Abstract

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used by patients all over the world. Five to eighteen percent of the patients who receive NSAIDs can suffer from kidney-related side effects. Among them, the most relevant are sodium and water retention, hyponatremia, worsening of hypertension or preexisting cardiac failure, hyperkalemia, acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, papillary necrosis, nephrotic syndrome (NS), and acute interstitial nephritis. We report the case of a 65-year-old woman who developed acute tubular necrosis and NS a few days after receiving 15 mg of meloxicam (MLX) for 3 days for tendinitis. Steroid therapy was begun with normalization of kidney function after 7 weeks of treatment. NS (minimal change disease) was characterized by frequent remissions and relapses as prednisone was lowered under 30 mg/day. Azathioprine (100 mg/day) was added on the fifth month of diagnosis and a complete remission was finally obtained 4 years after hospital admittance. In her last medical checkup, 8 years after her debut and receiving azathioprine (50 mg) and prednisone (5 mg/day), renal function was normal (creatinine 1.0 mg/dL and creatinine clearance 80 mL/min/1.73 m2), proteinuria was 150 mg/day and there was no hematuria or hypertension.

The aim of communicating this case is to raise a warning about these renal side effects of MLX. After thorough review of literature, only one other report with the same findings was found.

INTRODUCTION

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used by patients all over the world, either by medical or by self-prescription. Five to eighteen percent of the patients who receive NSAIDs can suffer from kidney-related side effects.Citation1,2 Among them, the most relevant are sodium and water retention with edema, hyponatremia, worsening of hypertension or pre-existing cardiac failure, hyperkalemia, acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic kidney disease, papillary necrosis, nephrotic syndrome (NS), and acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).Citation3–6 The association of the latter two conditions in the same patient and of NS with acute tubular necrosis has been described with the use of different NSAIDs, although the reports are scarce.Citation7,8

We describe a case of NS associated with acute tubular necrosis in a patient who received meloxicam (MLX) for 3 days. After thorough review of literature, only one other report with the same findings was found.Citation9

