To the Editor,

Metastatic osteosarcoma is a disease with poor prognosis and dismal outcome [Citation1–3].

Ifosfamide in regular or high dose (14 g/m2) has shown activity in about one third of the cases but renal failure is a limiting complication [Citation4,Citation5]. Gemcitabine/docetaxel has an expected response rate of about 13% and the median overall survival (OS) is nine months [Citation6].

The tyrosin kinase inhibitor sorafenib was recently tested in a phase II study of 35 patients. The progression-free survival (PFS) at four months was 46%, median PFS and OS were four and seven months, respectively. The clinical benefit (partial remission and stable disease) rate was 48% with some responses lasting for more than six months [Citation7].

In vitro studies showed that osteosarcoma cells expressed vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors that are implicated in tumor progression and correlated with worse event-free and OS [Citation8]. It is suggested that inhibitors of these tyrosin kinases can lead to clinical responses. Indeed, daily oral administration of pazopanib, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with activity against VEGF 1, 2, 3, and PDGF [Citation9], given to C3H mice bearing LM8 osteosarcoma xenografts reduced the rate and size of pulmonary metastasis [Citation10].

Moreover, pazopanib has proved effective in patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcoma who failed prior therapy, increasing PFS from 1.6 (placebo arm) to 4.6 months [Citation11].

The Danish Medical Council has established a second opinion committee that could be contacted by doctors on behalf of their patients in order to use off label drugs on experimental basis, outside of clinical trials (Danish Medical Council website information: https://sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/da/sundhed/behandling-og-rettigheder/eksperimentel-behandling).

Based on these considerations, we have tested standard pazopanib dose of 800 mg daily in three consecutive patients with metastatic osteosarcoma who failed standard chemotherapy. The detailed clinical course of these three patients is described below.

Description of cases

Case 1

A 23-year-old male who was diagnosed in 1995 (when he was 10 years old) with osteosarcoma in the left humerus and bilateral multiple lung metastasis. He was treated with chemotherapy and was operated for both primary tumor and lung metastasis. A new metastatectomy was performed in 1999 for solitary lung metastasis.

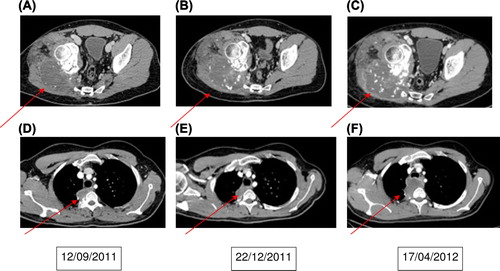

In May 2008 he presented with a biopsy-verified recurrence in the lung (tumor 8 × 8× 6 cm) and a new lesion in the right iliac bone. He obtained complete remission after 10 cycles of ifosfamide/etoposide/MTX as well as operative removal of the tumors in the lung and iliac bone. Six months later, CT scan revealed local recurrence and multiple bilateral lung metastasis. Following progression under standard salvage chemotherapy the patient then started oral pazobanib 800 mg daily in October 2011 (). His first control scan showed stable disease with necrosis of mediastinal metastasis () as well as necrosis and calcification (as a sign of response) in the right gluteal region metastasis (). The second control scan in April 2012 (6 months after treatment start) showed progressive disease () and the treatment was terminated.

Case 2

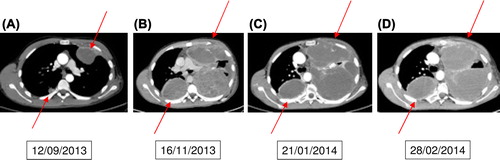

A 21-year-old male was diagnosed in December 2010 with an osteoblastic osteosarcoma in the left proximal humerus and suspicion of bilateral lung metastases. Treatment was initiated according to the EURASMOS-1 study. Repeated CT scans showed remission of the suspected lung metastases and the patient was randomized to receive consolidation treatment with interferon. In February 2012 a CT scan revealed multiple bilateral lung metastasis and a local recurrence in the shoulder region. Due to progression under standard chemotherapy, pazopanib (800 mg daily) was started in July 2013. Radiological evaluation after two months of therapy demonstrated progressive disease () and the treatment was stopped pending inclusion of the patient into a phase I trial. Following the cessation of pazopanib the patient showed clinical signs of rapid progression () and a declining performance status (WHO/ECOG score 3) making him ineligible for any possible clinical trial. Pazopanib was restarted in November 2013 when the patient was bed ridden and with intractable pains. While on pazopanib, he was discharged from the Oncology Department to a hospice. Shortly after discharge, there was a clear and marked improvement of general condition and the patient's use of morphica was reduced. In January 2014 he was discharged from the hospital to his own home and he came walking to his next control in the Oncology Department where CT scanning showed stable disease, though the tumors became more cystic (). On 28 February 2014, the patient was acutely admitted to the Oncology Department with chest pains, dyspnea and fever. Acute CT did not show progression of disease () but there was diffuse lung infiltration that could have been an infection and there was elevation of CRP. The patient started IV antibiotics but died suddenly while sleeping on 2 March before further investigations revealed a definitive cause of his symptoms. The family refused autopsy, so the exact cause of death could not be determined.

