Abstract

Background One fifth of all deaths among children in Europe are accounted for by cancer. If this is to be reduced there is a need for studies on not only biology and treatment approaches but also on how social factors influence cure rates. We investigated how various socioeconomic characteristics were associated with survival after childhood cancer.

Material and methods In a nationwide cohort of 3797 children diagnosed with cancer [hematological cancer, central nervous system (CNS) tumors, non-CNS solid tumors] before age 20 between 1990 and 2009 we identified parents and siblings and obtained individual level parental socioeconomic variables and vital status through 2012 by linkage to population-based registries. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dying were estimated using multivariate Cox proportional hazard models.

Results For all children with cancer combined, survival was slightly but not statistically significantly better the higher the education of the mother or the father, and with maternal income. Significantly better survival was observed when parents were living together compared to living alone and worse survival when the child had siblings compared to none. Young (<20) or older (≥40) maternal age showed non-significant associations, but based on small numbers. For hematological cancers, no significant associations were observed. For CNS tumors, better survival was seen with parents living together (HR 0.70, CI 0.51–0.97). For non-CNS solid tumors, survival was better with high education of the mother (HR 0.66, CI 0.44–0.99) compared to basic and worse for children with one (HR 1.45, CI 1.11–1.89) or two or more siblings (HR 1.29, CI 0.93–1.79) (p for trend 0.02) compared to none.

Conclusion The impact of socioeconomic characteristics on childhood cancer survival, despite equal access to protocolled and free-of-charge treatment, warrants further and more direct studies of underlying mechanisms in order to target these as a means to improve survival rates.

All industrialized and most developing countries recognize the special needs of children with cancer and offer what each country regards as the best standard of care during all phases of the treatment trajectory. It is estimated that more than 90% of the 15 000 children in whom cancer is diagnosed annually in the European Union will enter standardized treatment programs, which usually include participation in randomized trials of the effect of new treatments. Survival might be affected not only by participation in trials but also by the compliance of the treating physician to both standard and experimental protocols, the adherence of parents and patients to guidelines for treatment and supportive care, and the interactions of these factors.

Today, 22% of all deaths among children aged 1–14 years in Europe are due to cancer [Citation1]. If this high proportion of cancer-related deaths is to be reduced, studies must be conducted not only on tumor biology and novel treatment approaches but also on how socioeconomic and social factors influence cure rates.

A number of studies have shown an association between socioeconomic position and survival after cancer in adults, with better survival of cancer patients with higher education or high income [Citation2–4]. Few studies, however, have addressed the association between socioeconomic factors and survival after childhood cancer in high income countries. Most of the available studies included only children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or hematological cancer in general, with inconsistent results for a range of socioeconomic position indicators; some finding differences in survival [Citation5–8] and others no differences [Citation9–11]. To our knowledge, the only previous study including childhood cancers at all sites was a Norwegian population-based study of 6280 childhood cancer patients with a mean follow-up of 6.7 years reporting reduced mortality rates from cancers that require lengthy treatment [tumors in the central nervous system (CNS), leukemia, neuroblastomas, and bone tumors] among children whose mothers had higher education or who had no siblings [Citation12].

We investigated the association between socioeconomic position and survival after childhood cancer overall and separately by diagnostic group in order to determine the extent to which these factors influence survival in a large, population-based, nationwide study, with individual level information from Danish public administrative registries for all cases.

Material and methods

Study population

We identified 3797 children in whom cancer was diagnosed under the age of 20 years between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2009 in the Danish Cancer Registry, which contains information on all cancers diagnosed since 1943 [Citation13]. We grouped the cancers into 12 diagnostic groups on the basis of the Birch-Marsden classification [Citation14] (also called the International Classification of Childhood Cancer) and defined three main diagnostic groups for our analyses: hematological malignancies (leukemia and lymphomas; International Classification of Childhood Cancer groups 1 and 2), CNS tumors (International Classification of Childhood Cancer group 3), and non-CNS solid tumors (International Classification of Childhood Cancer groups 4–11).

Identification of families and socioeconomic position

Since 1968, all residents of Denmark have been assigned a unique 10-digit personal identification number by the Danish Civil Registration System which allows accurate linkage among registries [Citation15]. The system also holds information on first-degree relatives, and >99% of parents are identifiable for children born in Denmark after 1970 [Citation16]. Using the children’s personal identification numbers as the key, we identified all parents (n = 7570) and all full siblings (n = 3250) and half siblings (n = 953) who were under the age of 19 in the year of diagnosis of the cancer. Full siblings have the same mother and father, and half siblings have the same mother or father.

