Abstract

Two cases of necrotizing soft tissue infection of the lower extremity were treated concurrently but independently. Multimodal therapy including hip joint disarticulation and hyperbaric oxygen therapy was administered, resulting in opposite outcomes: survival and death. Analysis of the relationships between patient outcome and time-course changes in serum diacron-reactive oxygen metabolites (d-ROMs; an index of oxidative stress), antioxidative potential, and cytokines revealed that serum d-ROMs levels decreased with time, but high serum levels of interleukin-10 (anti-inflammatory cytokine) persisted in the patient who died. These findings may reflect an immunosuppressive status unfavorable to infection prevention. Serum d-ROMs may be a prognostic predictor in necrotizing soft tissue infections.

Introduction

Reactive oxygen and free radicals play an important role in host defenses. In recent years, however, oxidative stress that generates excessive amounts of these agents has been reported to be related to various diseases, implying that the stress is the cause of organ/tissue injuries under invasive conditions (Citation1–6) in spite of excessive generation of antioxidants to counteract the oxidative stress (Citation7,8).

Necrotizing fasciitis and gas gangrene are soft tissue infections that progress rapidly and become easily fatal. In recent years, both infections have been frequently regarded as necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs) that must be diagnosed early and be treated effectively because of high mortality rates (Citation9,10). NSTIs can have either an indolent or fulminant presentation, and their clinical course is unpredictable (Citation11). We describe the course of two patients with NSTI of the lower extremity treated concurrently in our institution. In both patients, multimodal therapy including hip joint disarticulation and hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) was administered, but their results were in opposite outcomes: one survived and the other died. We discuss the relationship of changes in serum oxidative and antioxidant (diacron-reactive oxygen metabolites (d-ROMs) and biological antioxidant potential (BAP)) status as well as serum cytokine (interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10) levels which has never been reported concerning outcome.

Case reports

Case 1 (survival case) 54-year-old, male

Clinical diagnosis: Gas gangrene in the right lower extremity.

Chief complaint: Pain in the right lower limb.

Past history: Diabetes mellitus (untreated).

Present illness: Redness, swelling, and pain in the right lower limb, which appeared suddenly without knowledge of special reason, had been conservatively treated under a diagnosis of cellulitis in a private clinic. Because of the ineffectiveness of conservative therapy and onset of consciousness disturbance, he was referred to our institution on day 9 of the disease.

Findings on admission: The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, 6 (E1V1M4); body temperature, 38.5°C; respiratory rate, 35/minute; pulse, 120/minute; and blood pressure, 140/80 mmHg. Necrosis of the right foot was associated with redness (extending to the lower abdominal region), swelling, and heat sensation in the entire lower limb.

Laboratory data on admission: White blood cell count, 12,700/L; hemoglobin, 11.0 g/dL; platelet count, 16,000/L; serum C-reactive protein (CRP), 246 mg/L; and lactate, 3.6 mmol/L.

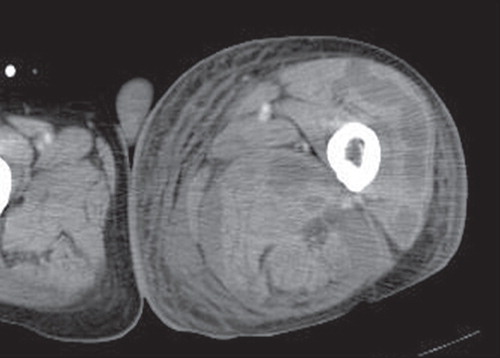

Imaging findings: On CT, a circumferential gas pattern was observed in the right lower limb ().

Figure 1. Computed tomography of the right thigh of case 1. A circumferential gas pattern was observed.

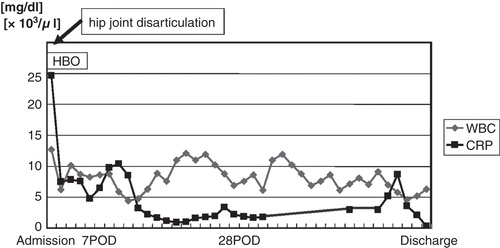

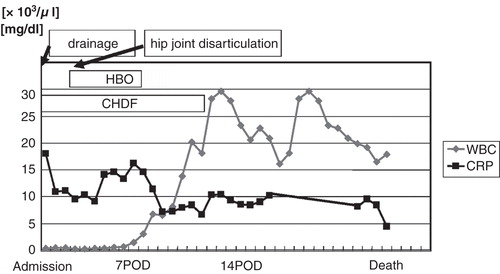

Clinical course after admission: On the day of admission, an immediate disarticulation of the right hip joint was conducted leaving an open wound, necrotic tissue in which was debrided thereafter every day. Peptostreptococcus magnus and Prevotella disiens were identified on wound cultures. Multimodal therapy including HBO therapy and antibiotic therapy were initiated. In 1 month of hospitalization, infection had been controlled, and vacuum-assisted closure therapy was conducted. After 2 months of hospitalization, the patient was transferred to another hospital for prosthetic needs and rehabilitation (). In the second year of follow-up, he was able to walk with a crutch.