Case 3

An 18-year-old girl presented to the Oncology Department in June 2012 with a large midline tumor involving the base of skull, extending into the brain and involving nasopharynx and ethmoidal sinuses. This girl was treated when she was one year old for bilateral retinoblastoma with radiotherapy to both eyes with two lateral radiation fields (40 Gy). The tumor that was considered to be radiation induced was diagnosed as malignant myofibroblastic sarcoma and was thought to arise from the soft tissue rather than the base of skull. The patient received eight cycles of doxorubicin/ifosfamide with good tumor shrinkage. The tumor was removed surgically in MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA and the pathology showed it to be osteosarcoma. Already in the immediate postoperative period a local recurrence was diagnosed. Standard chemotherapy given in MD Anderson then in Aarhus, Denmark failed to control the disease. The patient then started pazopanib in November 2013 (). Control CT scan () showed marked tumor regression. The patient developed meningitis with staphylococcus bacteria and subarachnoidal hemorrhage in March 2014. The meningitis is believed to be a result of fistulation between nasal cavity and anterior cranial fossa that was revealed on a 3DCT scan after tumor regression. The subarachnoidal hemorrhage could have been a complication of pazobanib. The last scan on 28 March (), after resolution of the meningitis, still showed stable disease and a rim of old bleeding anteriorly (arrow). Pazopanib (ongoing) was paused during the infectious episode. We intend to consider restarting pazopanib in case of disease progression.

Figure 3. A shows the tumor just before the start of pazopanib. B, C shows the response to pazopanib. C also shows subarachnoidal bleeding as a consequence to meningitis (arrow). C shows T2-weighted image because the scan was made in another hospital and there was no sagital T1-weighted images with contrast.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first clinical report that describes response of pazopanib in patients with advanced and progressing metastatic osteosarcomas. The first patient had response for > 3 months but < 6 months, the second patient had response for three months before his sudden death (progression cannot be excluded) and the third patient is still showing response four months after treatment start. Given that at the time of start of pazopanib all patients had evident progressive disease on a CT scan, this is a significant clinical effect. Moreover, the response on images was associated with clear improvement of general condition and, in one case, pain relief.

These results validate the biological rationale of using pazopanib in osteosarcoma patients.

We have observed some of the characteristics seen with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors and anti-angiogenic drugs. In Case 2 stopping pazopanib after an initial treatment for two months was followed by very rapid tumor growth and deterioration of the patient's performance status. Restarting pazopanib led to stabilization of the disease and improved performance. Treatment beyond progression is a known concept for many tyrosine kinase inhibitors and anti-angiogenic drugs [Citation12]. The observation in Case 2 may suggest the validity of this approach in sarcoma patients treated with pazopanib.

Stable disease on CT scans was associated with reduced tumor density as a sign of necrosis. Using choi criteria [Citation13] together with the regular RECIST may therefore be more relevant to judge the effect of pazopanib.

In conclusion, this report suggests that pazopanib can be effective in treating patients with metastatic osteosarcoma and recommend its testing in a large multi-institutional clinical trial.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Luetke A, Meyers PA, Lewis I, Juergens H. Osteosarcoma treatment – Where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40:523–32.

- Tan JZ, Schlicht SM, Powell GJ, Thomas D, Slavin JL, Smith PJ, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management of osteosarcoma – a review of the St Vincent's Hospital experience. Int Semin Surg Oncol 2006;3:38–46.

- Daw NC, Billups CA, Rodriguez-Galindo C, McCarville MB, Rao BN, Cain AM, et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma. Cancer 2006;106:403–12.

- Tabone MD, Kalifa C, Rodary C, Raquin M, Valteau-Couanet D, Lemerle J. Osteosarcoma recurrences in pediatric patients previously treated with intensive chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:2614–20.

- Berrak SG, Pearson M, Berberoğlu S, Ilhan IE, Jaffe N. High-dose ifosfamide in relapsed pediatric osteosarcoma: Therapeutic effects and renal toxicity. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;44:215–9.

- He A, Qi W, Huang Y, Sun Y, Shen Z, Zhao H, et al. Comparison of pirarubicin-based versus gemcitabine- docetaxel chemotherapy for relapsed and refractory osteosarcoma: A single institution experience. Int J Clin Oncol 2013;18:498–505.

- Grignani G, Palmerini E, Dileo P, Asaftei SD, D’Ambrosio L, Pignochino Y, et al. A phase II trial of sorafenib in relapsed and unresectable high-grade osteosarcoma after failure of standard multimodal therapy: An Italian Sarcoma Group study. Ann Oncol 2012;23:508–16.

- Abdeen A, Chou AJ, Healey JH, Khanna C, Osborne TS, Hewitt SM, et al. Correlation between clinical outcome and growth factor pathway expression in osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer 2009;115:5243–50.

- Versleijen-Jonkers YM, Vlenterie M, van de Luijtgaarden AC, van der Graaf WT. Anti-angiogenic therapy, a new player in the field of sarcoma treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2014;2:1–14.

- Tanaka T, Yui Y, Naka N, Wakamatsu T, Yoshioka K, Araki N, et al. Dynamic analysis of lung metastasis by mouse osteosarcoma LM8: VEGF is a candidate for anti-metastasis therapy. Clin Exp Metastasis 2013;30:369–79.

- van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, Kim DW, Bui-Nguyen B, Casali PG, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012;379: 1879–86.

- Kuczynski EA, Sargent DJ, Grothey A, Kerbel RS. Drug rechallenge and treatment beyond progression – implications for drug resistance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:571–87.

- Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria SC, Macapinlac HA, Burgess MA, Patel SR, et al. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: Proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1753–9.