Abstract

Objective To evaluate the safety, local tumor efficacy and relief of symptoms of electrochemotherapy (ECT) treatment in patients affected by recurrence of vulvar cancer (VC), unsuitable for standard treatments.

Methods Ten patients were recruited with histological diagnosis of recurrence of VC. Intravenous bleomycin was injected, after an accurate mapping of all lesions and ECT was performed. Response to therapy was evaluated and quality of life (QoL) was evaluated via questionnaires.

Results Diagnosis stage of primary tumors, according to the FIGO system, was: four patients respectively at stage IB (40%), and at stage II (40%), one patient at stage IIIA (10%), one patient with Paget cancer (10%). Mean age was 76 years (SD ± 7) at time of enrollment. Eight patients (80%) were previously submitted to surgery and/or radio-chemotherapy. Mean treatment time was 20 (range 10–20) min. After a median follow-up of 12 (3–22) months, six patients (60%) were alive.

Conclusions Objective responses (ORs) with local control of the tumor were obtained in 80%. After a mean follow-up of 12 (3–22) months six patients (60%) were alive. The favorable outcome of this study, indicates that ECT is a reliable treatment option that may improve their functioning, thus enhancing the care provided in the palliative setting.

Electroporation-based cancer treatment approaches are currently undergoing intensive investigation in the field of drug delivery of several novel tumor targeting. The first biomedical application of this method of treating cancer came in the form of electrochemotherapy (ECT), which, since its beginnings in the late 1980s, has evolved into a clinically verified treatment approach for cutaneous and subcutaneous tumor nodules [Citation1]. Cutaneous metastases from solid tumors account for 0.7% to 9% of all metastases [Citation2]. Besides their dismal prognostic value, they can be a distressing problem for patients. Cutaneous metastases may cause considerable discomfort as a consequence of ulceration, oozing, bleeding and pain. Oncologists can choose among several different options depending on patient’s status and disease spread, exclusively superficial versus superficial plus visceral. In some cases, patients may have stable disease in sites other than the skin, and clinicians may be reluctant to use systemic chemotherapy for the skin metastases alone. Recently, ECT has been proposed as a novel, complementary therapeutic weapon for the control of superficial disease [Citation3–5]. ECT is an effective local tumor ablation modality in the treatment of solid cancers, which combines the administration of no permeable or poorly permeable cytotoxic drugs with the application of electric pulses to the tumors to facilitate the drug delivery into the cancer cells. ECT uses local application of short duration, electric pulses directly to the tumor cells via an electrode, causing destabilization of the cell membrane and thereby making it transiently permeable

Currently, the tumors most frequently treated with ECT are melanoma and breast cancer metastasis, but also head and neck cancer, primary tumors of the skin, and Kaposi sarcoma. At present, ECT constitutes an additional therapeutic tool in selected patients, refractory/relapsed after conventional therapies, which is able to provide relief from cutaneous metastases that hold psychological and physiological strain for the patient, thus improving the patient’s quality of life (QoL).

Although the treatment of smaller lesions results in higher complete response (CR) rates, ECT has also proven to be effective in palliation of symptomatic lesions and as a neoadjuvant treatment to allow for less invasive surgical approaches [Citation6], due to the low toxicity of the treatment used on patients with poor performance status, with important comorbidities, which may render them unsuitable for surgery. The majority of patients had no or mild pain after ECT. Patients at risk for post-procedure pain could be identified at the pre-treatment visit, and/or at the time of treatment, enabling a pain management strategy for this group [Citation7]. The aim of this preliminary study was to evaluate the safety, local efficacy, acceptability and QoL of ECT with bleomycin in reducing the size of tumors in patients with vulvar carcinoma with loco-regional cutaneous recurrence submitted to multiple previous treatments (chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery) and unsuitable for standard treatments. In addition, the response duration and the impact of ECT on disease-related symptoms and patients’ functioning in everyday life were considered. Also the relationship between tumor size and effectiveness of an ECT was evaluated. This prospective analysis is intended as an update on the therapy to improve possible future developments.