Case 2 (death case) 77-year-old, male

Clinical diagnosis: Necrotizing fasciitis of the left lower extremity.

Chief complaint: Pain in the left lower limb.

Past history: Non-contributory.

Present illness: He fell down in the house and had pain in his left thigh. Five days later, redness and swelling appeared in the entire left lower limb and gradually worsened in association with breathing difficulty and consciousness disturbance. Two weeks after the onset of this disease, he visited our hospital.

Findings on admission: The GCS score, 10 (E3V3M4); body temperature, 36.3°C; respiratory rate, 30/minute; pulse, 137/minute; blood pressure, 125/58 mmHg. In the left thigh, swelling, heat sensation, and redness were observed, and the limb was edematous.

Laboratory data on admission: White blood cell count, 400/L; hemoglobin, 10.4 g/dL; platelet count, 102,000/L; CRP, 180 mg/L; lactate, 6.8 mmol/L.

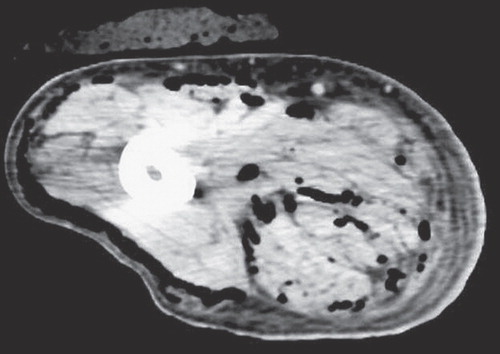

Imaging findings: On CT, there was a circumferential abscess pattern ().

Figure 3. Computed tomography of the left thigh of case 2. A circumferential abscess pattern was observed.

Clinical course after admission: On the day of hospitalization, incisions for drainage were made through the lateral and medial sides of the left thigh. Streptococcus pneumoniae was detected on wound cultures. Postoperatively, necrosis proceeded in the distal direction to the left lower limb. Therefore, 4 days after admission, amputation of the left femur was conducted and followed by hip joint disarticulation in consideration of any possibility of remnants of infected tissue at the amputated stump. The necrosis of the stump was debrided every day and treated as an open wound. Intensive multidisciplinary therapy including HBO and antibiotic therapy was commenced, but intractable disseminated intravascular coagulation developed. The patient died 1 month after admission ().

Time-course changes in serum d-ROMs, BAP, and cytokines (IL-6, IL-10)

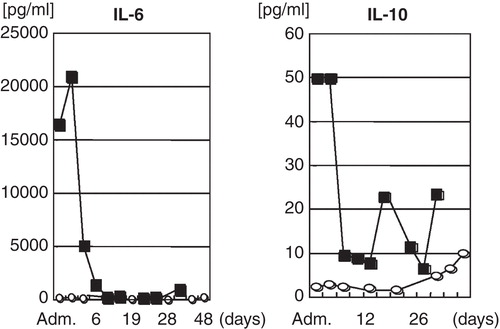

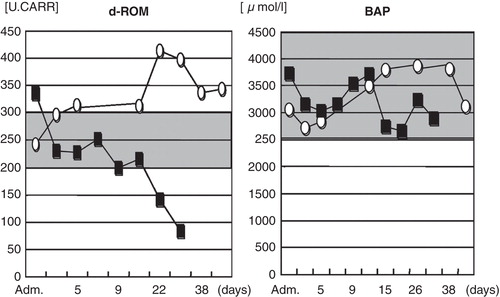

Serum d-ROMs and BAP were measured by an automated analyzer (FRAS4; H&D srl, Parma) for determining oxidant and antioxidant status. Serum d-ROM levels increased in the patient who survived (case 1) but decreased gradually in the patient who died (case 2). Serum BAP levels remained within the normal range throughout the course in both cases (). Levels of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were high in the early phase of the hospitalization of the patient who died ().

