Abstract

Diabetic and new-onset diabetic patients with hypertension have higher cardiac morbidity than patients without diabetes. We aimed to investigate whether baseline predictors of cardiac morbidity, the major constituent of the primary endpoint in the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial, were different in patients with diabetes and new-onset diabetes compared to patients without diabetes. In total, 15,245 high-risk hypertensive patients in the VALUE trial were followed for an average of 4.2 years. At baseline, 5250 patients were diabetic by the 1999 World Health Organization criteria, 1298 patients developed new-onset diabetes and 8697 patients stayed non-diabetic during follow-up. Cardiac morbidity was defined as a composite of myocardial infarction and heart failure requiring hospitalization, and baseline predictors were identified by univariate and multivariate stepwise Cox regression analyses. History of coronary heart disease (CHD) and age were the most important predictors of cardiac morbidity in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. History of CHD, history of stroke and age were the only significant predictors of cardiac morbidity in patients with new-onset diabetes. Predictors of cardiac morbidity, in particular history of CHD and age, were essentially the same in high-risk hypertensive patients with diabetes, new-onset diabetes and without diabetes who participated in the VALUE trial.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is strongly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and established diabetes mellitus is considered to be a coronary artery disease risk equivalent.[Citation1–5] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 350 million people worldwide have diabetes and projects that diabetes deaths will double between 2005 and 2030.[Citation6] Diabetes mellitus doubles the age-adjusted risk of cardiovascular disease in men and triples this risk in women.[Citation7] Although diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events, the Framingham study has shown that much of this excess risk is attributable to coexistent hypertension.[Citation8] Hypertensive patients have an increased risk of developing diabetes and the two conditions frequently cluster together, and synergistically increase the susceptibility to cardiovascular disease.[Citation9]

In the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial, 15,245 high-risk hypertensive patients were followed for an average of 4.2 years [Citation10] and 1298 patients developed new-onset diabetes.[Citation11] The importance of new-onset diabetes mellitus in trials have been questioned, as clinically significant effects of diabetes development on macrovascular and microvascular complications during trial follow-up have not been seen in all trials.[Citation12] We have previously shown that patients with new-onset diabetes in the VALUE trial developed more non-fatal cardiovascular events, especially more congestive heart failure, than patients without diabetes.[Citation13] Since there are multiple cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes,[Citation14,Citation15] and because we are not aware of any previous study of predictors of cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients who develop diabetes during antihypertensive treatment, we aimed to investigate predictors of cardiac morbidity to see whether predictors differed between patients with diabetes, those with new-onset diabetes and those without diabetes who participated in the VALUE trial. We investigated predictors of cardiac morbidity for consistency [Citation13] and because this was the major component of the primary endpoint [Citation10] in the VALUE trial.

Materials and methods

Study design

The VALUE trial was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial designed to compare the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan with the calcium channel blocker amlodipine in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk, based on the hypothesis that for the same level of blood pressure control, a valsartan-based regimen would reduce cardiac morbidity and mortality more than an amlodipine-based regimen.[Citation10] VALUE enrolled 15,245 hypertensive men and women of any ethnic background, aged 50 years or older, with a high risk of cardiac events on the basis of age, gender, and a list of cardiovascular risk factors and disease factors.[Citation10] As many as 5250 patients were diabetic at baseline by the 1999 WHO criteria and among the 9995 non-diabetic patients, 1298 patients developed diabetes during the follow-up.[Citation11] The baseline characteristics of these groups are shown in Table s.1.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint in the VALUE trial was time to first cardiac event, defined as a composite of sudden cardiac death, fatal myocardial infarction, death during or after percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft procedure, death due to heart failure, and death associated with recent myocardial infarction on autopsy, heart failure requiring hospital management, non-fatal myocardial infarction or emergency procedures to prevent myocardial infarction. Prespecified secondary endpoints were fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction, fatal and non-fatal heart failure, and fatal and non-fatal stroke. Analyses of all-cause mortality and new-onset diabetes were also prespecified.[Citation16] The data on fatal events in the new-onset diabetes population could only be counted and occur after the time of the diabetes diagnosis, leaving the follow-up time in the new-onset diabetics to be lower and the event rate “falsely” low compared to the baseline diabetics and non-diabetics who had events counted throughout the trial. We therefore aimed to investigate the predictors of cardiac morbidity, defined as myocardial infarction and heart failure requiring hospitalization in the patients with diabetes at baseline, new-onset diabetes during the trial and never diabetes. The definition of the cardiac morbidity also included emergency thrombolytic/fibrinolytic treatment and/or emergency percutaneous coronary intervention/coronary artery bypass graft to avoid fully blown MI, verified by ST-segment elevation on the electrocardiogram and/or typical enzyme pattern. Subsidiary exploratory analysis of the components of myocardial infarction and heart failure also included fatal events.

