Abstract

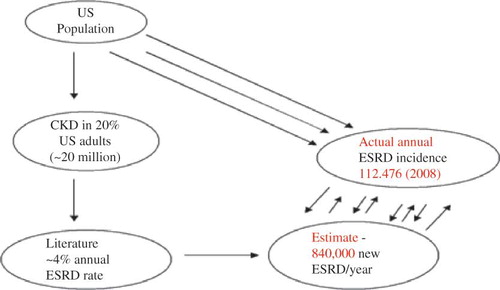

The just released (August 2012) US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) report on chronic kidney disease (CKD) screening concluded that we know surprisingly little about whether screening adults with no signs or symptoms of CKD will improve health outcomes and that clinicians and patients deserve better information on CKD. The implications of the recently introduced CKD staging paradigm versus long-term renal outcomes remain uncertain. Furthermore, the natural history of CKD remains unclear. We completed a comparison of US population-wide CKD to projected annual incidence of end stage renal disease (ESRD) for 2008 based on current evidence in the literature . Projections for new ESRD resulted in an estimated 840,000 new ESRD cases in 2008, whereas the actual reported new ESRD incidence in 2008, according to the 2010 USRDS Annual Data Report, was in fact only 112,476, a gross overestimation by about 650%. We conclude that we as nephrologists in particular, and physicians in general, still do not understand the true natural history of CKD. We further discussed the limitations of current National Kidney Foundation Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) CKD staging paradigms. Moreover, we have raised questions regarding the CKD patients who need to be seen by nephrologists, and have further highlighted the limitations and intricacies of the individual patient prognostication among CKD populations when followed overtime, and the implications of these in relation to future planning of CKD care in general. Finally, the clear heterogeneity of the so-called CKD patient is brought into prominence as we review the very misleading concept of classifying and prognosticating all CKD patients as one homogenous patient population.

BACKGROUND

The just released (August 2012) US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) report on chronic kidney disease (CKD) screening concluded that we know surprisingly little about whether screening adults with no signs or symptoms of CKD will improve health outcomes and that clinicians and patients deserve better information on CKD.Citation1 In 2002, the National Kidney Foundation Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) Clinical Practice Guidelines for CKD introduced the concept of CKD staging 1 – 5.Citation2 The implications of the NKF KDOQI CKD staging paradigms versus long-term renal outcomes remain uncertain and controversial.Citation3 In a 2009 review of this topic, Levey et al. asked the rhetorical question—“Do all patients with CKD need to be referred to a nephrologist?”Citation3 It is clear that still, nobody is sure of the correct answer to this rhetorical question, in 2012. Furthermore, even though the NKF CKD staging model assumes a translation of predictable real-time and time-dependent evolution of CKD through stages 1,2,3,4, and 5, the weight of available evidence points to the contrary.Citation3,4 Indeed, the natural history of CKD remains unclear with regard to factors that determine progression and non-progression of CKD, and we still have incomplete knowledge of the immediate, short-term, and long-term impacts of acute kidney injury (AKI) on CKD outcomes.Citation4–6 Moreover, there remains significant uncertainty and controversy regarding the vexed question of the simultaneously annualized ESRD rates versus death rates among CKD patients.Citation4–6

Keith et al. in 2004 reported an ESRD rate of 20% versus a death rate of 50% after 5 years among a CKD cohort of 27,998 patients in a managed care organization, whereas Menon et al. in 2008 demonstrated a higher ESRD rate of 60% versus a much lower death rate of 15% after 88 months in 1666 patients in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease studyCitation5,6 (). Alternatively, our 2009 single-center Mayo Clinic study revealed an ESRD rate of 18% versus a death rate of 13% after 4 years among a 100-CKD patient cohortCitation4 (). Heretofore, in this analysis, we have computed annual US ESRD incidence estimates, based on these three cited literature sources, and then compared these projections to actual reported US ESRD incidence for 2008 as published in the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) 2010 report for the year ending December 2008.Citation7

Table 1. Variability of reported annualized ESRD and annualized death rates among CKD populations from three studies, 2004–2009.

