Abstract

Objective. Pregnant women complaining of itching are screened for intrahepatic cholestasis (ICP) by laboratory tests in primary healthcare. Cases of ICP are referred to specialist care. In Finland, ICP occurs in 1% of pregnancies. The aim was to study the outcome of deliveries. Design. Retrospective study of ICP pregnancies. Data were collected from the hospital discharge register, patient records, and the labour register. Setting. The region of Tampere University Hospital in Finland. Subjects. Altogether 687 ICP cases from 1969 to 1988 and two controls for each. Main outcome measures. ICP patients were compared with controls in terms of mother's age, pregnancy multiplicity, weeks of gestation at delivery, frequency of induction and Caesarean section, length of ward period, child's weight, Apgar scores, and stillbirth. Results. For ICP patients, the risk for hospital stay of 10 days or more was eightfold (OR 8.41), for gestational weeks less than 37 at delivery sevenfold (OR 7.02), for induction threefold (OR 3.26), for baby's low weight at birth almost twofold (OR 1.86), and for Caesarean section one and a half fold (OR 1.47). The possibility of the incidence of multiple pregnancy was two and a half fold (OR 2.49, 95%). ICP was not associated with mother's age, the baby's risk of stillbirth, or low Apgar scores. Conclusion. ICP mothers are found and taken care of appropriately, and thus ICP is only a minor risk for mothers and their children.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) contains risks for the foetus. It is important that ICP cases are detected in primary healthcare.

ICP mothers’ ages did not differ significantly from others.

Childbirth happened at earlier weeks of gestation in ICPs, but Apgar scores were only slightly lower.

In ICP cases labour induction and Caesarean section were more common and hospital stay was significantly longer.

In the Nordic countries maternity care is organized almost exclusively within a primary healthcare setting [Citation1]. Deliveries are carried out mainly in hospitals [Citation2]. In Finland midwives or nurses qualified in health nursing and midwifery are the principal staff of maternity clinics in health centres [Citation3,Citation4]. Midwives work with GPs, who are responsible for maternity clinics in health centres. Usually the referral system is organized with hospital maternity outpatient clinic, the same hospital where the delivery will be carried out.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) usually manifests in the third trimester of pregnancy as skin itching and as elevation of the serum levels of bile acids and liver enzymes [Citation5,Citation6]. The incidence of ICP in Finland and Sweden is 0.54–1.5% [Citation7,Citation8,Citation9]. ICP may recur in 40–60% of subsequent pregnancies [Citation5,Citation10]. In 16% of cases ICP is familial, and in those cases ICP recurs in 92% [Citation11]. ICP is more common with mother's age over 35 years [Citation9] and in multiple pregnancy [Citation12,Citation13]. The ultimate reason for ICP is unknown. ICP is thought to be the result of insufficient liver capacity to metabolize high amounts of placental hormones during pregnancy [Citation5,Citation14], and symptoms fade and laboratory tests normalize quickly after the delivery. ICP increases the risk of preterm birth (12–44%) [Citation13,Citation15,Citation16], fetal distress during labour (10-44%) [Citation7,Citation13,Citation15,Citation17], and intrauterine fetal death (1–3%) [Citation7,Citation15,Citation17] may ensue. Bile acids have been shown to induce vasoconstriction of human placental chorionic veins, and myometrial sensitivity to oxytocin [Citation18,Citation19]. In clinical practice, mode and timing of labour and delivery are managed individually to reduce risks for the foetus. ICP is a minor problem for the mother during pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum. It has been stated that women with a history of ICP are more prone to several liver and biliary disorders including non-alcoholic cirrhosis, non-specific hepatitis, hepatitis C, cholelithiasis, and pancreatitis in their life, even before the first occurrence of ICP [Citation20].

According to current guidelines, the GP or midwife in the health centre maternity clinic verifies ICP with laboratory tests if a pregnant woman in her last trimester of pregnancy complains of itching, especially on her palms and soles [Citation21]. When a woman is diagnosed with ICP, she is referred to the hospital maternity outpatient clinic. If itching is intensive and ICP is evident, the patient must be urgently referred to an obstetric clinic even without laboratory tests.

The aim was to study certain characteristics of deliveries with ICP and the outcome of the pregnancies.

Material and methods

ICP pregnancies during 1969–1988 are our focus, because from these data we wanted to study whether ICP has any long-term effects on the lives of mothers and children. The hospital discharge register, labour register, and patient records of Tampere University Hospital (TUH) were available for the study. There were 4000 deliveries yearly on average in the hospital during these 20 years.

