Abstract

Fusarium is a filamentous opportunistic pathogenic fungus responsible for superficial as well as invasive infection in immunocompromized hosts. Net state of immunosuppression and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection appear to predispose to this disease which is life-threatening when disseminated. Though infections with Fusarium have been widely described in hematological malignancies and hematopoietic stem cell transplant cases, they have been reported to be rare in solid organ transplant recipients, are often localized and carry a favorable prognosis. We here describe a rare case of subcutaneous non-invasive infection with Fusarium in a renal allograft recipient two and half years after transplantation. Patient had a previous history of CMV infection along with multiple other recurrent co-infections. Diagnosis was based on culture of tissue specimens yielding Fusarium species. The infection had a protracted course with persistence of lesions after treatment with voriconazole alone, requiring a combination of complete surgical excision and therapy with the anti-fungal drug.

Introduction

Infections are one of the commonest causes of deaths after kidney transplantation.Citation1 Majority of the recipients suffers from at least one bacterial, fungal or viral infection in the first year. Fungal infections occur in 6–23% of kidney transplant recipients.Citation2–5 Most fungal infections are invasive and life threatening (e.g., Candia, Aspergillus species). Non-invasive infections of skin and subcutaneous tissues by moulds are rare. These localized or locally invasive forms may herald disseminated disease.Citation6

Fusarium is a plant pathogen and opportunistic human pathogenic mould. It has been commonly described in patients with hematological malignancies and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, especially with neutropenia.Citation7 It can cause superficial, locally invasive and disseminated infections. In neutropenic patients, fusariosis presents as disseminated infection with mortality rate more than 80%.

More than 50 species of Fusarium are identified but only a few are implicated to cause infection in humans.Citation7 Fusarium solani is the most frequent species contributing to about 50% of the cases. Other species include Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium verticillioidis and Fusarium moniliforme.Citation7

In solid organ transplant recipients, infection with Fusarium has been reported to be rare with most infections remaining localized and non-invasive. If treated early, these localized infections carry a favorable prognosis. It is not known if this disease entity is a precursor of the fatal disseminated form or is simply a reflection of the net state of immunosuppression.

We report a case of difficult-to-treat localized subcutaneous infection with Fusarium species in a kidney transplant recipient.

Case report

Forty-two-year-old female renal allograft recipient presented to the transplant outpatient clinic with multiple skin nodules around right elbow two and half years after the transplant surgery. The donor was her husband with haplotype HLA match. Although she had immediate and stable graft function after the transplant and was maintained on triple immunosuppressive therapy, comprising of tacrolimus, mycophenolate and prednisolone, she had been through a very event-filled post-transplant course after the first year. She had history of chronic diarrhea requiring mycophenolate withdrawal, followed by cytomegalovirus (CMV) gastritis and chronic graft dysfunction in the second year and sputum negative pulmonary tuberculosis in the third year after her surgery.

On examination, her skin nodules were mildly tender, non-erythematous, firm and smooth, with distinct margins and not fixed to the skin or bone. Overlying skin was intact with absence of regional lymphadenopathy. There was no history of trauma. Patient was normotensive and pale with otherwise normal systemic examination. Laboratory evaluation showed anemia, (Hemoglobin – 6.7 g/dL,) and graft dysfunction [serum creatinine 2.7 mg/dL (238.7 µmol/L)]. Liver function tests, chest radiograph and ultrasonography of abdomen were within normal limits. She had iron deficiency with transferrin saturation of 7% and tacrolimus trough level was 4 ng/mL.

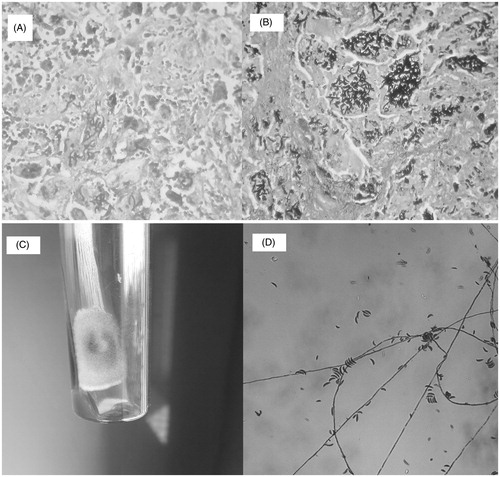

One of the nodules turned fluctuant over next few days. Pus drained from the nodule showed negative Gram and acid-fast stain but potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount revealed septate hyphae with branching at acute angle. Pus did not grow any organism on Sabouraud dextrose agar. Itraconazole 200 mg BD was started, but switched over to Voriconazole 200 mg BD in view of no response to former after 4 weeks. Voriconazole was given for 4 weeks. Size of the nodules decreased significantly although not completely. However after stopping therapy, the nodules re-acquired their original size over the next 1 month. Thereafter, all the lesions were excised surgically in two consecutive surgeries. The histopathology of the excised nodules showed fibrocollagenous tissue with florid granulomatous reaction. Amid the epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells were seen which were stuffed with branching septate fungal hyphae (). Culture of the excised tissue showed growth of Fusarium on cycloheximide free Sabouraud dextrose agar (). Voriconazole therapy was restarted and continued for 4 weeks. Patient was treated for iron deficiency and antituberculous therapy was continued. At 3 months, patient required surgical excision for recurrent nodules.

