Abstract

Introduction and aims: Balkan endemic nephropathy (BEN), a regional tubulointerstitial kidney disease encountered in South-Eastern Europe, with still undefined etiology and inexorable evolution towards end stage renal disease, raises the question of the relative contribution of family and environmental factors in its etiology. In order to evaluate the intervention of these factors, markers of tubular injury have been assessed, this lesion being considered an early renal involvement in BEN. Methods: The paper studies relatives of BEN patients currently included in dialysis programmes (for involvement of the family factor) and their neighbors (for involvement of environmental factors) and analyzes them with regard to tubular injury by means of tubular biomarkers (N-acetyl-beta-d-glucosaminidase—NAG and alpha-1-microglobulin), and albuminuria. At the same time, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (CKD-EPI) was measured. It is considered that, in order to acquire the disease, one should have lived for 20 years in the BEN area. The relatives have been classified according to this criterion. Results: More evident tubular injury was found in the neighbors of BEN patients living for more than 20 years in the endemic area, which argues in favor of environmental factors. Higher levels of urinary alpha-1-microglobulin and albumin in relatives of BEN patients who had been living for more than 20 years in the area than in relatives with a residence under 20 years, plead for the same hypothesis. GFR was lower in persons who had been living for more than 20 years in the BEN area (neighbors and relatives). Conclusions: Environmental factors could be more important in BEN than family factors.

Introduction

Balkan endemic nephropathy (BEN) is a tubulointerstitial nephropathy encountered in several South-Eastern European countries: Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina. It is considered a regional disease, its name originating in the position of these countries in the Balkan Peninsula. First described more than 50 years ago, it has endemic character in the affected regions, located on the banks of the Danube and its tributaries. The disease is found mainly in rural areas, mostly in women whose predominant occupation is agriculture.

The etiology of BEN remains elusive. Familial occurrence is the characteristic of the disease. Environmental factors are also involved; persons living in the BEN area for 20 years can develop BEN.Citation1

Several hypotheses regarding the etiology of BEN have been forwarded. Some of them refer to environmental factors, others incriminate genetic factors.

The aristolochic acid hypothesis, generally accepted at present, considers that people within the endemic area used to eat bread made of wheat contaminated with seeds of Aristolochia clematitis, a plant identified in local wheat fields.Citation1 Another hypothesis refers to the use of therapeutic remedies prepared of Aristolochia clematitis (herbal teas, external baths, and cataplasms) in the endemic areas (The Mehedinti County, the main endemic focus in Romania).Citation2

High frequency of tumors of the urothelium in BEN patients was also identified when a related plant, Aristolochia fangchi, was used in therapeutic remedies for slimming diets. This plant is included in the category of the so-called Chinese herbs.

The nephropathy caused by Chinese herbs is also a tubulointerstitial nephropathy accompanied by tumors of the urothelium, being very similar to BEN.Citation3–5

Other hypotheses incriminate noxious substances in coal dating from the Pliocene, frequently found in the endemic area, mycotoxins—mainly ochratoxin A, slow acting viruses, metals, irradiation, etc.Citation6,Citation7

The family character of the disease attracted attention from the very beginning. In the endemic area there are families with several cases of BEN. Between 1960 and 1970 whole households died of this disease. The affected localities had an impressive aspect, with abandoned houses whose inhabitants had either died or left the locality. Those who had been living for more than 20 years in the endemic area developed BEN later and died of it in the locality they had moved to.Citation8

It is to be noted that people who are born outside the endemic area but immigrate to it and live there for about 20 years may also develop the disease, a fact which argues in favor of the intervention of environmental factors.

Numerous epidemiological and biochemical studies aimed at discovering the cause of the disease were conducted. Chromosomal and molecular-biological alterations have been described.Citation9,Citation10 These findings could not demonstrate indubitable participation of genetic factors. However, an ethnic character of the disease is to be noticed, the Roma population presenting no BEN.

The aspect of the disease has greatly changed nowadays, its evolution being much more benign.Citation11 If formerly the disease was diagnosed in persons 30–40 years old, rapidly becoming terminal, nowadays it is generally diagnosed at more advanced ages, 40, 50 or even 60 years.

At the beginning, there were no dialysis centers in the area. When they appeared, they prolonged the life of the patients.

