Abstract

Cancers of the digestive organs (including the oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum and anus, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas) constitute one-fifth of all cancer cases in the Nordic countries and is a group of diseases with diverse time trends and varying consequences for public health. In this study we examine trends in relative survival in relation to the corresponding incidence and mortality rates in the Nordic countries during the period 1964–2003. Material and methods. Data were retrieved from the NORDCAN database for the period 1964 to 2003, grouped into eight 5-year periods of diagnosis. The patients were followed up until the end of 2006. Analysis comprised trends in 5-year relative survival, excess mortality and age-specific relative survival. Results. Survival following cancers of the colon and rectum has increased continuously over the observed period, yet Danish patients fall behind those in the other Nordic countries. The largest inter-country variation is seen for the rare cancers in the small intestine. There has been little increase in prognosis for patients diagnosed with cancers of the liver, gallbladder or pancreas; 5-year survival is generally below 15%. Survival also remains consistently low for patients with oesophageal cancer, while minor increases in survival are seen among stomach cancer patients in all countries except Denmark. The concomitant incidence and mortality rates of stomach cancer have steadily decreased in each Nordic country at least since 1964. Conclusion. While the site-specific variations in mortality and survival largely reflect the extent of changing and improving diagnostic and clinical practices, the incidence trends highlight the importance of risk factor modification. Alongside the ongoing clinical advances, effective primary prevention measures, including the control of alcohol and tobacco consumption as well as changing dietary pattern, will reduce the incidence and mortality burden of digestive cancers in the Nordic countries.

Cancers of the digestive organs (including the oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas) are a group of heterogeneous diseases with diverse time trends and varying consequences on public health. Together, they constitute approximately 20% of all cancers in the Nordic countries. Colon cancer is the most common, with more than 9 000 cases per year in 1999–2003 in the Nordic countries, corresponding to approximately 7% of all cancers in men and 8% in women. Cancer of the rectum ranks second and constitutes 4–5% of all cases. The other sites represent from 0.5 to 3% of the total cancer burden in the Nordic populations [Citation1].

Environmental and lifestyle factors predominate the aetiology of cancer of the digestive organs. Smoking is an established risk factor for cancers of the oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, liver, and pancreas [Citation2–4], while alcohol consumption is associated with cancers of oesophagus, colon, and liver [Citation5,Citation6]. For certain cancer sites, such as oesophagus and stomach, there are also indications of a multiplicative effect from smoking and alcohol on the cancer risk. The other main risk factor for liver cancer is infection with hepatitis B and/or C, rare conditions among the populations of the Nordic countries [Citation7]. Dietary factors have been shown to influence the risk of developing colorectal and stomach cancer, and the best established risk factor for the latter is infection with Helicobacter pylori [Citation8–10]. Low physical activity/overweight increases the risk of oesophageal, colorectal and gallbladder cancer [Citation11]. Other bowel diseases, such as Crohn's disease and colitis ulcerosa, have been shown to increase the risk of cancer of the small intestines and colon [Citation12]. Cholelithiasis is associated with gallbladder cancer and the association is correlated with stone size. Reproductive factors have also been linked to occurrence of gallbladder cancer as the disease is more common in women [Citation13].

A recent study by the EUROCARE group showed that survival from cancer in the digestive tract is highly variable in relation to the anatomical site [Citation14]. The mean European age- and area-adjusted 5-year relative survival estimates in this group of tumours were most favourable for colorectal cancer (54%). Corresponding survival figures for cancer of small intestines and stomach cancer were 42% and 25%, while survival was below 15% for oesophagus, liver, and gallbladder/biliary tract cancer. The 5-year relative survival among pancreatic cancer patients in Europe was only 6% and has been stable for a number of decades. [Citation14]

Previous Nordic studies showed that the age-standardised 5-year relative survival of oesophageal cancer patients was up to 10% (period 1958–1987) [Citation15] and below 20% among stomach cancer patients (period 1978–1992) [Citation16]. International and Nordic comparisons [Citation14,Citation17] have reported that colorectal cancer survival in Denmark fell behind the other Nordic countries and several other European populations, this despite some observed increases in survival with time. Disparities between the Nordic countries in the magnitude of relative survival ratios and the changing trends have been noted in several reports [Citation15,Citation16].

The purpose of this study is to compare the development of cancer survival in the five Nordic countries, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden in the years 1964–2003 following cancer of the digestive organs, evaluated in light of the corresponding trends in incidence and mortality.

Material and methods

The data sources and methods are described in detail elsewhere [Citation18]. In brief, the study is based on the NORDCAN database, hosting comparable data on cancer incidence and mortality in the Nordic countries delivered from the national cancer registries, with follow-up for death or emigration for each cancer patient through to the end of 2006. This study examines cancers of the oesophagus (ICD-10 C15), stomach (ICD-10 C16), small intestine (ICD-10 C17), colon (ICD-10 C18), rectum and anus (ICD-10 C19-21), liver (ICD-10 C22), gallbladder etc. (ICD-10 C23-24) and pancreas (ICD-10 C25). We calculated sex-specific 5-year relative survival for each of the diagnostic groups in NORDCAN for eight 5-year periods from 1964–1968 to 1999–2003. For the last 5-year period hybrid analysis methods were used. Country specific population mortality rates were used for calculating the expected survival. Age-standardisation used the ICSS standard cancer patient populations [Citation19]. Age-standardised incidence, mortality, and 5-year relative survival are presented, as are excess mortality rates for the follow-up periods <1 month, 1–3 months and 2–5 years following diagnosis as well as age-specific 5-year relative survival by country, sex and 5-year period.

