Abstract

In recent years, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis has become the commonest cause of the nephrotic syndrome seen in adults. Secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is observed when glomerular workload is increased. We report a case of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with nephrotic syndrome secondary to high-altitude polycythemia (HAPC). Our case points out that for patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, who presented with nephrotic syndrome secondary to HAPC, treatments for HAPC are crucial for the reduction of proteinuria and renal protection instead of glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive drugs.

Introduction

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), categorized as primary and secondary by etiology classification,Citation1 is becoming the commonest cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults in recent years. Secondary FSGS can be observed in polycythemia.Citation2 Polycythemia is a kind of blood system disease characterized by abnormal proliferation in the erythroid series; it can be divided into congenital and acquired categories and causes an increase in blood viscosity and decrease in blood flow, which leads to hypoxia and accumulation of acid metabolites in multiple organs including heart, brain, and kidney. High-altitude polycythemia (HAPC) is one of the commonest causes of secondary polycythemia.Citation3 The number of case reports of glomerulonephritis developing secondary to polycythemia is limited; here we report a case of FSGS secondary to polycythemia caused by HAPC.

Case report

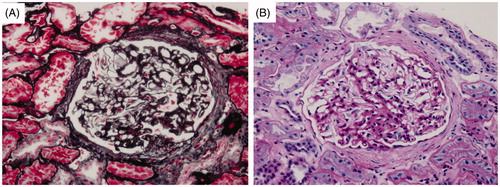

This patient was a 35-year-old Han Chinese male with a 3-year history of symmetric pitting edema of the lower limbs. He worked in Tibet as a driver during the past 10 years. The edema was aggravated while he was living on the plateau, and relived in the plain. When he presented to a local hospital 5 months ago, urine and serum tests showed that proteinuria 3+, 24-hour urine protein (24hHTP) 7.3 g, serum albumin (Alb) 26 g/L, and he was diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome. Although he had received prednisone at an initial dose of 60 mg/day, no significant improvement was observed, and the patient was thereafter admitted to our hospital. Physical examination on admission indicated that cyanotic lips and moderate pitting edema had occurred over both legs. His cardiac and pulmonary function appeared normal. Blood cell count and chemistry data upon admission are shown in . Urine analysis showed: proteinuria 3+, specific gravity 1.016, RBC 11/HP, WBC 11/HP, pus cell (–), granular casts (−). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti dsDNA antibody, complement, immunoglobulin, and other immunological examination were not presented abnormally. HBV markers were negative. Clotting diagram showed no abnormal findings. The blood rheology examination showed: low cut whole blood viscosity (11/s) 26.82 mpaċs (normal range 17.63–21.35 mpaċs), low cut whole blood viscosity (101/s) 9.70 mpaċs (normal range 6.19–7.88 mpaċs), medium cut whole blood viscosity (501/s) 6.05 mpaċs (normal range 4.27–5.45 mpaċs), high cut whole blood viscosity (2001/s) 5.07 mpaċs (normal range 3.53–4.65 mpaċs), whole blood low cut relative index 20.73 (normal range 10.62–16.94 mpaċs), whole blood high cut relative index 3.9 (normal range 2.13–3.69 mpaċs); plasma viscosity, whole blood reduction viscosity value (low cut), and whole blood reduction viscosity value (high cut) were normal. Blood gas analysis: pH 7.380, PCO2 43.0 mmHg, PaO2 97.0 mmHg, SaO2 97.0%, HCO3 25.4 mmol/L, BE −0.1 mmol/L. A bone marrow aspiration showed that granulocytic series accounted for 61%, erythrocytic series accounted for 26%; polychromatic normoblast and orthochromatic normoblast were primarily observed, with a ratio of 2.34:1. The patient was then diagnosed with polycythemia. A percutaneous renal needle biopsy was taken (). Six to seven glomeruli were found in the specimen for light microscopy. One of the glomeruli showed global sclerosis, and one adhered to Bowman’s capsule with early focal segmental sclerosis. The non-sclerotic glomeruli showed mild volume expansion and mesangial hypercellularity. Tubular epithelial cells exhibited moderate swelling, and interstitium and capillary appeared normal in thickness. The immunofluorescence findings were negative for IgA, IgG, IgM, C3, C4, C1q, fibrin, k and γ chains. The electron microscopic observation showed marked foot process fusions of the podocytes in microscopically segmental sclerosis and normal glomerulus, basement membrane uniformly thickened. These findings were consistent with FSGS.

Figure 1. Glomerulus image showing focal segmental sclerosis. (A) Periodic acid silver methenamine stain, ×400; (B) Periodic acid-Schiff stain, ×400.

Table 1. Results of laboratory tests during 20 days of disease course.

The patient was diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome (NS, pathologic type: FSGS) and HAPC. He then received anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel. Additionally, phlebotomy (300 mL, 300 mL, and 200 mL respectively) was administered three times. Eighteen days later, the patient’s edema was relieved completely, and the symptom of cyanotic lips markedly improved; his blood cell counts were reducing toward normal levels (Hb 150 g/L, HCT 47%) and 24hHTP decreased substantially (1.27 g/24 h). Results of laboratory tests during 20 days are shown in . On the 15th day after being discharged from our hospital, the patient responded with gradual improvement of his clinical manifestation, with a 24hHTP of 1.32 g/24 h and a urine analysis of proteinuria (2+).

