Abstract

Background This study examined employment patterns and associated factors in lymphoma survivors treated with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT-ASCT) from diagnosis to a follow-up survey at a mean of 10 years after HDT-ASCT.

Patients and methods All lymphoma survivors aged ≥18 years at HDT-ASCT in Norway from 1987 to 2008, and alive at the end of 2011 were eligible for this cross-sectional study performed in 2012/2013. Participants completed a mailed questionnaire. Job status was dichotomized as either employed (paid work) or not-employed (disability and retirement pension, on economic support, home-makers, or students).

Results The response rate was 78%, and the sample (N = 312) contained 60% men. Mean age at HDT-ASCT was 44.3 and at survey 54.0 years. At diagnosis 85% of survivors were employed, 77% before and 77% after HDT-ASCT, and 58% at follow-up. Forty seven percent of the survivors were employed at all time points. The not-employed group at survey was significantly older and included significantly more females than the employed group. No significant between-group differences were observed for lymphoma-related variables. Fatigue, mental distress and type D personality were significantly higher among those not-employed, while quality of life was significantly lower compared to the employed group. Older age at survey, being female, work ability and presence of type D personality remained significantly related to being not-employed at survey in the multivariable analysis.

Conclusions Our findings show that not-employed long-term survivors after HDT-ASCT for lymphoma have more comorbidity, cognitive problems and higher levels of anxiety/depression than employed survivors. These factors should be checked and eventually treated in order to improve work ability.

Over the last 2–3 decades high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT-ASCT) has become an established therapeutic option for many types of lymphoma [Citation1]. The indications have expanded and changed over time, and despite improvements in first-line therapy for most lymphoma types, HDT-ASCT still is an important and frequently used treatment option [Citation2]. However, HDT-ASCT represents a physical and mental strain for the patients, and can be a considerable challenge for the patients’ work ability.

Most lymphomas considered for HDT-ASCT are diagnosed when the patients are within 18–67 years (working age), and the patterns of employment during their treatment trajectories are important outcomes both for patients, their families and for society. Within this field, however, studies of such patterns of HDT-ASCT survivors have been heterogeneous as to type of malignancies and/or treatment modalities [Citation3,Citation4].

Factors from many areas influence employment status after cancer treatment. Although they have been most extensively studied in breast cancer [Citation5], these areas are relevant for patients with lymphomas. Socio-demographic factors are: sex, age, level of education, relationship status, income, and social support. Cancer-related factors are: cancer type and stage, physical fitness, comorbidities, self-rated health, and adverse effects like fatigue or pain. Treatment-related factors are chemotherapy, surgery, hormone therapy, and HDT-ASCT. Psychological factors are: levels of depression, anxiety, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), cognitive problems and personality traits. Work-related factors are: Labor market issues, work ability, type of job, working time, salary, job flexibility, and level of support from colleagues and leaders. Any study of employment patterns of cancer patients should include factors from all these areas.

This study explores the employment patterns of lymphoma patients from before diagnosis through HDT-ASCT and to a follow-up survey at a mean of 10 years after that treatment. We posed two research questions: 1) What are the employment patterns from before diagnosis, before and after HDT-ASCT, and at follow-up? and 2) What factors from the areas of socio-demography, psychology, cancer and treatment, and work are significantly associated with unemployment at the follow-up survey?

Materials and methods

Patients

The patients were identified through treatment records and registries at the four oncological departments of the Norwegian university hospitals in Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim and Tromsø. The patients were also cross-checked against reports from HDT-ASCT meetings, the clinical quality registry for lymphomas at Oslo University Hospital and radiotherapy registers.

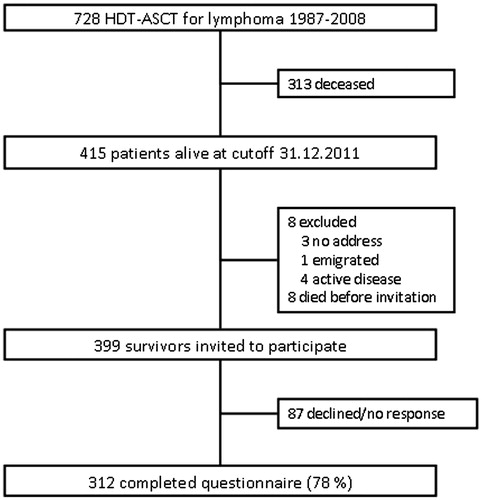

All 415 lymphoma survivors aged ≥18 years at treatment with HDT-ASCT in Norway from 1987 to 2008 and alive at 31 December 2011 were eligible for this cross-sectional follow-up study performed in 2012/2013. One survivor was excluded due to emigration and four due to current systemic therapy for lymphoma. Another eight survivors died before they were invited, and three survivors were untraceable due to lack of official home address, leaving 399 patients contacted with a mailed questionnaire. Among them 312 returned the questionnaire (78% response rate) (Flowchart in ).

