Abstract

Aims. To develop a questionnaire for cancer patients’ informal caregivers, measuring the caregiving tasks and consequences, and the caregivers’ needs with a main focus on the interaction with the health care professionals. Such an instrument is needed to evaluate the efforts directed towards caregivers in the health care system. Material and methods. In order to identify themes relevant for the questionnaire, existing literature was reviewed and supplemented with focus group interviews with cancer patients’ caregivers, cancer patients, clinicians, and cancer counselors. For each of the identified themes, one or more items were developed. During the development process, the items were evaluated by cognitive interviews in order to reduce problems with comprehension and response. Results. The literature review and eight focus group interviews with a total of 39 participants resulted in a list of relevant themes concerning the caregiving tasks and consequences, and the caregivers’ needs. Subsequently, items were developed, covering each relevant theme, and the questionnaire draft was evaluated by cognitive interviews with 24 caregivers. All in all, eight versions of the full questionnaire were evaluated, and furthermore, two items in the final version were evaluated in eight additional interviews. The final version of the questionnaire, called the Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs Questionnaire (CaTCoN), contains 41 items. Conclusion. The CaTCoN aims to measure the extent of cancer caregiving tasks and consequences, and the caregivers’ needs, mainly concerning information from and communication and contact with the health care professionals. The psychometric properties of the instrument need to be evaluated before the CaTCoN is ready for use.

The primary focus of the health care system is to treat and provide care to the patients. However, when a life-threatening disease such as cancer is diagnosed, the patient's informal caregivers (i.e. a spouse, the closest family, close friends, etc.) are also involved in and affected by the patient's disease, and 10–50% of the caregivers experience considerable strain [Citation1,Citation2]. Studies have shown that caregivers often undertake a range of disease related tasks, e.g. treatment monitoring [Citation3–5], symptom management [Citation4,Citation5], physical care [Citation3,Citation4,Citation6,Citation7] and emotional support [Citation5]. Often, caregivers also take over most of the everyday tasks such as housekeeping [Citation3,Citation4,Citation6], cooking [Citation8], child care [Citation8] etc., as the patient may become unable to carry out these tasks [Citation5]. Caregivers may experience negative consequences of caregving such as distress [Citation6,Citation9–12], depression [Citation3–5,Citation7,Citation9–13], anxiety [Citation3–7,Citation10–14], fatigue [Citation5–7,Citation11,Citation13,Citation14] and insomnia [Citation4–7,Citation11,Citation13], and these consequences may not only affect the caregiver, but also the patient [Citation15]. Yet, some positive consequences of caregiving are also described, e.g. post-traumatic growth and improved sense of self-worth [Citation9].

While providing care, caregivers may experience various needs, including need for help with the physical care of the patient [Citation3], need for information regarding the disease course, treatment, symptoms etc. [Citation5], need for information about emotional distress [Citation5], need for support to one self from the health care professionals [Citation16], etc. Thus, the health care professionals can play a major role for the caregivers’ perception of the situation by informing and supporting the caregivers.

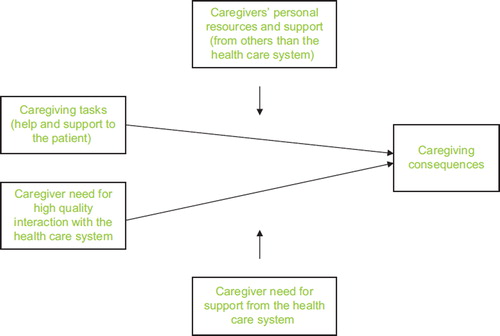

The research carried out to date has employed theoretical frameworks to a variable extent. One way of understanding the connection between caregivers’ involvement and the negative consequences, they may experience, is by applying Lazarus and Folkman's stress-coping theory [Citation17], which is a theoretical framework often used in caregiving research. According to the theory, the caregiving tasks will be perceived as stressful and difficult to cope with if the caregiver's resources, such as sociodemographic background, personal traits, physical well being and social support, are inadequate. If the resources for coping are insufficient, the result will be negative consequences for the caregiver.