Although some observations suggest a tendency towards reduced frequency of the disease, some authors show that new cases of BEN still appear.Citation11–13

Analysis of dialysis centers in the city of Drobeta-Turnu Severin (Romania) shows that about half of the dialyzed patients come from the BEN area, being diagnosed with this disease.

Currently, the objective is early diagnosis of the disease. Since BEN is a tubulointerstitial disease, markers of tubular injury are predominantly used.

Assessment of these tubular biomarkers aims at offering information about the prevalence of the disease in the investigated area.Citation11 Another studied parameter is the glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

Objectives

The aim of our study was to assess the contribution of the role of family and environmental factors in the etiology of BEN. It is to be noted that BEN affects only certain members of a family, which indicates genetic predisposition with possible interrelation with environmental factors. To this aim we studied comparatively relatives of BEN patients who had been living for less and more than 20 years in the endemic area (taking into consideration that it takes about 20 years in the BEN area to get the disease) and neighbors of BEN patients.

In the first two groups we evaluated the familial factor in relation to various time exposures to environmental factors, while in the third group (neighbors) the role of the environmental factors was assessed independently of family factors.

Methods

We designed four study groups, as follows:

Group 1 comprised 34 relatives of BEN patients who had lived more than 20 years in the BEN area.

Group 2 comprised 20 relatives of BEN patients who had lived less than 20 years in the BEN area.

We included in our study only first- and second-degree relatives of BEN patients currently under dialysis, with confirmed BEN diagnosis.

Group 3 comprised 19 neighbors of BEN patients who had lived more than 20 years in the BEN area.

In our study we classified as neighbors persons inhabiting the same locality, having their household in the proximity of the dwelling place of BEN patients; none of the neighbors under study had been diagnosed with BEN.

The control group consisted of 20 subjects from outside the BEN region.

All subjects were tested for serum creatinine and for urinary N-acetyl-beta-d-glucosaminidase (NAG), albumin and alpha-1-microglobulin.

N-acetyl-beta-d-glucosaminidase (NAG) was assessed with a colorimetric kit (Roche, Germany (No. 875-406)). The limit of detection was 0.01 U/L.

Urinary albumin was assessed with the Albumin-ELISA kit K6330 (Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany). The colored compound resulted was quantified by reading its absorbance at 450 nm. The limit of detection was 12.5 mg/L.

Urinary alpha-1-microglobulin was measured using the alpha-1-microglobulin ELISA kit K6710 (Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany). The limit of detection was 6 μg/L.

Because we used spot urine samples, we used creatinine values to correct for variability in urinary eliminations of NAG, albumin and alpha-1-microglobulin. Urinary biomarkers were expressed as U/g urinary creatinine in the case of NAG, and mg/g urinary creatinine in the case of albumin and alpha-1- microglobulin.

We also assessed the GFR in these persons by the CKD-EPI equation.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between the study groups were done using the Wilcoxon test (SPSS 20, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

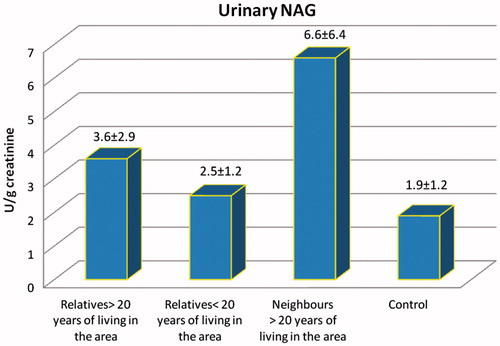

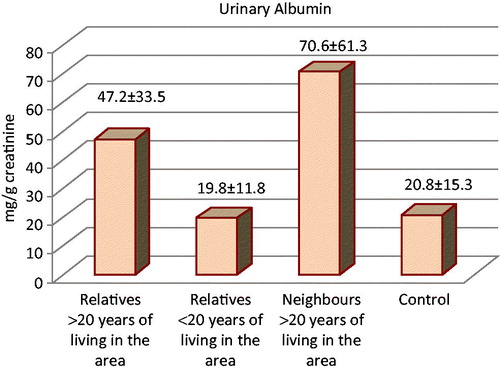

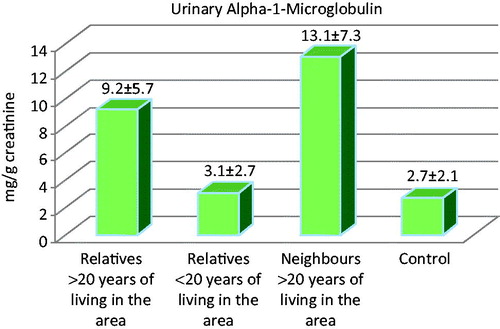

The urinary biomarkers of the investigated subjects are shown in and .