Results

Oesophageal cancer

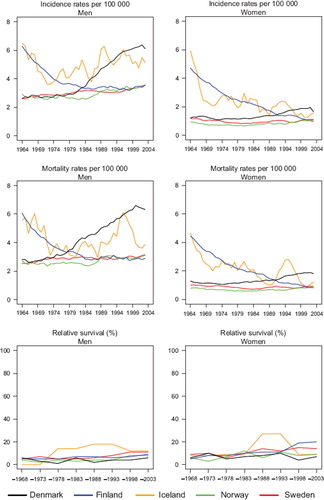

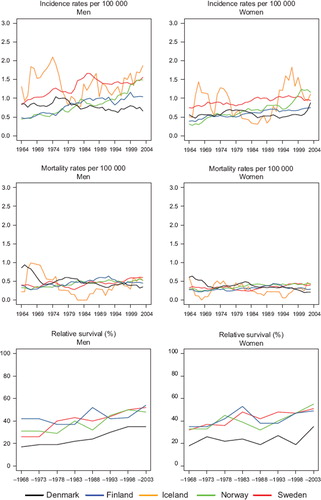

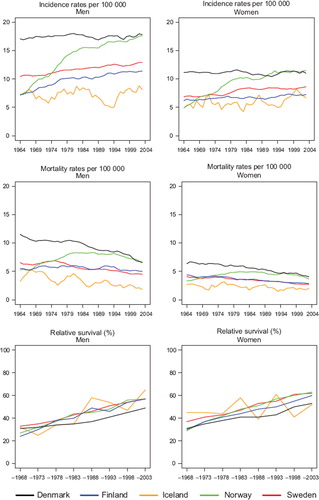

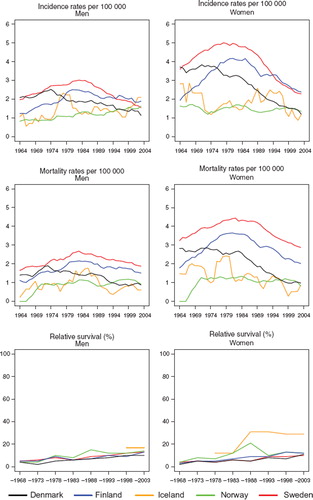

Incidence and mortality. The incidence of oesophageal cancer is higher in men than in women (). Finland had the highest incidence at the beginning of the period, but a notable decline was observed thereafter, in both sexes. The incidence in the most recent period was twice as high in Denmark compared to Finland, Norway, and Sweden, incidence in Danish males doubled since 1980, with more modest increases observed in the remaining countries. Among women, incidence increased in Denmark, but remained stable in Sweden and Norway and declined in Iceland. The trends for mortality closely followed those of incidence ().

Figure 1. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for oesophageal cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

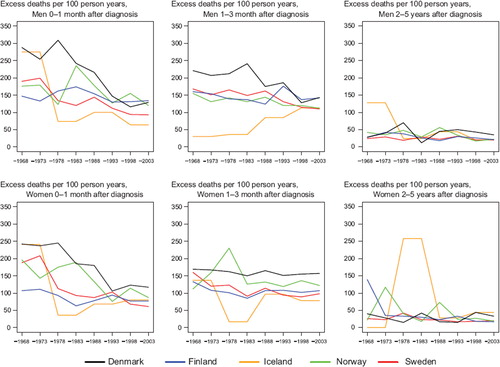

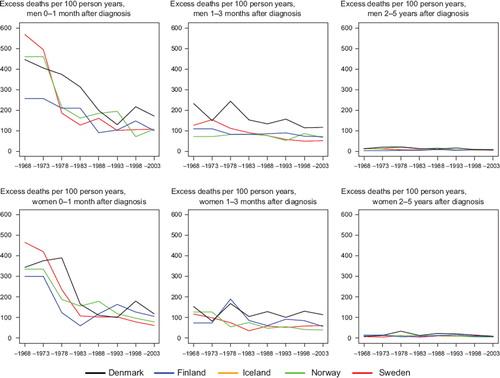

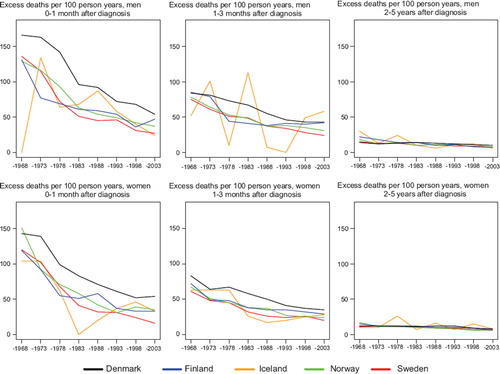

Survival. The age-standardised 5-year relative survival was at a low level throughout the observed period although it increased somewhat in more recent periods, particularly for Swedish men where it reached 11% in 1999–2003, and for Finnish and Swedish women, with ratios estimated at 20% and 14% respectively ( and ). The relative survival in Denmark has remained low at 6% in men and 7% in women diagnosed in 1999–2003. The age-specific 5-year relative survival ratios are presented in ; the general pattern that emerges is that survival declined with increasing age. Denmark tended to have the highest excess death rates over time 0–3 months after diagnosis, reached similar levels as the other countries during the 1990s among men, but remained at a high level among women (). Danish patients still had the highest rate of excess deaths in 1999–2003, 2–5 years after diagnosis.