METHOD/RESULTS

We carried out a snap shot cross-sectional US CKD population analysis of projected annualized ESRD incidence based on the weighted rates from the three previously cited sources.Citation4–6 We then compared these estimates with actual US ESRD incidence for 2008 as reported in USRDS 2010 report.Citation7

A 2007 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report indicated that 16.5% of the US population who were 20 years of age and older had CKD with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 BSA, thus affecting about 20 million adult Americans.Citation8 We used this US CDC CKD population data as the base population for the annual ESRD incidence projections for 2008. The above three cited studies give a weighted average annualized ESRD rate of ∼4.2%.Citation4–6 This weighted average annualized ESRD rate of 4.2%, when applied to the 16.55% of the US CKD population for 2007 translated to a projected 840,000 new ESRD cases for 2008. However, to the contrary, according to the USRDS 2010 Annual Data Report, the actual number of new ESRD patients (annual incidence) in the US for 2008 was 112,476 (). Therefore based on available literature, ESRD rate projections exceeded the actual annual ESRD incidence numbers by about 650% (). Similar discrepancies in projected versus actual numbers apply to death rate estimates among US CKD patients.

DISCUSSION

From the foregoing, we therefore conclude that we as nephrologists in particular, and physicians in general, still do not understand the true natural history of CKD. Current consensus that “most CKD patients all die of cardiovascular events before reaching ESRD” is simply a myth, is unfounded, is unproven, and is untrue. Current literature studies and reports of ESRD rates and death rates among CKD patients very clearly and excessively overestimate these ratios, sometimes in excess of a whopping 1000%, in some instances. Such huge dilemma and misleading statistics are untenable and unacceptable.

Besides, the NKF KDOQI CKD conceptual model introduced in 2002 must be re-evaluated. The correct answer to the rhetorical question again “Do all patients with CKD need to be referred to a nephrologist?” remains uncertain but anecdotal evidence points to the contrary.Citation3,9 Also, the implications of the so-called pre-dialysis care of CKD patients is another huge fall out of the new NKF CKD staging paradigm.Citation9 The unintended consequences of the increasing calls for “CKD” patients to see physicians who are nephrology specialists potentially could lead to a ballooning of Nephrology CKD visits, adding to the already escalating unsustainable US healthcare costs.Citation10–12 It remains conjectural at this point whether, in fact, such frequent visits by all “CKD” patients to nephrologists indeed translate to better patient outcomes.Citation9 We doubt it. It is not known whether some classification of CKD with deference to patient age may help resolve these unanswered questions.Citation9

Besides, it would appear that some CKD patients simply remain stable and do not progress, whereas other CKD patients appear more susceptible to progression of renal disease to ESRD.Citation3 In a 2011 Canadian report, Sikaneta et al. demonstrated the longitudinal changes of eGFR and CKD stages during a 1.1-year observation period among 1262 patients, mean age 71.25 years, retrospectively drawn from two large Canadian renal clinics.Citation13 The authors described CKD stage variability (defined by changes in CKD stages) and reported that CKD stage changed in 40% of the cohort (including 7.4% in whom CKD stage improved), whereas CKD stage remained static in 762 (60.4%) patients.Citation13 Even important was the potential negative impact of angiotensin inhibition in influencing the natural history of CKD.Citation13–15

In June 2011, we completed the analysis of trajectories of eGFR changes of all stage 4 CKD patients, with eGFR in the 15.0–29.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 BSA range, present in a Mayo Clinic electronic laboratory database, reported between 19 April 2009 and 19 April 2011.Citation16 All CKD patients who had received renal replacement therapy (RRT) for AKI or ESRD were excluded from the analysis. We included for analysis, all CKD patients with at least three recorded eGFR values and with a minimum of 6 months between the first and the last reported eGFR estimations.Citation16 After excluding 62 ESRD patients, and all who received RRT for AKI, 241 patients qualified for this analysis.Citation16 There were 102 males and 139 females. In over 95% of the CKD patients, eGFR remained very stable and did not vary by as much as 5 eGFR points (<25% from baseline) over the 2-year study period.Citation16 We concluded from this cross-sectional study that eGFR in the majority of CKD stage 4 patients remained stable even after 2 years of follow up and we speculated that current CKD staging paradigms, as envisaged by the NKDOQI guidelines, implying a steady-state, time-dependent, and progressive decline of eGFR overtime was only speculative, unproven ,and possibly flawed.Citation16 The various reported formulas attempting to estimate CKD progression by assuming a steady state decline in eGFR in mL/min/year, in our opinion, are likely to be misguided.Citation16 We opined that further studies were warranted to properly inform and educate both the medical profession and the general population on these very critical knowledge deficiencies regarding CKD outcomes.Citation1,16