Figure 1. (A) Histopathology- granuloma with giant cell studded with fungal elements (H & E stain). (B) Histopathology- intracellular fungal hyphae (Gomori’s methenamine silver stain). (C) Growth on Sabouraud agar – fungal colony with cottony surface. (D) Growth on Sabouraud agar – banana-shaped macroconidia.

Discussion

Fusarium species are soil saprophytes and plant pathogens that cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised hosts, mainly in patients with hematological malignancies and recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In humans, fusariosis can present as a superficial infection involving skin or cornea, localized subcutaneous infection or disseminated infection with high mortality. Although disseminated fusariosis that occurs in neutropenic patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is relatively well documented,Citation8 research into the epidemiology of fusariosis after kidney transplantation deserves further attention.

We here report a case of non-invasive subcutaneous fungal infection with Fusarium in a renal allograft recipient in the late post-transplant period. Given the rarity of our findings coupled with previously published reports that point towards skin involvement being the portal of entry and precursor towards disseminated fusariosis,Citation6,Citation9 our case merits documentation.

Skin, when a portal of entry of fusarial infection, usually has history of trauma. Lesions are painful red or violaceous nodules which ulcerate and are covered by a black eschar.Citation9,Citation10 Of note, our patient did not have history of local trauma, nor did she have ulcerations over her lesions.

Several virulence factors described include synthesis of trichothecene, a mycotoxin which suppress humoral and cellular immunity and may also cause tissue breakdown and angioinvasion. Host defense is mainly in the form of innate immunity, damage to fusarial hyphae by macrophages and neutrophils primed by gamma interferon and growth factors.Citation11 Occurrence of disseminated fusariosis in hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients without neutropenia points towards a role of T-cells in host defence.

Diagnosis is usually established by histopathology of the tissue and isolation of the fungus in culture medium. Septate hyaline hyphae that branch at acute angle are seen in the tissue. A few other fungi, for example, Aspergillus and Scedosporium, have similar morphological appearance. Definitive diagnosis depends on culture in cycloheximide-free agar, for example, Sabouraud dextrose agar. Identification of species on morphology of macro- and micro-conidia can be difficult and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques are used for species identification.

Fusarium infections are rare after kidney transplantation. We could locate only five documented case reports of fusariosis in renal allograft recipients.Citation12–15,Citation17 In addition, a retrospective study by French Mycosis Study Group included a renal allograft recipient with invasive fusariosis;Citation8 details of this case were not available to us. Four patients with age 30–56 years developed non-invasive skin and subcutaneous fusariosis 6 months to 5 years after transplantation and one patient had Fusarium peritonitis diagnosed in the first week after transplantation. One patient had diabetes mellitus while two had CMV co-infection. All the cases were diagnosed with the help of fungal culture. In two cases treated with surgical excision alone and combined voriconazole and surgery, therapy was successful. One patient treated with itraconazole alone had partial clearance of the lesions. Disease persisted in a patient who was treated with surgery and amphotericin B. Patient with Fusarium peritonitis was treated successfully with voriconazole.

Thus, the best strategy for treatment remains elusive. The therapeutic options available include surgical excision and antifungal therapy. Fusarium is resistant to fluconazole, ketoconazole and echinocandins. They are susceptible to Amphotericin B, Voriconazole, posaconazole and relatively resistant to itraconazole. In our case, there was no response to itraconazole and only a partial response to voriconazole. Surgical excision was required multiple times. Thus, surgical excision coupled with voriconazole appears to be the prudent approach reported in kidney transplant recipients.Citation12–15 In other organ transplant recipients, this approach has been described to have 44% mortality.Citation16

It is known for long that CMV infection, by virtue of its immunomodulatory action, increases the risk of invasive fungal infections.Citation18,Citation19 Thirty percent of the solid organ transplant recipients with fusariosis had history of CMV infection.Citation20 Likewise, 36% of the liver transplant recipients with CMV disease had invasive fungal infection within first-year post-transplant.Citation18 Our patient was also diagnosed with CMV gastritis soon before presenting with fusarial infection and was treated successfully. In view of low immunological risk, our patient did not receive induction immunosuppression or CMV prophylaxis. However, administering “universal prophylaxis” for CMV does reduce the risk of fungal infections.Citation21

