Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to examine 2 cases of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis, occuring in 2 immunocompentent adult patients.

Methods: Case selection and literature review.

Results: Both patients cited significantly decreased vision despite systemic, topical, and/or local corticosteroid use. Neither patient was using high-dose immunosuppressant therapy at the time of diagnostic testing. Both patients exhibited confirmed CMV infection via polymerase chain reaction DNA testing. Oral antivirals were employed and have stabilized both patients.

Conclusion: The cases described herein serve to inform ophthalmologists of the urgent need to include CMV in their differential when encountering an immunocompetent adult with significant comorbidities or with a history of previous exposure. Proper treatment is heavily reliant on proper diagnosis.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is a sight-threatening form of posterior uveitis predominantly afflicting immunosuppressed individuals and infants. Few cases of CMV retinitis have been reported in healthy adults. We report 2 cases of CMV retinitis in immunocompetent adults and review the medical literature to identify possible factors that may increase susceptibility to the development of CMV retinitis.

Results

Case 1

A 61-year-old man presented with a 5-month history of light sensitivity in his left eye (OS) after being struck in the left eye while chipping ice with a shovel. His past medical history was significant for systemic hypertension, mitral valve prolapse, and aortic regurgitation. At presentation, his visual acuity was 20/30 in both eyes with a sluggish pupil reaction OS.

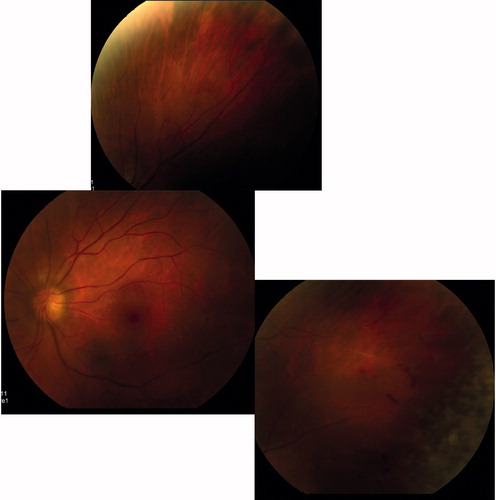

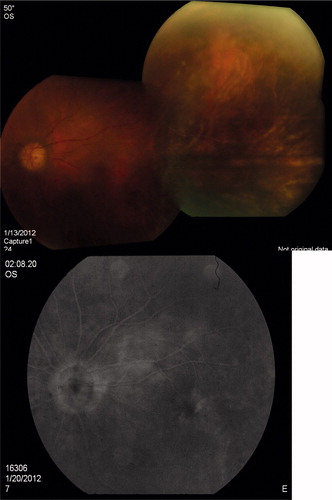

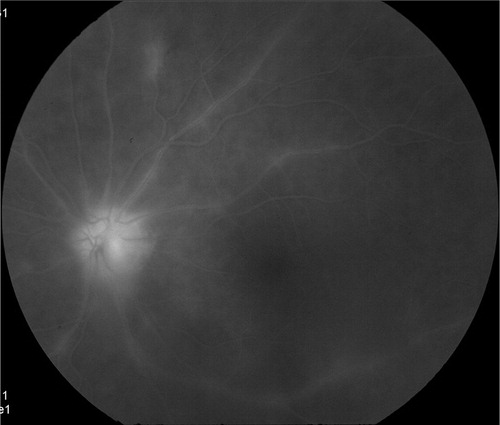

Anterior chamber cells were graded 1+ and vitreous cells were graded 2+. Funduscopy revealed superotemporal ghost arterioles and areas of confluent retinitis in the inferior peripheral retina with intraretinal hemorrhages (). Fluorescein angiography (FA) demonstrated widespread areas of peripheral retinal nonperfusion, optic disc hyperfluoresence, and retinal vascular staining ().

Figure 2. Late-phase fluorescein angiogram demonstrating optic disc hyperfluoresence and leakage of retinal arterioles and venules.