The presented knowledge about caregiving tasks and consequences, and the caregivers’ needs combined with the stress-coping theory constitute the conceptual framework for this study (). Within this framework, caregivers help and support the patient and can in connection to the caregiving tasks experience needs regarding the interaction with the health care system, e.g. information from the health care professionals. The caregiving tasks may result in positive (psychological or social) consequences for the caregivers. However, if the personal resources or the resources provided by the health care system are inadequate, it may have negative (physical, psychological, social or financial) consequences for the caregiver. Given the documented importance of the interaction with the health care system and the resulting requirement of insight into the sufficiency of this interaction (in order to make it function optimally), the focus within the described framework is the needs that relate to the contact with the health care professionals.

The presence of different tasks, consequences and needs among cancer patients’ caregivers is documented in international studies, but we only have limited knowledge about Danish caregivers’ situation. According to a study of Danish cancer patients, patients often consider the hospital conditions for their caregivers far from optimal [Citation18]. However, no Danish surveys have investigated the caregivers’ own perception of their situation.

In order to improve the conditions for caregivers, we need to know the caregivers’ perception of tasks, consequences and needs. To elucidate this, a large survey, studying two research questions, was planned in Denmark:

How do caregivers experience being a caregiver of a cancer patient, and which needs do they have during the course of the disease? i.e. which tasks do the caregivers face, which positive and negative consequences do they experience, and in continuation of this, which needs do the caregivers have?

To what extent do the caregivers experience that the health care professionals involve and support them in a way that meets their needs? i.e. how are the caregivers’ needs regarding the interaction with the health care professionals met?

In order to measure the caregivers’ perception of tasks, consequences and needs, we searched for an existing questionnaire measuring all of the aspects of being a caregiver included in the two research questions. A large number of questionnaires for caregivers exist, but the instruments often focused primarily on a single or few aspects of being a caregiver, e.g. reactions of being a caregiver (e.g. The Caregiver Reaction Assessment [Citation19]), difficulties/burdens of being a caregiver (e.g. Caregivers Assessment of Difficulties Index [Citation20] and Zarit Burden Interview [Citation21]), the treatment of the patient (e.g. FAMCARE [Citation22]), or information needs regarding the patient's treatment or prognosis (e.g. FAMCARE [Citation22] and FIN [Citation23]). No existing questionnaire or combination of existing questionnaires covered the two research questions exhaustively, and we therefore considered is necessary to develop a new questionnaire.

The aim of this paper is to describe the development of a new questionnaire for survey purposes that measures caregiving tasks and consequences, and caregivers’ needs with a main focus on the interaction with the health care professionals.

Needs may be defined in many ways. In this study we chose an empirical approach, framing aspects perceived and described as problematic, difficult, or missing, and sought after into needs.

We defined a caregiver as any person (outside the health care system) involved in the patient's disease course. The involvement did not demand performance of specific tasks. Thus, a caregiver could be a spouse, family member, friend, colleague, etc.

Material and methods

Literature review

To identify themes that could be relevant to cover in the questionnaire, existing literature was searched and reviewed. The search was done in PubMed, using the search words ‘cancer’ and different terms for ‘caregivers’ (e.g. carers, relatives, spouses, next of kin). As the searches resulted in an enormous number of hits, and as reviews turned out to be highly useful for identification of relevant themes, the search was limited to reviews. Based on the abstract, reviews that seemed to be dealing with cancer caregivers’ experienced tasks, consequences, and needs were selected for further review. Through a thorough reading of these, reviews not relevant for the two research questions were eliminated. In the remaining relevant reviews, themes concerning the two research questions were identified.

Focus group interviews

To elaborate and supplement the results of the literature review, i.e. to discover any possible relevant themes concerning Danish caregivers’ situation not described in the international literature, we carried out focus group interviews with Danish cancer patients’ caregivers, cancer patients, clinicians and cancer counselors.

