Abstract

Purpose. To investigate long-term development of sickness absence and disability pension among colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors compared to matched cancer-free controls, and to assess to what degree socio-demographic and disease characteristics influence these outcomes. Patients and methods. In a register-based cohort study with data from the Cancer Registry of Norway and longitudinal data from other national registries, 740 patients with CRC diagnosed 1992–1996 at the age 45–54 years were observed up to 14 years post-diagnosis. Also 740 matched controls were observed over the same time period. Results. During the first year after diagnosis, 85% of the CRC survivors were on sick-leave at some point, compared to 19% of the controls. Among survivors with localized cancer, 21% were on sick-leave 12 months after diagnosis, versus 33% with regional, and 52% with distant cancer. Survivors with rectum cancer were more likely than colon cancer survivors to be on sick-leave the first year after diagnosis (OR 2.53, 95% CI 1.61–3.98). CRC survivors were at higher risk for disability pension (DP) than controls, depending on extent of disease. Hazard ratios for DP were 1.67 (95% CI 1.13–2.46) for survivors with localized cancer, 3.12 (95% CI 2.06–4.72) for regional, and 10.13 (95% CI 4.17–24.62) for distant cancer, respectively. In survivors, distant cancer, low level of education, not having children < 18 years in the household, pre-diagnostic sick-leave and not being employed at diagnosis were associated with increased likelihood for DP. Conclusion. A considerable proportion of CRC survivors, for years after diagnosis, will experience reduced work ability compared to controls. Rehabilitation and workplace adjustment to reduce sickness absence and improve work ability should be a long-term concern.

With improvements in survival rates and awareness of long-term and late effects after cancer, work- related issues have become increasingly relevant for cancer survivors [Citation1]. Despite a growing literature on work and cancer survivorship, few longitudinal studies have investigated this topic in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC), which is the third most prevalent cancer worldwide [Citation2] and the second most prevalent cancer in Europe [Citation3]. At the time of diagnosis more than 30% of the patients are below 65 years and thus within working age [Citation4]. Since participation in work life is important for identity, self esteem, social inclusion and economic status [Citation5], not resuming work may have considerable consequences for CRC survivors and their families, and also lead to costs for workplaces and society.

Most CRC survivors who are working prior to diagnosis will return to work [Citation6–8]. However, those who receive adjuvant treatment may be less likely to return to work up to 12 months post-diagnosis or return to work later than those who only have surgery [Citation7–10]. Also, return to work may be less likely and permanent retirement more likely after a period of sickness absence in survivors with advanced extent of CRC at diagnosis compared to survivors diagnosed with CRC in early stage [Citation11].

Previous Nordic studies have shown reduced employment rates [Citation12,Citation13] and increased risk for early retirement [Citation14,Citation15] among CRC survivors compared to cancer-free individuals in the general population. This may be due to long-term physical and psychological health problems such as bowel dysfunction, urinary incontinence, fatigue, pain, depression, anxiety and sleep difficulty [Citation16–18] that may reduce work ability. Such reduction may lead to extended or repeated periods of sickness absence and increased risk for disability pension. Some studies have also suggested an impact from job type and education on work after CRC [Citation10–12], though these results are disputed [Citation7,Citation8].

The aim of this study is to investigate long-term development of sickness absence and disability pension (DP) among CRC survivors compared to matched cancer-free controls, and to assess whether socio-demographic and disease characteristics influence these outcomes.

Patients and methods

Data sources and patient sampling

This cohort study was based on data from several Norwegian population-based registries: The Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN), the Event data base (FD-Trygd) of Statistics Norway (SSB) established in 1992, The Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration (NAV), The Norwegian Population Registry and The National Cause of Death Register. The unique personal identity number of all Norwegian citizens enabled linkage of data from these registries.

CRN identified and provided diagnostic data on 972 individuals who were diagnosed with CRC as first lifetime malignancy between 1992 and 1996 at the age 45–54 years. Data included extent of cancer (local, regional, distant or unknown) at time of diagnosis and cancer site (colon or rectum). The CRN contains close to complete national data on date of diagnosis and type of cancer [Citation19]. Information on primary treatment and relapse has not been systematically reported to the CRN, and such incomplete data were considered unsuitable for this study.