Diagnostic vitrectomy was planned, concurrent with a serologic evaluation. Three days prior to the vitrectomy, he returned with vision reduced to counting fingers accompanied by severe pain and redness with marked deterioration of his visual field OS due to severe panuveitis. Treatment was initiated with prednisone 40 mg daily per os. Vitreous biopsy performed 2 weeks later following reduction of prednisone to 10 mg daily revealed the presence of CMV DNA via qualitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR, Mayo Labs, Rochester MN); PCR studies for herpes simplex (HSV), varicella zoster (VZV), and toxoplasmosis were negative (Specialty Laboratories, Valencia CA). Infectious disease consultation was obtained; laboratory examination revealed that the patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, the CD4 count was 842 cells/mm3, and CMV IgG antibody (Ab) was present but CMV IgM Ab was not detected. The impression of the infectious disease consultant was that either the patient had underlying malignancy or the PCR results were a false positive.

Treatment consisted of intravitreal gancyclovir 2 mg injected weekly, along with oral valganciclovir 900 mg bid; the prednisone was tapered to 20 mg/day. Anterior uveitis resolved within 2 weeks and his vision improved to 20/70, while a repeat FA showed persistent vasculitis.

A dense vitreous hemorrhage with microhyphema OS developed following the third intravitreal injection. B-scan ultrasonography did not demonstrate any retinal tear or detachment. Vitrectomy with endolaser was recommended, but the patient developed pleuritic chest pain. Chest x-ray demonstrated bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and computed tomography imaging of the chest and abdomen revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary emboli with atelectasis. Hematology/oncology consultation was obtained and hypercoaguability workup revealed the presence of factor V Leiden mutation heterozygosity. Warfarin treatment was initiated. No malignancy was identified. The patient attributed the pulmonary emboli to anti-viral therapy and discontinued valganciclovir against our recommendations.

Four weeks later, the patient returned with recurrent hyphema and elevated intraocular pressure (36 mmHg OS) secondary to supratherapeutic international normalized ratio. Dorzolamide, timolol (Cosopt), and bimatoprost (Lumigan) were initiated and pan-retinal photocoagulation with intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) was performed. The patient returned with a hypopyon and corneal ulcer, which resolved following topical therapy with ganciclovir ointment and polysporine/trimethoprim ophthalmic solution.

One week later he returned with progression of retinitis threatening the fovea (). He was admitted for intravenous acyclovir therapy because the infectious disease consultant did not feel the patient had CMV disease. Anterior chamber paracentesis fluid was sent for PCR analysis, which again confirmed presence of CMV DNA; both HSV and VSV were again negative. Intravitreal gancyclovir 2.0 mg injections were given twice weekly with iv acyclovir 10 mg/kg/day for 1 week, followed by resumption of valganciclovir 450 mg bid despite reservations of the infectious disease consultant. Approximately 2 months later, the patient's vision (20/30 OU) and subsequent imaging studies showed improvement (). Cataract surgery was performed without complication or recurrence 6 months following vitrectomy with postoperative uncorrected visual acuity of 20/30. He is currently maintained on valgancyclovir 450 mg bid without recurrence for 15 months.

Case 2

A healthy 55-year-old man presented with a 3-year history of decreased vision in the right eye (OD). The referring ophthalmologist considered a diagnosis of idiopathic panuveitis OD, and administered 5 intravitreal triamcinolone injections over 3 years along with chronic topical corticosteroids. The patient was then treated with oral cyclosporine-A and mycophenolate mofetil. A visually significant cataract developed requiring extraction with intraocular lens implantation but no visual improvement was observed and he was referred for evaluation.

Uncorrected visual acuity was 20/300 OD and 20/20 OS. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the right eye revealed 4+ cells in the anterior chamber (AC) and 2+ vitreous cells and 3+ vitreous haze. Fluorescein angiography (FA) findings were limited by the extremely hazy media.