Treatment

The treatment for lymphomas in Norway has followed national and international guidelines [Citation2,Citation6]. The high-dose regimen consisted of total body irradiation (TBI) and high-dose cyclophosphamide from 1987 to 1996 and BEAM-chemotherapy (BCNU, etoposide, cytarabin and melphalan) only from 1996 [Citation2,Citation6].

Main outcome

Employment status was self-rated and dichotomized as employed (in paid work or currently on sick-leave which requires paid work status according to Norwegian social security regulations) or not-employed (on disability or retirement pension, supported while being unemployed or on rehabilitation, home-makers, or students).

Cancer-related variables

Details on lymphoma-related variables were retrieved from the patient charts. Based on primary diagnosis the patients were divided into three groups: Hodgkin lymphoma, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas (diffuse large B cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma and T cell lymphomas), and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas (mostly follicular lymphoma). Time periods for HDT-ASCT was divided into three: 1987–1995, 1996–2002, and 2003–2008. Lymphoma stages at diagnosis were dichotomized into Ann Arbor stage I and II versus III and IV. Second cancer concerned later identification of any other malignancy than the primary lymphoma.

Somatic comorbidity was present if the patients reported one or more of stroke, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, heart failure, hypertension, asthma/chronic bronchitis, diabetes, gastric ulcer, diseases of the kidney, liver, thyroid, joints, or the blood system.

Psychological variables

Fatigue Questionnaire (FQ). The FQ covers the last four weeks and contains 11 items concerning mental and physical fatigue rated from 0 (as before) to 3 (very much more). The physical fatigue score ranges from 0 to 21, the mental from 0 to 12, and the total fatigue score from 0 to 33 with higher scores implying more fatigue [Citation7,Citation8]. The internal consistencies showed Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of 0.92 for total fatigue, 0.93 for physical fatigue, and 0.80 for mental fatigue.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS concerns anxiety and depression last week and consists of seven items each on the anxiety and depression sub-scales. The item scores range from 0 (not present) to 3 (highly present), so the sub-scale scores range from 0 (low) to 21 (high) [Citation9]. The internal consistency was alpha 0.82 for the depression and 0.87 for the anxiety subscales.

Short Form 36 (SF-36). The SF-36 assesses eight dimensions (four physical and four mental) of generic HRQoL. Based on converting algorithms poorest HRQoL is 0 and best is 100. The physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) composite scales are T-transformed and have a mean of 50 in the Norwegian population [Citation10,Citation11].

Type D personality scale (DS14). The DS14 covers two personality traits; negative affectivity (NA) and social inhibition (SI) with seven items each. The scoring of the items is on five point Likert scales from 0 (false) to 4 (true), giving the NA and SI ranges from 0 to 28. Caseness of NA and SI is present with a sum score ≥10, and scores above both these cutoffs must be present to identify a case of type D personality [Citation12,Citation13]. The internal consistency was 0.90 for NA and 0.87 for SI.

Cognitive problems last week concerned those who rated that they had “much” or “very much” problems with either concentration or memory versus those with “none” or “some”.

Socio-demographic variables

Besides sex and age, paired relationship was defined as those married or cohabiting, and level of education was dichotomized into low (≤12 years) or high (>12 years). Expected gross family income during the year of the survey was dichotomized as below (low income) or above (high income) 600 000 Norwegian crowns.

Work-related variables

From the Work Ability Index (WAI) we included current work ability before diagnosis and at survey compared to the best ability ever on a VAS scale from 0 (complete inability to work) to 10 (work ability at its best). Change of work ability was the mean difference between the scores at these time points. Work ability in relation to physical and mental demands of the work was rated from “very poor” to “very good”, and poor work ability covered the ratings of “very poor” and “poor” at diagnosis and at survey [Citation14]. Whether the lymphoma was the main reason for change of work place, occupation, unemployment, or change of work task, was recoded as yes or no.

