Abstract

Clinical know-how and skills as well as up-to-date scientific evidence are cornerstones for providing effective treatment for patients. However, in order to improve the effectiveness of treatment in ordinary practice, also appropriate documentation of care at the health care units and benchmarking based on this documentation are needed. This article presents the new concept of real-effectiveness medicine (REM) which pursues the best effectiveness of patient care in the real-world setting. In order to reach the goal, four layers of information are utilized: 1) good medical know-how and skills combined with the patient view, 2) up-to-date scientific evidence, 3) continuous documentation of performance in ordinary settings, and 4) benchmarking between providers. The new framework is suggested for clinicians, organizations, policy-makers, and researchers.

Key messages

Good clinical know-how and skills as well as up-to-date scientific evidence, especially from randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews, are the cornerstones of effective patient care.

Scientifically sound assessment of health care unit performance and benchmarking with peer units produces essential data for improving quality of treatment processes and effectiveness of the clinical pathway. The validity of the observational real-life data is essential, and there is an obvious need for more investment in health service research.

The advancement of real-world effectiveness by clinicians, organizations, and policy-makers should be based on continuous development of good medical know-how and skills, use of up-to-date scientific evidence, continuous documentation of performance, and benchmarking between providers.

Introduction

All activities within clinical medicine (education, clinical work, research) have an ultimate aim to advance the health and well-being of patients. Combining clinical know-how and up-to-date scientific evidence, this goal can be approached. However, in addition there is a need for valid data on actual performance at the ordinary praxis. This information should preferably be disease-specific: what is the clinical profile of patients having a particular disease, how the patients are treated, and what are the outcomes of the treatment at one’s own health care unit. By comparing these data with peers, one can assess the appropriateness of the treatment processes and, if baseline confounding can be controlled, even estimate differences in treatment outcomes. Benchmarking data can be used to improve the quality of patient care.

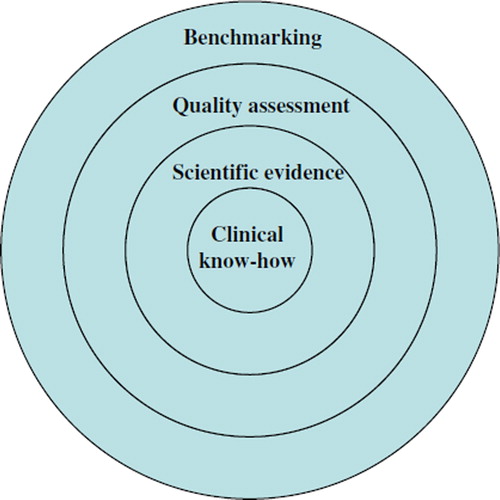

This article presents the new concept of real-effectiveness medicine (REM), which can be defined as a systematic undertaking to utilize simultaneously information and activities on four specific layers for the pursuit of best effectiveness of patient care in the real (ordinary) world setting. The four layers include good medical know-how and skills combined with patients’ views, up-to-date scientific evidence, continuous documentation of performance in ordinary settings, and benchmarking between providers.

The aim of this paper is to consider the need for the new concept, describe what real-effectiveness medicine is, and make recommendations on how to practice and promote this concept for the pursuit of effective and high-value (cost-effective) health care for each patient and for society.

Why the new paradigm of real-effectiveness medicine?

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) provides the least biased information on the efficacy of medical interventions and creates the basis for systematic reviews on efficacy of interventions. However, RCTs face problems due to the often narrow eligibility criteria for the patients and the better than average know-how in the units providing the interventions. Thus the efficacy shown by trials and systematic reviews is often better than the effectiveness provided by average health care units for average patients, and the extrapolation of the results to ordinary settings is often uncertain (Citation1).

RCTs are based on a strict PICO-type (patient, intervention, comparator, outcome) research question and do not consider how effective the whole clinical pathway is. For example, a drug-eluting stent may be compared with a bare metal stent for acute myocardial infarction, while this procedure represents only one part of the treatment process in the hospital taking care of the acute phase, and, most importantly, only a tiny part of the whole clinical pathway consisting of follow-up, treatment, and rehabilitation in the hospital and further in the primary care. Thus, in the real world the effectiveness is determined not solely by a single intervention but by how well the whole clinical pathway works. Furthermore, in some cases randomized trials cannot be used for ethical reasons—for example in assessing the effectiveness of treatments for the very-low-birth-weight infants who would die without active treatment. For these cases observational studies represent the only feasible option to provide data on effectiveness (Citation2).

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been most influential in advancing systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials as a tool for synthesizing comprehensively and with as little bias as possible the current evidence of relevant clinical questions. EBM has also promoted clinical work based on explicit and judicious assessment of the underlying evidence (Citation3). However, there is evidence that many patients do not receive the appropriate care (Citation4).