An AC paracentesis was positive for CMV DNA via PCR. Serum CMV IgG, HSV-IgG, and VZV-IgG were detected, while CMV IgM, HSV-IgM, and VZV-IgM levels were negative.

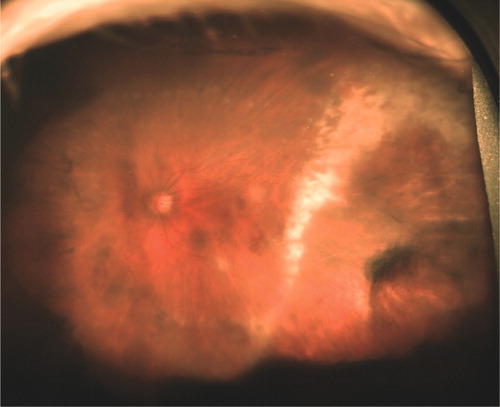

Intravitreal gancyclovir 2 mg weekly with oral valganciclovir 900 mg bid was instituted for 4 weeks without significant clinical improvement. Pars plana vitrectomy with Vitrasert (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester NY) was performed OS. Dense vitreous hemorrhage was present on the first postoperative day and persisted for 4 weeks. Vitrectomy with endolaser was planned, but the patient returned 3 days prior to the scheduled surgery due to sudden deterioration of vision. Total retinal detachment was diagnosed via ophthalmic B-scan ultrasonography. Pars plana vitrectomy with endolaser and silicone oil injection was performed.

At postoperative day 7, uncorrected visual acuity was 20/400 and the intraocular pressure was 10 mmHg. Funduscopy showed a 360-degree atrophic retina with pale disc and vitreous filled with silicone oil. He is currently maintained on valganciclovir 900 mg once daily and is clinically stable.

Discussion

Cytomegalovirus infection is common, with worldwide prevalence estimates of between 40 and 100% of young adults demonstrating serologic evidence of exposure by the fourth decade.Citation[1],Citation[2] Following primary infection, CMV disseminates hematogenously and may infect the retina and other areas of the central nervous system.Citation[3]

CMV progression is promoted by retinal vascular endothelial damage and reduced blood flow velocities associated with concomitant HIV infection.Citation[4] Diabetic rats exhibit increased leukocyte entrapment due to alterations of leukocyte properties and microvasculature changes in diabetic retinopathy, It is speculated that leukocytes latently infected with CMV can become entrapped in the retina.Citation[5]

CMV retinitis occurs in patients with diabetes mellitus, despite immunocompetence, if the virus can overcome the localized tissue immune barrier, as in case reports following intravitreal triamcinolone.Citation[5–9] Loss of T-cell-mediated immune control or changes in the differentiation or activation state of cells harboring latent CMV can result in reactivation of latent virus and production of viral progeny.Citation[10] High doses of regional corticosteroid may exhibit a localized effect by lowering the overall (CD4+ and CD8+) lymphocyte count. Two cases of unilateral CMV retinitis in immunocompetent diabetic males who had not received regional or systemic corticosteroids have been reported; both resolved without treatment.Citation[11]

Retinal involvement from CMV infection has also been reported in immunocompetent adults without diabetes. Two forms of self-limited retinopathy have been described: unilateral cotton wool spots and persistent pinpoint chorioretinitis with irregular sheathing of retinal venules.Citation[12],Citation[13] On the other end of the spectrum, unrecognized CMV retinitis treated with high-dose systemic corticosteroid therapy resulted in severe, bilateral necrotizing retinitis and bilateral retinal detachment in 1 adult female.Citation[14]

Cytomegalovirus infection can elevate blood pressure in mice and stimulate the overexpression of renin and angiotensin II (Ang II).Citation[15] Approximately one-third of immunocompetent adults with CMV-associated thrombosis have acquired or inherited predisposition for thrombosis, the most common inherited being factor V Leiden mutation.Citation[16] Systemic hypertension (HT) was reported in 1 patient, case 5, which was associated with CRVO with a positive history of IVTA (). Our case 1 is the first case reported without IVTA developed CMV retinitis, but the patient had HT associated with factor V Leiden mutation.