Statistical considerations

Between-group comparisons of continuous variables were done with t-tests, and in case of skewed distributions Mann-Whitney U-tests were used. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed with χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. The internal consistencies of instruments were examined with Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Adjustments between-group differences of age at survey, sex and level of education were performed with multivariable linear (continuous dependent variables) or logistic (dichotomized dependent variables) regression analyses. The strength of associations in logistic regression was expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals as appropriate (95% CI). Variables included in multivariable analyses were tested for multicollinearity, and due the size of the not-employed group (N = 102), only 10 variables were entered into that analysis. We included the variables that we considered as most relevant clinically. The p-value was set as <0.05, and all tests were two-sided. The statistical software applied was PASW version 20 for PC (IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA).

Ethical considerations

The Regional Committee for Medicine and Health Research Ethics of South-East Norway approved the study. All patients returning questionnaires gave written informed consent.

Results

Attrition analysis

The 312 participants were older at survey compared to the 87 non-participants (mean 54.0 vs. 50.7 years, p = 0.024). There was no significant difference between the participants and non-participants regarding sex, age at diagnosis or at HDT-ASCT, or observation time from HDT-ASCT to survey.

Total sample characteristics

The total sample at survey (N = 312) consisted of 187 (60%) men and 125 (40%) women. Mean age at diagnosis was 41.5 years (SD 13.5), at HDT-ASCT 44.3 (SD 13.6) and at survey 54.0 years (SD 11.3). Mean time from diagnosis to survey was 12.4 years (SD 6.1) and from HDT-ASCT to survey 9.7 years (SD 5.1).

Proportions and patterns of employment over time

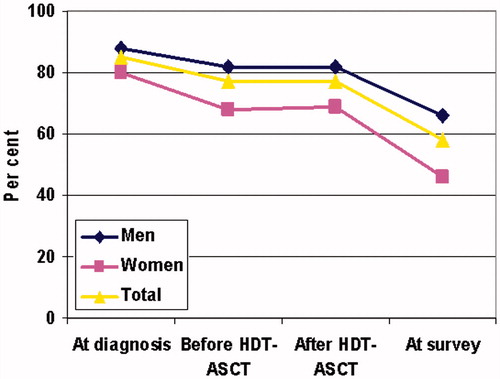

Among the 312 survivors included, 265 (85%) were employed at diagnosis, 239 (77%) before HDT-ASCT, 240 (77%) after HDT-ASCT, and 179 (58%) at follow-up survey. The reduction of survivors being employed from diagnosis to before and after HDT-ASCT was significant (p = 0.02), and so was the reduction from after HDT-ASCT to survey (p < 0.001). The proportion of men being employed was significantly higher than for women both before and after HDT-ASCT, and at survey ().

Figure 2. Proportions of employed patients over time according to sex and total sample (N = 312)*.

*The difference between men and women are p < 0.007 before and after HDT-ASCT and at survey. HDT-ASCT: high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation.

In the total sample, 13 patterns of employment over time were observed (). A total of 47% of the survivors were employed at all time points, while 15% were employed after HDT-ASCT but not at the survey, and 11% were employed before HDT-ASCT, but not later. Ten other employment patterns were identified together representing 26% of the survivors. Forty-six patients (15%) moved from not-employed to employed status at some time during the time from diagnosis to survey, while 76 patients (24%) moved from employed to not-employed status during the same time period.

Table 1. Patterns of employment (E) and not-employment (N) over time (N=312).

At survey, 60 survivors (19%) were on disability pension and 45 (14%) were retired due to high age. However, in Norway if motivated survivors on these pensions are allowed to hold part-time jobs, and 74 (70%) of these 105 survivors did so.

Employment versus not-employment groups at survey

Focusing on employment at survey, we omitted 31 patients who had retired completely, leaving 281 patients for examination at survey. Among them, 179 patients (64%, 95% CI 58–69%) were employed and 102 (36%, 95% CI 31–42%) were not-employed. Comparing these two groups the following significant between-group differences were observed ().

Table 2. Demographic and disease characteristics of the sample according to work status at follow-up survey (N = 281).

Socio-demography

At diagnosis, HDT-ASCT and survey, those employed were significantly younger than those not-employed. The employed group also included significantly more males, had a higher proportion with high level of education and high family income. Lymhoma-related variables showed no significant between-group differences except for lower proportion of comorbidity in the employed group. Work-related variables: Mean work ability was higher in the employed group both at diagnosis and at survey, and the proportions with poor physical or mental work ability and work changes due to lymphoma were significantly lower in that group compared to the not-employed group. The reduction in mean work ability from diagnosis to survey was significantly greater in the not-employed group.