The interviews with patients were carried out to ensure an ‘outside’ view on the caregivers’ situation, and clinicians and counselors were interviewed, as they were assumed to have a vast experience with caregivers and therefore might be able to see some general tendencies. Among the interviewed caregivers were also a separate group of bereaved caregivers. We thus sought to obtain as broad a picture of the caregivers’ experiences and needs as possible.

Recruitment of participants. Cancer patients and their caregivers were recruited from two departments of oncology (including an outpatient clinic), one department of gynecology, and one department of gastrointestinal surgery in three Danish hospitals in the Copenhagen area. Patients and caregivers were either invited by letter, or approached and invited in person. Clinicians were recruited through contact facilitated by the department managements in one department of oncology, one department of gynecology, and one department of palliative medicine, in three hospitals in the Copenhagen area. Cancer counselors were recruited from The Danish Cancer Society's telephone counseling and its cancer counseling center in Copenhagen.

All participants received oral and written information about the study complying with the Helsinki II Declaration.

Interview guide. The interview guide was developed on basis of the two research questions and was similar across the focus groups. The participants were asked about caregivers’ experiences, elements that could influence the experience of being a cancer patient's caregiver, caregivers’ needs and to what extent the needs were met by the health care system, and suggestions for changes in the health care system to improve the conditions of the caregivers. At first, an open interview technique was used, ensuring the possibility of discovering new themes not present in the literature, and later the participants were asked about specific themes found in the literature. The scene was laid to describe both positive and negative experiences.

Analysis of the focus group interviews. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed (by LL) using the method ‘qualitative content analysis’ [Citation24]. This pragmatic method aims at putting together and summing up the essential parts of the data material. The result is a descriptive summary of the informative parts of the material. In the first step of the analysis, the transcripts were read and a general view of the material was formed. Subsequently, texts elucidating being a caregiver were extracted from each interview. Finally, texts concerning similar aspects were grouped, and overall themes were formed.

To ensure consensus and reduce coding bias, the content and analyses of the focus group interviews were discussed with another researcher participating in the focus group interviews (LR).

Themes selection and item drafting

The relevance of themes for this study was determined on basis of the two research questions. The relevant themes from the literature and the focus group interviews were compared for similarities and differences by investigating their contexts, ensuring that all themes were distinct, or otherwise united. By combining the results of the literature review and the focus group interviews, a list of themes to cover in the questionnaire was developed. Themes were included on the list, regardless of whether they were identified in both the literature and the focus group interviews, or in only one of the two. Subsequently, items covering the relevant themes were drafted. Regarding the formulation of the items, we aimed at using a language as close as possible to the language observed in the focus group interviews with patients and caregivers.

Cognitive interviews

The drafted questionnaire was evaluated by cognitive interviews to examine how the respondents comprehended, processed and answered the items [Citation25–27]. This technique can form the basis for modifications, ensuring a reduction of problems regarding comprehension and response [Citation25].

Recruitment of respondents. Respondents were recruited in person at an oncology outpatient clinic in a Copenhagen hospital. The only inclusion criterion was being a cancer patient's caregiver. All respondents received oral and written information about the study complying with the Helsinki II Declaration.

Evaluation technique and analysis. All items in the questionnaire draft were evaluated by cognitive interviews. The evaluation took place in parallel with the development of the questionnaire. Thus, several versions of the questionnaire were evaluated. This approach made it possible to adjust identified problems and evaluate the changes in new versions of the questionnaire as previously demonstrated [Citation27].

We carried out face-to-face interviews, using a ‘verbal probing’ technique [Citation25], and telephone interviews, using the ‘think aloud’ technique [Citation25] supplemented by verbal probing when problems were observed. The interviews were recorded, and notes about observed problems were made by the interviewer (LL) during each interview, and by another researcher (LR) shortly after each interview. The notes were compared and discussed, and revisions in the questionnaire were made when relevant. Each version of the full questionnaire (both original and revised items) was evaluated by new respondents.