Figure 2. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for oesophageal cancer by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table I. Trends in survival for oesophageal cancer by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table II. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after oesophageal cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Stomach cancer

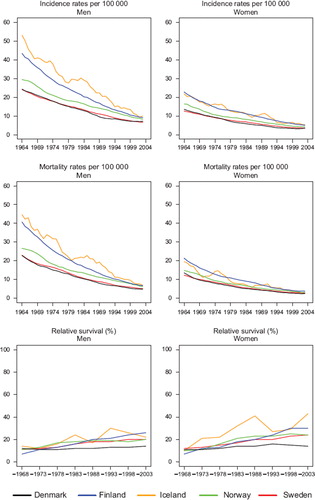

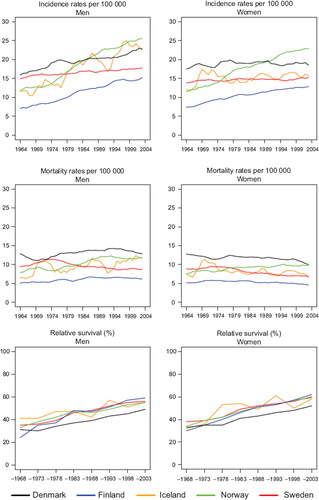

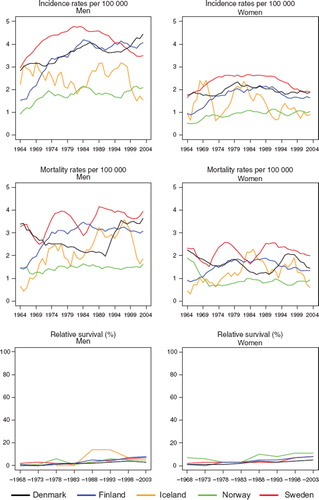

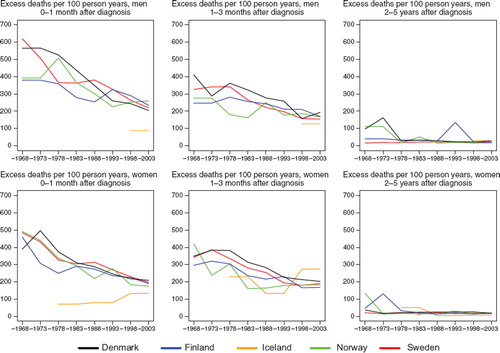

Incidence and mortality. Age-standardised incidence and mortality rates of stomach cancer have declined steadily in each of the Nordic countries during the four decades studied, irrespective of sex (). In absolute terms, the largest reductions (in both incidence and mortality) were seen among men in Finland and Iceland, but the decline among Norwegian men appeared less steep relative to the other populations. A progressive convergence in these rates was seen with time, with a 1.5-fold variation between countries in incidence and mortality circa 2003, with the highest sex-specific rates in Finland and Iceland, and lowest in Sweden and Denmark. The incidence rate in the Nordic countries was around eight per 100 000 in men and four in women; mortality was slightly lower at almost six and three per 100 000, respectively.

Figure 3. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for stomach cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

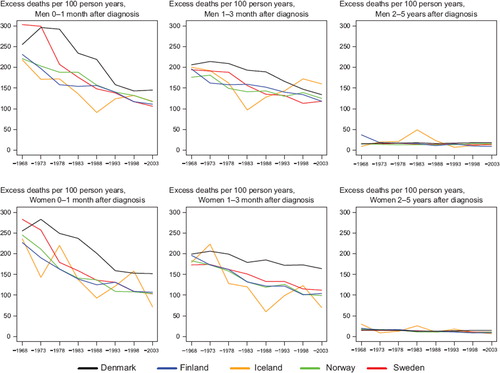

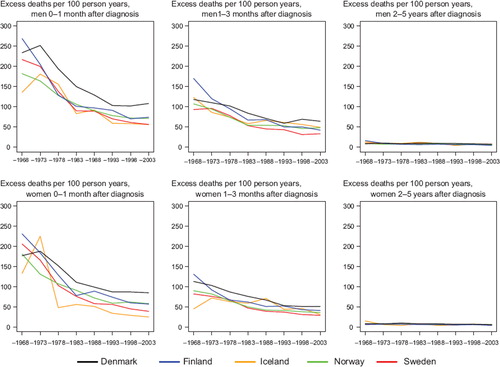

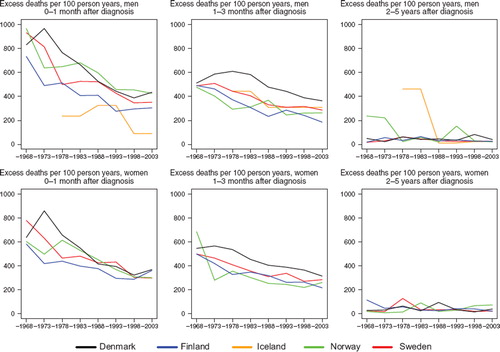

Survival. For patients diagnosed 1969–1973 in the Nordic countries, age-standardised 5-year relative survival varied from around 10 to 15% compared with a wider range, 15 to 30%, in the latest diagnostic period (). Varying increases in 5-year survival were observed over time in Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Finland showed the greatest rise in survival in absolute terms over the 40-year period, with the relative survival of 7% for both sexes in the period 1964–1968 increasing to 26% and 30% for men and women diagnosed between 1999 and 2003. Survival was lower in Denmark and increase in survival over time appeared quite modest or non-existent (). Lower survival ratios in Denmark were seen for all ages () and appeared to be related to a relatively poorer prognosis of patients within the first year after diagnosis (data partially shown, ). Only minor variation in excess death rates between the Nordic populations was observed 2–5 years after initial diagnosis.

Figure 4. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for stomach cancer by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table III. Trends in survival for stomach cancer by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table IV. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after stomach cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Cancer of small intestine

Incidence and mortality. Cancer of the small intestine is rare with an age-standardised rate of 0.6–1.7 per 100 000 in 1999–2003. It increased slightly in Sweden, Norway, and Finland over calendar time, with a higher increase among men than women. The incidence in Sweden was double that of Finland and Norway circa 1964 but a steep and continuing increase in Norway from circa 1994 has placed Norway at the top. In 1964 the incidence in Denmark was at the same level as in Sweden, or a bit lower (women), but the Danish incidence remained stable (women) or slightly declining (men). Only a marginal increase in mortality was seen with hardly any difference between countries (). Overall, the relative magnitude of rates is more homogenous across countries for mortality than for incidence.