Due to the limited resources in health care one must also question the effectiveness in relation to the invested resources—i.e. cost-effectiveness. The problems with translating cost-effectiveness data from a randomized trial to another setting, especially to another country, are paramount, and so far there have been only attempts to assess in which cases this translation is justifiable (Citation5,Citation6).

For these reasons there is a need to obtain data also on real-life praxis and utilize this information for better effectiveness in ordinary settings.

What is real-effectiveness medicine?

The first layer of real-effectiveness medicine includes use of good medical know-how and skills, which provide means for logical clinical decision-making (). In order to select effective treatments one has to consider both diagnostic and other patient characteristics, including co-morbid conditions, before deciding upon the best treatment option. This is rather similar to the PICO concept (patient, intervention, comparator, outcome) recommended for clinical trials and systematic reviews for specifying the study question (Citation7). It is noteworthy that often the recommendations in clinical guidelines are based on the current views of the most experienced and knowledgeable clinicians, because reliable scientific evidence is not available (Citation1).

Figure 1. The four layers of information of the real-effectiveness medicine in pursuit of the best possible effectiveness of patient care in the real-world setting. In the decision-making process real-effectiveness medicine uses clinical know-how and patients’ views (layer one), current best scientific evidence (layer two), documented data of own unit's or clinical pathways’ performance including efforts for quality improvement (layer three), and benchmarking of own data with units or clinical pathways of peers (layer four). At all four layers one needs to consider patient characteristics, diagnostic criteria, treatment alternatives, and outcomes for each patient. The information from these four layers is used for continuous improvement of the treatment practices at one's own unit and through the whole clinical pathway.

The second layer which should be taken into consideration when making clinical decisions includes utilization of the up-to-date scientific evidence, particularly from RCTs and systematic reviews as well as information supported by these like health technology assessment (HTA) reports and clinical guidelines. Also other scientific and patient-based information (such as scientific data on diagnostic tests and patients’ values and preferences) according to the concept of evidence-based medicine should be considered.

The third layer includes standardized documentation of the performance of health care units and continuous quality improvement measures based on the performance data. Optimally the performance of the whole clinical pathway encompassing primary, secondary, and tertiary care will be assessed. The focus should be on implementing high-value care based on the principles of evidence-based medicine. The effective ways to promote the uptake of research findings into routine health care suggested by implementation science should be utilized (Citation8). Obtaining a quality certification based on fulfillment of established criteria increases the transparency of the treatment processes. The focus of the performance indicators should be on those for which there is scientific evidence that a particular change in the care process leads to improved outcomes, the indicators are such that they capture whether the process is indeed provided, the process indicator lies sufficiently near the important outcomes, and there is low or no risk of inducing adverse consequences (Citation9). In some cases also incidence and outcome measures can be used for performance assessment. In a large community-based population of more than 3 million persons, the incidence as well as 1-month mortality for acute myocardial infarction was found to decrease during a 9-year time period (Citation10). A similar trend was found in a comprehensive nation-wide database showing only very modest increases in cost while the up to 1-year mortality for myocardial infarction decreased substantially (Citation11).

The fourth layer includes benchmarking (learning from the best practices of peers) between treatment providers. Simultaneous information of patient characteristics, diagnostic procedures, and treatments, and of the outcomes is needed for the comparisons between providers or for comparisons over time. If baseline imbalances between patients treated by different providers can be satisfactorily adjusted for, comparisons based on treatment outcomes can be made (Citation12). If feasible, all clinically important patient-relevant outcomes should be documented. The term effectiveness in real-effectiveness medicine covers both favorable and adverse (counter-) effects produced by the health care units. The reasons for differences in outcomes can be assessed based on data on baseline patient characteristics and treatment processes, but this often needs to be supported by clinical reasoning of the probable determinants of favorable or unfavorable outcomes.

With continuous benchmarking the effects of changes in treatment processes on patient outcomes should be documented and further quality improvement activities initiated. Thus the recording of relative differences in effectiveness between health care providers is only an intermediate aim for the real-effectiveness medicine. The primary aim is, through continuous improvement of processes (based on the probable reasons for between-provider differences), improvement of the real effectiveness in ordinary patient care.

For valid benchmarking through the clinical pathway, comprehensive register data and the possibility of linking different registers and combining information from different sources are needed. This can be accomplished if there is a unique personal identification number and legislation allows data linkage on an individual level. Unfortunately only in a limited number of countries it is possible to follow the patients through the entire clinical pathway. However, it is always possible to compare the performance of individual health care units treating similar patients by documenting patient characteristics, treatments, costs, and outcomes in a standard way.