We defined socioeconomic position broadly, using individual parents’ educational level as a measure of knowledge-related assets, income as a measure of material resources, parents’ cohabitation status, i.e. living together or alone, as a measure of family social support, and number of siblings as a measure of family obligations, thus covering both socioeconomic position and the broader social factors that affect resources in a family [Citation17]. We include all variables in the study, in order to be able to determine the joint effect of these aspects of socioeconomic position on survival after childhood cancer. We obtained information on parents’ socioeconomic factors for the year before diagnosis of the child from registries on education and income kept by Statistics Denmark [Citation18–20]. Highest attained level of education was categorized into basic education (7–12 years of basic or high school), vocational education (10–12 years), and higher education (≥13 years). Individual disposable income after taxation and interest was categorized into quartiles. As the father’s income was missing for 9% of cases, the mother’s income was used as the measure of material resources. Parents’ cohabitation status was defined as living with a partner (married or cohabiting) or living without a partner (single, widowed, or divorced). Cohabiting, in the absence of marriage was defined as two people of the opposite sex, over the age of 16 years, with a maximum 15 years of age difference, living at the same address with no other adult in residence.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival was our primary outcome. Children were followed up from the date of cancer diagnosis until the date of death from any cause, emigration, or end of follow-up (31 December 2012), whichever occurred first.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI); time since diagnosis was the underlying time scale. After assessment of linearity, the variable ‘child’s age at diagnosis’ was included as a continuous variable. We used the statistical software R, version 3.0.2. [Citation21]. For the survival analyses we used a stepwise model, in which we firstly introduce adjustment for well established prognostic factors as confounders (child’s age at diagnosis, sex, period of diagnosis, and cancer site) and in a further step for factors that may mediate the association between each socioeconomic position (mutual adjustment for other socioeconomic indicators and mother’s age at birth and number of siblings). Hence, the association between each socioeconomic indicator and all-cause mortality were calculated firstly with no adjustment (crude, model 1); in model 2 adjusted for confounders; and in model 3 for socioeconomic and family mediating factors to determine whether these factors mediate the association between socioeconomic factors and survival. Checks for interaction between, respectively, child’s age at diagnosis or number of siblings and mother’s age at child’s birth revealed no interactions. An overall p-value for analysis of variance was reported. Adjusted survival curves were estimated by predicting survival probabilities from the final Cox models.

In order to see if socioeconomic position was differently associated with survival between different diagnostic groups we conducted a number of separate analyses by diagnostic groups although results of such analyses must be taken as an indicator of patterns and less emphasis can be put on the statistical significance level due to a low number of events. We re-ran model 1 and model 3 for the three main diagnostic groups (hematological, CNS, and non-CNS solid tumors) and a separate analysis for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in order to compare our results with those of other studies. We conducted separate analyses for non-CNS solid tumors with a favorable prognosis and standardized therapy, including early surgery (Wilms tumor), and for non-CNS solid tumors that frequently require more complex treatment (bone tumors, liver tumors, neuroblastomas, and rhabdomyosarcomas). We repeated all analyses including half siblings. Finally, we calculated death rates in order to estimate absolute excess risk, with corresponding 95% CIs.

Results

Cancer was diagnosed in 29% of the 3797 children when they were aged 0–4 years and in 33% when they were 15–19 years. The commonest cancers were CNS tumors, followed by leukemia (). Almost half the parents had vocational education, and 80% were living together. About 60% of the childhood cancer patients had one or more full siblings.

Table 1. Characteristics of Danish children with cancer diagnosed in 1990–2009, for all childhood cancers combined and for three main diagnostic groups of cancer.

Survival after childhood cancer

The median follow-up time was 9.0 years (range 0–22 years). There were 841 deaths during follow-up, for an overall survival of 78%.

In the crude analyses, having both parents with higher education, a mother with higher income, higher maternal age, and parents living together were associated with better survival, as was having no siblings, although most estimates did not reach statistical significance (). In general adjustment for confounding and mediating factors resulted in results closer to the null, except for parents living alone [fully adjusted HR, 0.82; 95% CI 0.69–0.99] and having two or more full siblings (fully adjusted HR, 1.26; 95% CI 1.03–1.53).

Table 2. Associations between parental socioeconomic position and survival from childhood cancer.

