Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and outcomes of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in treating elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Patients and methods: This was a retrospective analysis of 391 patients with HCC fitting the Milan criteria and treated with RFA for the first time from 1999 to 2012 at the Southwest Hospital, China. The patients were divided into two groups, an elderly group (age ≥70 years, n = 102) and a non-elderly group (age <70 years, n = 289). Long-term outcomes were assessed on all patients and survival rates were calculated.

Results: The overall survival rates of the two groups differed significantly. The recurrence-free survival rates of the two groups did not differ significantly. There was no significant difference between the two groups. Excluding comorbid diseases related deaths, the overall survival rates of the two groups did not differ significantly.

Conclusions: The safety and outcomes of RFA in treating early HCC were similar among elderly and non-elderly patients. Co-morbid diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and respiratory disease, rather than HCC or liver diseases, contributed to the relatively low overall survival rate found in elderly patients.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide. Each year there are approximately 750,000 new HCC cases worldwide and China accounts for 55% of all HCC patients in the world [Citation1]. The causes of HCC are complex. Common risk factors for HCC include Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol and the rising incidence of fatty liver disease. Recent studies have shown that age, gender, and alcohol use are risk factors for HCC. As the average life expectancy continues to improve, the world population will gradually age, and the proportion of elderly patients with HCC will gradually increase [Citation2–4]. In China the average life expectancy has reached 74 years, and the ratio of HCC patients aged over 70 years increases daily. Therefore safer effective treatments are needed for elderly HCC patients.

Rossi et al. [Citation5] first used radiofrequency ablation (RFA) to treat HCC in 1993. RFA technology has undergone steady improvement and is now widely used in the treatment of liver cancer [Citation6]. RFA has the advantage of being minimally invasive and safe. RFA may be an option for patients who are over 70 years of age [Citation7]. The use of RFA in elderly patients with HCC has not yet been tested. The overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) of elderly HCC patients has been reported to be lower than that of younger patients [Citation8–10], while other studies showed no difference in survival [Citation11,Citation12]. Different selection criteria were used to select patients in these studies, but RFA was not considered to be a curative therapy for the patients with HCC beyond the Milan criteria [Citation13,Citation14]. Therefore we used the Milan criteria to select patients from all HCC patients treated with RFA in the past 13 years. A retrospective analysis was performed of 391 patients with HCC treated with RFA initially from June, 1999 to December, 2012 (289 cases <70 years old, 102 cases ≥70 years old).

Patients and methods

Patient information

A total of 2,505 patients with HCC were treated using RFA from June, 1999 to December, 2012 at our hospital. Of these patients, 1,067 had new onset HCC and 411 fulfill the Milan criteria; 20 (4.87%) patients were lost to follow-up and excluded; 391 patients with 438 lesions met the study criteria; 351 patients had a single tumour, 33 had two tumours, and seven had three tumours. There were 345 male and 46 female patients (male to female ratio 7.5:1). The elderly group (≥70 years old, range 70–86 years) included 102 patients. Their mean age was 74.18 ± 3.80 years. The non-elderly group (<70 years old, range 21–69 years) included 289 patients. Their mean age was 48.15 ± 11.33 years. All patients were suitable for RFA [Citation14] and signed written informed consent. Surgical resection and RFA treatments were explained to the patients who were suitable for both of them. These patients chose RFA treatment voluntarily. This consent procedure and this study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Southwest Hospital, which is the affiliated hospital of the Third Military Medical University.

HCC diagnosis

All patients were diagnosed with HCC according to the hepatocellular carcinoma treatment guidelines issued by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) [Citation15]. Common imaging tests included a four-phase multidetector CT, and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Clinical diagnosis of HCC was based on the patient’s history of chronic liver disease and typical HCC manifestations revealed by imaging examinations (hypervascular liver lesions in the arterial phase with washout in the portal veins or in the delayed phase). A total of 290 patients were diagnosed from radiological findings and 101 from percutaneous liver biopsy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were clinically diagnosed or pathologically diagnosed HCC that fitted the Milan criteria (a single HCC ≤5 cm in diameter or up to three lesions ≤3 cm in diameter), Child–Pugh grade A or B liver function, and no previous treatment of the HCC. Exclusion criteria were other anti-cancer treatments before RFA (surgery, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy), other neoplastic diseases, severe organ dysfunction, severe coagulopathy and refractory ascites that could not be improved with treatment, hepatic encephalopathy, and inadequate follow-up.

