament, Glisson’s capsule and pelvic peritoneum widely infiltrated by moderately differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma compatible with pancreatic origin, abundant mucin deposits, ileocecal appendix without pathological findings and with no evidence of tumour, para-aortic and bilateral iliac lymph nodes without tumour infiltration.

Immunochemistry

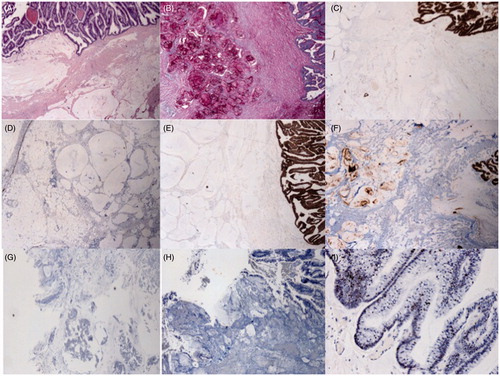

The epithelium was cytokeratin CK7 weak-irregular positive, but CK17 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were strongly positive; CK20 and cancer antigen CA125 were negative; p53 showed nuclear positivity in only half of the tumour cells; compatible with pancreatic origin ().

Figure 2. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin-stained section from tumour tissue in the abdominal cavity: there is extensive dissection of mucous material in the adipose tissue and mucinous epithelium with little nuclear atypia (20×). (B) The mucous material is positive with PAS-diastase and (C) MUC4. The epithelium (D) is CK7 weak-irregular positive but (E) CK17 and (F) CEA strongly positive; (G) CK20 and (H) CA125 are negative. (I) p53 shows nuclear positivity in only half of the tumour cells.

Six cycles of capecitabine were administered as adjuvant chemotherapy. The patient received regular follow-up with a CT scan and tumour markers every 6 months during the first 2 years and yearly thereafter up to the present day. CT and tumour markers have been negative for signs of relapse. At the time of writing of this manuscript, the patient is alive and without signs of disease, 70 months after CRS and HIPEC.

Discussion

IPMNs of the pancreas are defined by the WHO as papillary mucin-producing neoplasms with tall columnar, mucin-containing epithelium with or without papillary projections that extend into the main pancreatic duct or its major branches and are referred to as ‘main duct IPMN’ and ‘branch duct IPMN’, respectively. The lesions are divided into four categories according to the WHO classification: slight dysplasia or intraductal papillary mucinous adenoma, moderate dysplasia or borderline malignancy (borderline IPMN), severe dysplasia or intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma in situ (non-invasive IPMN), and invasive carcinoma (invasive IPMN). When more than one pathological type is identified, the tumour is classified according to the worst lesion present. The duct type is classified according to the final pathological findings as main pancreatic duct disease (MPD type), branch pancreatic duct disease (BPD type), or combined type in the case of lesions in both [Citation1].

Although IPMN has a generally favourable prognosis, its recurrence patterns have been established by a retrospective study from Seoul University [Citation2] which concluded that the degree of dysplasia is the only major predictor of recurrence in these patients. In this very large cohort of IPMN tumours, only 68 patients (18.6%) had an invasive IPMN. The recurrence rate in these patients was significantly higher than in patients with high-grade dysplasia IPMN (33.8% vs. 13.3%; p = 0.014). Only 10 (2.7%) of the patients studied had a peritoneal seeding recurrence and these didn’t receive posterior surgical treatment [Citation2]. The recurrence rates in invasive IPMN are highly variable, ranging from 12% to 100%, but in two recent studies the recurrence rates were 33.8% and 38.2% with a median survival of 46 months [Citation2,Citation3]. There is no available data about survival in patients with peritoneal recurrence of invasive IPMN after primary surgery. In an epidemiological study of 2924 patients with pancreatic carcinoma from the Eindhoven Cancer Registry [Citation4], 9.1% had PC at the time of diagnosis, with a median survival of 6 weeks (95% confidence interval 5–7); none of these received surgical treatment.

Traditionally PC has been regarded as an untreatable condition, requiring palliative measures at most, with an invariably fatal outcome. However, the introduction of locoregional therapies combining CRS and HIPEC approximately two decades ago has changed this view.

Furthermore, this treatment strategy has opened up new therapeutic possibilities for selected patients with PC of appendiceal or colorectal origin, with promising results. Very recently, encouraging results have also been published using this technique in patients with PC of gastric [Citation5] and ovarian origins [Citation6]. This has raised the question of whether other types of cancer associated with PC may also respond to HIPEC. For example, HIPEC could potentially be useful in pancreatic cancer where the peritoneal cavity is a frequently encountered metastatic site and, although this is a well-recognised negative factor for survival, relatively little is known about the incidence, prognosis, and treatment options for this condition. Two case series have described an exclusively surgical approach, combining resection of the primary tumour with radical debulking of the peritoneal deposits. Both groups conclude that such an approach may be feasible but results in a high complication rate without improving survival. Inspired by the results obtained by combining radical surgery with HIPEC in patients with colorectal cancer, Farma et al. [Citation7] performed this procedure in seven patients with PC of pancreatic origin, using heated cisplatin for 90 min. Although the reported median survival of 16 months compares favourably with untreated PC of pancreatic origin and may give rise to some optimism, unfortunately the high incidence of disabling post-operative morbidity led the authors to conclude that such treatment should not currently be offered.

