Abstract

Rhabdomyolysis ranges from an asymptomatic illness with elevated creatine kinase levels to a life-threatening condition associated with extreme elevations in creatine kinase, electrolyte imbalances, acute renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The most common causes are crush injury, overexertion, alcohol abuse, certain medicines, and toxic substances. A number of electrolyte abnormalities and endocrinopathies, including hypothyroidism, thyrotoxicosis, diabetic ketoacidosis, nonketotic hyperosmolar state, and hyperaldosteronism, cause rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure are unusual manifestations of pheochromocytoma. There are a few case reports with pheochromocytoma presenting rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure. Herein, we report a case with pheochromocytoma crisis presenting with rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure.

Introduction

Rhabdomyolysis is a potentially life-threatening condition caused by a breakdown of skeletal muscle and the release of the intracellular contents into the circulatory system.Citation1 There are many possible causes, including crush injury, excessive muscular activity, medications, infections, alcohol abuse, and varied metabolic, connective tissue, rheumatologic, and endocrine disorders.Citation2 An elevated plasma creatine kinase (CK) level is the most sensitive laboratory finding pertaining to muscle injury; major life-threatening complications include hyperkalemia, acute renal failure, and compartment syndrome.Citation3 Patients can usually recover completely from rhabdomyolysis if the syndrome is recognized and treated promptly, thereby preventing late complications. Severe electrolyte imbalances, including hypernatremia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia, may lead to rhabdomyolysis. Endocrine abnormalities such as hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), and hyperaldosteronism have been reported to cause rhabdomyolysis.Citation1–3

Pheochromocytomas are rare, catecholamine-secreting tumors that represent a potentially curable form of endocrine hypertension. The prevalence of pheochromocytoma in hypertensive patients is 0.1–0.2%.Citation4 More than 90% of the incidences of pheochromocytoma occur intra-abdominally, most frequently in the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla. Approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas are hereditary.Citation5 The most prevalent clinical presentation is hypertension, headaches, excessive sweating, pallor, and palpitations. Less common symptoms include nausea, fever, anxiety, abdominal pain, or deterioration of the blood glucose.Citation4,Citation5 Spontaneous rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure are rare complications of pheochromocytomas.6–8 Pheochromocytoma crisis is a rare life-threatening endocrine emergency with a reported mortality as high as 85%. Acute and rapidly progressive hemodynamic disturbances result from the actions of high quantities of catecholamines secreted by the tumor and lead to multiorgan failure.9

Herein, we report a case with pheochromocytoma crisis presenting with rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure.

Case report

A 41-year-old woman presented at an outside hospital with severe myalgia, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and confusion, which she had experienced for 2 days. She subsequently was transferred to the Emergency Center at Trakya University’s School of Medicine. She had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (HT) one year earlier. The patient had been receiving pioglitazone (30 mg/day), candesartan-hydrochlorothiazide (16–12.5 mg/day) therapies for DM and HT. Her history included cigarette smoking for 20 years.

Upon physical examination, she was found to have a body temperature of 38.5 °C, a blood pressure of 150/100 mmHg despite antihypertensive therapy, and a heart rate of 96 BPM. She appeared seriously ill. Pulmonary congestion was present and a chest X-ray revealed bilateral pleural effusion, particularly on the left side. An electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm and non-diagnostic T-wave changes. The echocardiogram demonstrated left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and 60% ejection fraction.

The laboratory results upon admission are detailed in . The patient’s blood glucose, urea, and creatinine levels were all elevated. Her serum levels were 5.3 mmol/L for potassium, 8.4 mg/dL for phosphorus, 5055 IU/L for CK, 965 IU/L for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and 8.3% for HbA1c. Thyroid function tests showed euthyroid sick syndrome with low T3 and TSH levels. Dipstick urinalysis demonstrated 1–2 leukocytes, 20 erythrocytes with 1.010 density. Based on these results, she was transported to our intensive care unit with an admitting diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure. There was no history of crush injury, increased physical exercise, seizures, recent viral illness, alcohol and drug abuse, or musculoskeletal disease, which can cause rhabdomyolysis.

Table 1. The laboratory results of the patient on the admission and follow-up.