CLINICAL CASE

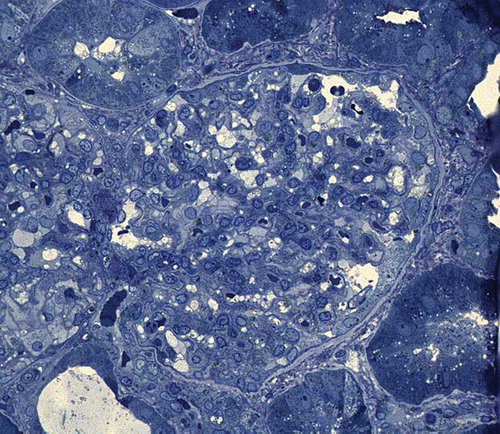

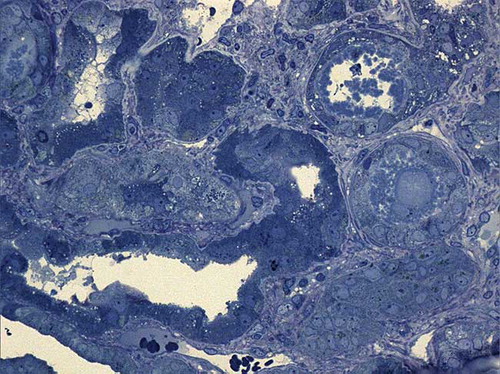

A 65-year-old woman, without relevant comorbidities, developed edema, oliguria, bilateral lumbar pain, nausea, and vomiting a few days after receiving 15 mg/day of MLX for 3 days as a pain relief treatment for tendinitis of the forearm. One week after the beginning of symptoms, she was admitted to hospital because of anasarca. At initial clinical evaluation, she was afebrile, her blood pressure was 190/97 mmHg, and her cardiac rate was 92 beats per minute. Laboratory results showed anemia (hematocrit 33%), leukocytosis (10,600 per mm3) without eosinophilia, thrombocytosis (556,000 per mm3), high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (110 mm/hour), renal failure [blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 73.8 mg/dL, serum creatinine 8.4 mg/dL, creatinine clearance 11 mL/min/1.73 m2], hyponatremia (131 mEq/L), metabolic acidosis (HCO3− 13.9 mEq/L), microscopic hematuria, proteinuria, and granular casts in the urine sediment. Serum calcium was 8.0 mg/dL, potassium 4.8 mEq/L, and phosphorus 9.6 mg/dL. Antinuclear antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative, and C3 and C4 levels were normal. Ultrasonography showed normal-sized kidneys with diffuse increase in their echogenicity. AIN secondary to NSAIDs use was clinically diagnosed. Steroid therapy (100 mg of hydrocortisone i.v. t.i.d.) was begun, and a percutaneous renal biopsy was performed. Light microscopy examination showed 11 glomeruli, all of them with normal architecture () and severe tubular injury compatible with acute tubular necrosis (). There was no evidence of any proliferative changes, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, or severe interstitial edema. Immunofluorescence examination did not demonstrate immunoglobulin or complement deposits. Electron microscopy analysis revealed severe foot process effacement of visceral epithelial cells, compatible with a diffuse form of podocyte injury in the context of minimal change disease. There were no dense deposits in the glomerular basement membrane, ruling out membranous glomerulopathy (). Urine output of less than 1000 mL/day was observed for the first 4 days, improving over time. Treatment was continued using 60 mg/day of prednisone, furosemide, and atorvastatin, adding enalapril after initial recovery. The patient was discharged after 28 days from hospital admission, persisting with clinical findings compatible with NS (proteinuria 3460 mg/day, serum protein 4.4 g/dL, serum albumin 2.2 g/dL, cholesterol 564 mg/dL, and triglycerides 318 mg/dL) and with partial recovery of renal function (serum creatinine 1.8 mg/dL, creatinine clearance 35 mL/min/1.73 m2, and BUN 74.8 mg/dL).

Figure 1. Light microscopic examination. Glomerulus (center of image) and an adjacent segment. Mesangiocapillary architecture is preserved (Toluidine blue ×400).

Figure 2. Light microscopic examination. Tubulointerstitial area. The proximal tubules showed epithelial flattening, loss of brush border, and intraluminal necrotic debris (toluidine blue ×400).

Figure 3. Glomerular ultrastructure. Podocytes show diffuse effacement of podocytes with cytoplasmic microvillous transformation zones compatible with minimal change disease (uranyl acetate, lead citrate ×11.600).

Three weeks after leaving the hospital, it was found that azotemia had disappeared (serum creatinine 1.0 mg/dL, BUN 12.6 mg/dL) and NS was in complete remission—only traces of proteinuria, serum protein (6.6 g/dL), albumin (3.6 g/dL), cholesterol (238 mg/dL), and triglycerides (167 mg/dL) were found. Diuretics and enalapril were withdrawn and prednisone was reduced to 40 mg/day.

The following months and years were characterized by frequent remissions and relapses of NS as prednisone was lowered under 30 mg/day. Azathioprine (100 mg/day) was added on the fifth month of diagnosis, and a complete remission was finally obtained 4 years after hospital admittance. During follow-up, there were no clinical or radiologic evidence of malignancies that could explain minimal change disease.

In her last medical checkup, 8 years after her debut and receiving azathioprine (50 mg) and prednisone (5 mg/day), renal function was normal (creatinine 1.0 mg/dL and creatinine clearance 80 mL/min/1.73 m2), proteinuria was 150 mg/day, and there was no hematuria or hypertension.

