Abstract

Introduction: Impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and being in a depressive mood were found to be associated with increased mortality in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients. We aimed to investigate the association between HRQoL, depression, other factors and mortality in PD patients. Materials and methods: Totally 171 PD patients were included and followed for 7 years in this prospective study. Results: Of 171 PD patients, 45 (26.3%) deceased, 18 (10.5%) maintained on PD, 87 (50.9%) shifted to hemodialysis (HD) and 21 (12.3%) underwent transplantation. The most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease (32, 71.1%) followed by infection (6, 13.3%), cerebrovascular accident (5, 11.2%). The etiology of patients who shifted to HD was PD failure (41, 47.1%), peritonitis (33, 37.9%), leakage (6, 6.9%), catheter dysfunction (3, 3.4%), self willingness (4, 4.6%). Non-survivors were older than survivors (56.6 ± 15.0 vs. 43.6 ± 14.6, p = 0.003). There were also statistically significant difference in terms of albumin, residual urine, presence of diabetes and co-morbidity. When the groups were compared regarding HRQoL scores, non-survivors had lower physical functioning (p < 0.001), role-physical (p = 0.0045), general health (p = 0.004), role-emotional (p = 0.011), physical component scale (PCS) (p = 0.004), mental component scale (MCS) (p = 0.029). Age, presence of residual urine, diabetes, albumin, PCS and MCS were entered in regression analysis. Decrease of 1 g/dL of albumin and being diabetic were found to be the independent predictors of mortality. Conclusions: Diabetes and hypoalbuminemia but not HRQOL scores were associated with higher mortality in PD patients after 7 years of following period.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) receiving hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD).Citation1 Despite the improvements in PD, the impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and being in a depressive mood were found to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality in this population. Factors associated with increased mortality in PD patients have been examined in previous longitudinal studies.Citation2,Citation3 Multiple factors including inflammation, nutritional status and systemic diseases including diabetes are known to influence mortality and HRQoL in this population.Citation4 In light of the previous studies, being men and having diabetes but not increased age, co-morbidity, body mass index (BMI) were found to be associated with higher mortality rates in PD patients.Citation5–8

However, to date in the literature, there has been no study demonstrating the effects of HRQoL scores on mortality in PD patients. Hence, we aimed to investigate the differences between surviving and non-surviving PD patients and sought to determine the predictors of mortality including HRQoL, depression and other factors in this population.

Materials and methods

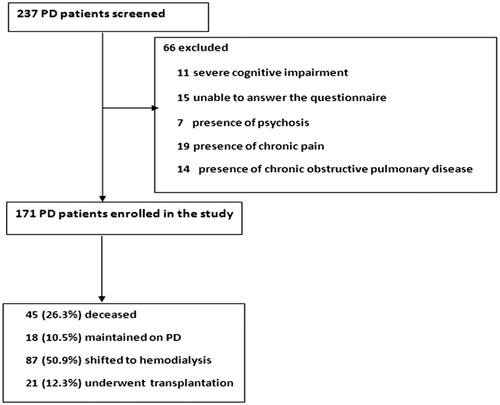

We performed a prospective study of patients with ESRD receiving PD. Patients were enrolled from three dialysis units, one located within Selcuk University Hospital and two located in various communities across a 100-km radius from city center of Konya. Patients between 17 and 84 years of age and willing to participate in the study for the assessment of HRQoL were evaluated. A review of medical records including information on age, sex, weight, duration of renal replacement treatment, medications and primary disease of ESRD was undertaken. Exclusion criteria included (1) severe cognitive impairment, (2) unable to answer the questionnaire, (3) presence of psychosis, (4) presence of chronic pain, (5) presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A flowchart regarding the exclusion criteria of PD patients was shown in . A total of 171 ESRD patients receiving PD were included and followed for 7 years between 2005 and 2012 in this prospective study ().

Venous blood samples for biochemical analyses were drawn after an overnight fast before first exchange in PD patients. All of the PD patients were in fasting state while blood samples were drawn. All biochemical analyses including plasma creatinine, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were performed with an oxidase-based technique by Roche/Hitachi Modular System (Mannheim, Germany) in the Central Biochemistry Laboratory. All of the analyses of PD were done in the same time of the year.