Basic clinical information

Disease history-taking, and preoperative examinations and evaluations were performed after hospital admission. Of the total, 328 patients (83.89%) had viral hepatitis (324 with HBV, four with HCV). The proportion of patients with co-morbid diseases in the elderly group was significantly higher than that in the non-elderly group (χ2 = 54.949, p < 0.001). (). All patients’ data were extracted from the medical record library of Southwest Hospital. Three experts at the clinical research centre of Southwest Hospital extracted patients’ data and checked for accuracy.

Table 1. Characteristics of two groups treated by radiofrequency ablation.

RFA technique

Percutaneous liver biopsy was performed prior to RFA. We used the disposable core biopsy instrument (Bard Peripheral Vascular, Tempe, AZ, USA) with a gauge size and needle length of 14G × 16 cm. Under the guidance of ultrasound, the biopsy needle was inserted into the normal tissue 2 cm beyond the edge of the tumour. Liver tissue specimens with a length of 1.9 cm were obtained by ejection. Then the biopsy needle was inserted into the lesions and tumour specimens of the same length were obtained. Pathological examination was performed on specimens. Percutaneous RFA was performed in all patients using the LDRF-120S RF ablation device (Lead Electron, Mianyang, China) and Elektrotom 106 HiTT minimally invasive surgery system (Berchtold Medizin Electronik, Tuttlingen, Germany). Four senior experts performed the RFA (each had previously treated more than 200 cases). Single needle and retractable/expandable multi-needle electrodes, with saline infusion incorporated, were used. A 4–5-cm diameter ablation volume could be achieved with a single ablation. The puncture site was determined under ultrasound or contrast-enhanced ultrasound guidance [Citation16]. All surgery was performed under monitored anaesthesia care (MAC). A single-needle electrode was inserted in the inferior aspect of the tumour. The multi-needle electrode was opened after the tine was advanced, the open cluster electrode was 1 cm beyond the edge of the tumour. In this study, 199 lesions were treated with single-needle electrode and 239 lesions were treated with multi-needle electrodes. The starting power was set to 50 W, and then increased by 10 W every 2 min until reaching a maximum power of 95 W. The maximum power was maintained until the resistance reached its maximum value. Electrode position was adjusted and treatment repeated until the entire lesion was enveloped by necrotic areas [Citation17]. Vital signs were monitored during treatment.

Post-operative evaluation

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (US) or contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was performed the day after treatment. Contrast-enhanced US was performed on 115 patients, contrast-enhanced CT was performed on 209 patients, both of them were performed on 67 patients. After treatment, the ablation area appeared as an echo-free zone on contrast-enhanced US, or a low-density area on contrast-enhanced CT. The ablation area and the safety margin (SM), the margin of normal tissue ablated around the tumour, were measured. Residual tumours were found on 18 patients, all of them were retreated with RFA during the same hospitalisation.

Follow-up

Patients were evaluated 1 month after treatment, and then every 2 months for 1 year, and every 3 months after 1 year. Serum a-fetoprotein (AFP), HBV-DNA, and imaging tests (multi-detector CT and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, performed with intravenous contrast material) were performed at each visit. Multi-detector CT was performed at all visits, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI was performed at 93 visits. Treatment received after relapse and cause of death were also collected. The number of patients dying of HCC or liver disease and co-morbid diseases were calculated respectively. Patients were followed until death. The duration of the follow-up ranged 8–79 months.

Diagnosis of HCC recurrence

Recurrences included local tumour progression (LTP), intrahepatic recurrence, and extrahepatic metastasis [Citation14]. LTP was defined as recurrence contiguous to the original ablation area [Citation4]. Patients were followed up with 4-phase multi-detector CT imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. If the imaging tests did not confirm the diagnosis, the treatment site (23 patients) was biopsied.