Data analysis

Eighteen potential baseline predictors were registered in the database and could be investigated (). The predictors included in the analyses were demographic risk and disease factors, previous cardiovascular diseases and antihypertensive treatment, clinical and biochemical variables at baseline, and randomized study drug (amlodipine/valsartan).

Table 1. Investigated baseline predictors.

We evaluated the 18 potential predictors by the three patient groups; baseline diabetes, new-onset diabetes and never diabetes. Univariate and multivariate stepwise Cox regression analyses were used and potential baseline predictors of cardiac morbidity were identified. Multivariate Cox regression models were then run with all baseline covariables included in the models. The results are presented as chi-squared values and hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the possible differences in predictors between the three groups were evaluated in terms of significance criteria to limit type I errors. An overall type I error of 5% across all covariates was approximately achieved by using alpha = 0.001 (mildly relaxing the likely overly conservative Bonferroni approach of 0.05/62 = 0.000806) to judge whether terms were significant.

Results

The patients with diabetes at baseline and the patients with new-onset diabetes had more cardiovascular events than the patients without diabetes. The event rates in these three groups were 2.68, 1.86 and 1.33 per 100 patient-years, respectively. The increases in the two groups of patients with diabetes were thus 101% (95% CI 78–228) and 40% (95% CI 13–72) above the event rate in the patients with never diabetes, respectively (). This effect was even more pronounced after adjustment for the candidate baseline predictors (data not shown). With the inherent limitation of the false lower mortality in the group of patients with new-onset diabetes, the total event rate of both fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction and fatal and non-fatal heart failure also showed a graded risk reduction from diabetes at baseline to new-onset diabetes to never diabetes ().

Table 2. Cardiac morbidity (non-fatal myocardial infarction and heart failure) and total myocardial infarctions and heart failures in patients with baseline diabetes mellitus, new-onset diabetes and never diabetes.

In the patients with diabetes at baseline, history of coronary heart disease (CHD), age and left ventricular hypertrophy were the three most important predictors in the univariate analysis (Table s.2). In the patients with new-onset diabetes, history of CHD, history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), age and diastolic blood pressure were statistically significant although weak predictors (Table s.3). History of CHD, age and left ventricular hypertrophy were the most significant predictors in the never-diabetic patients (Table s.4).

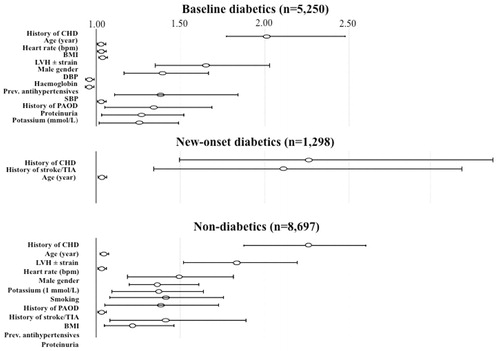

History of CHD and age were among the most important predictors in all three patient groups also in the stepwise forward multivariate analyses (). Heart rate, body mass index, left ventricular hypertrophy and history of stroke or TIA were among the other significant predictors in the multivariate analyses. The statistically significant predictors in the three patient groups are shown in by their hazard ratios and decreasing chi-square value (a hazard ratio above 1 indicates an increased risk of cardiac morbidity). History of CHD and stroke/TIA stand out in the patients with new-onset diabetes; although significant, the wide confidence intervals and weak p values are explained by the modest number of patients in this group (n = 1298), while the impact of age is identical in all three groups of patients.