Material and methods

Between January 2013 and December 2014, 11 patients were recruited with histological diagnosis of single or multiple loco-regional recurrences of cutaneous recurrences of vulvar cancer and were eligible for the study according to the inclusion criteria.

One patient was lost during the follow-up therefore was excluded from the study. The cases consisted in nine recurrences of cutaneous vulvar cancer, and one case of primitive Paget tumor of the vulva.

Patients were unsuitable for standard treatments because of tumor characteristics (previous multiple surgeries or previous radiotherapy) and general status and were invited to participate to the study: 60% performed palliative treatment and 40% of the cases underwent to therapeutic management with ECT. The inclusion criteria and the technical procedure were derived from the European Standard Operating Procedures of Electrochemotherapy (ESOPE) [Citation3]: patients were to have measurable tumor nodules suitable for electrode application and a performance status, according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale.

Exclusion criteria included serious lung, heart, or liver disease, epilepsy, short life expectancy (<3 months), active infection, previous treatment with bleomycin to maximal dosage, and different anticancer therapies administered within two weeks before ECT. The only deviance from that protocol was the inclusion of tumor nodules also >3 cm in size. Cefazolin 2 g intravenous and anti-thrombotic prophylaxis was performed; patients received oral fluids and a solid diet 12 hours after anesthesia.

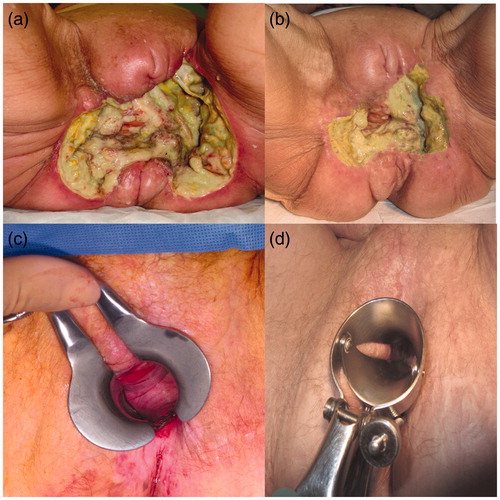

Bleomycin (Bleomycin Nippon vials, 15 mg, Sanofi- Aventis) was preferred to cisplatin because of the high number of patient tumor nodules and the drug’s favorable toxicity profile. It was administered intravenously (15 000 UI/m2= 15 U/m2 which is approximately equal to 8.5 mg/m2, in a bolus lasting 60–90 seconds). Electric pulses were delivered by means of two types of needle electrodes (parallel arrays finger and hexagonal arrays N-10-HG-10 mm, suitable for bigger tumors) [Citation8] connected to an electroporator device. Electrical pulses started eight minutes after bolus. Pulse delivery frequency was 5 kHz (duration of 100 μs). Electrodes were gently inserted into the skin of the area affected at a depth of 1 cm; the procedure was repeated progressively covering all of the area to be treated.

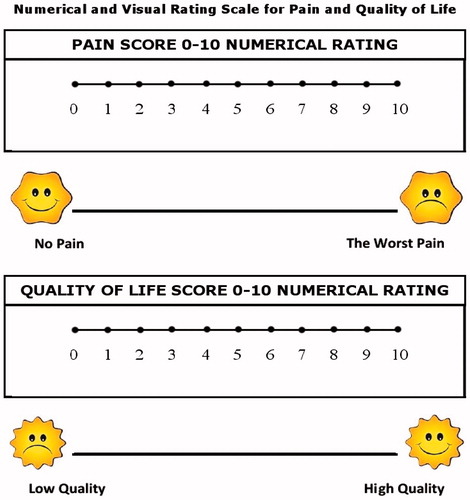

If required, a second run was delivered or the electrode repositioned until complete tumor electroporation was obtained. Visual analog score (VAS) for pain and vulvar cancer subscale (VCS) part of functional assessment of vulvar cancer therapy (FACT-V) for QoL [Citation9], were administered before and four weeks after the procedure to evaluate an improvement in QoL (). Digital mapping of all lesions was performed and the area involved was sketched. All nodules were measured and if multiple nodules were present, the area was the sum of the area of each lesion.