Figure 5. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for cancer of small intestine by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Survival. Survival was at similar levels and increased in Finland, Norway and Sweden from about 35% in 1964–1968 to 50–55% in 1999–2003, while the Danish survival was at a lower level, beginning at around 18% and reaching 35%, nearly 15 to 20 percent units below the other countries for patients diagnosed with small intestinal cancer 1999–2003 (). The excess mortality in the first month after diagnosis steeply decreased up until 1980 in all countries except Finland (men), which had lower excess death rates than the other countries from the 1960s (). For excess mortality 1–3 months after diagnosis the trend was rather stable albeit at a higher level in Denmark than in the other countries. From 2–5 years after diagnosis there have not been any changes to the excess mortality figures; all countries are at a very low level. Due to small numbers it is challenging to draw any conclusions regarding the age-specific 5-year relative survival, but the general pattern is that it increases with time but decreases with age ().

Figure 6. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for cancer of small intestine by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003. No Icelandic curves. Too few patients to calculate survival for Iceland.

Table V. Trends in survival for cancer of small intestine by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table VI. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after cancer of small intestine by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Colon cancer

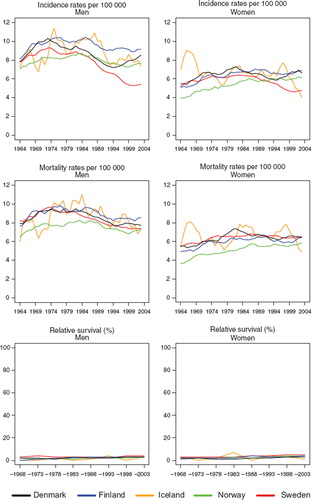

Incidence and mortality. The incidence of colon cancer has been increasing among men in the Nordic countries, most notably in Norway (). Whereas male incidence rates in Denmark were historically the highest, rates in Norway and Iceland surpassed them in the 1980s. Among Norwegian and Finnish women, colon cancer incidence increased in parallel to that in men, whilst the incidence among Danish, Icelandic and Swedish women remained stable. Colon cancer mortality, on the other hand, declined but remained highest among Danish men, increased to some extent in Norway and Iceland, decreased in Sweden, and remained stable in Finland. Rates in women shared similar temporal patterns, particularly in the last two decades under study.

Figure 7. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for colon cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Survival. The age-standardised 5-year relative survival increased in the observed period for all Nordic countries and in both sexes ( and ), and ranged from 50 to 60% in 1999–2003. Throughout the period from 1969 to 2003 the Danish survival was lower than in the other Nordic countries. Finland had the lowest survival among the Nordic countries in 1964–1968 but as a result of rapid survival increases observed thereafter, Finnish patients had the highest survival in both sexes in 1999–2003. The fluctuation of the Icelandic survival curve was due to the small population size, but the survival trends were fairly similar to those seen in Sweden, Finland and Norway. Studying the excess deaths by time since diagnosis, the rates were higher among Danish men and women within the first three months after diagnosis, although in all countries excess mortality was halved over the four decades. Beyond two years after diagnosis the excess mortality was similar in all Nordic countries ().

Figure 8. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for colon cancer by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table VII. Trends in survival for colon cancer by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

The age-specific 5-year relative survival ratios are presented in . The general pattern was that survival diminished with increasing age, but increased with time in each age group, with the largest increases in survival seen in patients above the age of 70 at diagnosis. From the late-1960s survival among Danish men and women fell behind the other Nordic countries in all patients diagnosed at ages under 90.

Table VIII. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after colon cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Rectal and anal cancer

Incidence and mortality. The incidence of rectal cancer in Denmark was historically the highest among the Nordic countries and was rather constant during the whole period with an incidence among men of 17 and among women 11 per 100 000. Norway started at a relatively low level of around five per 100 000 in 1964, close to those of Iceland, Finland, and Swedish women, while Swedish men had a slightly higher baseline incidence at 11 per 100 000. Norwegian incidence increased steeply to a similar level of that observed in Denmark (), while a less rapid increase was observed for Finland and Sweden. The mortality has been decreasing during the whole period at almost the same pace in all countries, except in Norway, where the mortality increased up until the mid-1980s.

Figure 9. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for rectal and anal cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Survival. Rectal cancer survival increased steadily throughout the observation period. Since the early 1970s there was little difference in relative survival between men in Finland, Norway and Sweden, while Finnish women had a slightly poorer survival than Norwegian and Swedish patients. Survival in Denmark was comparable to the other Nordic countries circa 1964, but subsequently Danish survival did not increase to the same extent as in the other populations. Five-year relative survival after rectal cancer in the Nordic populations varied between 49% and 65% in 1999–2003 and the absolute increases in 5-year survival were between 18 and 34 percent units over the diagnostic period 1964 to 2003 (lower for Icelandic women) ().

Table IX. Trends in survival for rectal and anal cancer by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

In , the curves of excess mortality for different follow-up intervals show that the decrease was most evident within the first month after diagnosis from a level above 100 deaths per 100 person years, and that excess mortality halved over time. The reduction in excess mortality over time continued for the next follow-up intervals until two years after diagnosis (data not shown for three months to two years). For follow-up 2–5 years after diagnosis, the excess rates were stable and at about the same level, at less than 10 excess deaths per 100 person years in all Nordic countries. Age-specific 5-year relative survival increased in successive calendar periods, but was consistently lower for patients aged over 70 years at diagnosis in all countries for both sexes ().