ICP patients were searched for from the hospital discharge register according to diagnosis codes. ICD-8 was used in TUH during 1969–1986. Because ICD-8 did not include a precise code for ICP, we observed all the obstetric code numbers that might contain ICP, that is, 637.9 Toxicosis NUD, 639.00 Pruritus, 639.01 Icterus gravis, 639.09 Necrosis acuta et subacuta hepatis and 639.98 Aliae definitae. Thereafter, we checked the written diagnosis behind the code number, and if it referred to ICP we included the case for further selection. ICD-9 was used in 1987–1988 and it contained appropriate codes 6467A Hepatosis gravidarum and 6467X Hepatopathia alia. Finally, the diagnosis was verified from each patient record with the presence of the main symptom of itching and laboratory tests. At least one of the following was required: ASAT > 35 U/l, ALAT > 40 U/l, or bile acids 6 µmol/l or more.

In the hospital discharge register, 971 cases were found with appropriate diagnoses. Of those, 284 cases were dismissed (). We found 575 women who had had ICP at least once. When repeated deliveries were included, we had 687 ICP cases in our study material.

Figure 1. Flow chart of ICP patients and controls in Tampere University Hospital (TUH) during 1969–1988.

For each ICP case, two controls were taken from the labour register, namely the previous and the next woman in the labour register. The outcome measures were mother's age, ongoing week of gestation (e.g. 36+1 was noted as 37 weeks), labour induction, Caesarean section, multiple pregnancy, length of ward period, child's weight at birth, Apgar scores, and stillbirth. In multiple pregnancy matters concerning the child only indicate the first-born child. To avoid selection of outcome measures sought from the labour register, data were collected systematically in the same structured form for ICP cases and controls.

Tampere University Hospital (TUH) takes care of all deliveries in its area. We consider that the control group represents all the almost 80 000 deliveries in TUH during the 20 years from 1969 to 1988. We wanted to compare the pregnancy outcome of the ICP group with the control group, rather than considering individual case-control pairs. Matching of controls to cases is based on coincidence (previous and next in the temporal register in the same hospital), which makes diagnostics and management in the two groups comparable.

The analyses were undertaken using the SPSS System for Windows, release 16.0. The results were presented as frequencies and mean values. The associations between ICP and matters concerning delivery, mother, and the newborn were analysed with logistic regression analyses (OR with 95% CI). Statistical significance was tested by t-test and chi-squared test.

Results

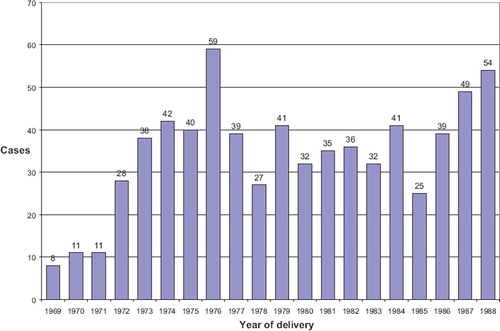

There were about 40 cases of ICP pregnancies during the study period every year (mean 38.6, range 25–59), except for the first three years when the numbers were lower (). The incidence of ICP (n = 687) was 0.9% of all deliveries (n = 79508).

ICP deliveries were compared with controls. In the ICP group, hospital stay was significantly longer (). Mothers’ ages did not differ from controls. Babies’ weights were lower. Apgar scores did not differ in practice.

Table I. Comparison of ICP patients and controls in Tampere University Hospital during 1969–1988: Mean difference in variables.

Labour induction was carried out for almost half of the ICP patients and for one-fifth of the controls, and Caesarean section was more common in ICP cases (). The percentage value of multiple pregnancies was two and a half fold and that of stillbirth almost twofold for ICP pregnancies. Proportion of mothers 35 years or older was slightly lower for ICP mothers.

Table II. Comparison of ICP patients and controls in Tampere University Hospital during 1969–1988: Percentage values of variables.

In the logistic regression analyses mother's age was not associated with ICP (). The risk of premature delivery was sevenfold among ICP patients compared with controls. The risk of induction was threefold and the risk of Caesarean section was one and a half fold. The possibility of the incidence of multiple pregnancies was two and a half fold. The risk of child's low weight at birth was twofold. Low Apgar scores and stillbirth were not associated with ICP. The risk of the duration of hospital stay being at least 10 days was more than eightfold.

Table III. Risk for matters concerning delivery in ICP cases in the univariate logistic regression analyses.

Discussion

Mothers with ICP stayed longer in hospital and more often had labour induction and Caesarean section than controls. Children were born at earlier weeks, but Apgar scores did not differ significantly either at one minute or at five minutes, the latter being more important for the prognosis of the child. Logistic regression analysis showed no significant risk growth in stillbirth, confidence intervals being wide. Stillbirth occurred in 1.2% of ICP cases, which fits with earlier studies (1–3%). In means, the difference in stillbirths was statistically significant. In any case, stillbirth was so infrequent that no ultimate conclusion can be drawn from these data. Power calculation shows that the number of ICP cases should have been 6000 to make conclusions of any significant difference.