SSB randomly drew one control pair-wise matched on sex, age, level of education and municipality for each CRC survivors from The Population Registry, and the controls did not have a record in CRN. Longitudinal data on demography, employment, annual income, sickness benefits and disability pension were delivered from FD-Trygd for all patients and controls. The FD-Trygd data base is appropriate for studies concerning social insurance and social policy and contains events and longitudinal data collected from several administrative and statistical registries for the entire Norwegian population. Social security is granted by the National Insurance Scheme administered by The National Work and Welfare Administration (NAV). NAV data are primarily transferred to SSB and available for research through FD-Trygd. The medical diagnoses, on which the granting of sickness benefits and DP are based, were delivered to this study after approval by NAV. Data on date and cause of death were delivered by the appropriate national register.

The study sample consisted of 740 pairs, after 232 pairs had been excluded due to pre-diagnostic DP in either the patient (n = 100), the control (n = 113) or both (n = 16) or to pre-diagnostic death of the controls (n = 3). Patients and controls were followed from January 1, 1992 until they died, were censored due to retirement (age of retirement has been 67 years during the whole study period) or ended observation on December 31, 2005. Within each pair, baseline for the control was the date of diagnosis for the patient. Hence, the maximum observation time varied between nine and 14 years from diagnosis.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Norwegian Committee of the Southern Health Region for Ethics in Health Research and by the Data Inspectorate of Norway. Based on de-identified data from national registries, no written informed consent was required.

Standards of treatment

Surgical resection has been the main treatment for stage I-III colon cancer during the study period. In 1993 the use of Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) [Citation20] were implemented nationally for rectal cancer, and was performed on 78% of the patients in 1994, increasing to 92% in 1997 [Citation21]. No national guidelines on adjuvant treatment had been implemented when our sample had their primary treatment.

Sick-leave and sickness benefits

Working individuals are entitled to sickness benefits from NAV. If working disability is documented by a doctor’s certificate, sickness benefits are paid for up to 52 weeks and commonly as 100% of previous employment income. Thereafter, 26 weeks of work are required to qualify for new sickness benefits. After 52 weeks individuals unable to return to work are transferred to rehabilitation or DP schemes. The first 16 days of a sick-leave period in Norway are paid by the employer.

Sick-leave proportions each month comprised individuals who received sickness benefits from NAV for at least one day during that month. The measurement started at 12 months pre-diagnosis and only concerned individuals employed at time of diagnosis. Individuals were right censored at time of DP or death.

Length of sickness absence per year [Citation22] was calculated as the number of days on sick-leave during each year of investigation among sick-listed individuals. Sick-leave was graded between 20% and 100%, and degrees < 100% were converted into whole days.

Sick-leave in the year prior to diagnosis was separated into three categories: no sick-leave, short-term (1–55 days) and long-term sick-leave (≥ 56 days). Long-term sick-leave is considered to start after eight weeks, due to the extended sickness absence certificate which the responsible doctor must submit at that time.

DP

Norwegian citizens of working age are entitled to DP if their work ability is permanently impaired by at least 50% for reasons of disease or injury after appropriate rehabilitation has been performed. DP is graded between 50% and 100%, and we defined individuals on DP from the date they were granted such benefit.

Socio-demographic variables

Level of basic education was dichotomized as high (> 12 years) or low (≤ 12 years). Children aged < 18 years in the household at diagnosis were present or absent. Age at diagnosis was separated into < 50 and ≥ 50 years. Marital status at time of inclusion was either married or unmarried. Residence area was either urban or rural.

Statistics

Socio-demographic differences between patients and controls and between sexes were assessed by χ2-test. Missing values were handled as described previously [Citation23].