From the foregoing, we have therefore surmised that a new concept of “asymptomatic CKD” versus “symptomatic CKD” must be entertained and re-examined in light of new and accruing evidence in the literature and it would appear that some patients with CKD (eGFR <60) simply remain stable and are non-progressors, whereas others are progressors and progress to ESRD much faster overtime.Citation16 Determining such predisposing factors or determinants of CKD progression will have huge clinical implications towards the improvement of CKD care not just in the US, but worldwide.

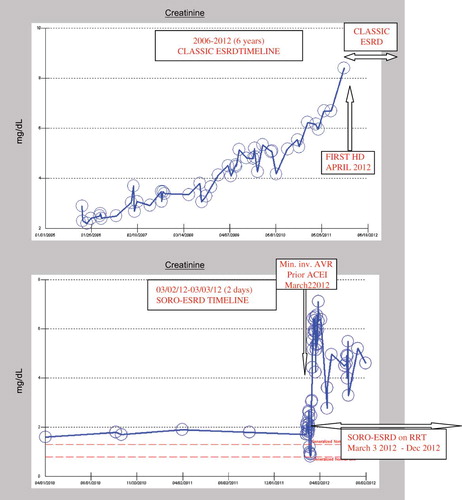

Additionally, the current knowledge of the effects and impact of AKI episodes on CKD progression and renal outcomes is incomplete. Okusa et al., in a 2009 editorial published in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, writing on behalf of the Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology analyzed the impact of AKI on CKD-ESRD progression.Citation17 The conclusion of this AKI Advisory Group was that new data suggest that a strikingly large percentage of patients who have AKI require permanent RRT or do not fully recover renal function, and that this population has an important and growing impact on the global epidemiology of CKD and ESRD.Citation17 Incidentally, we first described in 2010, the previously unrecognized new syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease (SORO-ESRD) in the journal Renal Failure.Citation18–21 This is the sudden, precipitate, unanticipated and rapidly irreversible ESRD occurring in CKD patients following on the heels of AKI episodes.Citation18–21 This is veritably distinct from the classic view of CKD-ESRD progression as characterized by a predictable, linear, smooth and continuous progressive, and time-dependent relentless decline in renal function in CKD patients, with predictably increasing serum creatinine, leading inexorably to ESRD and RRT.Citation22–26 In , we show representative serum creatinine trajectories in two patients: one who developed ESRD in the classic manner (top) and one who developed SORO-ESRD rather abruptly (bottom) (). The former is a 71-year-old hypertensive diabetic CKD woman who progressively over the last 6 years, 2006–2012, developed worsening renal failure, inexorably ending up to require hemodialysis in April 2012 (top). The latter was a 74-year-old Caucasian hypertensive diabetic CKD male patient who developed accelerated renal failure consistent with SORO-ESRD in March 2012 immediately following minimally invasive aortic valve replacement while concurrently on Lisinopril 40 mg/day. He remains on in-center maintenance hemodialysis in December 2012 with a baseline serum creatinine of 5 mg/dL ( bottom).

Figure 2. Composite figure of serum creatinine trajectories for a CKD patient exhibiting the classic CKD-ESRD progression (top) and a CKD patient exhibiting the features of SORO-ESRD (bottom).

Also, earlier in the journal Quarterly Journal of Medicine in 2009, we had espoused on the concept of renoprevention as a means of attenuating and limiting the incidence of AKI in our CKD patients.Citation27 In a recent coronary care unit (CCU) hypothetical CKD patient outcome model analysis, published in the journal Renal Failure, we had shown both improved renal outcomes and huge cost savings through the application of simple and common sense renoprevention strategies.Citation28 Indeed, a more forceful and pragmatic application of renoprevention strategies in the CCU—pre-emptive withholding of nephrotoxics including RAAS blockers, aggressive prevention of peri-operative hypotension, avoiding nephrotoxic exposure to compounds such as contrast dyes and antibiotics would lead to less AKI, potentially less SORO-ESRD, and therefore better patient and renal outcomes, as well as massive dollar savings.Citation27,28