All patients used the same conventional 1.36%, 2.27% and 3.86% glucose-based lactate buffered and 1.25% calcium containing PD solutions from the Baxter Healthcare (Deerfield, IL). None of the patients used amino-acid or icodextrin containing PD solutions.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional medical ethics committee of Selcuk University and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects included in the study.

Evaluation of HRQoL

In order to evaluate HRQoL of the patients, we used the Short Form of Medical Outcomes Study (SF-36).Citation9 The test consists of 36 items, which are assigned to 8 dimensions, namely, physical functioning (10 items), role-physical (4 items), bodily pain (2 items), general health status (5 items), vitality (4 items), social functioning (2 items), role-emotional (3 items) and mental health (5 items). Each scale is scored with a range from 0 to 100. All but one of the 36 items (self-reported health transition) is used to score the eight SF-36 scales. While the first four dimensions constitute the physical component scale (PCS), the remaining four dimensions constitute the mental component scale (MCS). It has been shown that these two summary scales adequately represent values of their individual scale components with an 80% and 85% variability.Citation10 The higher the scale, the better is the HRQoL. This scale has been commonly used and validated in patients with ESRD.Citation11

Evaluation of depression

Depression was assessed by using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which had been validated and commonly used in patients with ESRD.Citation12,Citation13 The validation and reliability study in a Turkish population were made by HisliCitation14 and a BDI score of 17 or greater was determined as a cut-off value for the diagnosis of depression according to this study. In the present study, patients with BDI scores ≥17 were assumed as depressive patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Parametric data are the mean ± SD. The normal distributions of all variables were tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. Dichotomous variables were compared using the chi-square test or the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Statistical differences between parametric data of two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine differences between non-parametric data. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to examine associations between continuous variables. Multivariate linear regression analyses were undertaken to identify independent associations between mortality and other variables. Age, presence of residual urine, and diabetes, albumin, PCS and MCS were entered into the regression model as independent variables; mortality was entered as the dependent variable. The backward elimination method was preferred in the stepwise regression analysis and p > 0.1 used as a criterion for elimination in the model. The level of significance (p value) was 0.05 for all comparisons. p < 0.05 being considered significant for all tests.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

Of 171 PD patients, 45 (26.3%) deceased, 18 (10.5%) maintained PD, 87 (50.9%) shifted to HD, and 21 (12.3%) underwent renal transplantation (RT). The most common cause of death was CVD (32, 71.1%) followed by sepsis (6, 13.3%) and cerebrovascular accident (5, 11.2%). The etiology of patients who shifted to HD was PD failure (41, 47.1%), peritonitis (33, 37.9%), peritoneal leakage (6, 6.9%), peritoneal catheter dysfunction (3, 3.4%) and self willingness (4, 4.6%).

When we compared surviving and non-surviving patients, there was no statistically significant difference between two groups in terms of gender, BMI, hemoglobin, serum creatinine, calcium, phosphorus, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglyceride, parathormone levels, C-reactive protein (CRP), Kt/v, PD duration, education and employment status (p > 0.05 for all) ( and ). Non-survivors were found to be older than survivors (56.6 ± 15.0 vs. 43.6 ± 14.6, p = 0.003). There were also statistically significant difference between two groups in terms of serum urea and albumin, residual urine, presence of diabetes and co-morbidity (p = 0.002, p = 0.0047, p = 0.001, p = 0.001, respectively) ( and ).

Table 1. Socio-demographic and clinical features of PD patients.

Table 2. Laboratory values of surviving and deceased PD patients.

HRQoL of life scores of PD patients

When the groups were compared regarding HRQoL scores, non-survivors had lower physical functioning (59.3 ± 26.1 vs. 81.7 ± 21.4, p < 0.001), role-physical (21.7 ± 35.6 vs. 43.1 ± 42.7, p = 0.0045), general health (30.6 ± 15.0 vs. 39.8 ± 18.9, p = 0.004), role-emotional (17 ± 35.3 vs. 44.4 ± 45.7, p = 0.011), PCS (46.4 ± 20.2 vs. 62 ± 15.9, p = 0.004), MCS (35.5 ± 17.7 vs. 50 ± 19.2, p = 0.029) ().