For the analysis of sick-leave proportions we preferred monthly aggregates defined as dichotomous variables, where individuals with at least one sick-leave day during the specific month were assigned value 1, while those without any sick-leave days got 0. Logistic regression for repeated measurements (SAS GLIMMIX procedure) with time as (non-linear if relevant) predictor and random effects for intercepts was then applied for the analysis of sick-leave pattern. Odds ratios (OR) adjusted for pre-diagnostic sick-leave, level of education and children < 18 years in the household, i.e. data not utilized in the matching procedure, were estimated within each extent of the disease for the first five years post-diagnosis with controls as reference group. Also, sick-leave proportions for survivors with colon cancer were compared to those of rectum cancer survivors. The Mann-Whitney test was used to examine differences in annual length of sickness-absence between patients and controls by extent of disease.

Cumulative probability estimates for DP during follow-up were depicted as Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and the log-rank test was used to assess differences in the DP distributions. Proportional hazards assumptions were checked by visual inspection of log minus log plots. HR for DP for patients compared to controls adjusted for pre-diagnostic sick-leave, level of education, employment at diagnosis and children < 18 years in the household was estimated using the Cox proportional hazard model. HR for patients by extent of disease was adjusted for available demographic and clinical data.

The analyses were performed in PASW for Windows 18 and SAS version 9.3. Tests applied were two-sided, and the level of significance was set at 5%.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Patients and controls did not differ on socio- demographic characteristics. No significant differences were observed in extent of disease at diagnosis between male and female survivors (). Mean age at diagnosis for both men and women was 51 years. Significantly larger proportions of men than women were employed, had high education and high income. More men than women had children < 18 years in the household. Mean observation time in survivors was 10.3 years for localized, 7.8 years for regional and 2.0 years for distant CRC s and 11.6 years for controls.

Table I. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer and their matched controls at time of diagnosis.

Sick-leave

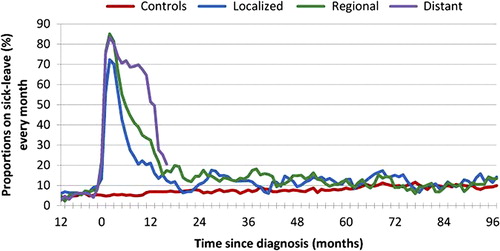

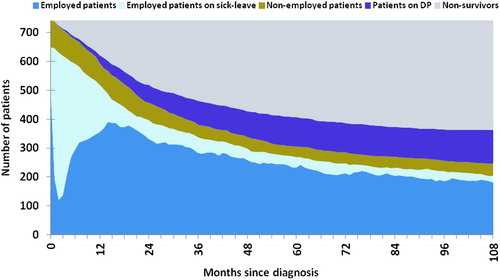

Among the 648 survivors employed at time of diagnosis, 85% were on sick-leave at some point during the first year after diagnosis, compared to 19% among 626 employed controls. Sick-leave proportions peaked during the first months after diagnosis and then declined over time (). Among survivors with localized cancer, 21% were sick-listed 12 months after diagnosis, versus 33% with regional, and 52% with distant cancer. Proportions of sick-listed controls were below 7% throughout the first post- diagnostic year. Survivors were significantly more likely than controls to be on sick-leave during the first two years, and survivors with localized cancer also during the third year (). No differences in sick-leave rates between patients and controls were observed later during follow-up. The numbers of survivors under risk for sick-leave decreased substantially over time as survivors were censored due to DP or death (). Two years after diagnosis, only 19% of survivors with distant CRC were alive and did not receive DP.

Figure 1. Sick-leave proportions during loliow-up among individuals employed at diagnosis. Individuals were censored at time of DP or death.

Table II. Adjusted odds ratio for sick-leave in CRC by extent of disease compared to controls (reference group).

Table III. Median length (days) of sickness absence per year in sick-listed patients by extent of disease and controls with p-values (controls as reference).

Compared to survivors with localized cancer (reference group), adjusted ORs for sick-leave the first and second year were 3.78 (95% CI 2.05–6.94) and 2.17 (95% CI 1.19–3.93), for regional cancer and 2.31 (95% CI 1.05–5.10) and 2.32 (0.85–6.34) for distant cancer, respectively. Thereafter, sick-leave rates were not significantly different from that of local cancer.