Table 1. Summary of case reports on CMV retinitis in immunocompentent individuals.

Induction and maintenance therapy with intravenous ganciclovir, intravenous foscarnet, intravenous cidofovir, or oral valganciclovir is efficacious in inducing remission of cytomegalovirus retinitis. If recovery of immune function is not possible, indefinite treatment is needed.Citation[17] However, long-term treatment and high-dose intravenous ganciclovir have caused side effects; related bone marrow suppression and neutropenia, carcinogenesis, teratogenesis, and azospermia have been reported.Citation[17],Citation[18] We believe the benefit of avoiding sight-threatening progression of retinitis outweighs the potential risks of long-term therapy in the cases we report.

Our report aims at raising awareness that patients previously exposed to CMV with comorbid diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or hypercoaguable states may be at higher risk for the development of CMV retinitis. This is particularly relevant following local or systemic immunosuppressant therapy, particularly regional or long-acting corticosteroid preparations.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Carlstrom G. Virologic studies on cytomegalic inclusion disease. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1965;54:17–23

- Krech U. Complement-fixing antibodies against cytomegalovirus in different parts of the world. Bull World Health Organ. 1973;49:103–106

- Lopez-Contreras J, Ris J, Domingo P, et al. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent adult successfully treated with ganciclovir. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:523–525

- Glasgow BJ, Weisberger AK. A quantitative and cartographic study of retinal microvasculopathy in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994; 118:46–56

- Miyamoto K, Hiroshiba N, Tsujikawa A, et al. In vivo demonstration of increased leukocyte entrapment in retinal microcirculation of diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2190–2194

- Saidel MA, Berreen J, Margolis TP. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after intravitreous triamcinolone in an immunocompetent patient. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1141–1143

- Vertes D, Snyers B, De Potter P. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after low-dose intravitreous triamcinolone acetonide in an immunocompetent patient: a warning for the widespread use of intravitreous corticosteroids. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:595–597

- Delyfer MN, Rougier MB, Hubschman JP, et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis following intravitreal injection of triamcinolone: report of two cases. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:681–683

- Sekiryu T, Iida T, Kaneko H, et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide in an immunocompetent patient. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2008;52:414–416

- Britt W. Manifestations of human cytomegalovirus infection: proposed mechanisms of acute and chronic disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:417–470

- Yoshinaga W, Mizushima Y, Abematsu N, et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompetent patients. Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;112:684–687

- England AC, Miller SA, Maki DG. Ocular findings of acute cytomegalovirus infection in an immunologically competent adult. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:94–95

- Chawla HB, Ford MJ, Munro JF, et al. Ocular involvement in cytomegalovirus infection in a previously healthy adult. BMJ. 1976;2:281–282

- Stewart MW, Bolling JP, Mendez JC. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in an immunocompetent patient. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:572–574

- Cheng J, Ke Q, Jin Z, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection causes an increase of arterial blood pressure. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000427

- Atzmony L, Grosfeld A, Saar N, et al. Inherited and acquired predispositions for thrombosis in immunocompetent patients with cytomegalovirus-associated thrombosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:2–5

- Henderly DE, Freeman WR, Causey DM, Rao NA. Cytomegalovirus retinitis and response to therapy with ganciclovir. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:425–434

- Lowance D, Neumayer HH, Legendre CM, et al. Valacyclovir for the prevention of cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation. International Valacyclovir Cytomegalovirus Prophylaxis Transplantation Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1462–1470

- Marshall BC, Koch WC. Antivirals for cytomegalovirus infection in neonates and infants: focus on pharmacokinetics, formulations, dosing, and adverse events. Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11:309–321

- Park YS, Byeon SH. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after intravitreous triamcinolone injection in a patient with central retinal vein occlusion. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2008;22:143–144