CRS and HIPEC are accompanied by high rates of morbidity and mortality and should be performed only for selected patients in specialised centres where the morbidity rates range from 12% to 52% and the mortality rates range from 0.9% to 5.8% [Citation8]. The inverse relationship between hospital volume and surgical mortality has been well documented in various large-scale population studies. In these studies, factors associated with major morbidity include performance status, extent of carcinomatosis, duration of surgery, number of peritonectomy procedures performed, number of anastomoses, extent of cytoreduction, number of suture lines and dose of chemotherapy [Citation9]. Although locoregional administration of chemoperfusate should reduce the risk of systemic complications of the chemotherapy agent, haematological toxicity and renal insufficiency still remain a problem. These morbidity rates are similar to other major surgeries such as the Whipple procedure, but CRS and HIPEC offer a considerably greater hope of longer-term survival in selected patients with peritoneal surface malignancy. If untreated, many of these patients would succumb to their disease within 6 months, and the terminal phase of their illness would be marked by severe pain due to ascites and bowel obstruction. In the absence of a more efficacious and proven method of treating PC, in which tumour biology still poses a significant challenge, the risks of perioperative morbidity and mortality, which are analogous to any other major gastrointestinal surgery (i.e. the Whipple procedure), need to be weighed against the survival benefit. CRS and HIPEC should remain an option for selected patients who are suitable candidates for this treatment and in whom a curative and life-prolonging treatment is desired in order to avoid and delay the inevitable end of this rapidly progressive terminal condition [Citation8,Citation9].

We have described an extraordinary and carefully selected case of mucinous carcinomatosis arising from an invasive IPMN treated with complete cytoreduction and HIPEC. The patient was a suitable candidate with no exclusion criteria to undergo this procedure in our specialised oncologic surgery unit where we perform more than 70 such procedures per year with morbidity and mortality rates of approximately 18.4% and 0.4% respectively [Citation10]. This specific combination of treatments has not been previously described for this disease, and a very long-term disease-free survival of at least 70 months has been achieved in this case. Consequently, we propose that it should be mandatory to submit these patients to a reference centre with a specialised oncologic surgery unit, particularly since the initial treatment of this patient in her hospital of origin was insufficient; in an invasive main duct IPMN, total pancreatectomy with splenectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy might have been indicated.

The treatment approach described in this manuscript may provide some hope for considerable life extension in selected patients with aggressive peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis of pancreatic origin, rather than considering such patients as candidates only for palliative care. This study was limited by its retrospective design, its performance at a single centre and its size of one patient, and a large-scale multicentre study should be planned to further evaluate our findings.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang J-Y, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2012;12:183–97

- Kang MJ, Jang JY, Lee KB, Chang YR, Kwon W, Kim S-W. Long-term prospective cohort study of patients undergoing pancreatectomy for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: Implications for postoperative surveillance. Ann Surg 2014;260:356–63

- Passot G, Lebeau R, Hervieu V, Ponchon T, Pilleul F, Adham M. Recurrences after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: A single-center study of recurrence predictive factors. Pancreas 2012;41:137–41

- Thomassen I, Lemmens VEPP, Nienhuijs SW, Luyer MD, Klaver YL, de Hingh IHJT. Incidence, prognosis, and possible treatment strategies of peritoneal carcinomatosis of pancreatic origin: A population-based study. Pancreas 2013;42:72–5

- Yarema RR, Ohorchak MA, Zubarev GP, Mylyan YP, Oliynyk YY, Zubarev MG, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion in combined treatment of locally advanced and disseminated gastric cancer: Results of a single-centre retrospective study. Int J Hyperthermia 2014;30:159–65

- Deraco M, Baratti D, Laterza B, Balestra MR, Mingrone E, Macr A, et al. Advanced cytoreduction as surgical standard of care and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy as promising treatment in epithelial ovarian cáncer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2011;37:4–9

- Farma JM, Pingpank JF, Libutti SK, Bartlett DL, Ohl S, Beresneva T, et al. Limited survival in patients with carcinomatosis from foregut malignancies after cytoreduction and continuous hyperthermic peritoneal perfusion. J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:1346–53

- Chua T, Yan TD, Saxena A, Morris DL. Should the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy still be regarded as a highly morbid procedure? Ann Surg 2009;249:900–7

- Glehen O, Gilly F, Boutitie F, Bereder JM, Quenet F, Sideris L, et al. Toward curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-ovarian origin by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intrapertoneal chemotherapy. Cancer 2010;116:5608–18

- Arjona-Sanchez A, Muñoz-Casares FC, Casado-Adam A, Sanchez-Hidalgo JM, Ayllon Teran MD, Orti-Rodriguez R, et al. Outcome of patients with aggressive pseudomyxoma peritonei treated by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Surg 2013;37:1263–70