Survivors with rectum cancer were more likely than colon cancer survivors to be on sick-leave, but only the first year after diagnosis (adjusted OR 2.53, 95% CI 1.61–3.98). In survivors, the only socio-demographic characteristics associated with sick-leave probability besides diagnosis was pre- diagnostic sick-leave (data not shown).

shows that compared to sick-listed controls length of sickness absence per year was significantly extended at one and three year(s) after diagnosis in sick-listed survivors with localized and regional cancer, and also at five years in survivors with localized cancer.

DP

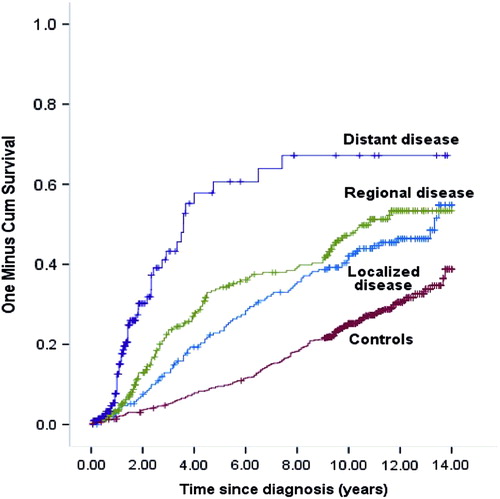

Probability estimates for having DP during follow-up are depicted in . According to the extent of CRC, the DP distributions were significantly different from that of controls, but not significantly different between patients with localized and regional cancer. Compared to controls, the adjusted HR for DP was 1.67 (95% CI 1.13–2.46) for patients with localized cancer, 3.12 (95% CI 2.06–4.72) for regional, and 10.13 (95% CI 4.17–24.62) for distant cancer. Among patients who were alive at the end of the follow-up period, adjusted HR for DP was 1.53 (95% CI 1.1–2.2) compared to controls.

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence. Probability for disability pension during follow-up. Kaplan-Meier plot (1-survival).

At the end of the observation period, 36% of the patients and 29% of the controls had become DP recipients. Median time from diagnosis to DP was 3.1 years for patients and 6.9 years for controls. Among the 52% of patients who died during follow-up, 34% had obtained DP.

Distant cancer, low level of education, unemployment at diagnosis, sick-leave in the year prior to diagnosis, and not having children < 18 years at home were all covariates significantly associated with increased hazard for DP among patients in a stratified multivariate Cox regression analysis (). Regional cancer, cancer site, residence area, marital status, gender and age were non-significant covariates. The distribution of employment, sick-leave, unemployment, DP and survival for the cohort of survivors during nine years of observation is presented in .

Figure 3. Work life participation after colorectal cancer. Distribution of employment, sick-leave, unemployment, disability pension and survival during follow-up.

Table IV. Multivariate HRs and 95% confidence interval for receiving disability pension for CRC survivors by extent of disease.

Discussion

The first year after diagnosis 85% of the survivors employed at diagnosis had been on sick-leave at some time point. At three months 78% were sick-listed, decreasing to 50% at six months and 32% at one year. Also later in the observation period, sick-leave rates and length of absence were significantly increased for survivors compared to controls, depending on the extent of disease. ORs for sick-leave the second year ranged from OR 2.3 for localized cancer, to OR 5.0 and OR 5.7 for regional and distant cancer, respectively.

Furthermore, survivors were more likely than controls to receive DP, even those who survived throughout the extensive observation period. While survivors with rectum cancer were more likely to be on sick-leave the first year than colon survivors, no significant association with DP was observed for cancer site.

Our sick-leave patterns during the first post- diagnostic year are similar to those of CRC patients in a Swedish study [Citation6], probably explained by the resemblance of the social security systems in the two countries. Our 50% on sick-leave at six months post-diagnosis was somewhat lower than the 61% not working as reported in a British study [Citation9]. Sick-leave of 32% at one year post-diagnosis was close to the 35% not working among Australian CRC patients [Citation7] and the 38% among Danish CRC survivors [Citation11]. Sanchez et al. reported delayed return to work beyond two months post-diagnosis for one third of American CRC survivors [Citation8].