Finally, it is our hope that our newly designed CKD Express © IT-Software, a stand-alone IT software program that is designed to facilitate remote care of CKD patients through linkages to chemistry laboratory data bases, a program that is currently in US patent application, would help bridge these yawning gaps in our knowledge of the natural history of CKD and will hugely impact the development of more effective, efficient, and cost-saving new models of pre-dialysis CKD care.Citation29

We would not end this treatise without addressing the basic assumption that CKD, by itself, is or represents a singular disease entity.Citation30,31 Bansal and Hsu, in a 2008 analysis of the long-term outcomes of patients with chronic kidney disease, echoed the observation that the disparate ESRD and mortality rates in various CKD populations as reported by various studies in the literature only emphasized the heterogeneity of CKD populations.Citation30 The results of their analysis emphasized the heterogeneity of the CKD population. Nephrologists should not rely on CKD staging alone to direct management of risk-stratify patients with CKD, but should also consider the etiology, rate of progression of kidney disease, patient age, and cardiovascular disease risk factors.Citation30 Clearly, diabetic CKD, which includes diabetic CKD with proteinuria versus diabetic CKD without proteinuria, diabetic CKD with nephrotic range proteinuria versus diabetic CKD without microalbuminuria, CKD from adult polycystic kidney disease, CKD from chronic glomerulonephritis, hypertensive CKD with and without proteinuria, all respectively reflect and represent very different disease entities and should be expected to potentially behave differently.Citation30–32 Even CKD patients with established diabetic nephropathy can overtime exhibit very differential and different profiles in terms of CKD progression.Citation31 Tsalamandris et al., in 1994, reported that of 40 patients with diabetes, 15 developed progressive increases in albumin excretion rate with no decline in GFR, 13 had progressive increases in albumin excretion rates with decreasing GFR, whereas 12 (8 with type 2 diabetes) had decreasing GFR values without significant increase in albumin excretion rates.Citation31 Thrown into this case-mix of the CKD syndrome is the unanticipated, unplanned, and potentially huge impacts of AKI episodes on CKD progression as classically typified by the SORO-ESRD.Citation17–21

Finally, we conclude that current CKD staging paradigms are at best untested and unproven and that available literature on CKD outcomes regarding ESRD rates and death rates are confusing, conflicted, and grossly overestimate the actual numbers experienced here in the USA. The need to individualize CKD care cannot be overemphasized as CKD represents a whole wide spectrum of distinctly different clinical disease entities. As a result of the above limitations in our knowledge base of CKD, current CKD-ESRD planning paradigms will likely be unsuccessful and sometimes futile. Furthermore, the potential impact of AKI on the ESRD epidemic by causing SORO-ESRD calls for more urgent research efforts. Moreover, an increasing role for preventative nephrology to limit AKI in medical practice demands a lot more attention than it is getting presently. Finally, we will once again re-echo the sentiments of the 2012 USPSTF report on CKD screening that concluded that we know surprisingly little about whether screening adults with no signs or symptoms of CKD will improve health outcomes and that clinicians and patients deserved better information on CKD.Citation1

Declaration of interest

No conflicts of interest declared.

REFERENCES

- Moyer VA. On behalf of the US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chronic kidney disease: US Preventive Services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. August 28, 2012. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00533 [Epub ahead of print].

- National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(Suppl. 1):S1–S266.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Coresh J. Conceptual model of CKD: applications and implications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(3 Suppl. 3):S4–S16.

- Onuigbo MA. The natural history of chronic kidney disease revisited – a 72-month Mayo Health System Hypertension Clinic practice-based research network prospective report on end-stage renal disease and death rates in 100 high-risk chronic kidney disease patients: a call for circumspection. Adv Perit Dial. 2009;25:85–88.

- Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH. Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:659–663.

- Menon V, Wang X, Sarnak MJ, . Long-term outcomes in nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1310–1315.

- US Renal Data System. USRDS 2010 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2010. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/2010/ADR_booklet_2010_lowres.pdf, http://www.usrds.org/2009/pdf/V2_02_INC_PREV_09.PDF. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors – United States, 1999–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:161–165.

