Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between 24 h blood pressure (BP) profile, extent of significant coronary artery stenosis, confirmed by coronary angiography, and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Coronary angiographies were performed for all included subjects and significant coronary artery stenosis was considered as ≥ 50% stenosis by atherosclerotic plaque. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory BP monitoring was performed. Major advanced cardiovascular events (MACE) included revascularization, cardiovascular mortality, total mortality, acute coronary syndromes and stroke. BP analysis revealed higher night-time systolic blood pressure (SBP) values in patients with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses than in those without significant stenosis (120.7 ± 16.4 vs 116.7 ± 14.3 mmHg, p < 0.001), lower night-time SBP dip in patients with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses than in those without significant stenosis (5.7 ± 3.2 vs 7.4 ± 6.8 mmHg, p < 0.001) and lower night-time diastolic blood pressure dip in patients with three or more significant stenoses than in patients without significant stenosis (9.4 ± 7.4 vs 11.9 ± 7.4 mmHg, p < 0.001). Night-time SBP values, night-time/daytime SBP dip and extent of significant coronary artery stenosis were risk factors for MACE, revascularization and cardiovascular mortality. In conclusion, the study shows that advanced coronary artery disease is related to blunted night-time BP dipping and cardiovascular complications.

Introduction

The development of coronary atherosclerosis is related to the impact of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.[Citation1] Elevated blood pressure (BP) values are one of the most well-known and frequent cardiovascular risk factors leading to coronary artery stenosis development. However, less is known about the association between BP variability and coronary atherosclerosis progression.

In a study on a small group of men with coronary artery disease, a relationship between blunted nocturnal BP fall and coronary atherosclerosis was confirmed.[Citation2] Other studies showed that impaired night-time BP drop was a risk factor for cardiovascular events even in patients with normal office BP values.[Citation2] Despite the substantial progress of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy for hypertension there are patients with a high cardiovascular risk due to inappropriate BP control. Moreover, even patients with normal BP values may experience a higher cardiovascular risk because of impaired 24 h BP control. Subjects with abnormal diurnal BP control and coexisting coronary atherosclerosis seem to be particularly exposed to cardiovascular events.[Citation3] In most large clinical trials for hypertension, pharmacotherapy has been established on the basis of office BP values, but some substudies with 24 h BP monitoring have confirmed that abnormal nocturnal BP regulation may be associated with cardiovascular disorders leading to the development of cardiovascular complications.

Taking into consideration well-known findings from previous studies, we hypothesized that impaired BP nocturnal fall may be associated with coronary atherosclerotic plaque extent and may be a cardiovascular risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease. Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess the relationship between 24 h BP profile, extent of significant coronary artery stenosis, confirmed by coronary angiography, and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease.

Material and methods

Subjects

Between August 2003 and August 2006, the study included 1345 subjects with effort angina symptoms and/or signs of myocardial ischaemia confirmed by non-invasive diagnostic procedures (electrocardiogram stress test, dobutamine stress echocardiography or myocardial perfusion scintigraphy stress test). The exclusion criteria included supraventricular arrhythmias, i.e. atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, congestive heart failure of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV, significant valvular heart disease or valvular heart disease qualifying the patient for cardiosurgery, renal insufficiency with a creatinine level ≥ 2.0 mg/dl and other chronic diseases leading to limited life expectancy, as well as changes in the pharmacotherapy for hypertension within a period of 6 months before 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM).

Blood pressure measurements

Office BP measurements were performed on the non-dominant arm using a validated oscillometric device (OMRON 705 IT) with the cuff fitted to arm circumference.

Twenty-four-hour ABPM was performed (SpaceLabs 90210; SpaceLabs, Redmond, WA, USA) with BP readings set at 20 min intervals (06:00 –18:00 h) and at 30 min intervals (18:00 h–06:00 h) in a period of 2–4 weeks after coronary angiography to avoid the need for reduced physical activity owing to hospital conditions. The cuff size was adjusted to arm circumference. Measurements were obtained on the non-dominant arm. BP measurements were recorded between 08:00 h and 22:00 h (daytime BP values) and between 00:00 h and 06:00 h (night-time BP values). Night-time/daytime BP dip was calculated as 100 × [(Daytime SBP mean – Night-time SBP mean)/Daytime SBP mean]. This classification was performed for systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) for each included patient.