Statistical methods

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or proportion of patients. A Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables, A Fisher’s exact test was used to compare non-continuous variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate cumulative overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) rates. A log-rank test was used to compare OS and RFS rates and performed for univariate analyses. A Cox proportional hazard model was used for multivariate analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Treatment efficacy

Complete ablation of all lesions was achieved. All patients recovered and there was no death after RFA during the same hospitalisation. Post-operative Clavien complication classification [Citation18] was significantly different between the two groups. There were 27 cases (26.47%) in the elderly group and 45 cases (15.57%) in the non-elderly group of Clavien grade II or above, but only one case (0.98%) in the elderly group and seven cases (2.42%) in the non-elderly group of Clavien grade III or above. Complications occurred more often in the elderly group, but the complications were relatively mild.

Survival rates

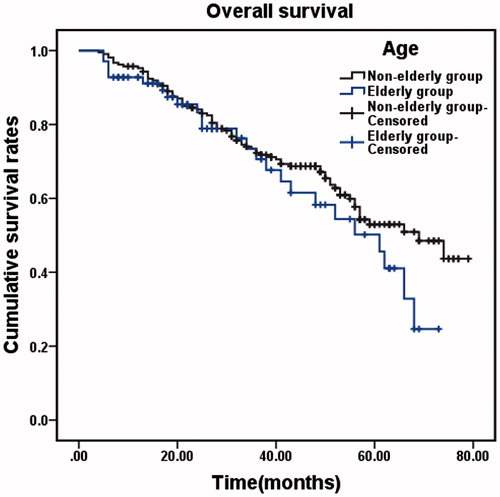

The OS of the elderly group ranged from 4 to 73 months, with a median time of 55 months. The 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 5-year OS rates were 89.21, 78.43, 66.67, 53.92 and 38.24%, respectively. The OS of the non-elderly group ranged from 2 to 79 months, with a median time of 66 months. The 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 5-year OS rates were 94.81, 83.74, 71.97, 66.44 and 52.25%, respectively. The OS rates of the elderly group were significantly lower than those of the non-elderly group (χ2 = 6.450, p = 0.011, ). The RFS time of the elderly group ranged from 2 to 69 months, with a median RFS of 16 months. The 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 5-year RFS rates were 59.80, 36.27, 28.43, 24.51 and 23.53%, respectively. The RFS of the non-elderly group ranged from 2–68 months, with a median RFS of 15 months. The 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 5-year RFS rates were 57.09, 40.83, 31.49, 27.68 and 22.49%, respectively. The two groups did not differ significantly in RFS rate (χ2 = 0.038, p = 0.844, ).

Figure 1. Overall survival and recurrence-free survival in the elderly and non-elderly groups. (A) Cumulative OS rates in the elderly group (n = 102) and the non-elderly group (n = 289). There was a significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 6.450, p = 0.011, log-rank test). (B) Cumulative RFS rates in the two groups. There was no significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 0.038, p = 0.844, log-rank test).

Univariate analysis of factors influencing survival

Univariate analysis identified 12 factors that significantly influenced OS survival in the elderly group and 10 factors in the non-elderly group. Viral infection (HBV or HCV), Child–Pugh grade B, tumour size >3 cm, cirrhosis, platelet count <100 × 109/L, and positive HBV-DNA were significant factors shared by both groups. Excessive alcohol consumption, safety margin <5 mm, white blood cell <4 × 109/L, serum creatinine (Cr) >88.4 μmol/L and co-morbid diseases were significant risk factors specific to the elderly group. Nine factors significantly influenced the RFS survival in the elderly group, and 10 factors in the non-elderly group. Excessive alcohol consumption, viral infection (HBV or HCV), hypervascularity, tumour size >3 cm, safety margin <5 mm, cirrhosis, ALT >40 U/L, AFP >20 ng/mL, and HBV-DNA (positive) were significant factors shared by both groups ().