A real-effectiveness medicine approach adds to the evidence-based medicine the layers three and four: the documentation of actual performance of a particular health care unit (or a hospital or a hospital district). Furthermore the effectiveness is not limited to single interventions but encompasses all the processes in patient care and preferably the whole clinical pathway allowing in some cases even information on outcome at several time points. Thus the comparison is between two or more health care units or clinical pathways, not solely between specific treatments or preplanned treatment algorithms as in randomized trials.

How to practice real-effectiveness medicine?

Advancement of clinical know-how and exploitation of up-to-date scientific evidence are the cornerstones of effective patient care. As there is plenty of literature available on these issues, the focus in the present paper is on standardized documentation of ordinary praxis and especially on valid benchmarking between health care providers. These activities build upon judicious use of the evidence-based medicine concept in the ordinary practice.

A valid comparison between different health care units requires appropriate eligibility criteria for the patients as well as risk adjustment for confounding factors at baseline. The eligibility criteria in case of myocardial infarction, for example, might be restricted to new episodes (e.g. patients have not been hospitalized for myocardial infarction during the previous year) and to those patients who have not been institutionalized before hospital admission. Risk adjustment for age, gender, co-morbidity, and other confounding factors should be made using information from the treatment units and when available also from registers (Citation12).

The risk of bias of observational studies is usually much higher than that of randomized trials, and up-to-date methodological knowledge and methods should be utilized to judge the validity of observational data for comparative research on intended effects (Citation13). The most unbiased data can be obtained when the allocation of patients to a particular unit is unrelated to the outcome (Citation14). In some cases unbiased analysis can be aided by an instrumental variable, which determines treatment allocation but is not related to outcome. For example, in a study assessing the ability of designated stroke centers to decrease the mortality of stroke patients in comparison with non-designated stroke centers, an instrumental variable based on difference in distance to the two treatment sites was employed (Citation15). Researchers made additional analyses to ensure the validity of the results, particularly a sensitivity analysis on subgroups of stroke patients and a specificity analysis on mortality for two other life-threatening conditions in the hospitals having or not having a designated stroke center.

Once there are comparable data to allow valid comparisons between health service providers of treatment processes, use of resources, outcomes, and costs for a particular disease, the analyses should be extended to evaluate factors that influence the differences at health care unit or regional levels. Methods for statistical analyses have been developed and utilized for these comparisons (Citation12). Auditing of the services in the units may also be needed to get further information of the differences in the treatment processes. For example, in Finland rather large differences in mortality rates of very-low-birth-weight infants were found between university hospitals providing tertiary care and central hospitals providing secondary care (Citation16). The mortality of infants born during the day-time did not differ, but during night-time the central hospitals’ performance was weaker. The main reason for this difference was considered to be the small night-time expert resources for pediatric intensive care in the central hospitals. Based on these findings centralization of very small babies to university hospitals has increased in Finland during the last 5 years.

The benchmarking can be extended to international comparisons, which must again be done within specific indications that have been predefined to create sufficiently homogeneous patient populations. In the recently launched EuroHOPE program, which includes five indications (stroke, acute myocardial infarction, breast cancer, very-low-birth-weight infants, and hip fracture), the benchmarking will occur between seven European countries (http://eurohope.info/).

How to promote real-effectiveness medicine?

Promotion of good clinical know-how and an evidence-based medicine approach create the mainstay of effectiveness in ordinary practice.

Concerning documentation and benchmarking, validation work needs to be carried out in order to ascertain the risk of bias and comparability of register data aimed often at mainly administrative purposes, such as data from the inpatient register and the cause-of-death register (Citation17).

Electronic patient record systems will bring new opportunities for real-effectiveness medicine. However, development of patient record systems is not only a technological matter, but needs carefully planned definitions and classifications. Researchers and clinicians should be involved in the definition of the data. A lot of work needs to be done to establish standardized documenting of health care units’ performance on various disease indications and to improve the quality of existing registers. A special concern is lack of or poor-quality data on primary health care services (Citation18).

It is most important to assess whether treatment suggested by evidence-based guidelines is actually implemented in ordinary practice. In a study utilizing the population-based South London Stroke Register, the appropriateness of treatment had improved considerably from 1995 to 2009, but the implementation of evidence-based care was still not optimal, and there were inequalities between socio-economic groups (Citation19). In a Swedish register study prescription of statin and anticoagulant therapy was associated with reduced risk of death but seemed to be under-used for elderly patients (Citation20).

Conclusions

According to the real-effectiveness medicine concept, promotion of good clinical know-how and skills and the evidence-based medicine approach are mandatory for effective patient care.