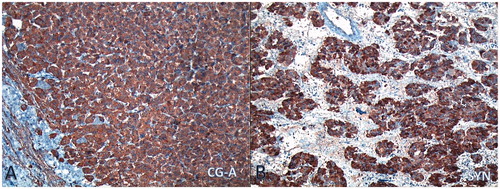

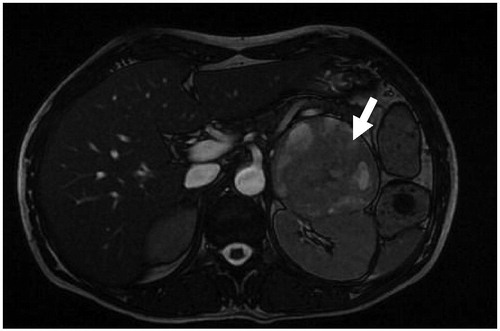

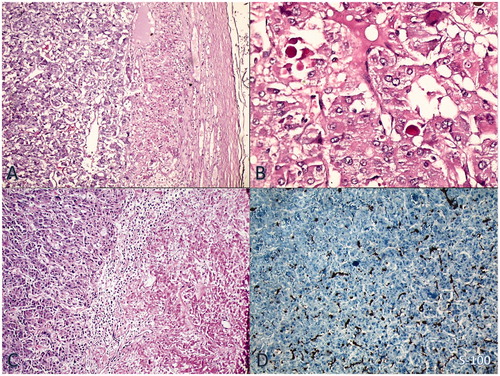

Following oxygenation, intravenous saline, diuretic, and nitroglycerin were infused until blood pressure stabilized. Episodic severe hypertension was observed with blood pressure reaching as high as 230/150 mmHg, alternating with orthostatic hypotension. Oxygenation improved without intubation. She was treated with intravenous insulin for blood glucose regulation. Ampicillin-sulbactam (1 gr–500 mg, tid) and clindamycin (600 mg, tid) were given to the patient for 14 days. Blood and urine culture samples were obtained before antibiotherapy, but all were negative during this period. Hemodialysis was begun on the second day of hospitalization. Creatinine clearance was obtained at 14 mL/min, with proteinuria (978 mg/day). Hemodialysis was continued for 3 days. The patient had marked symptomatic improvement and she became polyuric. Serum urea, creatinine, phosphorus, and CK levels decreased slowly (). Abdominal ultrasonography showed normal kidney size and echogenicity with left adrenal mass. She was transported to the endocrinology in-patient clinic for further diagnostic tests. Abdominal MRI revealed a 9 × 6 cm-sized left adrenal mass. It was hyperintense on the T2-weighted image and had necrotic areas (). Because urinary fractionated metanephrine was higher at 642 µg/day (normal range: 0–350 µg/day), she was diagnosed with pheochromocytoma. After oral administration of the alpha-blocker agent (increasing doses, doxazosin 8 mg/day), atenolol (50 mg/day) and amlodipine (10 mg/day), respectively, were added. She underwent surgical resection of the tumor after two weeks. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Immunohistochemical studies were positive for Ki-67 at less than 1%. Chromogranin positivity with heterogeneous reaction, strong positivity with synaptophysin, and S100 positivity were determined ( and ). One week after the operation, urinary metanephrine levels returned to normal and she did not need any antihypertensive or anti-diabetic drugs. The patient was subsequently discharged and has remained stable at home.

Figure 1. MRI showed a 9 × 6 cm-sized left adrenal mass, and the mass had hyperintense on T2- weighted image with necrotic areas (arrow).

Figure 2. (A) Notice on the left side of the figure typical nested pattern of the tumor resembling normal adrenal medulla (H&E × 50). (B) High power view shows tumor cells with intracytoplasmic eosinophilic globules (H&E × 200). (C) Right-sided coagulative necrosis of the tumor (H&E × 50). (D) Sustentacular cells immunostained for S100 protein at the periphery of the tumor nests (IHC × 50).

Discussion

Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure have been reported as a consequence of a wide spectrum of clinical conditions, including crush injuries, seizures delirium, hyperthermia, viral infections, excessive ethanol or narcotic ingestion, various drugs, electrolyte imbalances, and endocrine disorders.Citation10 Intracellular substances involve potassium; phosphate; the enzymes CK, LDH, aldolase; and the muscle protein myoglobin being released into the extracellular space.Citation6 The CK characteristically increases more than five times the upper normal limit. Although we could not measure serum aldolase levels, elevation in plasma aminotransferases, CK, and LDH levels accompanied by high serum phosphorus levels with severe myalgia suggested rhabdomyolysis in this patient. The peak CK level is seen 12–24 hours upon the onset of rhabdomyolysis; therefore, the value at the time of admission represented an already declining one. If the patient had been referred to our hospital earlier, we could have detected myoglobinuria by use of a dipstick, as well as higher levels of CK. There was no history of causative factors which can result in rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis is an unusual manifestation of pheochromocytoma.Citation6–8 In our patient, massive catecholamine release manifested itself as a hypertensive crisis, producing severe vasoconstriction and thereby triggering ischemia of muscle tissue. We believe that this patient’s pheochromocytoma crisis was primarily responsible for the development of rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure.