Figure 10. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for rectal and anal cancer by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table X. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after rectal and anal cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Liver cancer

Incidence and mortality. Incidence trends in liver cancer by country followed a similar pattern among men and women, although the incidence among women was consistently about half that of men (). An initial increase in incidence was observed for both sexes in Finland and Sweden between 1960 and 1980, followed by a decrease, most notably in Sweden. The age-standardised incidence varied 2-fold between the countries with the highest incidence in Sweden and lowest in Norway. The liver cancer mortality pattern between countries and over time was largely similar to incidence, but with larger trend shifts during the observed period, especially in Sweden and Denmark.

Figure 11. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for liver cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Survival. Survival for persons diagnosed with liver cancer was low, and increases over the diagnostic period were quite modest, with the highest 5-year relative survival approaching 11% for Norwegian female patients, while Denmark had the lowest survival, 3% in males and 5% in females in 1999–2003 ( and ). The excess mortality declined during the first month after diagnosis from about 800 (men) and 600 (women) deaths per 100 person years to 400 in 1999–2003. Excess mortality 1–3 months after diagnosis also declined, with the highest level in Denmark. In the follow-up period 2–5 years after diagnosis, no systematic variation over time and between the countries was seen (). Persons diagnosed with liver cancer before the age of 50 tended to have a higher survival than older persons, while women tended to have a higher survival than men ().

Figure 12. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for liver cancer by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table XI. Trends in survival for liver cancer by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table XII. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after liver cancer by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Cancer of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary ducts

Incidence and mortality. Historically cancer of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary ducts (“gallbladder”) was more common in women than in men in the Nordic countries, but in recent years the incidence rates did not differ markedly. Variation between countries was larger among women (range 1.2–2.5 per 100 000) than men (1.4–1.9). In Finland and Sweden incidence peaked around 1980 and declined afterwards, while in Denmark decrease started in the mid-1970s. Norway and Iceland had the lowest incidence, slightly increasing over time for men and stable among women (). In general, mortality trends followed the incidence patterns, although mortality was higher than incidence in Sweden from the mid-1990s ().

Figure 13. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for cancer of the gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary ducts by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Survival. Survival was rather low for gallbladder cancer patients, but increased slightly over time. Five-year relative survival in 1999–2003 variedfrom 10 to 14% in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. Norwegian female patients, and to some extent male patients, had increased survival during the 1980s, although the survival ratios appeared to decline to the same level as the other countries thereafter. Patients in Denmark and Sweden had the largest reduction in excess mortality over time within the first month after diagnosis, as well as during the interval 1 to 3 months, particularly among males. Excess mortality differed more substantially between the countries in the 1960s than in the most recent period, but the contemporary mortality levels were higher at approximately 200 deaths per 100 person years in women in the first three months after diagnosis for the period 1999–2003. The corresponding male figures were 150–250 per 100 person years ().

Figure 14. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for cancer of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bilary ducts by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Studying age-specific relative survival revealed that the younger patients, aged below 50 years, had higher and increasing survival, especially among women. The 5-year relative survival proportion was however only 30% and 29% in Iceland and Denmark, respectively, the countries with the highest survival, and was lowest in Sweden at 16% ().

Table XIII. Trends in survival for cancer of gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary ducts by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table XIV. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after cancer of gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary ducts by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Cancer of pancreas

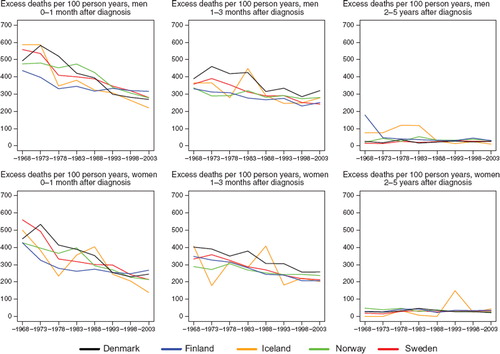

Incidence and mortality. The incidence of pancreatic cancer was higher among males than females through most of the observed period. For males, there was an increasing trend until the early-1970s, when incidence reached a plateau of around 9–10 per 100 000, before starting to decline from the mid-1980s. Up to the mid-1980s the incidence was lower in Norway and Sweden, followed by a more pronounced decrease in Sweden than in the other countries. In each of the Nordic countries the trend either stabilised or increased again from the mid-1990s, with the most pronounced increase observed in Denmark. The unstable Icelandic incidence rates reflect the small population but follow the general pattern of the Nordic countries (). In general, the mortality rates closely followed those of incidence, although in Sweden the number of pancreatic cancer deaths exceeded the number of incident cases.

Figure 15. Trends in age-standardised (World) incidence and mortality rates per 100 000 and age-standardised (ICSS) 5-year relative survival for cancer of pancreas by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Survival. There has been little change in survival for patients diagnosed with pancreas cancer over the consecutive diagnostic periods (), with 5-year survival quite stable at around 3–5% (compared to 0–3% in the 1960s), with little variation between the countries (). However, some declines in excess mortality were noted in the first three months after diagnosis. The excess mortality was highest in Denmark in the follow-up interval 1–3 months. The excess mortality rates were low and reasonably stable over time and between countries 2–5 years after diagnosis ().

Figure 16. Trends in age-standardised (ICSS) excess death rates per 100 person years for cancer of pancreas by sex, country, and time since diagnosis. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table XV. Trends in survival for cancer of pancreas by sex and country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Table XVI. Trends in 5-year age-specific relative survival in percent after cancer of pancreas by sex and country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Discussion

The patient survival trends following the diagnoses of cancer of the digestive organs are subject to large variation according to both tumour sites and study population. A general pattern that emerged was a poorer survival among Danish patients than in the other Nordic countries, in terms of 5-year relative survival as well as excess mortality, with the latter particularly apparent within the first months after diagnosis. Large fluctuations in the Icelandic curves reflect the inherent random variation due to the small Icelandic population size.