A full clinical history, clinical examination, routine blood biochemistry, computed tomography (CT) scan and 18 F-FDG-PET/CT to evaluate distant metastasis were required.

Willingness to undergo further ECT treatment, if necessary, was asked to patients. ECT response criteria was defined according to the WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment [Citation10]: CR when the tumor nodule was disappeared and not palpable; partial response (PR) as a decrease of at least 50% in the products of the two largest perpendicular diameters of the tumor (corresponding to tumor area); progressive disease (PD) when the tumor size had increased by more than 25%. In all other cases, a response was determined as no change. Tumor response was determined not earlier than four weeks post-treatment by two observations not less than four weeks apart. All continuous data are expressed in terms of mean and standard deviation of the mean and range. Paired t-test was performed to investigate response to VCS before and after ECT. A p < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using statistical software from SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA).

Results

Diagnosis stage of primary tumors, according to the FIGO system, was: four patients respectively at stage IB (40%), and at stage II (40%), one patient at stage IIIA (10%), one patient with Paget cancer (10%).

Median age was 68 years (range 59–84) at time of enrollment. Eight patients (80%) were previously submitted to surgery and/or radio-chemotherapy and the mean time to relapse after last treatment was 36 (SD ± 14 months).

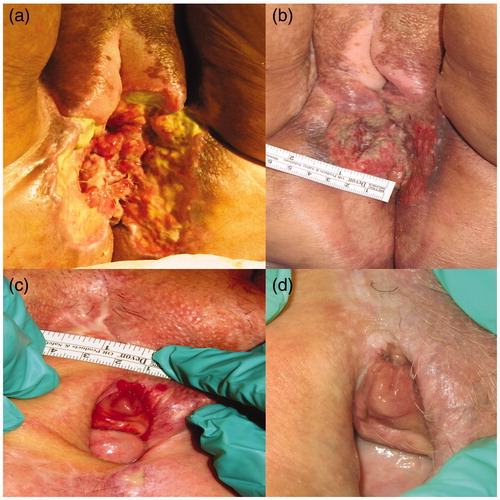

Mean time of ECT was 20 (range 10–20) min. After a median follow-up of 12 (range 3–22) months six patients (60%) were alive. One patient was free from disease at 16 months follow-up. Four patients died because of systemic disease progression (three IIB, one IIIA). In one case (stage IIB) of four deaths, the patient had performed two ECT palliative treatments, the second treatment after one month due to ulcerated perineum () and she died after 19 months from the first ECT. In 60% of cases, two cycles of ECT were performed. In 20% were performed three cycles, in 20% two cycles. In two cases (20%), there was no change in tumor size at the time of follow-up after four months. No complications occurred. Some patients underwent up to three treatments because of new lesions, but maintained superficial tumor control. After a median follow-up of 12 (Citation3–22) months, only one patient experienced relapse in the treatment field, localized in the same treated site. Mapping of the lesions showed that disease was present in the vulva in 100% of cases. Multiple lesions were present in four patients (40%). Lesion characteristics are shown in .

Figure 2. Pre- and post-palliative treatment for ulcerated peritoneum (STAGE IIB) (a, b) and complete response for Paget (c; d).

Table I. Patients’ characteristics.

Post-operatively patients did not experience local pain, fever or nausea; we evaluated the response to the therapy after one month and we observed: CR in two patients (20%), PR in four patients (40%), NC in two patient (20%), and PD in two patients (20%). In patients with CR the nodule disappeared and the residual skin was pale and soft and regular (). One patient was free from disease at the time of follow-up. Objective responses (ORs) with local control of the tumor were obtained in 80%. After a mean follow-up of 12 (Citation3–22) months six patients (60%) were alive. Two patients with CR relapsed after four and seven months and were candidates for further treatment with ECT. One patient with PD for age and poor performance status was not submitted to other treatments and was supported by palliative cure.