Table 3. HRQoL, BDI Scores of surviving and deceased PD patients.

BDI scores of PD scores

Total, somatic and cognitive BDI scores of surviving and deceased PD patients were not found to be statistically significant (p > 0.05 for all). Both of two groups were found to be depressive according to total BDI scores ().

Predictors of mortality in PD patients

Age, serum albumin, presence of residual urine and diabetes, PCS and MCS were entered in the model of Cox-regression analysis. Among these parameters, decrease of 1 g/dL of albumin and being diabetic were found to be the independent predictors of mortality ().

Table 4. Independent predictors of mortality in PD patients.

Discussion

After 7 years of following the PD patients, the main findings of the present study were as follows: (1) CVDs were found to be the main cause of mortality in PD patients, (2) most of the PD patients were shifted to HD and PD failure was the most common factor responsible for this change, (3) when surviving and non-surviving patients were compared, non-survivors were found to be older, hypoalbuminemic, more uremic and had lower Kt/v and health-related quality parameters including general health status, role-physical, role-emotional, physical functioning, total SF-36 scores, mental and PCSs, (4) independent predictors of mortality in PD patients were found to be diabetes and hypoalbuminemia.

Previous studies demonstrated that CVDs, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition and decreased renal residual function are the main factors that are responsible for increased mortality in PD patients.Citation15,Citation16 Our results were in accord with these studies. We found that most of PD patients were died secondary to CVDs. Non-surviving PD were more diabetic, had decreased renal residual function and lower serum albumin levels when compared with surviving PD patients.

According to the U.S. Renal Data System database, approximately 19% of PD patients were shifted to HD over the 2-year period, translating to an annual mean rate of 9.5%.Citation17 PD to HD switch rates of 35% have been reported in the first 2 years in the USA.Citation18 Our study demonstrated that 50.9% of the PD patients transferred to HD over the 7-year period that means approximately annual mean rate of 7.3%. In the following period of 7 years, most of our PD patients were transferred to HD because of inadequate PD and peritonitis especially to maintain patient’s survival in patients who were not suitable for RT. Among other factors responsible for the shift were as follows: peritoneal leakage, self willingness, catheter dysfunction in the present study. Previous studies support our data regarding the reasons of transfer to HD.Citation19,Citation20 These studies have identified the most frequent causes of shift from PD to HD as infection, catheter problems, inadequate dialysis and psychosocial factors.Citation21 In a meta-analysis of four cohorts including approximately 40.000 PD patients, the authors identified the main causes for transfer from PD to HD as infection (28%), inadequate dialysis (18%), catheter problems (17%), psychosocial factors (15%) and other factors (22%).Citation22 These results might be the answer of the underutilization of PD worldwide and in Turkey as a renal replacement therapy. Hence, strategies to prevent PD and ultrafiltration failure, peritonitis, peritoneal leakage, catheter dysfunction and education of patients and medical staff might improve PD utilization as a renal replacement therapy.Citation23 Survival advantages were found to be determined in PD patients when compared with HD patients especially in the first 2 years of the dialysis treatment. In a study comparing 4568 HD and 2443 PD patients, Heaf et al.Citation24 also found a survival advantage for PD during the first 2 years of dialysis treatment that has also been reported among Canadian patients.Citation25 Therefore, starting patients on PD as their initial treatment modality especially in the first 2 years and if the complications mentioned above occurs switching these patients to other renal replacement therapies might be wise.

Another findings from our study were as follows: deceased PD patients were older and hypoalbuminemic, had lower Kt/v and health-related quality parameters including general health status, role-physical, role-emotional, physical functioning, total SF-36 scores, mental and PCSs.