DISCUSSION

Traditional NSAIDs, as well as selective cyclooxigenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, can cause undesired side effects in the kidneys.Citation1,3 These can be secondary to the inhibition of prostaglandin (PG) synthesis or hypersensitivity mechanisms.Citation3

In patients with normal renal function and basal conditions, the renal synthesis of PG is low, and it does not play a significant role in the maintenance of intrarenal hemodynamics.Citation10 Nevertheless, in situations of decreased renal perfusion such as hypovolemia or reduced cardiac output, the local synthesis of vasodilator PG (prostacyclin and PGE2) is increased resulting in protection of glomerular hemodynamics and keeping appropriate tubular transport of liquids and electrolytes. Blocking PG synthesis produces vasoconstriction, which can lead to AKI.Citation5,10 The patients with greater risk of undergoing these effects are the ones presenting with coexistent cardiopathies, hepatic disease, and chronic kidney disease, diuretic users, and the elderly with vascular damage or gout.Citation3,4 The prolonged use of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors can also lead to subclinical renal damage, such as reduction in creatinine clearance and/or impairment of concentration ability, which are generally reversible but can be persistent in selected cases.Citation11

The association of NS with AIN is infrequent, but it has been described with the use of NSAIDs as well as with selective COX-2 inhibitorsCitation12—such as diclofenac, celecoxib, fenoprofen, ibuprofen, naproxen, tolmetin, niflumic acid, and piroxicam.Citation7,8,13–22 Usually, the reported cases have been observed with prolonged use of these drugs—even topically—but they have also been reported shortly after initial intake.Citation2,14,15,18,21,23–25 The average exposure time in most cases has been 5.4 months.Citation18 Clinically, it presents as NS with AKI, microscopic hematuria, leukocyturia, pyuria, leukocyte cylindruria, and, rarely, other signs of hypersensitivity or eosinophilia are observed.Citation12 Renal biopsies commonly show glomerular lesions of minimal change disease or membranous glomerulopathy, and, less frequently, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.Citation3,13,15–17,23,24 The presence of NS associated with acute tubular necrosis without AIN—as shown in the case previously described—is extremely rare.Citation7,26

The mechanism of AIN is presumed to be mediated by delayed-type hypersensitivity.Citation23,25 NS after NSAIDs use is thought to be caused by the shift of arachidonic acid route of conversion by cyclooxygenase toward lipoxygenase, resulting in augmented production of leukotrienes that would lead to the activation of T helper lymphocytes.Citation27 These lymphocytes would affect podocytes, altering glomerular permeability and, therefore, causing nephrotic proteinuria.Citation10 It has also been claimed that the damage may be produced by the release of lymphokines from activated T cells.Citation27

Usually, prognosis in these cases is favorable after withdrawal of NSAIDs, with full renal function recovery and complete remission of NS.Citation7,12,18,21,25,28 When proteinuria persists for more than 1 month or renal failure lasts for more than 1–2 weeks after discontinuation of the drug, the use of steroids in high doses has been recommended, although there is no definitive evidence supporting it.Citation13,18 Few cases are reported in which NS has lasted for longer periods—up to 1 year—or renal function has been never recovered.Citation7,13–15,18,23,24 Renal replacement therapies have been rarely needed.Citation25

The only case reported in literature of NS from MLX use was observed on a 60-year-old man who received this drug over a few days for hip arthrosis. He was admitted due to clinical findings compatible with NS, and a renal biopsy showed minimal change nephropathy. Patient’s condition resolved quickly with the discontinuation of the drug. In his clinical evaluation, a history of two previous episodes of NS was noted after diclofenac intake, which led clinicians to conclude that he presented hypersensitivity to both drugs. After complete remission from NS, he received celecoxib during a month without presenting any symptoms or renal impairment.Citation9

Our patient also presented with NS a few days after MLX intake, probably due to podocyte damage as seen in her renal biopsy. However, unlike the case previously reported in literature, renal failure was caused by coexisting acute tubular necrosis. This complication was completely resolved after 35 days of treatment, but NS persisted with clinically relevant relapses that were definitively remitted after 4 years of treatment.

Although the possibility that this patient could have suffered from an idiopathic minimal change disease not associated with the use of NSAIDs can be raised, the intake temporality, the age of appearance, and the simultaneous coexistence with acute tubular necrosis make it highly likely that MLX was the causing factor.

The aim of communicating this case is to raise a warning about renal side effects of MLX and the need to quickly suspend them when faced with recent onset proteinuria.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- Galesić K, Morović-Vergles J, Jelaković B. Nonsteroidal antirheumatics and the kidney. Reumatizam. 2005;52:61–66.