Antihypertensive therapy

All participants were treated with antihypertensive drugs. Pharmacological therapy was scheduled by general practitioners or cardiologists who were involved in the subjects’ treatment for hypertension. Decisions about the pharmacotherapy for hypertension were made on the basis of office BP values. All the doctors had European Society of Hypertension guidelines at their disposal.

Laboratory tests

During the inclusion visit, fasting blood samples were collected to measure creatinine, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

Assessment of coronary atherosclerosis

Coronary angiographies were performed in the Department of Invasive Cardiology and angiograms were evaluated independently by two experienced invasive cardiologists. Significant coronary artery stenosis was considered as ≥ 50% coronary artery stenosis by atherosclerotic plaque.

Follow-up period

Subjects were followed from the date of the inclusion visit until 31 December 2013. Follow-up was performed during control clinic visits, and if patients were unable to attend they were contacted by telephone. Stroke diagnosis was performed according to European Stroke Organization guidelines and acute coronary syndromes (ACS) were diagnosed according to European Society of Cardiology guidelines. Cardiovascular mortality included events due to ACS (myocardial infarction or unstable angina), heart failure and stroke. Revascularizations involved percutaneous coronary angioplasty and/or coronary bypass grafting. During the follow-up period, four outcomes were studied: revascularization; cardiovascular mortality; total mortality; and major advanced cardiovascular events (MACE), including ACS and stroke.

Statistical analysis

The overarching goal of the analysis was to create a relationship between diurnal profile of BP, extent of significant coronary artery stenosis and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. To compare continuous variables, a Student’s t test or a Mann–Whitney U test was used as appropriate. For categorical variables, a chi-squared test was used. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine the association between significant coronary artery stenosis extent, BP values and BP dipping risk of MACE, revascularization, cardiovascular mortality and total mortality after adjustment for age, gender, diabetes, smoking and LDL-cholesterol level, and additionally for daytime SBP and DBP and night-time SBP and DBP for significant coronary artery stenosis extent. The time to MACE, revascularization, cardiovascular death or all-cause death was determined from the baseline date to the date of these events. The significance of individual coefficients in the Cox proportional hazards model was determined by hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. In other analyses, continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD and categorical variables as percentages. A value of p < 0.05 was taken as the level of statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using STATISTICA version 10 (Tulsa, OK) and R version 3.0.1.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Gdansk.

Results

From consecutive patients with coronary heart disease admitted for coronary angiography, 1908 met the inclusion criteria. After considering the exclusion criteria, 1345 subjects (525 female and 820 male, mean age 63.4 ± 10.9 years) were finally included in the present study. We excluded 563 patients (28%) in total owing to the following conditions: supraventricular arrhythmias (n = 138, 7%), symptomatic congestive heart failure of NYHA class III or IV (n = 97, 5%), significant valvular heart disease or valvular heart disease qualifying the patient for cardiosurgery (n = 123, 6%), renal insufficiency with a creatinine level ≥ 2.0 mg/dl (n = 83, 4%) and other chronic diseases leading to limited life expectancy (n = 122, 6%). The characteristics of the study participants included in the current analysis are presented in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study group.

Taking into account coronary atherosclerosis extent, the total group of subjects was divided into three subgroups: patients without significant coronary artery stenosis (n = 454, 34% of total group), patients with one or two coronary artery stenoses (n = 563, 42% of total group) and patients with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses (n = 328, 24% of total group). BP values in the study subgroups are presented in Supplementary Table SI (see online supplement).