In recent studies, it has been reported that many factors including, blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, heart rate variability, anemia, attacks of peritonitis as well as variability of serum calcium, phosphorus and parathormone are closely associated with clinical outcomes and mortality in ESRD patients receiving PD and HD.Citation26,Citation27 In addition, serum albumin levels were found to be an independent predictor of mortality in recent studies in this population.Citation28,Citation29 The main reason for hypoalbuminemia commonly seen in PD patients is the loss of serum albumin approximately 4 g/day through peritoneal effluent.Citation30 In health, the albumin losses might be compensated via increased synthesis in liver. However, this process can be interrupted in the inflammation era. Hence, KaysenCitation31 advocated that hypoalbuminemia can be considered as a marker of comorbidity and illness rather than a marker of malnutrition.Citation32,Citation33 Although hypoalbuminemia may reflect a high inflammatory status that determines outcome, factors such as advanced age, diabetes and serum albumin levels were found to be the main predictors of mortality.Citation34,Citation35 In a study on 298 PD patients, systolic heart failure was found to be strongly associated with diabetes and hypoalbuminemia, factors that were also predictors of mortality in this population.Citation36

In a retrospective cohort study the significant risk factor was diabetes mellitus in PD patients.Citation37 In a recent study done by Malyszko et al.,Citation29 PD patients with a high severity score of cardio-renal-anemia syndrome, were found to be more hypoalbuminemia, higher inflammation markers, and certainly were more anemic and diabetic, with higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. In this study, authors also concluded that albumin, a negative marker of inflammation, was a predictor of death in PD patients. Vikrant et al.Citation26 also confirmed that the mortality in PD patients without diabetes was less than that in PD patients with diabetes. According to the results of this study, the main cause of mortality in PD patients was cardiac followed by sepsis.Citation26

However, recently, Madziarska et al.Citation38 found that the only factor significantly associated with mortality was older age in PD patients.

Our results are in accord with these studies. In the present study, we also found that hypoalbuminemia and diabetes are the two main predictors of mortality in PD patients.

We previously demonstrated that PD patients had lower role-physical, general health status, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, mental health dimensions, and both physical and mental components of HRQoL when compared to HD patients.Citation39 In the present study, when compared to deceased PD patients, surviving PD patients had higher general health status, role-physical, role-emotional, physical functioning, total SF-36 scores, mental and PCSs. However, there were no differences between two groups in terms of BDI scores. Additionally, HRQoL scores were not found to be associated with increased mortality in the linear regression analysis.

Our study has some limitations. First, the study sample is relatively small. Second, in the following period of 7 years, we had no data regarding peritonitis attacks of patients. Third, we did not include automated PD patients. A multicenter prospective observational study of PD patients that is powered using effect sizes demonstrated here is needed to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, the present study reconfirmed that factors like diabetes and serum albumin levels but not HRQoL scores are the main predictors of mortality in PD patients.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- United States Renal Data System. USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2006

- Roderick P, Davies R, Jones C, Feest T, Smith S, Farrington K. Simulation model of renal replacement therapy: predicting future demand in England. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(3):692–701

- Chandna SM, Schulz J, Lawrence C, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. BMJ. 1999;318(7178):217–223

- Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(7):1955–1962

- Davies SJ. Longitudinal relationship between solute transport and ultrafiltration capacity in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2004;66(6):2437–2445

- Davies SJ, Phillips L, Naish PF, Russell GI. Quantifying comorbidity in peritoneal dialysis patients and its relationship to other predictors of survival. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(6):1085–1092

- Churchill DN, Thorpe KE, Nolph KD, Keshaviah PR, Oreopoulos DG, Page D. Increased peritoneal membrane transport is associated with decreased patient and technique survival for continuous peritoneal dialysis patients. The Canada-USA (CANUSA) Peritoneal Dialysis Study Group. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(7):1285–1292

- Rumpsfeld M, McDonald SP, Purdie DM, Collins J, Johnson DW. Predictors of baseline peritoneal transport status in Australian and New Zealand peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(3):492–501

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483

- Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(4 Suppl):AS264–AS279

- Johansen KL, Painter P, Kent-Braun JA, et al. Validation of questionnaires to estimate physical activity and functioning in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;59(3):1121–1127

- Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int. 2000;57(5):2093–2098

- Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith R, Concato J. The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(1):105–110