Bile acids have been suspected in the case of fetal arrhythmia. In our study the number of stillbirths in which abnormal bile acid levels had been measured in mothers’ blood was very low and showed no systematic trend. Normal bile acid levels were not systematically recorded.

In an earlier study [Citation9], Heinonen and Kirkinen stated that ICP risk was increased by mother's age. In our study the association was not found. We analysed the measured variables using mother's age as continuous variant, and we found no changes in any of the risks.

The material is comprehensive, consisting of ICP cases in a university hospital over a 20-year period. The number of ICP cases found corresponds to the known 0.54–1.5% incidence of ICP. During 1969–1988 the incidence of ICP was 0.9% in Tampere University Hospital. ICP frequencies differed year by year during 1969–1988. In the first three years the explanation for lower frequencies might be implementation of ICD-8, but from 1972 onwards, we suggest that frequencies fit the normal variation.

The labour register, the source of data for the principal outcome of our study, is formally structured like “an account book”, and may be considered reliable. In verifying ICP diagnoses we used paper patient records. Paper records include sources of error, as also do the present electronic patient records [Citation22]. As to laboratory results, the electronic system is probably more reliable than paper records.

It may be that we overlooked some ICP cases because of the strict inclusion criteria, i.e. symptoms of itching and abnormal laboratory tests. On the other hand, applying the strict criteria we assume that we have found the correct positive ICP cases. In ICP, pruritus is relieved in a couple of days and laboratory tests return to normal in 7–21 days after delivery. The definition of ICP also includes absence of other diseases that cause these signs. In our study, we presume that at the time of confirmation of diagnosis, that is the day of getting home from hospital, itching would be relieved and other diseases would practically be excluded. We checked systematically that none of our controls was included in the ICP group. Laboratory tests for checking ICP were not routinely undertaken for asymptomatic women.

During the 20 years of our study, diagnostics have changed to some extent. Itching has been a constant diagnostic criterion. In the early years of the era, laboratory tests, such as a thymol test, iodine test, Schles, Meulengracht, or Ehrlich, were used, but they could not be interpreted as ICP criteria for our study. Ultrasound became a common means of assessing gestational age in the 1980s, supplementing menstrual history, pregnancy test, and clinical findings. Indications for induction and Caesarean section have changed in ICP cases as well as in normal pregnancies.

Some false-positive ICP cases might be included, because itching is quite a common symptom during pregnancy, and slightly abnormal laboratory tests might occur for other reasons or without any clinical relevance. Hepatitis may also appear during pregnancy, but differential diagnosis can usually be made clinically and by additional laboratory tests. Symptomatic gallstones can raise laboratory values whereas itching is not typical of gallstones. Neither for ICP patients nor for controls did we exclude eclampsia, where hepatobiliary laboratory tests may rise, especially in HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome. We suggest that HELLP cases are not a significant group in these data.

Tampere University Hospital (TUH) deals with all normal deliveries in its area. In addition, the management of at-risk pregnancies and deliveries from a larger area is allocated to TUH. In that respect, our material is not quite equivalent to an unselected population. The university hospital selection can be seen for example in gemini frequency: in Finland, gemini frequency was 1.1% [Citation2], and in our material it was 2.1% in controls and 5.1% in ICP cases.

In our study the risk of adverse outcome in ICP pregnancies seems smaller than stated in earlier studies [Citation7,Citation13,Citation15,Citation17]. The role of primary healthcare is important in finding ICP mothers. The system for referring ICP cases from primary healthcare to specialist care was already well established in the 1970s and 1980s.

Little is known about associations of ICP with other aspects of the health of mothers and their children. It has been stated that women with a history of ICP are more prone to gallstones, and some other hepatobiliary diseases are more common in women with a history of ICP [Citation20]. In one study dyslipidemia during pregnancy was associated with ICP [Citation23]. Women with ICP have been reported to present greater glucose concentrations in serum samples collected two hours after breakfast and after supper, and in glucose tolerance tests [Citation24]. As for children, we did not observe the need for care in a neonatal unit or the neonatal death rate. Birth weights of ICP mothers’ children were lower than weights of controls. Some authors do not consider that ICP is associated with intrauterine growth retardation [Citation16,Citation25], but slightly or clearly different results have been apparent [Citation9,Citation26]. The risks of some medical and social disabilities in adulthood increased with decreasing gestational age at birth [Citation27], and further study is needed to find out if ICP increases or decreases the adverse effects of preterm birth.