The worse survival of children with the youngest mothers appeared to be mediated partly through parents’ education, mother’s income, parental cohabitation status, and number of full siblings, the HR decreasing from 1.33 to 1.20, whereas adjustment did not change the better survival of children with the oldest mothers. Addition of half siblings (both all and by the mother only) to the number of full siblings did not change the estimates (data not shown).

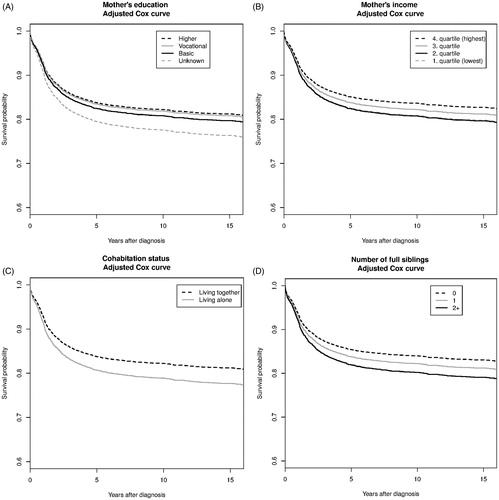

The plots of adjusted survival probabilities by mother’s education, mother’s income, parents’ cohabitation status and number of siblings illustrate that at five years after diagnosis, the absolute adjusted survival ranged from 80% among children whose mother has unknown education to 84% for children whose mother has higher or vocational education (); from 82% to 85% from lowest to highest income of mothers (); from 81% for children with parents living alone to 84% for children with parents living together () and from 82% for children with two or more siblings to 86% for children with no siblings ().

Figure 1. Adjusted Cox curves illustrating the probability of survival over time since diagnosis, stratified by mother’s education (A), mother’s income (B), parents living together or living alone (C), and number of full siblings (D). Adjusted for child’s age at diagnosis, decade of diagnosis, sex, site of cancer, mother’s age at child’s birth, mother’s education, father’s education, mother’s income, parents living together or alone, and number of full siblings.

Survival by diagnostic group

In general, the pattern of a reduced unadjusted HRs for death with higher education, income, parents living together and fewer siblings could be seen in all three diagnostic groups, except for mothers’ education and number of siblings for children with CNS tumors (). After adjustment, children with non-CNS solid tumors who had higher educated mothers survived significantly longer (fully adjusted HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.44–0.99; ), whereas the statistically non-significant, unadjusted better survival of children with hematological cancers whose mothers had higher education was not observed in the fully adjusted model ().

Table 3. Impact of socioeconomic position on overall survival of children with hematological (3A), CNS tumors (3B), and non-CNS solid tumors (3C). Table 3A. Hematological malignancies.

Table 3B. CNS tumors.

Table 3C. Non-CNS solid tumors.

Parents living together was associated with better survival of children with CNS tumors and non-significantly so for children with non-CNS solid tumors, whereas the number of full siblings was most strongly and statistically significantly associated with the survival of children with non-CNS solid tumors, who had a 45% increase in the risk for dying if they had one sibling (95% CI 1.11–1.89) and a 29% increase if they had two or more full siblings (95% CI 0.93–1.79).

In separate analyses for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the risk estimates were closer to null than those for all cancers. Similarly, in separate analyses of subgroups of non-CNS solid tumors that require early surgery or more complex treatment, no difference was found from the results for the combined group of non-CNS solid tumors (data not shown).

Absolute excess risk

Five years after diagnosis, the absolute excess risk for death of the full group of childhood cancer patients was six per 1000 person-years for children of parents living alone when compared with children of parents living together, six per 1000 person-years for children with one full sibling and eight per 1000 person-years for children with two or more full siblings when compared with children with no full siblings ().

Table 4. Absolute excess risk for death after 5 years in children with any pediatric cancer, by parental cohabitation status and number of full siblings.

Discussion

In this population-based nationwide study with complete follow-up, we found that higher socioeconomic position of the parents was associated with better survival of children with cancer. The effects of the different indicators of socioeconomic position differed, however, by cancer site. The beneficial effect of having a mother with higher education and being an only child seemed to be present mainly for children with non-CNS solid tumors and parents living together mainly for children with CNS tumors.

One explanation of our findings might be delayed diagnosis for some social groups [Citation22], whereby a more advanced stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis would result in poorer survival. Another explanation might be a greater communication barrier between socioeconomically disadvantaged families and the health sector. Families depend on information and guidance from health personnel, but general health literacy, communication, and cognitive skills may differ by level of education, resulting in different understanding by parents who receive the same information. Our findings indicate that the problem might be exacerbated for children with cancers that require multidisciplinary treatment, like non-CNS solid tumors [Citation17,Citation23–25], whereas the effect of parents’ socioeconomic position on survival after hematological cancers seems limited.