Cancers of the oesophagus consist mainly of two subgroups of tumour types, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. The former is mainly associated with obesity, while squamous cell carcinoma is strongly associated with smoking and alcohol consumption [Citation20]. The 2-fold increase in incidence among Danish men stemmed from increase in both types, while in Sweden a decrease in squamous cell carcinoma was accompanied by an equally large increase of adenocarcinoma [Citation21,Citation22]. Apart from being strong risk factors, alcohol and tobacco consumption may also influence the prognosis of patients with respect to their capacity to endure treatment [Citation23]. As in other European countries the Nordic survival of patients with oesophageal cancer is rather poor with no large differences between the countries and only very modest improvements over time.

In contrast to the steady declines in stomach cancer incidence and mortality rates in the Nordic countries in the last 40 years, variations in the extent of more recent increases in 5-year relative survival have led to a 2-fold variability in prognosis at the beginning of the millennium. Stomach cancers are histologically heterogeneous cancers [Citation24] that include two major histologic subtypes, intestinal and diffuse adenocarcinoma. In several European population-based studies [Citation25–27], histological type has been revealed as an independent determinant of stomach cancer survival. The constant declines in incidence and mortality are similar in the Nordic countries and are considered part of the “unplanned triumph” of primary prevention of intestinal-type stomach cancer [Citation28], a near-universal phenomenon possibly mediated through the introduction of refrigerators for preserving food and/or treatment of infection with Helicobacter pylori [Citation10] thus not isolated to the Nordic populations. The variability in the Nordic survival trends and survival estimates, however, largely pertains to disparities in the ability to reduce case fatality among the respective patient populations.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to be important in stomach cancer survival. However, the excess mortality among Danish patients occurred within the first 12 months of diagnosis, implying that there exists a critical window for early intervention. As observed for other common neoplasms, one might conjecture that Danish patients are on average, diagnosed at a later stage than their Nordic counterparts, leading to a poorer 5-year survival. Consistent with this is a EUROCARE study which suggested that stage at presentation may partially explain survival differences among 17 European populations [Citation29]. One may speculate that other factors such as improving perioperative care (e.g. better surgery and lower perioperative mortality) in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiochemotherapy may also contribute [Citation30,Citation31]. Verdecchia et al. suggested that the modest improvements seen in survival of stomach cancer could be explained by a heterogenous decrease in incidence, with a reduction of only the less aggressive cancers while the incidence of the more aggressive remains stable [Citation32].

The survival among Danish colon, rectum and small intestine cancer patients was inferior to patients in the other Nordic countries. The discrepancy between countries was most notable for cancer of the small intestine which mainly consists of two histologic types, carcinoids and adenocarcinoma, often found in different sub-locations and with different prognosis [Citation12]. A Swedish study showed a 5-year relative survival of nearly 70% in the group with carcinoid tumours, which have had a substantial progress over the past four decades, while it was only around 20% in the adenocarcinoma group [Citation33]. However, the number of cases under study in each country is small and estimates thus uncertain. Based on a comparison between Sweden and Denmark there is no indication that the histological distribution could explain the poorer survival in Denmark (data not shown). Diffuse symptoms result in delayed diagnosis and tumours commonly diagnosed at advanced stages, limiting the possibility of curative treatment. This may thus explain the poorer survival among patients with cancer of small intestine in general [Citation34].

A recent EUROCARE study of colon cancer patients diagnosed 1988 to 1999 showed that the magnitude of survival increases in the Nordic countries was in line with what was observed in other European countries, although improvements in prognosis generally were higher in women than men [Citation32]. The survival among Danish patients has been inferior throughout the study period, and any effects from changes in patient management and care as a result of the changes prior to and after the first Danish Cancer Control plan introduced in year 2000 cannot yet be demonstrated for colon cancer. Patient management as well as the health care system's ability to provide endoscopic investigation has been suggested to influence the survival [Citation35]. During the study period, colon and rectum cancer surgery in Denmark was carried out at many hospitals and only after the end of this study a process of centralisation into fewer units begun [Citation36].

The Nordic trends in incidence and mortality of rectal cancer are in line with those in other European countries [Citation35] and Nordic prognosis is quite good, with the relative survival higher than the European average, with the exception of Denmark [Citation14]. The recently published article by Verdecchia et al. [Citation32] shows that progress in the Nordic countries is smaller among women than men but generally in line with the European average.

Rectal cancer is an example where substantial progress has been achieved within the limitations of existing therapeutic principles via improved local tumour control. The determinants include improvement of surgical technique, total mesorectal excision (TME), preoperative radiation, and a concentration of operations on fewer surgeons with better training [Citation37–40]. Fewer repeat operations after initial surgery are needed in recent years due to the improved skills of surgeons, which in turn results in fewer complications and better prognosis [Citation41]. The sharp decline in excess mortality during the first few months after diagnosis is likely due to this, in combination with more patients receiving an early diagnosis.

Pilot projects of screening for colorectal cancer have taken place in the last decade in several of the Nordic countries, but it is too early to expect influence on the trends in incidence and survival [Citation17]. A high resolution study of rectum adenocarcinoma in the Nordic countries in 1997 with data from Norway, Sweden and Denmark based on the national clinical rectal registers showed that Dukes stage was less favourable in Denmark at diagnosis and that preoperative radiation seldom was used, but that a lower survival still persisted in Denmark when adjusting for stage [Citation42]. As a comparison, approximately 50% of the patients in Sweden now receive preoperative radiotherapy [Citation43], and rectal surgery is concentrated to fewer units throughout the country.

The improvement in patient survival after cancers of the liver, “gallbladder”, or pancreas is very minor in all the Nordic countries, although some advances are noted for liver and “gallbladder” during the last decade. For liver cancer this can probably be explained by improved imaging techniques and early diagnosis in combination with advances in surgical techniques and postoperative care [Citation44] and the reduction in excess mortality during the first month after diagnosis supports this. We found that young patients have a better survival than older patients, although liver cancer is a rare disease before the age of 50. The sudden shifts observed in the liver cancer mortality trends in Denmark and Sweden are likely explained by changes in coding practices (e.g. inclusion of unspecified liver cancers), and autopsy rates particularly in Sweden, not including cases based on death certificates alone.