Table 2. Univariate analysis of the risk factors for overall survival and recurrence-free survival.

Multivariate analysis of factors influencing survival

The multivariate analysis identified five factors significantly affecting OS in the elderly group and four in the non-elderly group. Viral infection (HBV or HCV), tumour size >3 cm, and Child–Pugh grade B were risk factors shared by both groups. Co-morbid diseases and serum Cr ≥88.4 μmol/L were risk factors specific to the elderly group. Six factors significantly affected RFS. Viral infection (HBV or HCV), tumour size >3 cm, safety margin <5 mm and AFP >20 ng/mL were factors shared by both groups ().

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of the risk factors for overall survival and recurrence-free survival.

HCC recurrence and retreatment

A total of 271 (69.31%) patients had confirmed HCC relapse, including 68 (66.67%) in the elderly group and 203 (70.24%) in the non-elderly group; 91 (23.27%) patients had LTP, including 23 (22.55%) in the elderly group and 68 (23.53%) in the non-elderly group (χ2 = 0.041, p = 0.892); 149 (38.11%) patients had intrahepatic recurrences, including 31 (30.39%) in the elderly group and 118 (40.83%) in the non-elderly group (χ2 = 3.483, p = 0.075); 31 patients (7.93%) had HCC metastases, including 14 (13.73%) in the elderly group and 17 (5.88%) in the non-elderly group (χ2 = 5.942, p = 0.020); 259 patients (66.24%) were treated for HCC recurrence. Among them, 88 patients (22.51%) received RFA repeatedly (twice or more). Four patients had seven RFA treatments each. The OS of these four patients were all above 36 months.

Cause of death

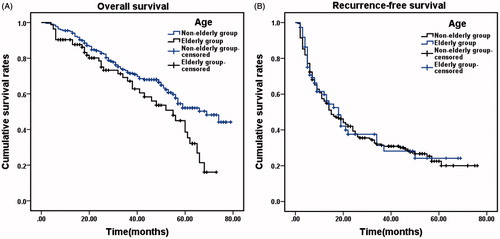

A total of 158 (40.41%) patients died during follow-up, including 47 (46.08%) in the elderly group and 111 (38.41%) in the non-elderly group (χ2 = 1.842, p = 0.197); 98 (25.06%) died from HCC recurrences and metastases (21 (20.59%) in the elderly group and 77 (26.64%) in the non-elderly group, χ2 = 1.472, p = 0.235). 17 (4.35%) died from liver failure (three (2.94%) in the elderly group and 14 (4.84%) in the non-elderly group, χ2 = 0.657, p = 0.576). 12 (3.07%) died from upper gastrointestinal bleeding (two in the elderly group (1.96%) and 10 in the non-elderly group (3.46%), χ2 = 0.570, p = 0.739); 31 (7.93%) died from co-morbid diseases (21 (20.59%) in the elderly group and 10 (3.46%) in the non-elderly group, χ2 = 30.299, p < 0.001). Excluding deaths from co-morbid diseases, the 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rates of the elderly group (n = 81) and the non-elderly group (n = 279) were 91.36%, 70.37%, 48.15% and 95.34%, 73.48%, 52.33%, respectively. There was no significant difference in the two groups (χ2 = 1.632, p = 0.201, ). Excluding deaths from co-morbid diseases, the OS rate of the elderly group was comparable to that of the non-elderly group.