Table 1. Urinary biomarkers in BEN.

Group 1: Relatives of BEN patients with over 20 years residence in the BEN area had a mean age of 50.2 ± 14.4 years. Of these, 15 (44%) were female and 19 (56%) were male.

The average length of residence in the BEN area was 43.61 ± 17.04 years.

Only one person (4%) had used external remedies based on aristolochic acid.

Relatives of BEN patients who had lived over 20 years in the BEN area had higher values of NAG, albumin and alpha-1-microgobulin than controls (p= 0.01; p = 0.001; and p = 0.03 respectively).

Their values of alpha-1-microglobulin and albumin were also higher than those of relatives of BEN patients with less than 20 years residence in the BEN area (p = 0.02; p < 0.001).

Urinary NAG in relatives of BEN patients with residence of more than 20 years in BEN area was neither higher than that of relatives with length of residence under 20 years in the BEN area (p = 0.14) nor than that of the neighbors (p = 0.07).

Relatives of BEN patients who lived more than 20 years in the BEN region had higher values of albumin than relatives of BEN patients who had lived less than 20 years in the region (p < 0.001), but similar to those of the neighbors (p = 0.25).

Urinary alpha-1-microglobulin in relatives of BEN patients with more than 20 years residence in the BEN region was significantly higher than that of relatives with less than 20 years of residence and lower than that of the neighbors (p = 0.02, p = 0.03 respectively).

We found an indirect correlation between GFR and urinary NAG (r = −0.37; p = 0.03.), between GFR and urinary albumin (r = −0.53; p = 0.001.), and between GFR and urinary alpha-1-microglobulin in the urine (r = −0.54; p = 0.0009).

Group 2: Relatives with less than 20 years residence in the BEN area had a mean age of 35.40 ± 11 years, significantly lower than that of the relatives with more than 20 years in the BEN area. This difference is related to the fact that all persons investigated came from the BEN area, having lived there since birth, those who had lived there less than 20 years being younger. Of these, 13 (65%) were female and 7 (35 %) were male.

No person used remedies based on aristolochic acid.

Relatives of BEN patients with less than 20 years residence in the BEN area did not have higher values of NAG, albumin and alpha-1-microglobulin than controls (p = 0.3; p = 0.81; and p = 0.6 respectively).

Urinary NAG in relatives with less than 20 years residence in the BEN area was not lower than in relatives with more than 20 years residence in the area (p = 0.14) but it was lower than in neighbors (p = 0.01).

Urinary albumin in these persons was lower than in relatives with more than 20 years residence in the BEN area (p < 0.001) and in neighbors (p = 0.01).

Urinary alpha-1-microglobulin was lower than in relatives with more than 20 years in the BEN area (p = 0.02) and in neighbors (p < 0.001).

Group 3: Neighbours of BEN patients had a mean age of 61.70 ± 13.7 years. Of these, 13 (68%) were female and 6 (32 %) were male.

Seven persons (37%) had used external remedies based on aristolochic acid and two persons had (11%) used them internally.

The GFR in the neighbors of BEN patients was significantly lower than in both relatives with more than 20 years residence in the BEN area (p = 0.008) and in relatives with less than 20 years in the BEN area (p < 0.001).

Neighbors of BEN patients had higher values of NAG, albumin and alpha-1-microglobulin than controls (p = 0.005; p = 0.02; and p = 0.03 respectively) and relatives of BEN patients with less than 20 years residence in the BEN area (p = 0.01; p = 0.01; and p < 0.001 respectively), and higher values of alpha-1-microglobulin than relatives of BEN patients with more than 20 years residence in the area (p = 0.03).

Group 4: Controls had a mean age of 56.3 ± 6 years.

Discussion

Our study intended to assess the intervention of environmental or familial factors on persons living in the BEN area.

Our study found in neighbors of BEN patients much higher levels of the urinary biomarkers NAG, alpha-1-microglobulin and albumin than in controls. This argues in favor for a possible action of environmental toxic factors.