Figure 1. Graphs showing hazard ratios of predictors of cardiac morbidity in patients with diabetics (upper panel), new-onset diabetics (middle panel) and never diabetes (lower panel) by decreasing chi-square value. Age, heart rate (bpm, beats per minute), body mass index (BMI), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), haemoglobin and systolic blood pressure (SBP) are shown per unit. CHD, coronary heart disease; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; PAOD, peripheral artery occlusive disease; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Table 3. The most important predictors of cardiac morbidity by stepwise multivariate regression analyses ranged by decreasing hazard ratio (HR) and the three diabetes subgroup (baseline diabetes, new-onset diabetes and never diabetes).

The multivariate full Cox regression analyses with all baseline covariables included in the models () confirmed that history of CHD and history of stroke were significant (p < 0.001) baseline predictors of cardiac morbidity in the patients with new-onset diabetes.

Table 4. Significant (p < 0.001) baseline predictors of cardiac morbidity by multivariate full Cox regression analyses (all baseline covariables included in the models) ranged by decreasing hazard ratio (HR) and the three diabetes subgroups (baseline diabetes, new-onset diabetes and never diabetes).

Discussion

We found that the significant predictors of cardiac morbidity in the patients with diabetes in the VALUE trial were almost the same compared as in the patients without diabetes. The patient group with new-onset diabetes was smaller than the other two groups, leaving the result more unreliable; however, the results were consistent and confirmed in the full multivariate model. History of CHD was the most important predictor of cardiac events (new myocardial infarction or heart failure). Diabetes mellitus is known to be a CHD equivalent [Citation2] and the patients with diabetes mellitus at baseline had twice the risk of cardiac morbidity as the patients without diabetes in the VALUE trial.[Citation13]

The risk of cardiac events in our analysis increases with age, as expected. A better and more comprehensive way to investigate the overall burden of risk factors may be to estimate the lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease. In a published meta-analysis, the differences in risk factor burden were translated into marked differences in lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease.[Citation17] The individuals with an optimal risk-factor profile (optimal blood pressure, optimal cholesterol level, non-diabetic, non-smokers) had a lower risk of cardiovascular death (4.7% vs 29.6% in men, 6.4% vs 20.5% in women), myocardial infarction (3.6% vs 37.5% in men, < 1% vs 18.3% in women) and stroke (2.3% vs 8.3% in men, 5.3% vs 10.7% in women) than individuals with the highest risk profile.[Citation17] In our study, all patients were hypertensive and on antihypertensive treatment, and smoking and cholesterol were not identified as an important predictors of cardiac morbidity.

The WHO expects an almost exponential increase in diabetics [Citation6] and the main focus should be on primary prevention. The key to prevent cardiovascular complications is to focus on optimizing risk factors such as blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, diabetes and smoking cessation. In the general population, women are at lower risk than men for cardiovascular disease; however, women with diabetes have a disproportionately greater increase in the risk for cardiovascular disease than men with diabetes.[Citation18] The reason for this is not known, but is likely to be multifactorial with contributions from inherited physiological differences, differences in cardiovascular risk factors, and differences in behaviour and physical activities between the genders.[Citation18]

In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial, intensive blood pressure treatment (target systolic blood pressure < 120 mmHg) did not significantly reduce the primary composite endpoint (myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death) compared to standard treatment (target systolic blood pressure < 140 mmHg).[Citation19] However, ACCORD was underpowered owing to the modest number of participants and multiple interventions to prevent disease. Thus, the finding that low diastolic blood pressure predicted cardiac morbidity in the diabetic groups in the present analysis is likely to be explained by reversed causality, i.e. patients with low diastolic blood pressure are sicker than others. This is rather strongly supported by a concomitant VALUE analysis showing that the so-called “J curve” between blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular events was no longer present after statistical adjustment for baseline diseases and measures of organ damage.[Citation20]

Body mass index was also a significant predictor in the patients with diabetes at baseline but not a significant predictor in the subgroup without diabetes. This may be due to cardiovascular morbidity in patients with diabetes being more linked to the metabolic syndrome [Citation21] and clustering of risk factors (central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes) than in patients without diabetes.[Citation13]

The main outcome of cardiac disease did not differ between the treatment groups (amlodipine/valsartan) in the VALUE trial,[Citation10] and study therapy was not a significant predictor in any of the univariate and multivariate analyses.