Psychological variables

The means of the fatigue scores were all significantly higher in the not-employed group compared to the employed one (). All SF-36 dimensions mean scores were significantly lower and the HADS anxiety and depression mean scores were significantly higher in the not-employed group. The proportions of type D personality and of cognitive problems were significantly higher in the not-employed group.

Table 3. Fatigue, quality of life, mental problems and lifestyle of the sample according to employment status at follow-up survey (N = 281).

The significant findings in and were confirmed in univariate logistic regression analyses (), and older age at survey, being female, reduced work ability at survey, and presence of type D personality remained significantly associated with not-employed status in the multivariable analysis.

Table 4. Logistic regression analyses of independent variables and being currently unemployed (N = 102) with employed (N = 179) as reference.

Discussion

Main findings

In our total sample, 85% of the lymphoma survivors were employed at diagnosis, 77% before and 77% after HDT-ASCT, and at survey at a mean of 9.7 years later 58% of the survivors were employed. In 2012 in the age group of 50–54 years (mean age of our sample was 52.3 years) 85.5% of Norwegian males and 82.2% of females were employed, and the proportion of 58% in our sample is significantly lower. Investigating patterns of employment, 47% of the survivors were employed at all time points, while 11% were employed before HDT-ASCT, and 15% were employed after HDT-ASCT but not until the survey.

The not-employed group at survey was significantly older showed lower work ability, included more females and patients with type D personality than the employed group in multivariable analysis. No significant between-group differences were observed for lymphoma-related variables. Levels of fatigue, anxiety, and depression, as well as proportions of comorbidity and cognitive problems were significantly higher among those not-employed, and HRQoL was significantly lower compared to the employed group.

Relation to previous studies

From Denmark Horsboel et al. reported that at a median of six years since diagnosis and without specification of treatment, 9% of Hodgkin lymphoma survivors were on disability pension, 15% of survivors after treatment for diffuse large B cell lymphomas, and 17% after follicular lymphomas [Citation15]. These proportions are similar to 19% on disability pension observed by us for all types of lymphomas at a mean follow-up of 12.5 years since diagnosis. In another study Horsboel et al. [Citation4] found that 89% of Hodgkin lymphoma survivors returned to employment, while the proportions were 74% for survivors of diffuse large B cell lymphoma, and 72% for follicular lymphoma. These proportions of return to employment are comparable with ours.

Interestingly, Abrahamsen et al. [Citation16] followed a Norwegian sample of 459 Hodgkin lymphoma survivors treated between 1971 and 1991 with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy but no HDT-ASCT. At a mean of 12 years after diagnosis 76% of the Hodgkin lymphoma survivors were employed, 21% were not-employed, and 19% on disability pension. They did not focus on sex differences although 85% of men and 64% of women were employed at follow-up (p < 0.001). They observed that older age, and high levels of depression and fatigue were significantly associated not-employed status, which is in accordance with our findings of associated factors.

Higher proportion of females in the not-employed group has also been observed among Norwegian breast cancer survivors compared to male survivors of testicular and prostate cancer [Citation17]. An explanation for this finding could be the high proportion of Norwegian women in part-time jobs (42%), which are difficult to keep up in with reduced work ability after cancer and its treatment.

Other findings

Interestingly none of the lymphoma-related variables except older age at diagnosis and at HDT-ASCT, were associated with not-employed status at survey. Not-employed status was significantly associated with physical and mental fatigue, all physical and mental dimensions of HRQoL, higher anxiety, depression, and comorbidity. All these factors have previously been identified with reemployment after various types of cancer.

In our sample the proportion of type D personality was 27%, while in a study from the Netherlands, Mols et al. [Citation18] reported 17% (p = 0.03). This difference may be due to sampling differences, but another explanation could be the significant differences in time since diagnosis (mean 4.5 years in their sample and 12.5 years in ours). Anyway, presence of a personality style characterized by negative affects and social inhibition is significantly associated with being not-employed.

Cognitive problems have increasingly been identified as a factor related to not-employment in various groups of cancer survivors [Citation19]. This was confirmed in our study. Such problems could reduce the mental part of work ability, which also was confirmed in our study. Among both employed and not-employed the work ability mean score was significantly reduced from diagnosis to survey, even if age was adjusted for (data not shown).