Neighbors of BEN patients had higher values of NAG, albumin and alpha-1-microglobulin than controls and relatives of BEN patients who had lived less than 20 years in the BEN area, and higher values of alpha-1-microglobulin than relatives of BEN patients who had lived more than 20 years in the area.

This pleads for an action of environmental factors with noxious effects on the renal tubules, not for an important influence of family factors, which would cause higher values of urinary biomarkers in relatives of BEN patients.

It should be remembered that the neighbors of the BEN patients had been living in the BEN area for more than 20 years. This remark would also plead for a possible intervention of an environmental factor in producing tubular lesions which need a long period of action.

Neighbors used remedies based on aristolochic acid more frequently than relatives. Aristolochic acid is considered the main etiologic factor in BEN.Citation14–16 However, long-term exposure to aristolochic-acid-based therapeutic remedies is necessary for inducing BEN, whereas the persons in our study reported sporadic, short-term (usually one week) internal or external use. In no person did this use coincide with the moment of biomarker assessment, their use having taken place long before. This fact allows us to consider that they did not play a significant part in producing the tubular lesions found in the persons we studied.

Imamovic considers that microalbuminuria may be a useful marker for early tubular injury in individuals at risk of developing BEN.Citation17 The urinary proteomic analysis performed by Pešić et al. validated six proteins as markers of BEN: alpha-1-microglobulin, beta-2-microglobulin, alpha 2-glycoprotein, mannose binding lectin-2, protection of telomeres protein-1, and superoxide dismutase (C–Zn).Citation18 Gluhovschi et al. reported increased levels of urinary beta-2-microglobulin in inhabitants of the BEN area.Citation19 Comparing BEN patients with healthy controls, Stefanovic et al. consider that urinary beta 2-microglobulin has higher sensitivity and specificity than alpha-1-microglobulin.Citation20

The GFR was lower in neighbors of BEN patients than in both relatives of BEN patients having lived in the area for more than 20 years in the BEN area and in relatives of BEN patients having lived there for less than 20 years. Low GFR could be related to the length of residence in the endemic area. It is also related to the age of the patients, the individuals residing in the endemic area being older that those with less than 20 years of residence. This would also plead for prolonged exposure to an environmental factor with noxious, probably toxic, action on the people in the BEN area. Cukuranovic et al. studied for a 15-year period the GFR of 18 BEN patients who had undergone renal biopsy and reported its slow diminution.Citation21

Studies regarding the levels of GFR sometimes brought surprising remarks. Thus, Djukanovic et al. observed that BEN patients in early stages of the disease had significantly higher creatinine clearance than patients with other kidney diseases.Citation22

Urinary NAG, albumin and alpha-1-microglobulin in the relatives of the BEN patients with <20 years residence in the BEN area did not significantly differ from the control group, but were significantly lower than in the neighbors. This pleads for a possible action of toxic environmental factors, diminishing the probability of the action of a family factor.

The relatives of patients with >20 years residence had higher values of urinary NAG, alpha-1-microglobulin and albumin than the controls. This could plead for the action of family factors, of environmental factors or of both. By comparing the urinary biomarkers of the group of relatives with more than 20 years residence in the BEN area with the group of neighbors one would have expected for the intervention of a family factor to have worsened the tubular lesions in the relatives of the BEN patients, however the results did not indicate differences regarding NAG and albumin, and the values of alpha-1-microglobulin were even higher in the neighbors group. These data do not plead for the intervention of an additional family factor in the relatives of BEN patients.

Comparing the relatives of BEN patients with >20 years residence in the BEN area with those <20 years residence in the BEN area we found that relatives with more than 20 years residence had higher values of alpha-1-microglobulin and of albumin than relatives of BEN patients <20 years. Urinary NAG values were not significantly higher. These remarks also plead for a possible intervention of environmental factors, a family factor being irrelevant.

Tubular injury is more important in neighbors and in the relatives with >20 years residence in the BEN area. We do not have an explanation for this observation.

The urinary excretion of albumin is an important, early, frequently used, marker of kidney injury (diabetes, hypertension, etc.). In BEN relatives with <20 years residence in the BEN area the urinary excretion of albumin was lower than in BEN relatives with >20 years residence and in neighbors of BEN patients. Environmental factors seem to be more important, the neighbors and the relatives with >20 years residence having higher values than relatives with <20 years residence.

Values of urinary alpha-1-microglobulin higher in neighbors than in patients with >20 years residence in BEN area, also plead for a role of environmental factors.