- Onuigbo M, Onuigbo N. Predialysis nephrology care of older patients approaching end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2066.

- The Concord Coalition. Escalating Health Care Costs and the Federal Budget, April 2, 2009. Available at: http://www.concordcoalition.org/files/uploaded_for_nodes/docs/Iowa_Handout_final.pdf.Accessed September 12, 2011.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Snapshots: Health Care Spending in the United States and Selected OECD Countries, April 2011. Available at: http://www.kff.org/insurance/snapshot/OECD042111.cfm.Accessed September 12, 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditure Projections 2010–2020. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/proj2010.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2011.

- Sikaneta T, Abdolell M, Taskapan H, . Variability in CKD stage in outpatients followed in two large renal clinics. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011. doi:10.1007/s11255-011-9934-9.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo NT. Variability in CKD stage in outpatients followed in two large renal clinics: Implications for CKD trials and the status of current knowledge of patterns of CKD to ESRD progression. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44(5);1589–1590 [Epub 2011 Aug 30].

- Sikaneta T, Roscoe J, Fung J, . Variability in CKD stage in outpatients followed in two large renal clinics: Implications for CKD trials and the status of current knowledge of patterns of CKD to ESRD progression: response to Dr. Onuigbo. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44(5);1591–1592 [Epub 2011 Oct 14].

- Onuigbo MA. The validity of current CKD staging paradigms revisited and disputed: a 2-year snap shot of stage IV CKD patients in a Mayo Clinic laboratory database: a call for process reengineering in nephrology practice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:686A (SA-PO2472) (Abstract).

- Okusa MD, Chertow GM, Portilla D; Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology. The nexus of acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, and World Kidney Day 2009. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(3):520–522 [Epub 2009 Feb 18].

- Onuigbo MA. Syndrome of rapid-onset end-stage renal disease: A new unrecognized pattern of CKD progression to ESRD. Ren Fail. 2010;32(8):954–958.

- Onuigbo MAC, Onuigbo N. Syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease revisited – Observations from two chronic kidney disease populations in two continents. US Nephrology. 2010;5(2):81–85.

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo N. Chronic Kidney Disease and RAAS Blockade: A New View of Renoprotection. London: Lambert Academic Publishing GmbH 11 & Co. KG; 2011.

- Onuigbo MAC, Onuigbo NTC. The syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease (SOROESRD) – a new Mayo Clinic dialysis services experience, January 2010–February 2011. In: Di Iorio B, Heidland A, Onuigbo M, Ronco C, eds. Hemodialysis: How, When and Why. New York: NOVA Publishers; 2012:443–485.

- The GISEN Group. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia). Lancet. 1997;349:1857–1863.

- O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, . Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2758–2765.

- Chiu YL, Chien KL, Lin SL, Chen YM, Tsai TJ, Wu KD. Outcomes of stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease before end-stage renal disease at a single center in Taiwan. Nephron Clin Pract. 2008;109:c109–c118.

- Yoshida T, Takei T, Shirota S, . Risk factors for progression in patients with early-stage chronic kidney disease in the Japanese population. Intern Med. 2008;47:1859–1864.

- Conway B, Webster A, Ramsay G, . Predicting mortality and uptake of renal replacement therapy in patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1930–1937.

- Onuigbo MAC. Reno-prevention vs. reno-protection: a critical re-appraisal of the evidence-base from the large RAAS blockade trials after ONTARGET – a call for more circumspection. QJM. 2009;102:155–167 [Epub ahead of print January 5 2009].

- Onuigbo M. Renoprevention: a new concept for re-engineering nephrology care: an economic impact and patient outcome analysis of two hypothetical patient management paradigms in the CCU. Ren Fail. 2013;35(1):23–28.

- Onuigbo MAC. CKD express © – a new IT-software proposed for a paradigm change in CKD care. Open Med Inform J. 2012;6:26–27.

- Bansal N, Hsu CY. Long-term outcomes of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4:532–533.

- Tsalamandris C, Allen TJ, Gilbert RE, . Progressive decline in renal function in diabetic patients with and without albuminuria. Diabetes. 1994;43:649–655.

- Onuigbo MA. Causes of renal failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:1855.