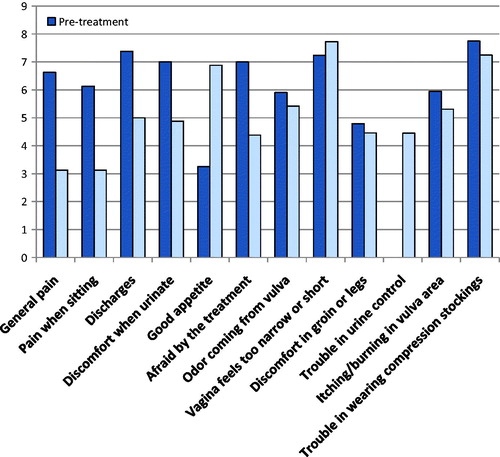

Evaluation of VAS and VCS performed one month after treatment showed a significant reduction in pain (p = 0.03) and a significant reduction in oozing, odor and urinary discomfort ( and ).

Discussion

Preclinical developments before the use of ECT helped to define its mechanism of action, the most effective treatment parameters, both electrical and pharmacological, for safe and reproducible treatments. The first study phase I/II [Citation1] showed antitumor effectiveness of ORs were obtained in 72% of nodules; CR was obtained in 57% of the treated nodules. ECT has been shown to be highly effective in providing local tumor control and palliation of symptomatic lesions located in cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues regardless of their histological origin, while maintaining a very low toxicity profile and high patient acceptance [Citation3,Citation11–13].

This loco-regional therapy that combines low-dose cytotoxic drugs (bleomcyn and cisplatin), administered intravenously or intra-lesionally, and high intensity electric pulses to induce electroporation to improve drug delivery into tumor cells [Citation14].

It can successfully destroy superficial metastases from different tumor types, and its limited toxicity, even on areas otherwise requiring disfiguring resections, can permit a combination with other anticancer therapies. However, when surgery cannot be performed with a reasonable cosmetic and functional outcome, other options must be evaluated.

To facilitate the diffusion of bleomycin through the cell membrane, local electropermeabilization of cells can be used; the physical changes induced in the cell membrane enable diffusion of bleomycin into the cell, direct access to the cytosol, and transport to the nucleus, in which it exerts its cytotoxic activity. In high concentrations, such as those achieved with ECT, bleomycin can cause cell death within a few minutes. Preclinical studies have demonstrated a 300- to 700-fold increase in bleomycin cytotoxicity using this method of drug delivery [Citation15–17]. In addition to drug-induced cell killing, electroporation is responsible for a variety of vascular changes in the tumor region. It produces a reflex constriction of vessels induced by electric pulses, which is responsible for a temporary reduction in perfusion of tumor tissue and enables prolonged exposure of tumor cells to the drug. Further vascular effects exerted by ECT include endothelial cell apoptosis and neovascular reorganization due to a local reduction in the production of angiogenic factors. Finally, an immune response seems to be involved in the therapeutic effect of ECT, as massive destruction of tumor cells by the treatment may release tumor-associated antigens, both locally (at the site of electroporation) and systemically, thus raising a systemic immune response [Citation18].

Among several drugs tested in preclinical studies, bleomycin and cisplatin have been found to be the most suitable agents for ECT [Citation19]. Drug administration could be performed intravenously for bleomycin, dosed accordingly to the patient body surface area, or intratumorally for bleomycin and cisplatin, dosed accordingly to the tumor volume. The efficacy of ECT on local control of superficial lesions has been well established. In addition, early clinical evidence supports investigation of ECT application beyond the skin to visceral metastases. In the longer term, the association of ECT with appropriate immunomodulant stimuli holds promise for the translation of local disease control to a systemic response mediated by the patient’s immune system. In a palliative setting, ECT proved to be safe, effective in all tumors treated, and useful in preserving patients’ QoL.