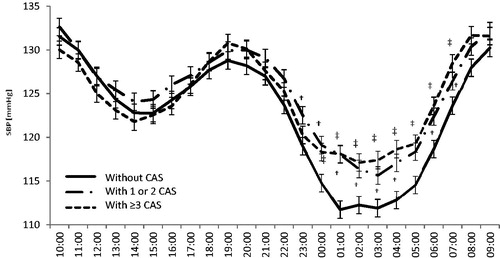

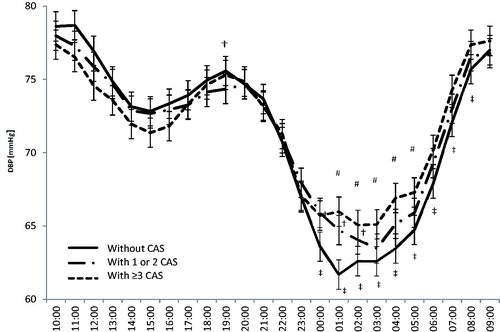

Analysis of outcomes revealed a higher prevalence of MACE, revascularization, cardiovascular mortality and total mortality in patients with three or more coronary artery stenoses in comparison to subjects without significant coronary artery stenosis (Supplementary Table SI). Analysis of 24 h BP distribution revealed significantly lower mean hourly night-time SBP values between 00:00 h and 07:00 h in subjects without significant coronary artery stenosis in comparison to subjects with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses. During these hours, there was a significant difference in mean SBP between the subgroup without significant coronary artery stenosis and the subgroup with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses (116.4 ± 14.6 mmHg vs 121.3 ± 16.2 mmHg, p < 0.001). The highest difference between these subgroups was observed at 01:00 h (111.7 ± 16.1 mmHg vs 118.1 ± 19.0 mmHg, p < 0.001). Analysis of 24 h DBPs revealed significantly lower night-time DBP values between 00:00 h and 08:00 h in subjects without significant coronary artery stenosis in comparison to subjects with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses. During these hours, there was a significant difference in mean DBP between the subgroup without significant coronary artery stenosis and the subgroup with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses (66.0 ± 8.8 mmHg vs 68.6 ± 9.0 mmHg, p < 0.001). The highest difference between these subgroups was observed at 01:00 h (61.7 ± 10.3 mmHg vs 64.7 ± 11.5 mmHg, p < 0.001).

Hourly night-time DBP values between 01:00 h and 05:00 h showed lower mean DBPs in subjects with one or two significant coronary artery stenoses in comparison to subjects with three or more significant coronary artery stenoses ( and ). The Cox proportional hazards model revealed that night-time SBP and night-time/daytime dip were risk factors for MACE, revascularization and cardiovascular mortality. Furthermore, there was a relationship between the number of significant coronary artery stenoses and MACE, revascularization, and cardiovascular and total mortality (Supplementary Table SII).

Discussion

The key finding of our study is the confirmation of higher night-time SBP values and lower night-time SBP and DBP dip in patients with at least one significant coronary artery stenosis than in patients without significant coronary artery stenosis. We also found that night-time SBP values, night-time/daytime SBP dip and significant coronary artery stenosis extent were risk factors for MACE, revascularization and cardiovascular mortality.

Clinical studies on hypertension have confirmed that elevated BP is a risk factor for cardiovascular events. However, in most of these studies office BP values were recorded during the daytime period. Only some studies with ABPM have revealed that night-time BP values correlated more closely with clinical events than did office BP values.[Citation4] Fan et al. confirmed that an increase in night-time BP values of 1 SD was related to a 20% increase in cardiovascular events such as stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure and revascularization.[Citation5] Moreover, Kario et al. found that blunted night-time BP was related to myocardial ischaemia at night.[Citation6] In the present study, we confirmed that elevated night-time SBP was a risk factor for MACE, revascularization and cardiovascular mortality, but there was no significant relationship between either daytime or office BP and cardiovascular endpoints.

Previously performed clinical trials have revealed that blunted night-time BP decrease is related to either subclinical target organ damage as a prognostic marker for future cardiovascular events or clinical cardiovascular complications.[Citation3,Citation7] In our study, night-time/daytime SBP dip was related to MACE, revascularization and cardiovascular mortality. Similarly, in the PIUMA study, performed in hypertensive patients, there was a higher risk of cardiovascular events in patients with blunted night-time BP decrease in comparison to those with normal nocturnal BP fall. This finding was confirmed over a median of 3.2 years of observation.[Citation8]