Some clinical implications as for helping survivors to stay employed particularly concerning female survivors can be based on our findings. Comorbidity, cognitive complaints, fatigue, anxiety and depression should be identified and treated according to accepted recommendations.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of our study is that it is based on a representative national sample. The other is the high response rate of 78% at a mean of 12.5 years after diagnosis. The attrition analysis showed that younger survivors are under-represented in our sample, implying that our rates of employment may be lower than found in the general Norwegian population of lymphoma survivors treated with HDT-ASCT. Limitations to consider are that all work-related data were collected by questionnaire at one time point with a risk for recall bias and not controlled by interviews and/or data from The Norwegian Work and Welfare Administration. Much information from the patients was collected retrospectively with the risk of recall bias. Our cross-sectional design did not allow for causal links only for associations. We did a high number of comparisons with an increased risk of spurious significant associations.

Conclusions

In this national study of Norwegian lymphoma survivors treated with HDT-ASCT, 85% of the survivors were employed at diagnosis and 58% at a mean of 10 years after HDT-ASCT. Forty-seven percent were employed all the time from diagnosis to the follow-up survey. Mainly psychosocial variables and hardly any lymphoma-related variables were associated with not-employed status at follow-up. At that time older age, female sex, poor work ability, and presence of type D personality were the variables significantly associated with not-employed status in multivariable analyses.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Ljungman P, Bregni M, Brune M, Cornelissen J, de WT, Dini G, et al. Allogeneic and autologous transplantation for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: current practice in Europe 2009. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:1219–34.

- Smeland KB, Kiserud CE, Lauritzsen GF, Blystad AK, Fagerli UM, Fluge O, et al. High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell support for lymphoma in Norway 1987-2008 3. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen 2013;133:1704–9.

- Hensel M, Egerer G, Schneeweiss A, Goldschmidt H, Ho AD. Quality of life and rehabilitation in social and professional life after autologous stem cell transplantation 7. Ann Oncol 2002;13:209–17.

- Horsboel TA, Nielsen CV, Nielsen B, Jensen C, Andersen NT, De TA. Type of hematological malignancy is crucial for the return to work prognosis: a register-based cohort study 4. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7: 614–23.

- Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, Nahar AM, Mohd Taib NA, Su TT. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review 1. BMC Public Health 2014;14(Suppl 3):S8.

- Smeland KB, Kiserud CE, Lauritzsen GF, Fossa A, Hammerstrom J, Jetne V, et al. High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell support for lymphoma–from experimental to standard treatment 2. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen 2013;133:1735–9.

- Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1993;37:147–53.

- Loge JH, Ekeberg O, Kaasa S. Fatigue in the general Norwegian population: normative data and associations. J Psychosom Res 1998;45:53–665.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review 9. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77.

- Loge JH, Kaasa S. Short form 36 (SF-36) health survey: normative data from the general Norwegian population. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:250–8.

- Ware JE., SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3130–9.

- Bergvik S, Sorlie T, Wynn R, Sexton H. Psychometric properties of the Type D scale (DS14) in Norwegian cardiac patients 6. Scand J Psychol 2010;51:334–40.

- Denollet J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom Med 2005;67:89–97.

- Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. Work Ability Index. 2nd revised edition. 2006.

- Horsboel TA, Nielsen CV, Andersen NT, Nielsen B, De TA. Risk of disability pension for patients diagnosed with haematological malignancies: a register-based cohort study 3. Acta Oncol 2014;53: 724–34.

- Abrahamsen AF, Loge JH, Hannisdal E, Holte H, Kvaloy S. Socio-medical situation for long-term survivors of Hodgkin's disease: a survey of 459 patients treated at one institution. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34:1865–70.

- Gudbergsson SB, Fossa SD, Dahl AA. Are there sex differences in the work ability of cancer survivors? Norwegian experiences from the NOCWO study 8. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:323–31.

- Mols F, Thong MS, van de Poll-Franse LV, Roukema JA, Denollet J. Type D (distressed) personality is associated with poor quality of life and mental health among 3080 cancer survivors 14. J Affect Disord 2012;136:26–34.

- Duijts SF, van Egmond MP, Spelten E, van MP, Anema JR, van der Beek AJ. Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: a systematic review 2. Psychooncology 2014;23:481–92.