ECT has attracted recent attention thanks to the work supported by the EU Commission that led to the development of a new device, the Cliniporator (IGEA, Modena, Italy), which simplifies the procedure. Furthermore, the European Standard Operating Procedures on the ECT (ESOPE) project has favored the standardization of this treatment, thus providing the information necessary for the spread of the use of ECT in the clinical practice. The ESOPE study recruited 41 patients with cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules <3 cm in size. ECT proved to be effective both in melanoma and non-melanoma tumor nodules with a CR in 74% of tumors, a PR in 11%, and no change in 10% according to World Health Organization criteria; local tumor control rate was 73% to 88% at five months after the treatment. The results of analysis based on data from 1466 tumors of any histotype show significantly lower effectiveness of ECT on tumors with maximal diameter equal to or larger than 3 cm CR of 33.3%, OR of 68.2% in comparison to smaller tumors (CR% of 59.5%, OR% of 85.7%). The results of meta-analysis indicated that ECT performed on tumors smaller than 3 cm statistically significantly increases the probability of CR by 31.0% and OR by 24.9% on average in comparison to larger tumors. The analysis of raw data about the size and response of tumors showed statistically significant decrease in effectiveness of ECT progressively with increasing tumor diameter [Citation20,Citation21]. Partial responders and new lesions can be handled with additional ECT albeit increasing local pain and skin toxicity [Citation22]. Sufficiently high electric field in the tumor tissue can be assured by delivery of pulses of adequately high voltage and appropriate positioning of the electrodes. In addition, some other conditions or parameters could be relevant, such as patient and tumor (histotype, size and location) characteristics and treatment parameters (drug, dose and route of administration, electrode type, protocol and timing of pulse delivery). No serious adverse events (SAE) were observed.

In our series the total VCS score showed a significantly better QoL after treatment (, ). All patients were sexually inactive and did not respond to sexual questions. All patients confirmed that the procedure could be repeated. Our study showed that ECT was very acceptable even in elderly patients and all patients tolerated the treatment well. ECT treatment has been confirmed to be an effective and well tolerated treatment modality for the local control of unresectable and/or refractory superficially disseminated cancer in patients who are not suitable for standard oncological therapies [Citation23]. In 60% of our cases, two cycles of ECT were performed.

Table II. Quality of life (FACT-V) and pain (VAS) questionnaires.

Our results, in concordance with previous studies [Citation24,Citation25], suggest that ECT is an efficient and simple treatment that may improve QoL in patients with metastatic disease and clinicians should not hesitate to use it even for elderly patients. The main advantages of ECT include a high response rate, durable local tumor control and limited toxicity to healthy surrounding tissues. These favorable outcomes, coupled with the simplicity of ECT administration, rapid patient recovery and encouraging toxicity reports, make this procedure a useful treatment option, alone or in combination with other treatments. In palliative setting, in patients with advanced disease, the effective control of superficial metastases by ECT may contribute to the preservation of the patient’s QoL. ECT treatment has been confirmed to be an effective and well tolerated treatment modality for the local control of unresectable and/or refractory superficially disseminated melanoma in patients who are not suitable for standard oncological therapies. The absence of systemic side effects and the low impact on the immune system also make this treatment suitable for elderly people, even with repeated courses [Citation26].

Conclusion

The favorable outcome obtained in this study, indicates that ECT is a reliable treatment option that may improve their functioning, thus enhancing the care provided in the palliative setting. The benefit obtained in terms of QoL, although preliminary, should be regarded as a considerable result and needs further studies due to the missing data in literature. ECT ensures good tissue preservation as a result of the intrinsic physical characteristics of tumor tissue and the geometrical conformation of electrodes applied. This therapeutic approach is a feasible alternative in case of inoperable tumors, located in pre-irradiated areas and resistant to chemotherapy. There are a number of potential benefits to the use ECT in the palliative setting: tissue preservation, brief hospitalization, repeatability, and favorable cost benefit ratio.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Belehradek M, Domenge C, Luboinski B, Orlowski S, Belehradek J, JrJr., Mir LM. Electrochemotherapy, a new antitumour treatment: first clinical phase I-II trial. Cancer 1993;72:3694–700.

- Rolz-Cruz G, Kim CC. Tumor invasion of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:89–102.

- Marty M, Sersa G, Garbay JR, Gehl J, Collins CG, Snoj M, et al. Electrochemotherapy. An easy, highly effective and safe treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases: results of ESOPE study. EJC Suppl. 2006;4:3–13.

- Rols MP, Bachaud JM, Giraud P, Chevreau C, Roché H, Teissié J. Electrochemotherapy of cutaneous metastases in malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2000;10:468–74.

- Giardino R, Fini M, Bonazzi V, Cadossi R, Nicolini A, Carpi A. Electrochemotherapy a novel approach to the treatment of metastatic nodules on the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Biomed Pharmacol. 2006;60:458–62.