Translation of the questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed in Danish. It was subsequently translated into English by two forward translations (resulting in a consensus version) and two back translations as described in the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Group translation procedure [Citation28]. In the Danish version of the questionnaire, we used the broad term ‘paaroerende’ for both patient and caregiver, as it contains all of a person's close social relations (i.e. spouse, family members, friends, possibly also colleagues, etc.). In English, no similar term exists, and when translating the questionnaire into English we chose to ‘split’ the term and use the terms ‘patient’ and ‘caregiver’ to obtain the most equivalent translation.

Results

Literature review

During the literature review, several reviews were assessed. Based on the abstracts, 54 reviews were selected for further review, as they seemed to be dealing with cancer caregiving tasks and consequences, and caregivers’ needs. A thorough reading and evaluation revealed that 14 of the 54 reviews were most relevant [Citation3–14,Citation16,Citation29]. These reviews contained both qualitative and quantitative studies.

Based on the two research questions, relevant themes in the 14 reviews were identified, elucidating tasks, consequences and needs, as presented in (column 2).

Focus group interviews

Participants. We completed eight focus group interviews with a total of 39 persons: three groups with cancer patients’ caregivers, including one group with bereaved caregivers (16 persons in total), two groups with cancer patients (12 persons), two groups with clinicians (physicians, nurses, social workers and psychologists) (seven persons), and one group with cancer counselors (four persons) (see background information in ). The focus group size varied from two to eight participants.

Table I. Background information of the participants in the focus group interviews.

Analysis of the focus group interviews. The focus group interviews had an average duration of 95 minutes (range 58–149 minutes). Six interviews were fully transcribed, and the two remaining interviews were partly transcribed, one because of technical problems during the recording, and one because of irrelevant parts (i.e. not dealing with caregivers).

The themes identified in the focus group interviews and considered relevant for this study are presented in (column 3).

Table II. Themes coved by the new questionnaire. The identified and relevant themes are listed in column 1, and the origin of the themes is listed in column 2 (the literature) and 3 (focus group interviews). Column 4 shows the item numbers in the new questionnaire covering each theme.

The four themes ‘the caregiver focuses on the patient’, ‘contact persons’, ‘conflicts between patients’ and caregivers’ wishes, needs and experiences’ and ‘reactions and needs of children and adolescents as caregivers’ were not considered relevant or feasible for our research questions and were excluded in the further development of the questionnaire.

Drafting of items

By uniting the results of the literature review and the focus group interviews, a complete list of themes to cover in the questionnaire was developed (, column 1).

Between one and seven items were developed for each of the listed themes (, column 4), depending on the number of items necessary to cover the theme sufficiently, all in all constituting the new questionnaire draft.

As our focus was on the caregivers’ experiences and needs during the disease course as a whole (which was explained to the caregivers in the questionnaire introduction), items were not given time frames. The response categories were inspired from the response categories in a large Danish survey, called ‘The Cancer Patient's World’ [Citation18], investigating cancer patients’ needs. A validation of the response categories in that study showed that the response category ‘always’ (representing full satisfaction) was often considered too definitive and therefore rarely used [Citation30]. To soften up this answer category and make it more accessible – yet, without interrupting the difference between the best and second best (‘most of the time’) response category – we changed the response category to ‘always / almost always’. Likewise, the opposite response category ‘never’ was soften up to ‘rarely / never’.

Cognitive interviews

The questionnaire draft was evaluated by cognitive interviews with 24 caregivers. Three interviews were face-to-face, and 21 were by telephone. This process led through eight versions of the full questionnaire, and furthermore, two items in the final version were evaluated in eight additional face-to-face interviews ().

Table III. Characteristics of the 24 respondents in eight cognitive interviewing rounds, evaluating different versions of the new questionnaire.

summarizes the process and results of the cognitive evaluation. The table describes the observed problems, how the problem was attempted to be solved, and with which result. As the table shows, most often the revision of a problematic item led to a full elimination of the problem (15 items: 2, 3, 14–24, 15 and 31). Yet, in some cases the problem persisted after the revision (seven items: 5, 7, 8, 38, 39, 40 and 41), although to a smaller extent. In these cases, the respondents were judged to have general difficulties understanding any questionnaire, were affected by the interview situation, or forgot to read the item or the introduction text properly, and therefore we found no reason for further revision of these items.