The observed peak in sick-leave rates the first months after diagnosis suggests that primary treatment have a negative impact on short-term work ability in most CRC survivors. Thus, the very high OR value observed the first year after diagnosis can be explained by the fact that nearly all CRC patients are on sick-leave at some point that year.

Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy may furthermore prolong the duration of post-treatments. Sanchez et al. have demonstrated that delayed return to work beyond two months in CRC patients was related to chemotherapy [Citation8]. Chemotherapy or a combination of treatments were associated with poorer self-assessed work ability during six months follow-up and with a greater likelihood of not working after six months among CRC patients in the study by Baines et al. [Citation9]. Gordon et al. demonstrated that radiation therapy among men and chemotherapy among women were associated with not working one year post-diagnosis [Citation7].

Chemotherapy for colon cancer stage III patients < 75 years was introduced nationwide in Norway in 1997 [Citation24], thus survivors in our study were included and had their primary treatment before national guidelines on adjuvant treatment were implemented. However, a multi-center phase III study on adjuvant chemotherapy in patients < 75 years with colon and rectum cancer stage II and III was conducted between 1993 and 1996 [Citation24]. Patients were randomized to surgery alone (n = 211) or to adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 214). This implies that an unknown number of our CRC sample received chemotherapy.

The lack of treatment data is a major weakness of our study which also precluded investigation of possible mechanisms behind longer sickness absence in rectum versus colon cancer survivors observed in the first year after diagnosis. Still, differences in adjuvant treatment strategies between colon and rectum cancer survivors are not evident as both groups were included in the previously described study [Citation25] and the use of radiotherapy in rectum cancer was very low in the mid-1990s [Citation21,Citation26]. In a Norwegian national cohort of rectal cancer patients, the rate of anastomotic leakage following Total Mesorectal Excision was 12% between 1993 and 1999 [Citation27]. Such a serious complication may have negative impact on work ability in rectum cancer survivors. Also, more incontinence for gas and solid stools in patients with a low versus higher anastomosis after anterior resection of rectal cancer has been suggested [Citation28]. Differences in symptoms after surgery should therefore be considered relevant for the observed differences in sick-leave probability.

The quality of life in rectal cancer patients with or without permanent colostomy has been compared in a Cochrane review based on 35 studies and more than 5000 participants, but no firm conclusions could be drawn [Citation29]. Nor was having a stoma found to be related to less or later resumption of labor in rectal cancer survivors [Citation10].

In the present study, survivors with distant CRC had short life expectancy, and they experienced increased probability for sick-leave and DP compared to those with localized CRC. This observed difference in work ability by extent of disease may be due to health differences associated with cancer. In a Dutch study, CRC survivors with stage IV at diagnosis almost six times more frequently reported poor perceived health and were four times more likely to report functional disability than stage I survivors [Citation30]. Furthermore, given the short remaining life span for most survivors with distant CRC, their priorities may change, and the role of work may become less important. Though, also survivors with better prognosis may reconsider work importance after a cancer diagnosis.

In contrast to a recent French study demonstrating that in a mixed group of cancer survivors married women returned to work more slowly than married men [Citation31], we observed no significant differences in sick-leave probability or length of sickness absence between male and female CRC survivors, nor were significant sex-differences in DP probability observed. Pre-diagnostic sick-leave, not being employed at diagnosis and low level of education were significantly associated with increased probability for DP. These factors may reflect lower work ability and/or flexibility even prior to the CRC diagnosis implying fewer opportunities for work place adjustments and changes after treatment.

Sick-leave rates and return to work rates are not directly comparable outcome measures. Sick-leave is a complex outcome, open to multiple transitions between sick-leave and work and to varying combination of partial sick-leave and part-time work [Citation32]. Our interest was to investigate the use of sickness benefits following the diagnosis of CRC as an expression for work ability, and therefore we did not separate between full and partial sick-leave. Hence, return to work estimates cannot be presented; as such return may occur partially in the transition process between full sickness absence and full work resumption. About 15% of the survivors employed at diagnosis did not receive sickness benefits during the year after diagnosis. Since the first 16 days of a sick-leave period in Norway are paid by the employer, survivors who return to work within this period are not recorded with sickness absence by NAV. Thus, more CRC survivors than we observed may have been on short-term sick-leave.