- Gargiulo M, Moio M, Monda G, Parascandolo S, Cubicciotti G. Electrochemotherapy: actual considerations and clinical experience in head and neck cancers. Ann Surg 2010;251:773

- Quaglino P, Matthiessen LW, Curatolo P, Muir T, Bertino G, Kunte C, et al. Predicting patients at risk for pain associated with electrochemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:298–306.

- Sersa G, Miklavcic D, Cemazar M, Rudolf Z, Pucihar G, Snoj M. Electrochemotherapy in treatment of tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008;34:232–40.

- Obermair MJ, Cella A, Perin D, Nicklin LC, Ward JL. BG, et al. The functional assessment of cancer-vulvar: reliability and validity. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:568–75.

- WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatments, vol. 48; 1997; 22–7.

- Glass LF, Pepine ML, Fenske NA, Jaroszeski M, Reintgen DS, Heller R. Bleomycin-mediated electrochemotherapy of metastatic melanoma. Arch Dermatol 1996;132:1353–7.

- Sersa G, Stabuc B, Cemazar M, Jancar B, Miklavcic D, Rudolf Z. Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin: potentiation of local cisplatin antitumour effectiveness by application of electric pulses in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 1998;34:1213–18.

- Sersa G. The state of the art of electrochemotherapy before ESOPE study. Advantages and clinical use. Ejc 2006;4:S52–9.

- Testori A, Tosti G, Martinoli C, Spadola G, Cataldo F, Verrecchia F, et al. Electrochemotherapy for cutaneous and subcutaneous tumor lesions: a novel therapeutic approach. Dermatol Ther 2010;23:651–61.

- Gehl J, Skovsgaard T, Mir LM. Enhancement of cytotoxicity by electropermeabilization: an improved method for screening drugs. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9:319–25.

- Orlowski S, Belehradek J, JrJr, Paoletti C, Mir LM. Transient electropermeabilization of cells in culture. Increase of the cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:4727–33.

- Tounekti O, Pron G, Belehradek J, Mir LM. Bleomycin, an apoptosis-mimetic drug that induces two types of cell death depending on the number of molecules internalized. Cancer Res 1993;53:5462–9.

- Campana LG, Testori A, Mozzillo N, Rossi CR. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with electrochemotherapy. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:301–7.

- Mir LM, Orlowski S. Mechanisms of electrochemotherapy. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1999;35:107–18.

- Mali B, Miklavcic D, Campana LG, Cemazar M, Sersa G, Snoj M, et al. Tumor size and effectiveness of electrochemotherapy. Radiol Oncol. 2013;47:32–41.

- Matthiessen LW, Chalmers RL, Sainsbury DC, Veeramani S, Kessell G, Humphreys AC, et al. Management of cutaneous metastases using electrochemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:621–9.

- Campana LG, Valpione S, Falci C, Mocellin S, Basso M, Corti L, et al. The activity and safety of electrochemotherapy in persistent chest wall recurrence from breast cancer after mastectomy: a phase-II study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:1169–78.

- Quaglino P, Mortera C, Osella-Abate S, Barberis M, Illengo M, Rissone M, et al. Electrochemotherapy with intravenous bleomycin in the local treatment of skin melanoma metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15: 2215–22.

- Perrone AM, Cima S, Pozzati F, Frakulli R, Cammelli S, Tesei M, et al. Palliative electro-chemotherapy in elderly patients with vulvar cancer: A phase II trial. J Surg Oncol. 2015;Dec;112:529–32. doi: 10.1002/jso.24036. Epub 2015 Sep 8.

- Perrone AM, Galuppi A, Cima S, Pozzati F, Arcelli A, Cortesi A, et al. Electrochemotherapy can be used as palliative treatment in patients with repeated loco-regional recurrence of squamous vulvar cancer: a preliminary study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Sep;130:550–3.

- Curatolo P, Quaglino P, Marenco F, Mancini M, Nardò T, Mortera C, et al. Electrochemotherapy in the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma cutaneous lesions: a two-center prospective phase II trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:192–8.