- Hisli N. Beck Depresyon Envanterinin geçerliliği üzerine bir çalışma. Psikoloji Dergisi. 1998;6:118–22

- Cueto-Manzano AM, Quintana-Pina E, Correa-Rotter R. Long-term CAPD survival and analysis of mortality risk factors: 12-year experience of a single Mexican center. Perit Dial Int. 2001;21(2):148–153

- Collins AJ, Hao W, Xia H, et al. Mortality risks of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34(6):1065–1074

- U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-stage Renal Disease in the United States B. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease; 2009

- Guo A, Mujais S. Patient and technique survival on peritoneal dialysis in the United States: evaluation in large incident cohorts. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003 (88):S3–S12

- Van Biesen W, Dequidt C, Vijt D, Vanholder R, Lameire N. Analysis of the reasons for transfers between hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis and their effect on survivals. Adv Perit Dial. 1998;14:90–94

- Da Silva-Gane M, Wellsted D, Greenshields H, Norton S, Chandna SM, Farrington K. Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):2002–2009

- Ersoy FF. Improving technique survival in peritoneal dialysis: what is modifiable? Perit Dial Int. 2009;29(Suppl 2):S74–S747

- Mujais S, Story K. Peritoneal dialysis in the US: evaluation of outcomes in contemporary cohorts. Kidney Int Suppl. 2006 Nov(103):S21–S26

- Chaudhary K, Sangha H, Khanna R. Peritoneal dialysis first: rationale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(2):447–456

- Heaf JG, Lokkegaard H, Madsen M. Initial survival advantage of peritoneal dialysis relative to hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(1):112–117

- Fenton SS, Schaubel DE, Desmeules M, et al. Hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis: a comparison of adjusted mortality rates. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30(3):334–342

- Vikrant S. Long-term clinical outcomes of peritoneal dialysis patients: 9-year experience of a single center from North India. Perit Dial Int. 2014 Jan 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- Rhee C, Molnar M, Lau WL, et al. Comparative mortality-predictability using alkaline phosphatase and parathyroid hormone in patients on peritoneal dialysisand hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2014. [Epub ahead of print]

- Yang X, Yi C, Liu X, et al. Clinical outcome and risk factors for mortality in Chinese patients with diabetes on peritoneal dialysis: a 5-year clinical cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(3):354–361

- Malyszko J, Zbroch E, Mysliwiec M, Iaina A. The cardio-renal-anaemia syndrome predicts survival in peritoneally dialyzed patients. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(4):539–544

- Krediet RT, Zuyderhoudt FM, Boeschoten EW, Arisz L. Peritoneal permeability to proteins in diabetic and non-diabetic continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephron. 1986;42(2):133–140

- Kaysen GA. Biological basis of hypoalbuminemia in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(12):2368–2376

- de Mutsert R, Grootendorst DC, Indemans F, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT, Dekker FW. Association between serum albumin and mortality in dialysis patients is partly explained by inflammation, and not by malnutrition. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19(2):127–135

- Friedman AN, Fadem SZ. Reassessment of albumin as a nutritional marker in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(2):223–230

- Wang AY, Woo J, Lam CW, et al. Is a single time point C-reactive protein predictive of outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(7):1871–1879

- Blake PG, Flowerdew G, Blake RM, Oreopoulos DG. Serum albumin in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis – predictors and correlations with outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3(8):1501–1507

- Moretta G, Locatelli AJ, Gadola L, et al. Rio de La Plata study: a multicenter, cross-sectional study on cardiovascular risk factors and heart failure prevalence in peritoneal dialysis patients in Argentina and Uruguay. Kidney Int Suppl. 2008;(108):S159–S164

- Enriquez J, Bastidas M, Mosquera M, et al. Survival on chronic dialysis: 10 years' experience of a single Colombian center. Adv Perit Dial. 2005;21:164–167

- Madziarska K, Weyde W, Penar J, et al. Different mortality predictor pattern in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis diabetic patients in 4-year prospective observation. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2013;67:1076–1082

- Turkmen K, Yazici R, Solak Y, et al. Health-related quality of life, sleep quality, and depression in peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(2):198–206