Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is common in solid organ transplant recipients and accounts for the majority of graft compromise. Major risk factors include primary exposure to CMV infection at the time of transplantation and the use of antilymphocyte agents such as OKT3 (the monoclonal antibody muromonab-CD3) and antithymocyte globulin. It most often develops during the first 6 months after transplantation. Although current prophylactic strategies and antiviral agents have led to decreased occurrence of CMV disease in early posttransplant period, the incidence of late-onset CMV disease ranges from 2% to 7% even in the patients receiving prophylaxis with oral ganciclovir. The most common presentation of CMV disease in transplant patients is CMV pneumonitis followed by gastrointestinal disease. Hemorrhagic cystitis is a common complication following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The condition is usually due to cyclophosphamide-based myeloablative regimens and infectious agents. Even in these settings, CMV-induced cases occur only sporadically. Ureteritis and hemorrhagic cystitis due to CMV infection after kidney transplantation is reported very rarely on a case basis in the literature so far. We report here a case of late-onset CMV-induced hemorrhagic cystitis and ureteritis presenting with painful macroscopic hematuria and ureteral obstruction after 4 years of renal transplantation. The diagnosis is pathologically confirmed by the demonstration of immunohistochemical staining specific for CMV in a resected ureteral section. We draw attention to this very particular presentation of CMV hemorrhagic cystitis with ureteral obstruction in order to emphasize atypical presentation of tissue-invasive CMV disease far beyond the timetable for posttransplant CMV infection.

INTRODUCTION

The risk of viral infection in transplant patients is determined by complex interactions of patient-, graft-, and virus-specific factors that are modulated by the net state of immunosuppression. It is highest during the first few months after transplantation, when the patient is still under high levels of immunosuppression. Infections during this high-risk period are not uniform but follow a typical time schema.Citation1 Typical opportunistic infections, most importantly cytomegalovirus (CMV), emerge after 1-month posttransplantation while surgical infections decrease.Citation2 The rate of posttransplant CMV infection ranges from 20% to 85%, antithymocyte globulin (ATG) use being an independent risk factor, and despite antiviral prophylaxis the incidence of late-onset CMV disease still remains as high as 7%, and the majority of these cases have tissue-invasive disease.Citation3–5 There are sporadic cases of reported CMV-induced hemorrhagic cystitis (especially following bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) and ureteritis after solid organ transplantation in the literature so far.Citation6–12 However, to our best knowledge, there is no previously reported late-onset CMV-induced, simultaneous hemorrhagic cystitis and ureteritis case after renal transplantation.

THE CASE

A 53-year-old man seropositive for CMV (R+) underwent cadaveric kidney transplant from seropositive donor (D+) 4 years ago. As induction therapy, interleukin 2 receptor antagonist basiliximab was given. Cold ischemia time was 6 h. The patient received oral acyclovir prophylaxis and immunosuppression with cyclosporine, prednisone, and mycophenolic acid. On day 10 of transplantation, because of urinary leakage ureteroneocystostomy was performed and protected by a double-J stent. The allograft function remained stable at creatinine levels ranging from 1.12 to 1.26 mg/dL during a 4-year follow-up period, and the stent was removed 1 month later.

On his fourth year after transplantation, he presented with 3-day painful gross hematuria, lower abdominal pain, fever, and dysuria and was admitted to the hospital. The patient looked septic with a fever of 38.7°C without any other revealing physical examination findings. The laboratory tests showed leukocyte count of 19,700/mm3, hemoglobin level of 8.4 g/dL, and creatinine level of 7.2 mg/dL. Liver function tests were normal. The urine analysis revealed pyuria and hematuria. He was hydrated vigorously and initially treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. He also underwent hemodialysis on 2 consecutive days. Cultures of urine were negative for bacteria. Screening for BK virus inclusions (decoy cells) in the urine was also negative. An ultrasound of transplant kidney showed dilatation of collecting systems. Abdominal tomography without contrast injection also revealed pelvicalyceal dilatation with increased wall thickness of ureter but without any obstructive lesions. Meanwhile, the patient continued to have painful macroscopic hematuria attacks. Anterograde pyelography demonstrated distal ureteral stenosis, and a ureteral double-J stent and a percutaneous nephrostomy catheter were placed (). Creatinine levels gradually decreased to 2.2 mg/dL on day 19. The urine cytology was reported to include inclusion bodies suggestive of CMV. The patient had no other signs of CMV infections for the time being and also during the follow-up period. He had no monitoring for CMV presence and activity beyond first year of transplantation. Within first year, we did not detect positivity of pp65 antigenemia that was checked with monthly intervals during first 6 months and three monthly thereafter.

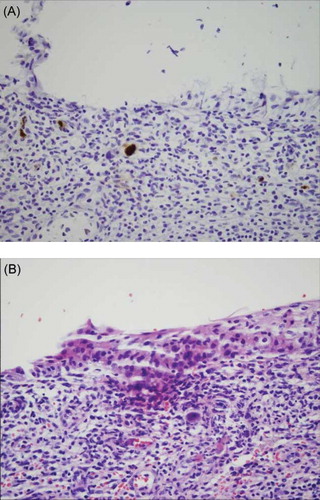

On day 20, cystoscopy was performed. The bladder epithelium appeared erythematous and fragile. Examination of biopsy specimens showed the presence of intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions in endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages consistent with CMV. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CMV (A). SV40 staining for polyoma virus was negative. The diagnosis of CMV cystitis was made and the patient was instituted treatment with intravenous ganciclovir. One week later, fibrosed stenotic distal ureteral segment was resected and re-ureteroneocystostomy was performed. Pathological examination revealed ulcerated tissue with chronic inflammation and fibrosis and CMV-positive endothelial cells. CMV ureteritis was diagnosed (B). The patient was treated with i.v. ganciclovir for 21 days. He has already well-functioning graft with creatinine level of 1.35 mg/dL with no recurrence of CMV disease.