In our study, MACE, revascularization and cardiovascular mortality were more frequent in groups of subjects with significant coronary artery stenosis than in those without significant coronary artery stenosis. Moreover, significant coronary artery stenosis extent was a risk factor for MACE, revascularization, cardiovascular mortality and total mortality. Furthermore, patients with the most advanced significant coronary artery stenosis had significantly higher night-time SBP and DBP values. Mousa et al. revealed higher night-time SBP and DBP values in men with coronary atherosclerotic plaques, but there were no differences in office BP values between patients with significant coronary atherosclerosis (assessed as coronary artery stenosis ≥ 70%) and patients without coronary atherosclerosis.[Citation2] On the other hand, Turner et al. found both higher daytime BP values and higher night-time BP values in patients with at least one coronary artery sclerosis ≥ 50% assessed by computed tomography.[Citation9] The different findings between the present study and the study by Turner et al. may result from the younger participants involved in the study by Turner et al. (mean age 40 ± 9 years) and the lower specificity of coronary artery stenosis assessment (72% for computed tomography for 50% coronary artery stenosis). In a study by Sherwood et al., postmenopausal women with established coronary artery disease (defined by cardiac catheterization documenting ≥ 50% occlusion of at least one major coronary vessel) had blunted night-time BP dipping.[Citation10] As in our study, in the absence of differences in office SBP and DBP between subjects with coronary artery disease and those without coronary artery disease, the latter group had a significantly lower night-time SBP. Although only women were recruited for the study, they had amenorrhoea for at least 1 year before inclusion in the study, so the protective effects of female reproductive hormones were limited.[Citation10]

The limitations of the present study include the cross-sectional design, which precludes inferences regarding the causality of the relationship between BP dipping and coronary artery disease. In view of the evidence that night-time BP dipping may have limited reproducibility, we also note that our findings are based on a single, unrepeated 24 h ABPM record for each participant.[Citation11] Because none of the participants was a shift worker, we did not take into consideration disturbances of sleep or possible night-time activity in some participants. However, analysis of heart rate during the night in all participants did not reveal significant surges that could indicate substantial night-time activity during night-time BP measurements.

In summary, this observational study shows that advanced coronary artery disease is related to blunted night-time BP dipping and cardiovascular complications. Moreover, night-time SBP values, night-time SBP dipping and significant coronary artery stenosis are related to cardiovascular complications. Our findings also draw attention to the high prevalence of abnormal night-time BP values in subjects with the most advanced coronary artery disease, and suggest a need to take this cardiovascular risk factor into consideration in the treatment of patients with coexisting coronary artery disease and hypertension.

Table__S2_and_S3.docx

Download MS Word (17.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, et al. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease – six year follow-up experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33–50.

- Mousa T, el-Sayed MA, Motawea AK, et al. Association of blunted nighttime blood pressure dipping with coronary artery stenosis in men. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:977–980.

- Pierdomenico SD, Bucci A, Costantini F, et al. Circadian blood pressure changes and myocardial ischemia in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1627–1634.

- Kario K, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG. Changes of nocturnal blood pressure dipping status in hypertensives by nighttime dosing of alpha-adrenergic blocker, doxazosin: results from the HALT study. Hypertension. 2000;35:787–794.

- Fan HQ, Li Y, Thijs L, et al. Prognostic value of isolated nocturnal hypertension on ambulatory measurement in 8711 individuals from 10 populations. J Hypertens. 2010;28:2036–2045.

- Kario K, Matsuo T, Kobayashi H, et al. Nocturnal fall of blood pressure and silent cerebrovascular damage in elderly hypertensive patients. Advanced silent cerebrovascular damage in extreme dippers. Hypertension. 1996;27:130–135.

- Cicconetti P, Morelli S, Ottaviani L, et al. Blunted nocturnal fall in blood pressure and left ventricular mass in elderly individuals with recently diagnosed isolated systolic hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:900–905.

- Verdecchia P, Porcellati C, Schillaci G, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure. An independent predictor of prognosis in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1994;24:793–801.

- Turner ST, Bielak LF, Narayana AK, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure and coronary artery calcification in middle-aged and younger adults. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:518–524.

- Sherwood A, Bower JK, Routledge FS, et al. Nighttime blood pressure dipping in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:1077–1082.

- Manning G, Rushton L, Donnelly R, et al. Variability of diurnal changes in ambulatory blood pressure and nocturnal dipping status in untreated hypertensive and normotensive subjects. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:1035–1038.