Table IV. The process and results of the cognitive evaluation of the questionnaire. The left column describes the observed problem. The right columns show in which version(s) of the questionnaire the problem was present (the fraction shows the number of respondents presenting the problem divided with the number of respondents evaluating the item), and how the problem was attempted solved.

In addition to the changes based on the cognitive evaluation, we made some changes based on increased insight obtained during the work. The changes included splitting items in two, using all verbs in the same tense, underlining words, changing the order of items, changing layout, and making shorter and less complicated items.

Concerning the response categories, these were also evaluated during the cognitive interviews, but no problems regarding the selection or range of response categories or the process of choosing a response category were observed. However, a few minor adjustments were made based on our own insights.

All these changes were evaluated during the subsequent cognitive interviews, ensuring that they did not cause any problems.

We ended the evaluation of the questionnaire at the point, where we observed no more general or obvious problems with the comprehension or the response process. The final version of the questionnaire, called the Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs Questionnaire (CaTCoN) contains 41 newly developed items and is to be found in the online version of the journal, at http//informahealthcare.com/doi/10.3109/0284186X.2012.681697.

Discussion

The CaTCoN was developed on the basis of a literature review and focus group interviews, and during the development it was continuously evaluated by cognitive interviews, thus forming a solid basis for the revisions.

Generally, there was good agreement between the results from the literature review and the focus group interviews. Yet, some tasks, consequences and needs were only identified in the literature. For example, the theme ‘positive psychological and social consequences’ was found in the literature, but was not brought up in any of the focus groups. The reason could be that the attention in the focus groups was primarily on the participants’ negative experiences regarding being a caregiver. But still, the participants were given the opportunity to mention the positive experiences, though not asked directly. In the CaTCoN, we have developed items examining positive consequences. Conversely, some caregiver needs, e.g. needs for specific information, better physical settings for caregivers at the hospitals, and to be able to take ‘time off’ from the role as caregiver that were identified in the focus groups, were not found in the literature review. In this way, the focus group interviews strengthened the development of the CaTCoN by providing new knowledge, ensuring that items were developed to investigate these aspects further.

Some themes identified in the literature or focus group interviews regarding the caregivers’ situation were not considered relevant or feasible for the intended survey, and consequently these were not included on the list of themes, which should be covered by the CaTCoN. Several themes identified in the literature were excluded, e.g. the theme ‘financial support to the patient’, which is rarely relevant when investigating Danish caregivers’ situation, because the Danish welfare system provide financial support to the patient. Four themes from the focus groups were excluded: The theme ‘the caregiver focuses on the patient’ was excluded, because this was considered an ‘inherent condition’ and the tasks, consequences and needs arising from this theme were covered by other themes. The theme ‘contact persons’ (at hospitals) was excluded, because this theme was mainly patient related, and because the most important aspects in the theme were covered sufficiently by the theme ‘information’. The theme ‘conflicts between patients’ and caregivers’ wishes, needs and experiences’ was excluded after realizing that it could be difficult to get honest answers regarding this theme if patients and caregivers were filling in the questionnaires together or could see each others’ responses. If studies were designed in a way that allows private answering of the questionnaire, this would, however, be an important and interesting theme to cover. Finally, the theme ‘reactions and needs of children and adolescents as caregivers’ was excluded due to the fact that questions to children and adolescents should be designed specifically to the age group to be studied.

The CaTCoN is a ‘stand alone’ questionnaire that, once it is ready for use, can be used, analyzed and interpreted independently of other instruments. Yet, as we found that the theme ‘information about treatment’ was covered sufficiently by existing questionnaires, we chose to develop only one item concerning this theme and instead set the scene for using existing questionnaires together with the CaTCoN. That is, should there be a particular interest in gaining knowledge about caregivers’ experiences concerning the patient's treatment and the information about the patient's treatment and prognosis, existing questionnaires focusing on these aspects, e.g. FAMCARE [Citation22] and FIN [Citation23], could supplement the CaTCoN. Likewise, if knowledge about general aspects such as self-rated health is needed, the CaTCoN could be supplemented by existing questionnaires like, e.g.SF-36 [Citation31].