Miljković et al. found that urinary excretion of albumin and beta 2-microglobulin in children from endemic settlements and from families affected by BEN was not different from those in control rural settlements.Citation23 Stefanovic et al. consider that urinary NAG seems to be a more sensitive and precocious marker of tubular injury in BEN.Citation24 In Bulgaria, Dimitrov et al. investigated renal clinical markers in the offspring of BEN families before the onset of the disease. Urine concentrations of total protein, albumin and beta 2-microglobulin were higher in BEN offspring.Citation25

Arsenović et al. consider that regular systematic check-up of endemic families could enable early detection of the disease and initiation of measures for slowing down the progression of chronic renal disease.Citation26

Radisavljević et al. report abnormal renal ultrasound as well as increased urine concentration of microalbumin, alpha-1-microglobulin and beta 2-microglobulin, only in BEN offspring, not in non-BEN offspring. According to Radisavljević, renal abnormalities in offspring of BEN patients may be an early marker of BEN.Citation27 Recently Hanjangsit et al. reported that family history of BEN was associated with ultrasound examination revealing diminished kidney size and width of cortex and could be used, like diminished GFR, in the early diagnosis of BEN.Citation28 These studies need confirmation because these changes could be related to processes of renal fibrosis absent in early BEN.

Our study highlights the necessity of periodical assessment of residents in BEN areas with regard to detecting the presence of this disease as early as possible.

Urinary biomarkers represent an efficient way to this aim and could detect early tubular injury in BEN.

Concomitant assessment of GFR and urinary biomarkers is recommendable and could prove useful during epidemiological studies. We would recommend the use of both albuminuria and of 1 or 2 tubular biomarkers (preferably NAG and urinary alpha-1-microglobulin) in BEN, as well as in other chronic kidney diseases.

Urinary biomarker assessment for detection and regular check-up of people in the BEN area is convenient and ensures wider addressability. Special attention should be paid to people at risk in the BEN area, such as the individuals examined in the present paper: neighbors and relatives of BEN patients.

We found a higher significance of environmental factors, without excluding the intervention of a familial factor.

We consider that one should not neglect data about this disease with severe evolution, accompanied by urothelial tumors, even if it has regional characteristics and limited incidence at present. BEN resembles Chinese-herb nephropathy, both diseases merging into a relatively new entity, the so-called aristolochic nephropathy, widely spread in Asia, especially in China. It is considered “a worldwide problem”.Citation29

Conclusions

Our study supports a potential intervention of one or more environmental factors on the kidney, namely the renal tubules, especially in persons who had been living in the BEN area for a long period of time (>20 years.)

The role of familial factors is not to be neglected.

BEN represents an important public health care issue in Romania and in other countries in the Balkan area. Thus, further research concerning tubular lesions in BEN is mandatory, in order to allow monitoring of the endemic area.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this paper was presented at the ERA-EDTA meeting Prague 2011. The authors thank Dipl-Eng. Daniel Sidea for IT technical assistance.

Gheorghe Gluhovschi involved in study design and writing of the paper; Mirela Modilca, Silvia Velciov, Cristina Gluhovschi, and Ligia Petrica involved in acquisition of data; Corina Vernic involved in statistical analysis and Adriana Kaycsa involved in lab determinations.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Emergency County Hospital Timisoara Romania.

References

- Grollman AP, Jelaković B. Role of environmental toxins in endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2817–2823

- Gluhovschi G, Margineanu F, Kaycsa A, et al. Therapeutic remedies based on Aristolochia clematitis in the main foci of Balkan endemic nephropathy in Romania. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;116(1):c36–c46

- Cosyns JP. Aristolochic acid and ‘Chinese herbs nephropathy': A review of the evidence to date. Drug Safe. 2003;26(1):33–48

- De Jonge H, Vanrenterghem Y. Aristolochic acid: The common culprit of Chinese herbs nephropathy and Balkan endemic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(1):39–41

- De Broe ME. Chinese herbs nephropathy and Balkan endemic nephropathy: Towards a single entity, aristolochic acid nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):513–515

- Gluhovschi G, Margineanu F, Velciov S, et al. Fifty years of Balkan endemic nephropathy in Romania: Some aspects of the endemic focus in the Mehedinti county. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75(1):34–48

- Pfohl-Leszkowicz A. Ochratoxin A and aristolochic acid involvement in nephropathies and associated urothelial tract tumors. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2009;60(4):465–483