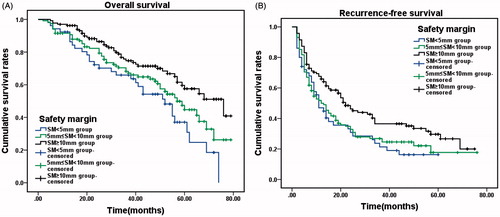

Subgrouping based on safety margin

Patient outcomes were evaluated by treatment margin. Patients were divided into a safety margin (SM) <5 mm subgroup (n = 67), 5 mm ≤ SM <10 mm subgroup (n = 175), and SM ≥10 mm subgroup (n = 149). The 1-, 3- and 5-year OS of the three subgroups were: SM <5 mm subgroup, 91.04%, 64.18% and 31.34%, respectively, 5 mm ≤ SM <10 mm subgroup, 90.86%, 68.57% and 44.57%, respectively, and SM ≥10 mm subgroup, 96.64%, 74.50% and 57.72%, respectively. There was a significant difference in the OS of the three subgroups (χ2 = 10.899, p = 0.004, ). The 1-, 3- and 5-year RFS of the three subgroups were: SM <5 mm subgroup, 46.27%, 22.39% and 14.93%, respectively; 5 mm ≤ SM <10 mm subgroup, 50.86%, 26.29% and 17.14%, respectively; and SM ≥10 mm subgroup, 67.11%, 36.24% and 28.86%, respectively. There was a significant difference in the RFS of the three subgroups (χ2 = 8.459, p = 0.015, ).

Figure 3. Overall survival and recurrence-free survival in all patients, according to safety margin (SM). (A) Cumulative OS rates in the SM < 5 mm group (n = 67), 5 mm ≤ SM <10 mm group (n = 175) and SM ≥ 10 mm group (n = 149). There was a significant difference between the three groups (χ2 = 10.899, p = 0.004, log-rank test). (B) Cumulative recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates in the three groups. There was a significant difference between the three groups (χ2 = 8.459, p = 0.015, log-rank test).

Discussion

Using the Milan criteria to select patients, the dates in this study were consecutive, it was the largest study of its type, and had the longest duration of follow-up. All treatments were performed by four experienced operators in the same medical centre, using the same treatment parameters. At the time of writing there are few similar reports. An article by Hiraoka et al. [Citation19] also discussed elderly HCC within Milan criteria undergoing RFA in Japan. In his study, the patients were mainly infected by HCV (167/206, 81.07%), but the patients were mainly infected by HBV in our study (325/391, 83.12%). HBV infection is the leading cause of HCC in China. The patient populations were different in the two studies. In addition, the conclusions were obviously different in the two studies. We found the OS rates of the elderly patients were significantly lower than non-elderly patients because of co-morbidities, but in Hiraoka’s study, there was no significant difference in their two groups. Furthermore, our study had a larger number of cases and longer duration of follow-up.

The Milan criteria were developed in the 1990s to define patients with early stage HCC [Citation20]. HCC patients who fit the Milan criteria have a relatively good prognosis after liver transplantation and surgical resection. Five-year RFS after surgery is 51.30% and 5-year OS, 75.65% [Citation21]. High cost and limited supply of livers for transplant prevent most patients from utilising this treatment, especially patients older than 70 years. The majority of these elderly patients have co-morbidities, poor physical condition, and are not good surgical candidates. Surgical treatment of elderly patients (age ≥70 years) with HCC is associated with high incidence of complications and death [Citation22,Citation23]. There is often a limited choice of treatments. RFA is minimally invasive, safe, easy to implement and affordable [Citation24]. HCC with diameters of 3 cm or less are ideal for this treatment [Citation25]. RFA has improved electrodes, larger volumes of treatment with a single ablation, and the ability to ablate liver tumours 5 cm or less in diameter [Citation24].The long-term efficacy of RFA is comparable to that of surgical treatment and liver transplantation [Citation17,Citation26,Citation27]. RFA has been used as the preferred treatment option for small HCC or elderly patients with HCC [Citation28–30].

Post-operative complications can have a significant effect on overall survival, and reducing post-operative complications can improve survival [Citation31,Citation32]. Age >70 years has been reported to be a significant risk factor for serious systemic complications after hepatic resection. The incidence of post-operative complications and mortality after RFA are significantly lower than after surgical resection, especially in elderly patients [Citation23,Citation27,Citation33]. In this study, complications occurred more often in the elderly group, but we found no serious complications or deaths after RFA. The proportion of Clavien grade III and above in two groups was of no significant difference (χ2 = 0.490, p = 0.686). We feel that RFA is relatively safe for treating elderly patients with HCC.