The fact that parents living together is associated with survival implies that living with a partner might facilitate sharing of the prolonged attention and practical work required in caring for a child with cancer and also for coping with the associated mental challenges and anxiety. Furthermore, living together might enable one parent to reduce his or her working hours to be at the hospital. The finding that having siblings is associated with shorter survival might reflect similar mechanisms: siblings also require time and attention from parents, which could result in less attention to the sick child [Citation26].

Comparison with other studies

Although the impact of socioeconomic position on the chances of survival among children with cancer has drawn attention, the studies published so far have been limited by patient selection (only certain cancer types) or sample size, with limited power and differences in the definition and use of socioeconomic variables across studies. Moreover, dissimilarities in welfare systems, including access to health care and public family support, coverage and distance to treatment facilities, lifestyle and socio-cultural aspects, treatment protocols as well as methodological differences between studies make an international comparison challenging.

We performed this population-based study with complete follow-up of 3797 children with cancer during a diagnostic period from 1990 to 2009, i.e. when contemporary cancer therapies were used. Some previous studies included only children with leukemia [Citation5–8,Citation10], acute lymphoblastic leukemia only [Citation9] or lymphomas [Citation11]. In our subanalyses for all hematological cancers and for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, we found no effect of socioeconomic position on survival. These results are in line with those of a large study in the US (subset of children 0–14 years; n = 4158) [Citation10], a smaller acute lymphoblastic leukemia study in Germany (n = 788) [Citation9], as well as a Canadian study of lymphomas (n = 692) [Citation11]. In contrast, four smaller European studies (n = 714–1559) found associations between various proxies of parental socioeconomic position and survival after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia [Citation5–8]. The associations between better survival and higher maternal education and being an only child were seen mainly for children with non-CNS solid tumors, whereas the association between having parents who live together and survival was attributable mainly to a protective effect in children with CNS tumors and less so in children with non-CNS solid tumors. These findings are partly in line with those of a Norwegian study of 6280 children with cancer of all types diagnosed between 1974 and 2007, in which the mother’s educational level and the number of siblings were associated with survival after cancers with long-term treatment (CNS tumors, leukemia, neuroblastomas, and bone tumors) [Citation12]. They did not find an association between parental marital status and survival, although their definition did not include unmarried parents living together, which in our study constituted some 19%.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strengths of this study include the population-based approach, almost complete inclusion of the study population, and virtually no loss to follow-up. Through the Danish Cancer Registry, we included all children with cancer diagnosed in the period 1990–2009 and investigated the impact of a range of socioeconomic position indicators on survival from various groups of cancer. We were able to obtain individual information on socioeconomic position for both married and non-married parents living together, thus taking into account the joint influence of family and social factors, acknowledging that these factors operate together. We included only cases diagnosed and treated after 1990, when systematic treatment protocols were introduced in Denmark, thus minimizing any differences in cancer outcomes due to socioeconomic position.

A limitation of the study is the size of the cohort, which, however, was unavoidable, in view of the population of the country. The CIs reflect this small study population, so that several estimates failed to reach statistical significance despite clear patterns of risk by social factors. Disposable household income per person would have been a better proxy than separate information on income for mothers and fathers, but this information was not available for parents not living together, where we did not have access to the number of persons living in their respective households.

Siblings born later than the year of diagnosis are not included in the analyses. This is a limitation due to our hypothesis that siblings require attention from the parents, and maybe especially the very young siblings will be extra challenging for the parents while having a child with cancer. Similarly, some of the socioeconomic variables like education and cohabitation may also change during follow-up. However, the status at time of diagnosis reflects the social circumstances at diagnosis and through treatment. Further, due to the nature of the data with no information on the diagnostic process or adherence to treatment protocol we were not able to analyze any underlying causes to the socioeconomic differences in survival that we describe.

Conclusions and policy implications

The potentially preventable fractions of lives depend on socioeconomic position factors that are not – and should not be – modifiable, such as the number of siblings. However, the results of our study suggest that it should be an achievable goal to optimize the survival of the worse-off subpopulations among the childhood cancer cases to the level of those patients who are best-off in terms of survival. The absolute number of deaths potentially attributable to these factors is not trivial. Further investigations should be conducted into when and how disparities are introduced in the trajectory of treatment and recovery of these children.