Regarding the cognitive evaluation of the CaTCoN, the original plan was to carry out only face-to-face interviews. In this way, the respondents would be followed visually, enabling observations of long pauses, problems regarding answering the items, etc. However, since many of the respondents lived far away, we decided to carry out telephone interviews with some of the respondents. When using the ‘think aloud’ technique during the telephone interviews we experienced that we were able to obtain the needed information. Therefore, after evaluating version 4 of the questionnaire, we decided to carry out the remaining interviews as telephone interviews.

During the cognitive evaluation, we made two important observations. First, some items were directed mainly at the closest caregivers such as spouses/partners. Respondents who were parents or adult children of the cancer patients and therefore did not see the patient on daily basis or were not deeply involved in the patient's disease indicated that some items were not relevant in their situation. This indicated that it was relevant to include the ‘don't know / not relevant’ response category. Second, some patients followed the caregivers who were filling in the questionnaire very closely and gave comments along the way during the cognitive interviews. In this way, the respondent could be influenced by others’ opinions, and this may have consequences for the results obtained by a questionnaire like ours. This also confirmed that it would have been inappropriate to include items concerning the theme ‘conflicts between patients’ and caregivers’ wishes, needs and experiences’ in the questionnaire.

In the first rounds of cognitive interviewing, the CaTCoN was evaluated by relatively few respondents, as we captured obvious and fundamental problems that we wanted to eliminate right away. The decreasing number of problems observed during the evaluation rounds shows that we were able to discover and eliminate weaknesses. A similar pattern was seen in a previous study [Citation27], thus illustrating the usefulness of cognitive interviewing in improving questionnaires. It is our conclusion that cognitive evaluation during the development of a questionnaire is highly effective.

Limitations

The relatively small number of participants in the focus groups could be considered a weakness in our study, but we felt that the field was well covered, as the results from the different focus groups were quite similar, and generally close to the results of the literature review.

The CaTCoN aims to measure the extent of cancer caregivers’ help and support to the patient, caregiving consequences, and the caregivers’ needs, mainly concerning the interaction with the health care professionals. Other important aspects of being a caregiver, e.g. conflicts between patients and caregivers, are not measured by the CaTCoN.

The CaTCoN items have varied response categories, which could have an impact on the scoring and interpretation of data. Yet, the impact is attempted minimized by ensuring that all items contain four ordinal response categories and a ‘don't know / not relevant’ category, making the structure of the response categories similar across items.

So far, only the preliminary work to develop the CaTCoN has been carried out, and the psychometric properties of the instrument need to be evaluated before the CaTCoN is ready for general use. If the CaTCoN should be used in other countries, the questionnaire's validity should be tested.

Conclusion

A new questionnaire (the Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs Questionnaire (CaTCoN)) was developed aiming to measure the extent of cancer caregiving tasks and consequences, and the caregivers’ needs, mainly concerning information from and communication and contact with the health care professionals. To the best of our knowledge, no other questionnaire with this delineation exists. During the development, the questionnaire was evaluated by cognitive interviews to reduce problems regarding comprehension and response. At this point, only the initial developmental work has been carried out. Psychometric analysis reviewing item content, determining validity and reliability and whether any items form common scales for the purposes of scoring and interpretation need to be carried out before the CaTCoN is ready for use.

www.informahealthcare.com/mmy/doi/10.3109/0284186X.2012.681697

Download PDF (137.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The research was supported by grants from the Danish Cancer Society (Grant OKV 08007). The sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. No conflict of interest exists for any of the authors.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Hagedoorn M, Buunk BP, Kuijer RG, Wobbes T, Sanderman R. Couples dealing with cancer: Role and gender differences regarding psychological distress and quality of life. Psychooncology 2000;9:232–42.