The reported 5-year OS of patients with HCC treated with RFA ranged from 42.9% to 70%, and the 5-year RFS ranged from 10.6% to 28.69% [Citation8,Citation21,Citation34–36]. Our OS of the elderly group was significantly lower than that of the non-elderly group, and that was reported, but the two groups did not differ significantly in RFS rate. The factors affecting the OS of elderly patients were more than non-elderly patients. A number of factors were not related to the cancer or liver disease in the univariate analysis of the elderly HCC patients. These factors included cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and serum creatinine >88.4 μmol/L. Also, the life expectancy of elderly patients is relatively short. With longer follow-up, the difference in OS between the elderly and non-elderly becomes even more substantial. Different inclusion criteria have been used in previously reported studies, resulting in wide difference in survival rates after RFA. Some studies included HCC patients with tumours less than 3 cm in diameter [Citation9]. This criterion is too stringent, excluding many patients from treatment. Some studies treated a single lesion of any size or up to five lesions no larger than 3 cm [Citation11]. This volume of tumour is more difficult for radiofrequency treatments to completely ablate. Many reports have documented the lower OS rate in elderly patients after RFA, and that elderly co-morbidities are a significant factor influencing survival. These co-morbidities were not censured in these analyses [Citation4,Citation8–10]. We found that excluding death from co-morbidities resulted in a similar 5-year OS in both age groups. The post-operative OS of elderly patients was affected by a large number of factors, and a straightforward comparison with non-elderly patients was not appropriate. The effect of age on RFS is controversial. Many studies have shown that old age did not influence RFS after RFA for HCC [Citation9,Citation11,Citation37]. Moreover, hepatitis virus infection and lesion size affected RFS and OS in both age groups in the multivariate analysis. There are over 100 million carriers of HBV in China, is the leading cause of HCC, and contributes to HCC recurrence and death in patients with HCC. HBV-DNA positive patients have a poor prognosis, but routine post-operative antiviral therapy after RFA may improve patient survival [Citation10].

Ablation of the tumour with a suitable margin of normal tissue is needed to obtain the optimal RFS and it is the key to improving survival [Citation38,Citation39]. We performed subgroup analyses based on safety margin. The OS and RFS of the SM ≥ 10 mm subgroup were significantly higher than the other subgroups. The SM <5 mm subgroup had 23 patients with LTP, significantly higher than the other subgroups (χ2 = 5.533, p = 0.026, Fisher’s exact test). HCC are often associated with micrometastases or microvascular invasion. The larger the tumour diameter, the larger the range of peri-tumoural infiltration, and a larger number of peri-tumoural micrometastases also occur [Citation40,Citation41]. We found that tumour size and safety margin are key factors in post-operative recurrence. In the procedure, the ablation range was designed to be 10 mm beyond the edge of the tumour. However, because of the location of the lesions (abutting the main bile duct and blood vessel) [Citation42–44], we could not obtain a safety margin greater than 10 mm on all patients. Most of the patients (175/391, 44.76%) only obtained a safety margin between 5 mm and 10 mm. But the OS and RFS of the 5–10-mm subgroup are still higher than the SM <5 mm subgroup. Therefore, we want to say a larger safety margin predicted better prognosis.

Multiple RFA treatments have been used to control tumour progression [Citation45] and treat recurrent HCC, achieving similar outcomes to those of patients with new onset HCC [Citation46]. But combined treatment regimens may yield better outcomes. RFA combined with TACE has been reported to be significantly better than either of the treatments alone [Citation47]. Therefore, a comprehensive treatment plan should be developed based on the patient’s physical condition, HCC status, expectations and financial ability. We believe that RFA is safe and minimally invasive, making it a relatively good choice for treating recurrent HCC in elderly patients.

Conclusions

In summary, HCC patients fitting the Milan criteria and treated with RFA have satisfactory outcomes of tumour ablation and survival. The safety and prognosis of elderly patients was similar to that of non-elderly patients. Co-morbid diseases, but not the HCC or liver diseases, contributed to the relatively low post-operative OS rate in elderly patients.