Figure 5. Changes in serum d-ROMs and BAP. Serum d-ROM levels were increased in the patient who survived (case 1, open symbols) but decreased with time in the patient who died (case 2, closed symbols). Serum BAP levels remained within the normal range throughout the course of the disease in both cases. (Adm. = admission). Grey area = normal range

Discussion

Reactive oxygen and free radicals play a critical role in host defense processes; however, if excessively produced, they become oxidative stressors and contribute to ischemia-reperfusion injury and various diseases (Citation1–6). It has been reported that levels of reactive oxygen species and free radicals with short lifetimes and high reactivity are difficult to measure in the patients (Citation12). The FRAS4 method for the assessment of d-ROMs, used in the present study, indirectly measures reactive oxygen and free radicals in vivo by determining the blood concentrations of hydroperoxides (generated by interactions with these mediators) via color reactions. BAP measured by the FRAS4 method reflects the ability of blood antioxidants to stop oxidation by providing electrons for the reduction of reactive oxygen species and free radicals. Activation of neutrophils and other inflammatory cells in severe infections, injury due to shock-associated ischemia reperfusion, and so forth are thought to increase the production of reactive oxygen species and free radicals (Citation13). Therefore, in cases of severe infection and severe injury, increased d-ROMs and decreased BAP would be anticipated. Nevertheless, in the patient who died, d-ROMs decreased gradually until death. This finding is consistent with the findings of a study that surveyed patients with severe burns in our institution (Citation14).

In human beings there is a balance between host defenses and auto-destruction by production of appropriate amounts of various cytokines and other mediators in response to invasive stimuli. Under severe infectious conditions, however, inflammatory cytokines are relatively predominant, leading to a state of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (Citation15), and, as a result, levels of reactive oxygen and free radicals increase. Persistent SIRS triggers the onset of multiple organ failure or dysfunction. Conversely, the host seeks to produce the anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and intrinsic inflammatory-cytokine antagonists for the control of SIRS. If these anti-inflammatory mediators become relatively predominant, the host would suffer from impairment of immunocompetent cells and fall into compensated anti-inflammatory response syndrome (CARS) (Citation16), in which the host defense against infection is depressed.

In this study, the patient who died had high levels of both inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 on admission and a persistent, relatively high level of IL-10 resulting in decreasing levels of d-ROMs throughout the clinical course of illness. These findings indicate that the cytokine balance in the patient who died had shifted toward an anti-inflammation predominance, inducing the state of CARS. Serum d-ROMs may be a robust prognostic predictor in necrotizing soft tissue infections.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Dohi K, Ohtaki H, Inn R, Ikeda Y, Shioda HS, Aruga T. Peroxynitrite and caspase-3 expression after ischemia/reperfusion in mouse cardiac arrest model. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2003;86:87–91.

- Ihara Y, Toyokuni S, Uchida K, Odaka H, Tanaka T, Ikeda H, Hyperglycemia causes oxidative stress in pancreatic beta-cells of GK rats, a model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48:927–32.

- Loft S, Poulsen HE. Cancer risk and oxidative DNA damage in man. J Mol Med. 1996;74:297–312.

- Chan PH. Role of oxidants in ischemic brain damage. Stroke. 1996;27:1124–9.

- Lewen A, Matz P, Chan PH. Free radical pathways in CNS injury. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:871–90.

- Lim HB, Ichinose T, Miyabara Y, Takano H, Kumagai Y, Shimojyo N, Involvement of superoxide and nitric oxide on airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness induced by diesel exhaust particles in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:635–44.

- Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science. 1987;235:1043–6.

- Dohi K, Satoh K, Ohtaki H, Shioda S, Miyake Y, Shindo M, Elevated plasma levels of bilirubin in patients with neurotrauma reflect its pathophysiological role in free radical scavenging. In Vivo. 2005;19:855–60.

- McHenry CR, Piotrowski JJ, Petrinic D, Malangoni MA. Determinants of mortality for necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Ann Surg. 1995;221:558–65.

- Elliot DC, Kufera JA, Myers RAM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:672–83.

- Wilson B. Nectotizing fasciitis. Am Surg. 1952;18:416–31.

- Toyokuni S, Tanaka T, Hattori Y, Nishiyama Y, Yoshida A, Uchida K, Quantitative immunohistochemical determination of 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine by a monoclonal antibody N45.1: its application to ferric nitrilotriacetate-induced renal carcinogenesis model. Lab Invest. 1997;76:365–74.

- Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL. Sepsis syndromes: understanding the role of innate and acquired immunity. Shock. 2001;16:83–96.

- Shinozawa Y, Kobayashi M. [Substrate metabolism and nutritional support in patients with critically ill and/or severe sepsis]. Jap J Surg Metab Nutr. 2008;42:45–59; In Japanese.

- American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74.

- Bone RC. Sir Isaac Newton, sepsis, SIRS and CARS. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1125–8.