This secondary analysis had some limitations. Known cardiovascular risk factors such as physical fitness and physical activity, as well as family history of cardiovascular disease, were not registered in the VALUE trial database. Despite a rather high number of patients who developed new-onset diabetes (n = 1298), the study was underpowered to assess predictors of events in this group by forward stepwise regression. However, we still put emphasis on the findings because of the confirmation in the full multivariate model and consistency with the findings in the other groups. It may not be considered exciting to prove that already existing cardiac disease predicts new or worsening cardiac disease; however, the impact of history of coronary disease in this population was in competition with a number of other well-described and important risk and disease factors. Cardiac mortality is not included in our analyses of predictors, as it is difficult to compare mortality events between patients with new-onset diabetes and the other patients, as explained earlier. Neither is stroke included in our analyses of predictors, partly because of consistency with previous work [Citation13,Citation22] and partly because stroke is a different disease which may require separate analysis.[Citation23]

In conclusion, diabetic and new-onset diabetic hypertensive patients in the VALUE trial had higher cardiac morbidity than patients without diabetes. However, predictors of cardiac morbidity were essentially the same in both patients with and those without diabetes. History of CHD and age were consistently the most important predictors of cardiac morbidity in both patients with diabetes and those without diabetes.

ID__IBLO_1134071._Aksnes_et_al._Supplementary_Tables_I-IV.docx

Download MS Word (21.8 KB)Aksnes_et_al._Supplementary_material_revised.docx

Download MS Word (21.7 KB)Disclosure statement

T.A.A. has no interest to declare. S.E.K., M.R. and S.J. were members of the Steering Committee in the VALUE trial. B.H. and T.A.H. are employees of Novartis, the sponsor of the VALUE trial.

References

- Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421.

- Juutilainen A, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, et al. Type 2 diabetes as a “coronary heart disease equivalent”: an 18-year prospective population-based study in Finnish subjects. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2901–2907.

- Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434–444.

- Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–234.

- Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Solomon CG, et al. The impact of diabetes mellitus on mortality from all causes and coronary heart disease in women: 20 years of follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1717–1723.

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. Fact sheet no. 312. Geneva: WHO; 2011. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/.

- Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: the Framingham study. Circulation. 1979;59:8–13.

- Chen G, McAlister FA, Walker RL, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in Framingham participants with diabetes: the importance of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2011;57:891–897.

- Alderman MH, Cohen H, Madhavan S. Diabetes and cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1999;33:1130–1134.

- Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2022–2031.

- Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Mancia G, et al. Effects of valsartan compared to amlodipine on preventing type 2 diabetes in high-risk hypertensive patients: the VALUE trial. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1405–1412.

- Barzilay JI, Davis BR, Cutler JA, et al. Fasting glucose levels and incident diabetes mellitus in older non-diabetic adults randomized to receive 3 different classes of antihypertensive treatment: a report from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2191–2201.

- Aksnes TA, Kjeldsen SE, Rostrup M, et al. Impact of new-onset diabetes mellitus on cardiac outcomes in the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial population. Hypertension. 2007;50:467–473.

- Sui X, Hooker SP, Lee IM, et al. A prospective study of cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:550–555.

- Carnethon MR, Sternfeld B, Schreiner PJ, et al. Association of 20-year changes in cardiorespiratory fitness with incident type 2 diabetes: the Coronary Artery Risk Development In young Adults (CARDIA) fitness study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1284–1288.

- Mann J, Julius S. The Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial of cardiovascular events in hypertension. Rationale and design. Blood Press. 1998;7:176–183.

- Berry JD, Dyer A, Cai X, et al. Lifetime risks of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:321–329.

- Miller TM, Gilligan S, Herlache LL, Regensteiner JG. Sex differences in cardiovascular disease risk and exercise in type 2 diabetes. J Investig Med. 2012;60:664–670.

- Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585.

- Kjeldsen SE, Berge E, Bangalore S, et al. No evidence for a J-curve shaped curve in treated hypertensive patients with increased cardiovascular risk: the VALUE trial. Blood Press. 2016;24. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08037051.2015.1106750.

- Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645.

- Aksnes TA, Rostrup M, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Predictors of diabetes in high risk hypertensive patients in the VALUE trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22:520–527.

- Sandset EC, Krarup L-H, Berge E, et al. Heart rate as a predictor of recurrent stroke in a hypertensive population with previous stroke or transient ischemic attacks. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2814–2818.