In conclusion, despite highly specialized, centralized treatment and free access for all children to all health services, not all patients benefit equally from improvements in survival. Our results indicate that parents with short education, who live alone, and who have more than one child might need extra support during the treatment and recovery of their child. Further studies are warranted to investigate possible social differences in parent and patient adherence to treatment and follow-up and investigate any differences in the interactions with physicians.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Danish Cancer Society [grant number R81-A5131-13-S7]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. SBS, KS, SOD conceived and designed the study. SBS, LWL, KKA, JFW and SOD contributed to the collection and assembly of data. SBS, LWL, FE, KKA, JS, JFW, CJ, KS, SOD participated in analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript, and all approved the final version.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Wolfe I, Thompson M, Gill P, Tamburlini G, Blair M, van den Bruel A, et al. Health services for children in western Europe. Lancet 2013;381:1224–34.

- Rachet B, Woods LM, Mitry E, Riga M, Cooper N, Quinn MJ, et al. Cancer survival in England and Wales at the end of the 20th century. Brit J Cancer 2008;99:S2–10.

- Dalton SO, Schuz J, Engholm G, Johansen C, Kjaer SK, Steding-Jessen M, et al. Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003: Summary of findings.. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:2074–85.

- Quaglia A, Lillini R, Mamo C, Ivaldi E, Vercelli M, Group SW. Socio-economic inequalities: A review of methodological issues and the relationships with cancer survival. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013;85:266–77.

- Coebergh JW, van der Does-van den B, Hop WC, van Weerden F, Rammeloo JA, van Steensel HA, et al. Small influence of parental educational level on the survival of children with leukaemia in The Netherlands between 1973 and 1979. Eur J Cancer 1996;32A:286–9.

- Lightfoot TJ, Johnston WT, Simpson J, Smith AG, Ansell P, Crouch S, et al. Survival from childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: The impact of social inequality in the United Kingdom. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:263–9.

- Njoku K, Basta N, Mann KD, McNally RJ, Pearce MS. Socioeconomic variation in survival from childhood leukaemia in northern England, 1968-2010.. Br J Cancer 2013;108:2339–45.

- Sergentanis T, Dessypris N, Kanavidis P, Skalkidis I, Baka M, Polychronopoulou S, et al. Socioeconomic status, area remoteness, and survival from childhood leukemia: Results from the nationwide registry for childhood hematological malignancies in Greece. Eur J Cancer Prev 2013;22:473–9.

- Erdmann F, Kaatsch P, Zeeb H, Roman E, Lightfoot T, Schuz J. Survival from childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in West Germany: Does socio-demographic background matter? Eur J Cancer 2014;50:1345–53.

- Kent EE, Sender LS, Largent JA, Anton-Culver H. Leukemia survival in children, adolescents, and young adults: Influence of socioeconomic status and other demographic factors. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:1409–20.

- Darmawikarta D, Pole JD, Gupta S, Nathan PC, Greenberg M. The association between socioeconomic status and survival among children with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in a universal health care system. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1171–7.

- Syse A, Lyngstad TH, Kravdal O. Is mortality after childhood cancer dependent on social or economic resources of parents? A population-based study. Int J Cancer 2012;130:1870–8.

- Gjerstorff ML. The Danish cancer registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:42–5.

- Birch JM, Marsden HB. A classification scheme for childhood cancer. Int J Cancer 1987;40:620–4.

- Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Bronnum-Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:12–16.

- Pedersen CB, Gotzsche H, Moller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish civil registration system. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull 2006;53:441–9.

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey SG. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:7–12.

- Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:103–5.

- Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:91–4.

- Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:22–5.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014 (http://www.R-project.org/).

- Ahrensberg JM, Schroder H, Hansen RP, Olesen F, Vedsted P. The initial cancer pathway for children - one-fourth wait more than 3 months.. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:655–62.

- Frederiksen BL, Brown PN, Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Osler M. Socioeconomic inequalities in prognostic markers of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Analysis of a national clinical database. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:910–17.

- Dalton SO, Frederiksen BL, Jacobsen E, Steding-Jessen M, Osterlind K, Schuz J, et al. Socioeconomic position, stage of lung cancer and time between referral and diagnosis in Denmark,2001-2008. Br J Cancer 2011;105:1042–8.

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey SG. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:95–101.

- Patterson JM, Holm KE, Gurney JG. The impact of childhood cancer on the family: A qualitative analysis of strains, resources, and coping behaviors. Psychooncology 2004;13:390–407.