The steep decline in the sick-leave curves around 12 months after diagnosis, especially for regional and distant cancer survivors, may be due to loss of the right to further sickness benefits, and subsequent transition to rehabilitation allowances, alternatively to improved work ability. However, a limitation of our study is the lack of data regarding rehabilitation allowances. The association between sickness benefits and DP were not investigated due to a strong correlation between these variables and extent of disease. Further, by right censoring the data due to DP or death throughout the observation period, we may assume that the survivors remaining in the analyses have better health and work ability than those who are censored, gradually leading to lower sick-leave rates.

Our findings concerning DP are supported by previous register-based Nordic studies which have demonstrated significantly increased risk of retirement in CRC survivors. Compared to cancer-free controls, the risk for taking early retirement was increased by 74% in male and 80% in female CRC survivors working at the time of diagnosis in a Danish cohort study [Citation15], whereas the risk of retirement were 17% higher in working-age survivors after a history of CRC than controls in a cross-sectional study from Finland [Citation14]. Different study designs may have contributed to the differences in risk estimates.

Whether CRC patients continue to work, are sick-listed or on DP may be influenced by other factors than health status. Coverage and compensation from private or national insurance schemes, unemployment rates, and labor law and regulations are some structural components that may affect work status in CRC patients differently between countries. Our findings have to be understood in the context of the Norwegian social security system with full income compensation for sickness absence up to a year and a strong legal protection against dismissal of sick-listed employees.

Some methodological aspects must be considered in the interpretation of our findings. They reflect patterns of sickness absence and DP for all CRC patients in Norway compared to controls with an extensive observation time. Almost half of the patients died within five years after diagnosis, and about 75% of patient with distant cancer died within two years. The decreasing number of patients eligible for sickness benefits due to DP or death may have lead to less precise sick-leave estimates, especially for survivors with poor prognosis in the first years of follow-up and for all survivors later in the observation period.

Changes in treatment guidelines in accordance with the constantly improving cancer treatment may have reduced the external validity of our study. This is a general problem of longitudinal cohort studies of cancer survivors since current cancer patients are treated according to more recent guidelines. Improved survival rates may for instance lead to decreased numbers of survivors who experience poor health near end-of-life and subsequent reductions in sick-leave and DP after CRC. Possible differences in short- and long-term work ability between survivors by extent of disease associated with neo-adjuvant/adjuvant treatment cannot be disregarded. Nevertheless, we expect our findings to be relevant also for CRC survivors in more recent cohorts as a CRC diagnosis for many individuals still implies demanding and sometimes prolonged treatment, recurrence from CRC still occurs and some survivors have their life expectancy shortened due to CRC.

Conclusion

In this register-based cohort study CRC survivors received sick-leave benefits and DP more often than cancer-free controls, suggesting that CRC is associated with reduced work ability on both a temporary and permanent basis. Rehabilitation and workplace adjustment to reduce sickness absence and improve work ability should be a long-term concern in CRC survivors.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Feuerstein M. Work and cancer survivors. In: Feuerstein M, editor. New York: Springer; 2009.

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893–917.

- Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1374–403.

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr [cited 2 May 2013].

- Peteet JR. Cancer and the meaning of work. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000;22:200–5.

- Sjovall K, Attner B, Englund M, Lithman T, Noreen D, Gunnars B, et al. Sickness absence among cancer patients in the pre-diagnostic and the post-diagnostic phases of five common forms of cancer. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:741–7.

- Gordon L, Lynch BM, Newman B. Transitions in work participation after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32:569–74.

- Sanchez KM, Richardson JL, Mason HR. The return to work experiences of colorectal cancer survivors. AAOHN J 2004; 52:500–10.

- Bains M, Munir F, Yarker J, Bowley D, Thomas A, Armitage N, et al. The impact of colorectal cancer and self-efficacy beliefs on work ability and employment status: A longitudinal study. Eur J Cancer Care 2012;21:634–41.