Practically all (99.7%) pregnant women take advantage of public maternity healthcare in Finland [Citation2]. GPs are responsible for maternity clinics in health centres. The convention of screening itching women for ICP in primary healthcare, referring ICP patients to the obstetric clinic, and management in hospital seems to have contributed to the good outcome in Finland. Documented local guidelines for maternity care and referral instructions are essentially important for primary healthcare maternity clinics. They should be updated regularly in collaboration with GPs and obstetric clinics.

According to our findings, ICP mothers are found and taken care of appropriately, and thus ICP is only a minor risk for mother and child during pregnancy and delivery. The role of the GP is important in assessing risks in practice among women with ICP and their children.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Committee for Pirkanmaa Hospital District (R02149).

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sigurdsson J. The GP's role in maternity care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:65.

- Statistics, registers and population studies. National Institute for Health and Welfare. Finland. http://www.thl.fi/en_US/web/en/research/statistics (accessed 11 February 2010).

- Laes E, Gissler M. Health of pregnant women. Koskinen S, Aromaa A, Huttunen J, Teperi J. Health in Finland. Vammala: KTL, Stakes, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; 2006:120–1.

- Maternity and child health clinics. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. http://www.stm.fi/en/social_and_health_services/health_services/primary_health/maternity_clinics (accessed 9 March 2010).

- Reyes H. Intrahepatic cholestasis: A puzzling disorder of pregnancy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997;12:211–16.

- Lammert F, Marshall HU, Glantz A, Matern S. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. J Hepatol 2000;33:1012–21.

- Laatikainen T, Tulenheimo A. Maternal serum bile acid levels and fetal distress in cholestasis of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1984;22:91–4.

- Berg B, Helm G, Petersohn L, Tryding N. Cholestasis of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1986;65:107–13.

- Heinonen S, Kirkinen P. Pregnancy outcome with intrahepatic cholestasis. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:189–93.

- Germain AM, Carvajal JA, Glasinovic JC, Kato C S, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: An intriguing pregnancy-specific disorder. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2002;9:10–14.

- Savander M, Ropponen A, Avela K, Weerasekera N, Cormand B, Hirvioja M-L, . Genetic evidence of heterogeneity in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gut 2003;52:1025–9.

- Gonzales MC, Reyes H, Arrese M, Figueroa D, Lorca B, Andresen M, . Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in twin pregnancies. J Hepatol 1989;9:84–90.

- Glantz A, Marshall HU, Mattson LÅ. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology 2004;40:467–74.

- Davidson KM. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 1998;22:104–11.

- Fisk NM, Storey GN. Fetal outcome in obstetric cholestasis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;95:1137–43.

- Rioseco AJ, Ivancovic MB, Manzur A, Hamed F, Kato SR, Parer JT, . Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: A retrospective case-control study of perinatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170:890–5.

- Alsulyman OM, Ouzounian JG, Ames-Castro M, Goodwin TM. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Perinatal outcome associated with expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:957–60.

- Sepúlveda WH, González C, Cruz MA, Rudolph MI. Vasoconstrictive effect of bile acids on isolated human placental chorionic veins. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1991;42:211–15.

- Germain AM, Kato S, Carvajal JA, Valenzuela GJ, Valdes GL, Glasinovic JC. Bile acids increase response and expression of human myometrial oxytocin receptor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:577–82.

- Ropponen A, Sund R, Riikonen S, Ylikorkala O, Aittomäki K. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy as an indicator of liver and biliary diseases: A population based study. Hepatology 2006;43:723–8.

- Evidence-based medicine guidelines. Obstetrics. Duodecim. Finland. http://www.terveysportti.fi/ebmg/ltk.koti (accessed 8 April 2009).

- Vainiomäki S, Kuusela M, Vainiomäki P, Rautava P. The quality of electronic patient records in Finnish primary healthcare needs to be improved. Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:117–22.

- Dann AT, Kenyon AP, Wierzbicki AS, Seed PT, Shennan AH, Tribe RM. Plasma lipid profiles of women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:106–14.

- Wójcicka-Jagodzińska J, Kuczyńska-Sicińska J, Czajkowski K, Smolarczyk R. Carbohydrate metabolism in the course of intrahepatic cholestasis in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:959–64.

- Zimmermann P, Koskinen J, Vaalamo P, Ranta T. Doppler umbilical artery velocimetry in pregnancies complicated by intrahepatic cholestasis. J Perinat Med 1991;19:351–5.

- Vega J, Sáez G, Smith M, Agurto M, Morris NM. Risk factors for low birth weight and intrauterine growth retardation in Santiago, Chile (in Spanish). Rev Med Chil 1993;121:1210–19.

- Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med 2008;359:262–73.