- Blanchard CG, Albrecht TL, Ruckdeschel JC. The crisis of cancer: Psychological impact on family caregivers. Oncology (Williston Park) 1997;11:189–94.

- Le T, Leis A, Pahwa P, Wright K, Ali K, Reeder B. Quality-of-life issues in patients with ovarian cancer and their caregivers: A review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2003;58:749–58.

- Haley WE. Family caregivers of elderly patients with cancer: Understanding and minimizing the burden of care. J Support Oncol 2003;1:25–9.

- Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:213–31.

- Resendes LA, McCorkle R. Spousal responses to prostate cancer: An integrative review. Cancer Invest 2006;24:192–8.

- Kotkamp-Mothes N, Slawinsky D, Hindermann S, Strauss B. Coping and psychological well being in families of elderly cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2005;55:213–29.

- Laizner AM, Yost LM, Barg FK, McCorkle R. Needs of family caregivers of persons with cancer: A review. Semin Oncol Nurs 1993;9:114–20.

- Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors: Across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer 2008;112:2556–68.

- Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, Triemstra M, Spruijt RJ, van den Bos GA. Cancer and caregiving: The impact on the caregiver’s health. Psychooncology 1998;7:3–13.

- Glajchen M. The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. J Support Oncol 2004;2:145–55.

- Pitceathly C, Maguire P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives: A review. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:1517–24.

- Given B, Sherwood PR. Family care for the older person with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 2006;22:43–50.

- Honea NJ, Brintnall R, Given B, Sherwood P, Colao DB, Somers SC, . Putting evidence into practice: Nursing assessment and interventions to reduce family caregiver strain and burden. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2008;12:507–16.

- Ko CM, Malcarne VL, Varni JW, Roesch SC, Banthia R, Greenbergs HL, . Problem-solving and distress in prostate cancer patients and their spousal caregivers. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:367–74.

- Hudson PL, Aranda S, Kristjanson LJ. Meeting the supportive needs of family caregivers in palliative care: Challenges for health professionals. J Palliat Med 2004;7:19–25.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc.; 1984.

- Grønvold M, Pedersen C, Jensen CR, Faber MT, Johnsen AT. Kræftpatientens verden – en undersøgelse af hvad danske kræftpatienter har brug for. København: Kræftens Bekæmpelse; 2006.

- Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health 1992;15:271–83.

- Nolan M, Grant G. Regular respite: An evaluation of a hospital rota bed scheme for elderly people. London: Age Concern Institute of Gerontology; 1992.

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980;20:649–55.

- Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: Measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med 1993;36:693–701.

- Kristjanson LJ, Atwood J, Degner LF. Validity and reliability of the family inventory of needs (FIN): Measuring the care needs of families of advanced cancer patients. J Nurs Meas 1995;3:109–26.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40.

- Willis G. Cognitive interviewing. A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005.

- Tourangeau R. Cognitive sciences and survey methods. In: Jabine T, Straf M, Tanur J, Tourangeau R, editors. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology: Building a bridge between disciplines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1984. p. 73–100.

- Watt T, Rasmussen AK, Groenvold M, Bjorner JB, Watt SH, Bonnema SJ, . Improving a newly developed patient-reported outcome for thyroid patients, using cognitive interviewing. Qual Life Res 2008;17:1009–17.

- Cull A, Sprangers M, Bjordal K, Aaronson N, West K, Bottomley A. EORTC quality of life group translation procedure. 2nd ed. 2002. Available from: http://groups.eortc.be/qol/downloads/200202translation_manual.pdf

- Docherty A, Owens A, Asadi-Lari M, Petchey R, Williams J, Carter YH. Knowledge and information needs of informal caregivers in palliative care: A qualitative systematic review. Palliat Med 2008;22:153–71.

- Ross L, Lundstrøm LH, Petersen MA, Johnsen AT, Watt T, Groenvold M. Using method triangulation to validate a new instrument (CPWQ-com) assessing cancer patients’ satisfaction with communication. Cancer Epidemiol 2012;36:29–35.

- Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey. Manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993.