Survival from cancer in the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts is very poor, although a positive development is that incidence appears to be declining. A study in Scotland showed that declining incidence may be related to an increase in cholecystectomy rate, but no firm conclusions were drawn [Citation45]. There are often no early symptoms of cancer in the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts, and consequently many of them are not diagnosed until the tumour is at an advanced stage, which highly influences outcome. The large variation in survival between European countries in the EUROCARE-4 [Citation14] study most likely relates to small numbers and large variations in tumour stage at diagnosis. Surgery is the primary treatment but this is not always feasible, and as these tumours are not very sensitive to radiation or chemotherapy, cancer care is often palliative. The reduction in excess mortality in the Nordic countries during the first month after diagnosis indicates that life after a gallbladder cancer diagnosis has been prolonged to some extent over the last few decades, but without an early diagnosis, prognosis remains rather poor.

There has been little progress in the prognosis of the pancreatic cancer patients since the 1960s, and this is in line with the lack of significant medical advances in early detection and treatment [Citation35,Citation46]. Incidence and mortality rates of pancreatic cancer generally follow each other closely, although in Sweden the number of deaths from cancer of pancreas (and gallbladder) exceeds the number of incident cases since around 1990. The discrepancy has increased in recent years and is also seen in Denmark. Autopsy rates are low in both countries and this might cause an excess reporting of pancreatic cancer as the underlying cause of death in death certificates [Citation47]. The cancer registry in Sweden does not register cases based on death certificate as the only source.

Pancreatic cancer lacks early symptoms and is, as a consequence, often diagnosed at a late stage when disease has spread to neighbouring tissues, beyond the treatment window of curative resection. The inaccessibility of the pancreas further limits the possibility of surgical removal. The aggressive nature of the tumour leads to a rapid progression that has strong resistance to chemotherapy [Citation46]. Only 10–20% of the cases are operable, which is the only potential cure, and this can be combined with radiotherapy and/or adjuvant chemotherapy. It was reported that such patients experience a better prognosis: about 20% of them survive for five years [Citation2], but a review of long-term survivors from pancreatic cancer in the Finnish cancer registry revealed that most of them were incorrectly diagnosed with a pancreas cancer which indicates that survival actually might be even lower [Citation48]. It has been suggested that the modest improvements in 1-year survival in Norway may reflect more aggressive use of surgery and chemotherapy [Citation49].

Recent randomised trials have not delivered the improved results hoped for; the improvement in survival is small and the additional costs – both in financial terms as well as the risk of toxicity for patients from combination treatment – have been questioned [Citation46]. Meanwhile, the aetiology of pancreatic cancer is not fully understood. Smoking is acknowledged as a risk factor although not all cases are attributable to tobacco. Thus primary prevention aimed at smoking avoidance and cessation, would lead to reduction of incidence but the magnitude of this is unclear. Chua et al. [Citation46] suggested that future research should focus on the biology of the disease at a cellular, molecular and genetic level which might lead to an understanding of both tumour progression and reasons for host resistance to treatment. In addition to this, identifying molecular markers which might be prognostic for outcome could, in the future, help clinicians tailor treatment to each patient. Karim-Kos et al. [Citation35] suggests centralisation of surgery as a possible way to improve survival, which so clearly is demonstrated for rectal cancer [Citation38–40].

Alcohol and tobacco consumption are important risk factors for several cancer sites in the digestive tract and may also have an effect on co-morbidity for these patients. This, as well as other environmental and lifestyle factors, plays a predominant role in the development and prognosis of patients with cancer in the digestive organs, and poses a challenge for future public health in the Nordic countries.

Acknowledgements

The Nordic Cancer Union (NCU) has financially supported the development of the NORDCAN database and program, as well as the survival analyses in this project.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, Bray F, Klint Å, Olafsdottir E, . NORDCAN: Cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence in the Nordic countries. Version 3.3. Association of Nordic Cancer Registries, Danish Cancer Society. 2008. Available from: www.ancr.nu.

- Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2004;363:1049–57.

- Thun MJ, Henley SJ. Tobacco. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 217–42.

- Dreyer L, Winther JF, Pukkala E, Andersen A. Avoidable cancers in the Nordic countries. Tobacco smoking. APMIS Suppl 1997;76:9–47.

- Marshall JR, Freudenheim J. Alcohol. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 243–58.

- Dreyer L, Winther JF, Andersen A, Pukkala E. Avoidable cancers in the Nordic countries. Alcohol consumption. APMIS Suppl 1997;76:48–67.

- London WT, McGlynn KA. Liver Cancer. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 763–86.

- Willet WC. Diet and nutrition. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 405–21.

- Shibata A, Parsonnet J. Stomach cancer. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 707–20.

- Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: A global perspective. Washington DC: World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007.

- Lee I-M, Oguma Y. Physical activity. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 449–67.

- Beebe-Dimmer JL, Schottenfeld D. Cancers of the small intestine. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 801–8.

- Hsing AW, Rashid A, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF Jr. Biliary tract cancer. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 787–800.

- Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn A, Marchesi F, Capocaccia R. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995–1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:931–91.

- Engeland A, Haldorsen T, Tretli S, Hakulinen T, Hörte LG, Luostarinen T, . Prediction of cancer mortality in the Nordic countries up to the years 2000 and 2010, on the basis of relative survival analysis. A collaborative study of the five Nordic Cancer Registries. APMIS Suppl 1995;49:1–161.

- Engeland A, Haldorsen T, Dickman PW, Hakulinen T, Möller TR, Storm HH, . Relative survival of cancer patients—a comparison between Denmark and the other Nordic countries. Acta Oncol 1998;37:49–59.