In contrast, prophylactic anti-fungal agents may not always protect against the infection.Citation16 Mortality in invasive non-Aspergillus hyalohyphomycosis is as high as 80%.Citation19 In a case series, Muhammed et al. noted mortality rate of about 36% attributed to skin fusariosis in patients with burns, hematological malignancies and in recipients of lung transplantation.Citation16 Fortunately, in non-invasive fusarial infections described in kidney transplant recipients, outcome appears to be favorable with combination therapy comprising surgery and subsequent treatment with antifungal agent voriconazole.Citation12–15

To conclude, Fusariosis is one of the rare causes of fungal infection in kidney transplant recipients. The limited literature available coupled with our own observations in our case point towards an association between the presence of underlying CMV infection and the development of Fusariosis in renal transplant recipients. In our case, there was also a history of multiple recurrent infections in the patient due to her immunosuppressed state. Given the paucity of epidemiological data available, it still remains to be discovered whether successful treatment of non-invasive Fusarial disease confers a survival advantage against the development of multiple infections in this highly immunocompromised patient cohort. It also remains to be established whether localized Fusarial infections are harbingers of a more lethal disseminated invasive form of the disease in kidney transplant recipients. To find definitive answers to these conundrums, more work still needs to be done in this area. Until then, prompt recognition, early diagnosis and appropriate therapy combining surgical excision and anti-fungal treatment is the best available recourse to non-invasive Fusarial infection in renal allograft recipients.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Dr. Anurag Kulkarni, Immunology section, Department of Medicine, Imperial College, London, for the valuable inputs.

References

- Briggs JD. Causes of death after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1545–1549

- Jha V, Chugh KS. Posttransplant infections in the tropical countries. Artif Organs. 2002;26:770–777

- Ram R, Dakshina Murty KV, Prasad N. Time table of infections after renal transplantation – South Indian experience. Indian J Nephrol. 2005;15:S14–S21

- Tharayil John G, Shankar V, Talaulikar G, et al. Epidemiology of systemic mycoses among renal transplant recipients in India. Transplantation. 2003;75:1544–1551

- John GT. Infections after renal transplantation in India. Indian J Nephrol. 2003;13:14–19

- Nucci M, Varon AG, Garnica M, et al. Increased incidence of invasive fusariosis with cutaneous portal of entry, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1567–1572

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:695–704

- Lortholary O, Obenga G, Biswas P, et al.; French Mycoses Study Group. International retrospective analysis of 73 cases of invasive fusariosis treated with voriconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4446–4450

- Gupta AK, Baran R, Summerbell RC. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2000;13:121–128

- Dignani MC, Anaissie E. Human fusariosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:67–75

- Gaviria JM, van Burik JA, Dale DC, Root RK, Liles WC. Comparison of interferon-gamma, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for priming leukocyte-mediated hyphal damage of opportunistic fungal pathogens. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1038–1041

- Young CN, Meyers AM. Opportunistic fungal infection by Fusarium oxysporum in a renal transplant patient. Sabouraudia. 1979;17:219–223

- Girardi M, Glusac EJ, Imaeda S. Subcutaneous Fusarium foot abscess in a renal transplant patient. Cutis. 1999;63:267–270

- Cocuroccia B, Gaido J, Gubinelli E, Annessi G, Girolomoni G. Localized cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis caused by a Fusarium species infection in a renal transplant patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:905–907

- Banerji JS, Singh J C. Cutaneous Fusarium infection in a renal transplant recipient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:205 . DOI:10.1186/1752-1947-5-205

- Muhammed M, Anagnostou T, Desalermos A, et al. Fusarium infection: report of 26 cases and review of 97 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2013;92:305–316

- Garbino J, Uckay I, Rohner P, Lew D, Van Delden C. Fusarium peritonitis concomitant to kidney transplantation successfully managed with voriconazole: case report and review of the literature. Transpl Int. 2005;18:613–618

- George MJ, Snydman DR, Werner BG, et al. The independent role of cytomegalovirus as a risk factor for invasive fungal disease in orthotopic liver transplant recipients. Boston Center for Liver Transplantation CMVIG-Study Group. Cytogam, MedImmune, Inc. Gaithersburg, Maryland. Am J Med. 1997;103:106–113

- Varani S, Landini MP. Cytomegalovirus-induced immunopathology and its clinical consequences. Herpesviridae. 2011;2:6 . DOI: 10.1186/2042-4280-2-6

- Husain S, Alexander BD, Munoz P, et al. Opportunistic mycelial fungal infections in organ transplant recipients: emerging importance of non-Aspergillus mycelial fungi. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:221–229

- Kalil AC, Levitsky J, Lyden E, Stoner J, Freifeld AG. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of strategies to prevent organ disease by cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:870–880