- Batuman V. Fifty years of Balkan endemic nephropathy: Daunting questions, elusive answers. Kidney Int. 2006;69(4):644–646

- Toncheva D, Dimitrov T, Tzoneva M. Cytogenetic studies in Balkan endemic nephropathy. Nephron. 1988;48(1):18–21

- Stefanovic V, Toncheva D, Atanasova S, Polenakovic M. Etiology of Balkan endemic nephropathy and associated urothelial cancer. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26(1):1–11

- Bukvic D, Jankovic S, Maric I, Stosovic M, Arsenovic A, Djukanovic L. Today Balkan endemic nephropathy is a disease of the elderly with a good prognosis. Clin Nephrol. 2009;72(2):105–113

- Cvitković A, Vuković-Lela I, Edwards KL, et al. Could disappearance of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy be expected in the forthcoming decades? Kidney Blood Press Res. 2011;35(3):147–152

- Janković S, Bukvić D, Marinković J, Janković J, Marić I, Djukanović L. Time trends in Balkan endemic nephropathy incidence in the most affected region in Serbia, 1977–2009: The disease has not yet disappeared. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(10):3171–3176

- Schmeiser HH, Kucab JE, Arlt VM, et al. Evidence of exposure to aristolochic acid in patients with urothelial cancer from a Balkan endemic nephropathy region of Romania. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2012;53:636–641

- Hranjek T, Kovac A, Kos I, et al. Endemic nephropathy: The case for chronic poisoning by Aristolochia. Croaţia Med J. 2005;46(1):115–125

- Jelakovic B, Karanovic S, Vukovic-Lela I, et al. Aristolactam-DNA adducts are a biomarker of environmental exposure to aristolochic acid. Kidney Int. 2012;81:559–567

- Imamovic G, Batuman V, Sinanovic O, et al. Microalbuminuria as a possible marker of risk of Balkan endemic nephropathy. Nephrology (Carlton). 2008;13(7):616–621

- Pešić I, Stefanović V, Müller GA, et al. Identification and validation of six proteins as marker for endemic nephropathy. J Proteomics. 2011;74(10):194–200

- Gluhovschi G, Rosca A, Margineanu F, Grecu A, Tatu C, Paunescu V. The study of urinary beta-2 microglobulin in the diagnosis of Balkan endemic nephropathy. Nefrologia. 2003;8(20–21):81–90

- Stefanović V, Djukanović L, Cukuranović R, et al. Beta 2-microglobulin and alpha1-microglobulin as markers of Balkan endemic nephropathy, a worldwide disease. Ren Fail. 2011;33(2):176–183

- Cukuranovic R, Savic V, Stefanovic N, Stefanovic V. Progress of kidney damage in Balkan endemic nephropathy: A 15-year follow-up of patients with kidney biopsy examination. Renal Fail. 2005;27(6):701–706

- Djukanovic L, Bukvic D, Maric I. Creatinine clearance and kidney size in Balkan endemic nephropathy patients. Clin Nephrol. 2004;61(6):384–386

- Miljković P, Strahinjić S, Hall PW III, Djordjević V, Mitić-Zlatković M, Stefanović V. Urinary protein excretion in children from families with Balkan nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1991;34:27–31

- Stefanovic V, Cukuranovic R, Djordjevic V, Jovanovic I, Lecic N, Rajic M. Tubular marker excretion in children from families with Balkan nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(11):2155–2166

- Dimitrov P, Tsolova S, Georgieva R, et al. Clinical markers in adult offspring of families with and without Balkan Endemic Nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2006;69(4):723–729

- Arsenović A, Bukvić D, Djukanović L. One-year follow-up of renal function in endemic nephropathy families. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2009;137(1–2):27–32

- Radisavljević S, Peco-Antić A, Kotur-Stevuljević J, Savić O. Structural and functional characteristics of urinary tract in offspring of Balkan endemic nephropathy patients. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2010;138(3–4):204–209

- Hanjangsit K, Karmaus W, Dimitrov P, Zahng H, Tsolova S, Batuman V. The role of parental history of Balkan endemic nephropathy in the occurrence of BEN: A prospective study. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2012;5:61–68

- Debelle FD, Vanherweghem JL, Nortier JL. Aristolochic acid nephropathy: A worldwide problem. Kidney Int. 2008;74(2):158–169