Declaration of interest

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (project nos. 81272688 and 30972894), the medical research program of Chongqing Health Bureau (no. 2013-2-307), and the clinical innovation fund of the Third Military Medical University (no. 02009XLC11). The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Chen Shu and all the medical staff at the clinical research centre of the Southwest Hospital, the medical record library of Southwest Hospital, and the anonymous reviewers for their excellent advice.

References

- Shenglong Y, Shukui Q. Expert consensus on standardization of the management of primary liver cancer. Chin J Hepatol 2009;29:295–304

- Golfieri R, Bilbao JI, Carpanese L, Cianni R, Gasparini D, Ezziddin S, et al. Comparison of the survival and tolerability of radioembolization in elderly vs younger patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2013;59:753–61

- McKenna RJ, Sr. Clinical aspects of cancer in the elderly. Treatment decisions, treatment choices, and follow-up. Cancer 1994;74:2107–17

- Nishikawa H, Osaki Y, Iguchi E, Takeda H, Ohara Y, Sakamoto A, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Clinical outcome and safety in elderly patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2012;21:397–405

- Rossi S, Di Stasi M, Buscarini E, Quaretti P, Garbagnati F, Squassante L, et al. Percutaneous RF interstitial thermal ablation in the treatment of hepatic cancer. Am J Roentgenol 1996;167:759–68

- Nishikawa H, Kimura T, Kita R, Osaki Y. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Hyperthermia 2013;29:558–68

- Bove A, Bongarzoni G, Di Renzo RM, Marsili L, Chiarini S, Corbellini L. Efficacy and safety of ablative techniques in elderly HCC patients. Ann Ital Chir 2011;82:457–63

- Waki K, Aikata H, Katamura Y, Kawaoka T, Takaki S, Hiramatsu A, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation as first-line treatment for small hepatocellular carcinoma: Results and prognostic factors on long-term follow up. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:597–604

- Toshikuni N, Takuma Y, Goto T, Yamamoto H. Prognostic factors in hepatitis C patients with a single small hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Hepatogastroenterology 2012;59:2361–6

- Kao WY, Chiou YY, Hung HH, Su CW, Chou YH, Huo TI, et al. Younger hepatocellular carcinoma patients have better prognosis after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46:62–70

- Takahashi H, Mizuta T, Kawazoe S, Eguchi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Otuka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation for elderly hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatol Res 2010;40:997–1005

- Kondo K, Chijiiwa K, Funagayama M, Kai M, Otani K, Ohuchida J. Hepatic resection is justified for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 2008;32:2223–9

- Sala M, Llovet JM, Vilana R, Bianchi L, Solé M, Ayuso C, et al. Initial response to percutaneous ablation predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2004;40:1352–60

- Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (V2011). Chin J Clin Hepatol 2011;27:1141–59

- EASL-EORTC. Clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908–43

- Liu F, Yu X, Liang P, Cheng Z, Han Z, Dong B. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound-guided microwave ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma inconspicuous on conventional ultrasound. Int J Hyperthermia 2011;27:555–62

- Feng K, Yan J, Li X, Xia F, Ma K, Wang S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;57:794–802

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13

- Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Horiike N, Hidaka S, Uehara T, Ichikawa S, et al. Radiofrequency ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:403–7

- Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693–9

- Huang J, Yan L, Cheng Z, Wu H, Du L, Wang J, et al. A randomized trial comparing radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for HCC conforming to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg 2010;252:903–12

- Lee CR, Lim JH, Kim SH, Ahn SH, Park YN, Choi GH, et al. A comparative analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection in young versus elderly patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:1736–43

- Nanashima A, Abo T, Nonaka T, Fukuoka H, Hidaka S, Takeshita H, et al. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection: Are elderly patients suitable for surgery? J Surg Oncol 2011;104:284–91

- Chen MH, Dong JH. Ablation treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status, pitfalls and future implications. Chin J Hepatol 2012;20:241–4

- Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2006;243:321–8

- Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, et al. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol 2001;35:421–30

- Zhang YJ, Chen MS. Role of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2010;2:146–50