Pheochromocytomas can present with various life-threatening cardiovascular symptoms, such as hypertensive crisis, shock or profound hypotension, acute heart failure, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and cardiomyopathy. Pheochromocytoma can occur as an emergency with multisystem failure and pulmonary, neurologic, and renal emergencies.Citation9 The clinical presentation can be mistaken for septicemia, in which case appropriate treatment is delayed. Fever and acute inflammatory symptoms may be due to interleukin-6 production by the tumor, similar to findings in our patient.Citation11

There have also been a few case reports linking acute renal failure to pheochromocytoma.Citation6–8 Many of the patients involved had evidence of muscle damage with elevated CK levels, but elevated urinary myoglobin levels were not confirmed in any of the cases. We could not detect a urinary myoglobin level in this patient. Shemin et al. reported a 29-year-old woman who presented with the sudden onset of rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuric renal failure and was diagnosed with pheochromocytoma.Citation6 Oristrell-Salva,Citation7 in a brief unreviewed report, described a patient with pheochromocytoma presenting with renal failure, pulmonary edema, and dark red urine accompanied by a CK level of 30,000 IU/L. Raman et al. reported a patient with pheochromocytoma presenting with cardiogenic shock and acute renal failure.Citation8

In pheochromocytoma, the release of large amounts of catecholamines can precipitate ischemia and necrosis in skeletal muscle through the vasoconstriction. Catecholamine-induced volume contraction is one of the possible mechanisms.Citation12 Pheochromocytoma can cause muscle damage; there is evidence in the literature of histologically proven focal myositis with degeneration of skeletal muscle fibers, increased sarcolemmal nuclei, and giant cells in a patient with a large pheochromocytoma at autopsy.Citation13

Making a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma depends on demonstrating excessive production of catecholamines (total and fractionated metanephrines, vanillylmandelic acid) with tumor localization. Although recent studies suggest that measurement of plasma free metanephrines is a superior test for confirming the diagnosis, a high urinary fractionated metanephrine level was detected at our hospital. We could not measure plasma-free metanephrine and normetanephrine levels. This is a limiting factor in this report. Conventional imaging methods that have been used in the preoperative evaluation of patients with a biochemically confirmed pheochromocytoma include computed tomography (CT), MRI, and 131Imeta-iodobenzylguanidine scan.Citation4 Pheochromocytoma masses appear characteristically bright, with a high signal on T2-weighted images and no signal loss on T1-weighted opposed-phase images, which is similar to what we saw in our patient.

Surgical resection is the definitive treatment for patients with pheochromocytoma. The patient must be adequately prepared with alpha-adrenergic blockade and complete restoration of fluid and electrolyte balance.Citation14 Most cases of sporadic pheochromocytoma are unilateral; the treatment of choice for tumors less than 6 cm in size is a laparoscopic adrenalectomy. After blood pressure and electrolytes returned to normal, we performed an open adrenalectomy because of the large size of the mass.

In conclusion, pheochromocytoma crisis is a rare life-threatening endocrine emergency with high morbidity and mortality. Rhabdomyolysis ranges from an asymptomatic illness with elevation in the CK level to a life-threatening condition associated with extreme elevations in CK, electrolyte imbalances, acute renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Spontaneous rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure is a rare complication of pheochromocytoma. Early diagnosis and prompt management are crucial. Therefore, pheochromocytoma should be excluded in the differential diagnosis in patients with rhabdomyolysis.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Acknowledgments

Inform consent was obtained from the patient.

References

- Sauret JM, Maridines G, Wang GK. Rhabdomyolysis. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:907–912

- Huerta-Alardin AL, Varon J, Marik P. Bench-to-bedside review: rhabdomyolysis—an overview for clinicians. Crit Care. 2005;9:158–169

- Khan FY. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Neth J Med. 2009;67:272–283

- Mittendorf EA, Evans DB, Lee JE, Perrier ND. Pheochromocytoma: advances in genetics, diagnosis, localization, and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;21:509–525

- Bryant J, Farmer J, Kessler LJ, Townsend RR, Nathanson KL. Pheochromocytoma: the expanding genetic differential diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1196–1204

- Shemin D, Cohn PS, Zipin SB. Pheochromocytoma presenting as rhabdomyolysis and acute myoglobinuric renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:2384–2385

- Oristrell-Salva J, Mirada-Canals A. Phaeochromocytoma and rhabdomyolysis. Br Med J. 1984;288:1198

- Raman GV. Phaeochromocytoma presenting with cardiogenic shock and acute renal failure. J Hum Hypertens. 1987;1:237–238

- Brouwers FM, Eisenhofer G, Lenders JWM, Pacak K. Emergencies caused by pheochromocytoma, neuroblastoma, or ganglioneuroma. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2006;35:699–724

- Knochel JP. Rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria. Semin Nephrol. 1981;1:75–86

- Kang JM, Lee WJ, Kim WB, et al. Systemic inflammatory syndrome and hepatic inflammatory cell infiltration caused by an interleukin-6 producing pheochromocytoma. Endocr J. 2005;52:193–198

- Anafaroglu I, Ertorer E, Haydardedeoglu FE, Colakoglu T, Tokmak N, Demirag NG. Rhabdomyolysis and acute myoglobinuric renal failure in a patient with bilateral pheochromocytoma following open pyelolithotomy. South Med J. 2008;101:425–427

- Bhatnagar D, Carey P, Pollard A. Focal myositis and elevated creatine kinase levels in a patient with phaeochromocytoma. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:197–198

- Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4069–4079