DISCUSSION

CMV belongs to human herpes viruses, and characteristically it establishes latency primarily in CD34+ myeloid progenitor cells following primary replication in seronegative individuals. The seroprevalence depending on socioeconomic status ranges from 30% to 70% in Western Europe.Citation1 It is a significant o0pportunistic pathogen in transplant patients.

The risk of viral infection in transplant patients is determined by complex interactions of patient-, graft-, and virus-specific factors that are modulated by the net state of immunosuppression. It is highest during the first few months after transplantation, when the patient is still under high levels of immunosuppression. Infections during this high-risk period are not uniform but follow a typical time schema. CMV infections are common after 1 month when typical opportunistic infections begin to emerge. CMV-seronegative recipients (R–) transplanted from CMV-seropositive donors (D+) are at highest risk for CMV replication and disease. The risk of infection is also increased in CMV (R+) patients by the use of T-cell depleting agents (ATG) for rejection since cellular immunity is central in controlling CMV replication.Citation1–3

The case presented was initially considered to be in a low-risk status for CMV infection as he had R+ status and had no additional risk factors such as acute rejection, use of ATG, or pulse steroid. Therefore, as a center protocol, considering the cost issues as well, we used a less-efficient anti-CMV prophylactic drug (acyclovir) for antiviral prophylaxis. Although antiviral prophylaxis has effectively prevented CMV disease in the early posttransplant period, the incidence of late-onset CMV disease still remains as high as 7%, and the majority of these cases have tissue-invasive disease.Citation4

Hemorrhagic cystitis can be seen in almost 70% of bone marrow transplant patients and usually occurs within 48 h after high-dose cyclophosphamide therapy. However, late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis after transplantation is usually due to viral infections, especially polyomavirus (BK and JC virus), and less frequently adenovirus and herpes simplex virus.Citation5,6 CMV reactivation was found to be associated with late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.Citation7 There are sporadic case reports of CMV ureteritis as an emerging cause of ureteral obstruction that occurred within 6 months after kidney transplantation.Citation8–13 Most of those patients did not have systemic signs or symptoms suggestive of CMV infection. The patient presented lacked the classical symptoms of CMV disease. He was unsuspectedly proven to have tissue-invasive CMV disease. We did not initially employ any method of routine surveillance for CMV infection in this case, and possibly this might prevent early diagnosis. Our patient differs from previously reported ones with respect to the time of occurrence and having two clinical spectrum of CMV disease (hemorrhagic cystitis and ureteritis) simultaneously.

This unique case is presented to emphasize the need to be aware of atypical manifestations of late-onset CMV disease in a renal transplant recipient. Intravenous ganciclovir therapy is effective in this setting. The need for extension of anti-CMV prophylaxis in terms of oral valganciclovir to seropositive renal transplant recipients may be revised based on large-scale studies.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Egli A, Binggeli S, Bodaghi S, . Cytomegalovirus and polyomavirus BK posttransplant. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(Suppl. 8):72–82.

- Issa NC, Fishman JA. Infectious complications of antilymphocyte therapies in solid organ transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(6):772–786.

- Taherimahmoudi M, Ahmadi H, Baradaran N, . Cytomegalovirus infection and disease following renal transplantation: Preliminary report of incidence and potential risk factors. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(7):2841–2844.

- Kalil AC, Levitsky J, Lyden E, Stoner J, Freifeld AG. Meta-analysis: The efficacy of strategies to prevent organ disease by cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(12):870–880.

- Tutuncuoglu SO, Yanovich S, Ozdemirli M. CMV-induced hemorrhagic cystitis as a complication of peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: Case report. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36(3):265–266.

- Spach DH, Bauwens JE, Myerson D, Mustafa MM, Bowden RA. Cytomegalovirus-induced hemorrhagic cystitis following bone marrow transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(1):142–144.

- Xu LP, Zhang HY, Huang XJ, . Hemorrhagic cystitis following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Incidence, risk factors and association with CMV reactivation and graft-versus-host disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120(19):1666–1671.

- Lowell JA, Stratta RJ, Morton JJ, Kolbeck PC, Taylor RJ. Invasive cytomegalovirus infection in a renal transplant ureter after combined pancreas-kidney transplantation: An unusual cause of renal allograft dysfunction. J Urol. 1994;152(5 Pt 1):1546–1548.

- Moudgil A, Germain BM, Nast CC, Toyoda M, Strauss FG, Jordan SC. Ureteritis and cholecystitis: Two unusual manifestations of cytomegalovirus disease in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1997;64(7):1071–1073.

- Vongwiwatana A, Vareesangthip K, Vasuvattakul S, . Ureteritis due to cytomegalovirus infection in renal transplant recipient: A case report. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(7):1927.

- Leikis MJ, Denford AJ, Pidgeon GB, Hatfield PJ. Post-renal transplant obstruction caused by cytomegalovirus ureteritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(12):2063–2064.

- Thomas MC, Russ GR, Mathew TH, Rao Mohan M, Cooper J, Walker RJ. Four cases of CMV ureteritis: Emergence of a new pattern of disease? Clin Transplant. 2001;15(5):354–358.

- Vaessen C, Kamar N, Mehrenberger M, . Severe cytomegalovirus ureteritis in a renal allograft recipient with negative CMV monitoring. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(1):227–230.