- Engholm G, Kejs AM, Brewster DH, Gaard M, Holmberg L, Hartley R, . Colorectal cancer survival in the Nordic countries and the United Kingdom: Excess mortality risk analysis of 5 year relative period survival in the period 1999 to 2000. Int J Cancer 2007;121:1115–22.

- Engholm G, Gislum M, Bray F, Hakulinen T. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with cancer in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Material and methods. Acta Oncol 2010.

- Corazziari I, Quinn M, Capocaccia R. Standard cancer patient population for age standardising survival ratios. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2307–16.

- Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni JF Jr. Esophageal cancer. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 697–706.

- Falk J, Carstens H, Lundell L, Albertsson M. Incidence of carcinoma of the eosophagus and gastric cardia. Changes over time and geographical differences. Acta Oncol 2007;46:1070–4.

- Stockeld D, Backman L, Fagerberg J, Granström L. Esophageal cancer in Stockholm county 1978–95. Acta Oncol 2007;46:1075–84.

- Tønnesen H, Nielsen PR, Lauritzen JB, Møller AM. Smoking and alcohol intervention before surgery: Evidence for best practice. Br J Anaesth 2009;102:297–306.

- Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. APMIS 1965;64:31–49.

- Nikulasson S, Hallgrimsson J, Tulinius H, Sigvaldason H, Olafsdottir G. Tumours in Iceland. 16. Malignant tumours of the stomach. Histological classification and description of epidemiological changes in a high-risk population during 30 years. APMIS 1992;100:930–41.

- Pinheiro PS, van der Heijden LH, Coebergh JW. Unchanged survival of gastric cancer in the southeastern Netherlands since 1982: Result of differential trends in incidence according to Lauren type and subsite. Int J Cancer 1999;84:28–32.

- Verdecchia A, Corazziari I, Gatta G, Lisi D, Faivre J, Forman D. Explaining gastric cancer survival differences among European countries. Int J Cancer 2004;109:737–41.

- Howson CP, Hiyama T, Wynder EL. The decline in gastric cancer: Epidemiology of an unplanned triumph. Epidemiol Rev 1986;8:1–27.

- Faivre J, Forman D, Esteve J, Gatta G. Survival of patients with oesophageal and gastric cancers in Europe. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur J Cancer 1998;34:2167–75.

- De Vita F, Giuliani F, Galizia G, Belli C, Aurilio G, Santabarbara G, . Neo-adjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy of gastric cancer. Ann Oncol 2007;18(Suppl 6): vi120–3.

- Foukakis T, Lundell L, Gubanski M, Lind PA. Advances in the treatment of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Acta Oncol 2007;46:277–85.

- Verdecchia A, Guzzinati S, Francisci S, De Angelis R, Bray F, Allemani C, . Survival trends in European cancer patients diagnosed from 1988 to 1999. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1042–66.

- Talbäck M, Stenbeck M, Rosén M. Up-to-date long- term survival of cancer patients: An evaluation of period analysis on Swedish Cancer Registry data. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:1361–72.

- Singhal N, Singhal D. Adjuvant chemotherapy for small intestine adenocarcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;3:CD005202.

- Karim-Kos HE, de Vries E, Soerjomataram I, Lemmens V, Siesling S, Coebergh JW. Recent trends of cancer in Europe: A combined approach of incidence, survival and mortality for 17 cancer sites since the 1990s. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1345–89.

- Harling H, Bülow S, Møller LN, Jørgensen T. Hospital volume and outcome of rectal cancer surgery in Denmark 1994–99. Colorectal Dis 2005;7:90–5.

- Dickman PW, Adami HO. Interpreting trends in cancer patient survival. J Intern Med 2006;260:103–17.

- Dahlberg M, Glimelius B, Påhlman L. Changing strategy for rectal cancer is associated with improved outcome. Br J Surg 1999;86:379–84.

- Martling A, Cedermark B, Johansson H, Rutqvist LE, Holm T. The surgeon as a progonostic factor after the introduction of total mesorectal excision in the treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2002;89:1008–13.

- Wibe A, Møller B, Norstein J, Carlsen E, Wiig JN, . A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer—implemetation of total mesorectal excision as a routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:857–66.

- Wibe A, Carlsen E, Dahl O, Tveit KM, Weedon-Fekjaer H, Hestvik UE, . Nationwide quality assurance of rectal cancer treatment. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:224–9.

- Folkesson J, Engholm G, Ehrnrooth E, Kejs AM, Pahlman L, Harling H, . Rectal cancer survival in the Nordic countries and Scotland. Int J Cancer 2009;125:2406–12.

- National Guidelines for treatment of colon- and rectal cancer. Stockholm, Sweden: National Board of Health and Welfare; 2007.

- Hussain SA, Ferry DR, El-Gazzaz G, Mirza DF, James ND, McMaster P, . Hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2001;12:161–72.

- Wood R, Fraser LA, Brewster DH, Garden OJ. Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer and trends in cholecystectomy rates in Scotland, 1968–1998. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:2080–6.

- Chua YJ, Zalcberg JR. Pancreatic cancer—is the wall crumbling? Ann Oncol 2008;19:1224–30.

- Nagenthiraja K, Ewertz M, Engholm G, Storm HH. Incidence and mortality of pancreatic cancer in the Nordic countries 1971–2000. Acta Oncol 2007;46:1064–9.

- Carpelan-Holmström M, Nordling S, Pukkala E, Sankila R, Lüttges J, Klöppel G, . Does anyone survive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma? A nationwide study re-evaluating the data of the Finnish Cancer Registry. Gut 2005;54:385–7.

- Søreide K, Aagnes B, Møller B, Westgaard A, Bray F. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer in Norway: Trends in incidence, basis of diagnosis and survival 1965–2007. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010;45:82–92.