- O´Callaghan CA, Andrews PA, Ogg CS. Renal disease and use of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ. 1994;308:110–111.

- Zadrazil J. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the kidney. Vnitr Lek. 2006;52:686–690.

- Whelton A. Clinical implications of nonopioid analgesia for relief of mild-to-moderate pain in patients with or at risk for cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(9A):3–9.

- Wen SF. Nephrotoxicities of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Formos Med Assoc. 1997;96:157–171.

- González E, Gutiérrez E, Galeano C, . Grupo Madrileño De Nefritis Intersticiales. Early steroid treatment improves the recovery of renal function in patients with drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2008;73:940–946.

- Almansori M, Kovithavongs T, Qarni MU. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor-associated minimal-change disease. Clin Nephrol. 2006;63:381–384.

- Alper AB Jr., Meleg-Smith S, Krane NK. Nephrotic syndrome and interstitial nephritis associated with celecoxib. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:1086–1090.

- Mihovilovic K, Ljubanovic D, Knotek M. Safe administration of celecoxib to a patient with repeated episodes of nephrotic syndrome induced by NSAIDs. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31: 351–355.

- Whelton A. Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Physiologic foundations and clinical implications. Am J Med. 1999;106:13S–24S.

- Ejaz P, Bhojani K, Joshi VR. NSAIDs and kidney. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:632–640.

- Deray G, Baumelou A, Beaufils H, Jacobs C. Drug-induced interstitial nephropathy with nephrotic syndrome. Presse Med. 1990;19:1985–1988.

- Huang JB, Yang WC, Yang AH, Lee PC, Lin CC. Arterial thrombosis due to minimal change glomerulopathy secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:358–361.

- Révai T, Harmos G. Nephrotic syndrome and acute interstitial nephritis associated with the use of diclofenac. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1999;111:523–524.

- Andrews PA, Sampson SA. Topical non-steroidal drugs are systemically absorbed and may cause renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:187–189.

- Radford MG Jr., Holley KE, Grande JP, . Reversible membranous nephropathy associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Am Med Assoc. 1996;276:466–469.

- Lanz B, Cochat P, Bouchet JL, Fischbach M. Short-term niflumic-acid-induced acute renal failure in children. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9:1234–1239.

- Chen YH, Tarng DC. Profound urinary protein loss and acute renal failure caused by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Chin J Physiol. 2011;54:264–268.

- Sirvent AE, Enríquez R, Amorós F, Reyes A. Nephrotic syndrome associated to celecoxib. Nefrologia. 2005;25:81–82.

- Inoue M, Akimoto T, Saito O, Ando Y, Muto S, Kusano E. Successful relatively low-dose corticosteroid therapy for diclofenac-induced acute interstitial nephritis with severe renal failure. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2008;12:296–299.

- Porile JL, Bakris GL, Garella S. Acute interstitial nephritis with glomerulopathy due to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents: A review of its clinical spectrum and effects of steroid therapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:468–475.

- Artinano M, Etheridge WB, Stroehlein KB, Barcenas CG. Progression of minimal-change glomerulopathy to focal glomerulosclerosis in a patient with fenoprofen nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 1986;6:353–357.

- Kleinknecht D. Interstitial nephritis, the nephrotic syndrome, and chronic renal failure secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Semin Nephrol. 1995;15:228–235.

- Grcevska L, Polenaković M, Ferluga D, Vizjak A, Stavrić G. Membranous nephropathy with severe tubulointerstitial and vascular changes in a patient with psoriatic arthritis treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Nephrol. 1993;39:250–253.

- Murray MD, Brater DC. Renal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33: 435–465.

- Sekhon I, Munjal S, Croker B, Johnson RJ, Ejaz AA. Glomerular tip lesion associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:e55–e58.

- Cunard R, Kelly CJ. T cells and minimal change disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1409–1411.

- Ohno I. Drug induced nephrotic syndrome. Nippon Rinsho. 2004;62:1919–1924.