However, RCTs and systematic reviews will always be unable to answer the real-world question of what the effectiveness of a particular treatment unit is in comparison with other units treating similar patients. Furthermore, the knowledge of the effectiveness and costs of a single procedure for a particular disease is not enough to evaluate the outcome dependent on the whole clinical pathway. Even for single treatments the generalizability of the findings from RCTs to ordinary settings is often difficult, and there is no method enabling a quantitative extrapolation of the efficacy data to real-world circumstances.

Scientifically sound assessment of health care units’ performance and benchmarking with peer units produces data that support decision-making and is helpful for clinicians, health care directors, and policy-makers. Clinicians are able to compare their own performance by using data on patient characteristics, process indicators, outcomes, and costs. As, in many cases, unbiased comparisons of treatment outcomes are not possible, descriptive data on how well patients have been treated according to current scientific evidence provide most valuable information. For example, as there are data on effectiveness of stroke centers, the primary aim of the hospitals treating stroke patients may be quality improvement and a status of a designated stroke center. Lack of statistical power for assessment of relative differences in effectiveness between treatment providers may also limit possibilities to extend benchmarking to outcome indicators. The validity of the observational real-life data is crucial, and thus health service research should be promoted.

The ultimate aim of real-effectiveness medicine is to produce as much good and as little harm as possible for each patient, with reasonable costs to the society. Real-effectiveness medicine also extends the prioritization of alternatives from one single intervention to the whole clinical pathway. The advancement of real-world effectiveness should be based on combining and continuously developing the four elements: good clinical know-how and skills combined with patients’ views, scientific evidence, continuous documentation of performance in ordinary settings, and benchmarking between providers. The new framework is suggested for clinicians, organizations, policy-makers, and researchers.

Declaration of interest: The author states no conflict of interest and has received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Croft P, Malmivaara A, van Tulder M. The pros and cons of evidence-based medicine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:E1121–5.

- Häkkinen U. The PERFECT project: measuring performance of health care episodes. Ann Med. 2011;43 Suppl 1:S1–3.

- Sackett D. Evidence based medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362: 1225–30.

- Welte R, Feenstra T, Jager H, Leidl R. A decision chart for assessing and improving the transferability of economic evaluation results between countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:857–76.

- Knies S, Ament AJ, Evers SM, Severens JL. The transferability of economic evaluations: testing the model of Welte. Value Health. 2009;12:730–8.

- Malmivaara A, Koes B, Bouter L, van Tulder MW. Applicability and clinical relevance of results in randomized controlled trials. The Cochrane review on exercise therapy for low back pain as an example. Spine. 2006;31:1405–9.

- Rubenstein LV, Pugh J. Strategies for promoting organizational and practice change by advancing implementation research. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S58–64.

- Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, Wachter RM. Accountability measures—using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:683–8.

- Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2155–65.

- Häkkinen U, Hartikainen J, Juntunen M, Malmivaara A, Peltola M, Tierala I. Analysing current trends in care of acute myocardial infarction using PERFECT data. Ann Med. 2011;43 Suppl 1:S14–21.

- Peltola M, Juntunen M, Häkkinen U, Rosenqvist G, Seppälä TT, Sund R. A methodological approach for register-based evaluation of cost and outcomes in health care. Ann Med. 2011;43 Suppl 1:S4–13.

- Norris SL, Atkins D, Bruening W. Observational studies in systemic reviews of comparative effectiveness: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1178–86.

- Vandenbroucke JP. When are observational studies as credible as randomised trials? Lancet. 2004;363:1728–31.

- Xian Y, Holloway RG, Chan PS, Noyes K, Shah MN, Ting HH, . Association between stroke center hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke and mortality. JAMA. 2011;305:373–80.

- Rautava L, Lehtonen L, Peltola M, Korvenranta E, Korvenranta H, Linna M,. PERFECT Preterm Infant Study Group. The effect of birth in secondary- or tertiary-level hospitals in Finland on mortality in very preterm infants: a birth-register study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e257–63.

- Appelros P, Terént A. Validation of the Swedish inpatient and cause-of-death registers in the context of stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;123:289–93.

- Häkkinen U, Malmivaara A, Sund R. PERFECT—conclusions and future developments. Ann Med. 2011;43 Suppl 1:S54–7.

- Addo J, Bhalla A, Crichton S, Rudd AG, McKevitt C, Wolfe CD. Provision of acute stroke care and associated factors in a multiethnic population: prospective study with the South London Stroke Register. BMJ. 2011;342:d744.

- Asberg S, Henriksson KM, Farahmand B, Asplund K, Norrving B, Appelros P, . Ischemic stroke and secondary prevention in clinical practice: a cohort study of 14,529 patients in the Swedish Stroke Register. Stroke. 2010;41:1338–42.