- Peng ZW, Zhang YJ, Chen MS, Lin XJ, Liang HH, Shi M. Radiofrequency ablation as first-line treatment for small solitary hepatocellular carcinoma: Long-term results. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:1054–60

- Choi D, Lim HK, Rhim H, Kim YS, Lee WJ, Paik SW, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma as a first-line treatment: Long-term results and prognostic factors in a large single-institution series. Eur Radiol 2007;17:684–92

- Livraghi T. Single HCC smaller than 2 cm: Surgery or ablation: Interventional oncologist’s perspective. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010;17:425–9

- Mizuguchi T, Nagayama M, Meguro M, Shibata T, Kaji S, Nobuoka T, et al. Prognostic impact of surgical complications and preoperative serum hepatocyte growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after initial hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:325–33

- Okamura Y, Takeda S, Fujii T, Sugimoto H, Nomoto S, Nakao A. Prognostic significance of postoperative complications after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2011;104:814–21

- Sato M, Tateishi R, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, Yoshida H, Matsuda S, et al. Mortality and morbidity of hepatectomy, radiofrequency ablation, and embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: A national survey of 54,145 patients. J Gastroenterol 2012;47:1125–33

- Yan K, Chen MH, Yang W, Wang YB, Gao W, Hao CY, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: Long-term outcome and prognostic factors. Eur J Radiol 2008;67:336–47

- Chan AC, Chan SC, Chok KS, Cheung TT, Chiu DW, Poon RT, et al. Treatment strategy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: Salvage transplantation, repeated resection, or radiofrequency ablation? Liver Transpl 2013;19:411–19

- Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Koike Y, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases. Cancer 2005;103:1201–9

- Nishikawa H, Osaki Y, Iguchi E, Koshikawa Y, Ako S, Inuzuka T, et al. The effect of long-term supplementation with branched-chain amino acid granules in patients with hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency thermal ablation. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:359–66

- Cho YK, Rhim H, Noh S. Radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection as primary treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma meeting the Milan criteria: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26:1354–60

- Zytoon AA, Ishii H, Murakami K, El-Kholy MR, Furuse J, El-Dorry A, et al. Recurrence-free survival after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. A registry report of the impact of risk factors on outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2007;37:658–72

- Kim YK, Kim CS, Lee JM, Chung GH, Chon SB. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma in the hepatic dome with the CT-guided extrathoracic transhepatic approach. Eur J Radiol 2006;60:100–7

- Xueping Z, Guangshun Y, Wenming C, Junhua L, Shuhui Z, Ming Z. Retrospective and prospective study on micrometastasis in liver parenchyma surrounding PLC. Chin J Hepatobiliary Surg 2005;11:510–14

- Sheiman RG, Mullan C, Ahmed M. In vivo determination of a modified heat capacity of small hepatocellular carcinomas prior to radiofrequency ablation: Correlation with adjacent vasculature and tumour recurrence. Int J Hyperthermia 2012;28:122–31

- Huang J, Li T, Liu N, Chen M, He Z, Ma K, et al. Safety and reliability of hepatic radiofrequency ablation near the inferior vena cava: An experimental study. Int J Hyperthermia 2011;27:116–23

- Liu N, Gao J, Liu Y, Li T, Feng K, Ma K, et al. Determining a minimal safe distance to prevent thermal injury to intrahepatic bile ducts in radiofrequency ablation of the liver: A study in dogs. Int J Hyperthermia 2012;28:210–17

- Ikeda K, Kobayashi M, Kawamura Y, Imai N, Seko Y, Hirakawa M, et al. Stage progression of small hepatocellular carcinoma after radical therapy: Comparisons of radiofrequency ablation and surgery using the Markov model. Liver Int 2011;31:692–9

- Yang W, Chen MH, Yan K, Gao W, Yin SS, Wang YB, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Chin J Surg 2005;43:980–4

- Yang W, Chen MH, Wang MQ, Cui M, Gao W, Wu W, et al. Combination therapy of radiofrequency ablation and transarterial chemoembolization in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy compared with single treatment. Hepatol Res 2009;39:231–40