Discussion

FSGS is a glomerular disease characterized by the presence of proteinuria and a high incidence of progression to renal insufficiency, and is categorized as primary and secondary by etiology classification.Citation4 The pathogenesis of secondary FSGS remains unclear but appears to be the result of glomerular hypertrophy and hyperfiltration developing as a response to decreased renal mass. Secondary causes also associated with FSGS are proliferative glomerulonephritis, SLE, vasculitis, infection with HIV, heroin abuse, and reflux nephropathy,Citation5 which lead to glomerular epithelial cell injury resulting in segmental glomerular scars involving some glomeruli.

Polycythemia may appear in the progresses of various renal diseases; however, the pathogenesis of FSGS secondary to polycythemia is unknown. It was believed that hyperviscosity, hypoperfusion, and platelet thrombus formation in polycythemia are highly risk factors of FSGS.Citation6 HAPC is one of the commonest causes of secondary polycythemia.

In hypoxia conditions (e.g., at high altitude), the proliferation of RBC can be upregulated through oxygen-sensing pathways,Citation7,Citation8 which therefore, causes polycythemia. For lower altitude dwelling population (e.g., Han Chinese population), the increase of hemoglobin as a response to hypoxia is more sensitive than people who live permanently at high altitude (e.g., Tibetan populations).Citation9 Tibetan populations may have genetic polymorphisms, which help to protect high altitude dwellers against the development of severe hemoglobin,Citation3 Han Chinese population do not have the same gene polymorphisms. According to the 2008 WHO guideline, the diagnosis of polycythemia should be considered when it meets one of followings: (1) Hb > 185 g/L in a male or 165 g/L in a female; (2) Hb > 170 g/L in a male or 150 g/L in a female, with a sustained Hb level over 20 g/L above baseline.Citation10 Combining medical history and laboratory examinations, the present patient who is a Han Chinese male having worked in Tibet for 10 years and has been diagnosed with HAPC.

Reports of glomerular injury secondary to hypoxemia polycythemia were rare.Citation11 In this case, the diagnosis of FSGS and polycythemia is confirmed by renal and bone marrow aspiration. There are three evidences that support our diagnosis from the view of clinical aspects. Firstly, as other secondary causes of FSGS could be excluded according to clinical evidence and laboratory examinations, we thought that the FSGS determined in this patient monitored due to polycythemia. Secondly, renal biopsy was taken and the immunofluorescence findings were negative, which implied other immune diseases could be excluded, so we thought that his kidney injury was most likely caused by HAPC. Thirdly, this patient had NS, but the glucocorticoid therapy is noneffective. However, clinic manifestation and proteinuria were gradually alleviated after moving to plain, phlebotomy therapy and anticoagulation therapy, which suggests a close association between NS/FSGS and HAPC.

Presently, the primary polycythemia therapies contain aspirin, hydroxyurea, busulfan, anagrelide and other drugs, and phlebotomy. Interferon and histone acetylation enzyme inhibitor might be used as well.Citation12 For HAPC, however, it is of vital importance to move to the plain. In this case, the patient moved to the plain and received phlebotomy therapy, supplementing with antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy, but without glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive treatment. Along with the fall in hemoglobin levels, the condition of proteinuria improved dramatically. Therefore, for patients with HAPC-induced FSGS who presented with NS, conventional therapies including glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive drugs are not recommended. Treatments for HAPC are crucial for the reduction of proteinuria and renal protection.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- D’Agati VD, Fogo AB, Bruijn JA, Jennette JC. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:368–382

- Finazzi G, Barbui T. The treatment of polycythemia vera: an update in the JAK2 era. Intern Emerg Med. 2007;2:13–18

- Beall CM, Cavalleri GL, Deng L, et al. Natural selection on EPAS1 (HIF2α) associated with low hemoglobin concentration in Tibetan highlanders. PNAS. 2010;107:11459–11464

- Haas M, Meehan SM, Karrison TG, Spargo BH. Changing etiologies of unexplained adult nephrotic syndrome: a comparison of renal biopsy findings from 1976–1979 and 1995–1997. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:621--631

- Rennke HG, Klein PS. Pathogenesis and significance of nonprimary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;13:443--456

- Kosch M, August C, Hausberg M, et al. Focal sclerosis with tip lesions secondary to polycythemia vera. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(10):1710–1711

- Mary FM. Idiopathic erythrocytosis: a disappearing entity. Hematology. 2009;1:629–635

- Kapitsinou PP, Liu Q, Unger TL, et al. Hepatic HIF-2 regulates erythropoietic responses to hypoxia in renal anemia. Blood. 2010;116(16):3039–3048

- Moore LG. Human genetic adaptation to high altitude. High Alt Med Biol. 2001;2(2):257–279

- Martha W, Ayalew T. Classification and diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms according to the 2008 World Health Organization criteria. Int J Hematol. 2010;91:174–179

- Sukru U, Gulsum O, Mehmet S, et al. Absence of hypoalbuminemia despite nephrotic proteinuria in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis secondary to polycythemia vera. Intern Med. 2010;49:2477–2480

- Claire H. Rethinking disease definitions and therapeutic strategies in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. Hematology. 2010;1:129–134