- van den Brink M, van den Hout WB, Kievit J, Marijnen CA, Putter H, van de Velde CJ, et al. The impact of diagnosis and treatment of rectal cancer on paid and unpaid labor. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1875–82.

- Carlsen K, Harling H, Pedersen J, Christensen KB, Osler M. The transition between work, sickness absence and pension in a cohort of Danish colorectal cancer survivors. Br Med J Open 2013;3.

- Taskila-Brandt T, Martikainen R, Virtanen SV, Pukkala E, Hietanen P, Lindbohm ML. The impact of education and occupation on the employment status of cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2488–93.

- Syse A, Tretli S, Kravdal O. Cancer’s impact on employment and earnings – a population-based study from Norway. J Cancer Surviv 2008;2:149–58.

- Taskila-Abrandt T, Pukkala E, Martikainen R, Karjalainen A, Hietanen P. Employment status of Finnish cancer patients in1997. Psychooncology2005;14:221–6.

- Carlsen K, Dalton SO, Frederiksen K, Diderichsen F, Johansen C. Cancer and the risk for taking early retirement pension: A Danish cohort study. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:117–25.

- Denlinger CS, Barsevick AM. The challenges of colorectal cancer survivorship. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2009;7:883–93.

- Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Quality of life among long-term (>/ = 5 years) colorectal cancer survivors – systematic review. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2879–88.

- Jansen L, Herrmann A, Stegmaier C, Singer S, Brenner H, Arndt V. Health-related quality of life during the 10 years after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: A population-based study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3263–9.

- Larsen IK, Smastuen M, Johannesen TB, Langmark F, Parkin DM, Bray F, et al. Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: An overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1218–31.

- Heald RJ. The ‘Holy Plane’ of rectal surgery. J R Soc Med 1988;81:503–8.

- Wibe A, Moller B, Norstein J, Carlsen E, Wiig JN, Heald RJ, et al. A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer – implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:857–66.

- Hensing G, Alexanderson K, Allebeck P, Bjurulf P. How to measure sickness absence? Literature review and suggestion of five basic measures. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:133–44.

- Hauglann B, Benth JS, Fossa SD, Dahl AA. A cohort study of permanently reduced work ability in breast cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6:345–56.

- Tveit KM.[Adjuvant treatment in operable colonic and rectal cancer. A new possibility]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1997;117:2991–2.

- Dahl O, Fluge O, Carlsen E, Wiig JN, Myrvold HE, Vonen B, et al. Final results of a randomised phase III study on adjuvant chemotherapy with 5 FU and levamisol in colon and rectum cancer stage II and III by the Norwegian Gastrointestinal Cancer Group. Acta Oncol 2009;48:368–76.

- Hansen MH, Kjaeve J, Revhaug A, Eriksen MT, Wibe A, Vonen B. Impact of radiotherapy on local recurrence of rectal cancer in Norway. Br J Surg 2007;94:113–8.

- Eriksen MT, Wibe A, Norstein J, Haffner J, Wiig JN. Anastomotic leakage following routine mesorectal excision for rectal cancer in a national cohort of patients. Colorectal Dis 2005;7:51–7.

- Guren MG, Eriksen MT, Wiig JN, Carlsen E, Nesbakken A, Sigurdsson HK, et al. Quality of life and functional outcome following anterior or abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005;31:735–42.

- Pachler J, Wille-Jorgensen P. Quality of life after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD004323.

- Soerjomataram I, Thong MS, Ezzati M, Lamont EB, Nusselder WJ, van de Poll-Franse LV. Most colorectal cancer survivors live a large proportion of their remaining life in good health. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23:1421–8.

- Marino P, Teyssier LS, Malavolti L, Le Corroller-Soriano AG. Sex differences in the return-to-work process of cancer survivors 2 years after diagnosis: Results from a large French population-based sample. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1277–84.

- Oyeflaten I, Lie SA, Ihlebaek CM, Eriksen HR. Multiple transitions in sick leave, disability benefits, and return to work. – A 4-year follow-up of patients participating in a work-related rehabilitation program. BMC Public Health 2012;12:748.