Abstract

Purpose: To report 2 cases of refractory idiopathic scleritis treated with rituximab.

Design: Interventional case series.

Methods and Results: Case 1: A 54-year-old woman, presented with anterior idiopathic scleritis in her right eye. Treatment with systemic steroids was not effective. Intravenous cyclophosphamide was discontinued after an adverse event. Case 2: A 43-year-old woman presented with idiopathic posterior scleritis in her left eye. Initial treatment with steroids was ineffective. In both cases, long-lasting remission without further relapses was achieved after 4 weekly doses (375 mg/m2) of rituximab.

Conclusion: Rituximab was found to be an effective treatment for refractory idiopathic anterior and posterior scleritis.

Scleritis is a potentially sight-threatening eye disease, which often becomes a therapeutic challenge. Biological drugs are a promising option in the management of autoimmune diseases and they are increasingly being used in inflammatory eye diseases.Citation[1],Citation[2] Rituximab is a B-cell-depleting monoclonal antibody employed in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and granulomatosis with polyangeitis (GPA). Rituximab has proven to be successful in the resolution of systemic autoimmune diseases presenting with scleritis.Citation[3–7] Its action results in an increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections.Citation[8] More frequently, rituximab is associated with infusion reactions.Citation[9] We report 2 cases of refractory idiopathic scleritis, which subsided with a single course of rituximab.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

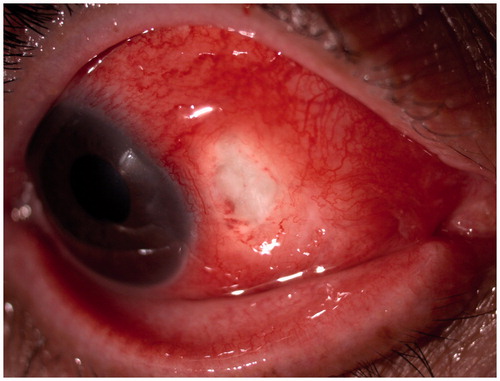

A healthy 54-year-old woman presented with severe pain and redness in the right eye, which was not improving with ibuprofen 600 mg 3 times a day. Anterior segment examination showed nasally an area of thinned sclera associated with congested scleral vessels and nodules (), revealing a necrotizing anterior scleritis. Physical examination was otherwise normal. Systemic workup was negative for syphilis, tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes simplex type I and II (HSV I & II), and hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV). Furthermore, conjunctival scraping ruled out bacterial, herpes, fungal, and mycobacterial infection.

An extensive workup for autoimmune diseases was negative for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA), anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, anti-Sm, anti-RNP 70kD, anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP), and HLA B27. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated (53 mm/h) but C reactive protein (CRP) was within normal limits. Further investigations were normal, including blood cell counts, serum biochemistry, urine analysis, levels of complement (C3 and C4), immunoglobulins (IgA, IgM, IgG), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), factor B, and rheumatoid factor (RF); chest x-ray showed no abnormalities.

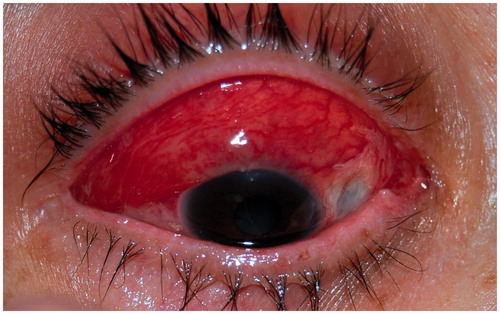

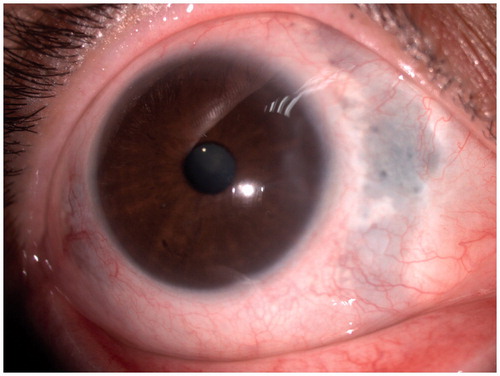

She received 3 intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone (MP) (15 mg/kg/day) and showed great improvement. Oral MP was then started at 1 mg/kg/day and her condition worsened. The pain intensified and nodules increased in size (). MP was then increased to 1.5 mg/kg/day, resulting in partial improvement. A month after diagnosis, she was started on intravenous cyclophosphamide. She underwent two 500-mg intravenous infusions separated by 14 days, after which MP was progressively reduced to 40 mg/day (0.67 mg/kg/day). No changes were noted in her eye condition. Three days after the second cyclophosphamide infusion she had a breakout of herpes zoster, after which she refused to continue with the immunosuppressant drug. Two months after the first visit, a course of 4 weekly infusions of rituximab (at 375 mg/m2) was administered, resulting in a rapid and complete response (). At the end of this course, MP dose could be reduced from 40 to 12 mg/day, and it was thereafter tapered at a rate of 2 mg per week until withdrawal 5 months after diagnosis. No relapse was noted during tapering. During a 15-month follow-up, no side effects have been noted and she has remained quiescent without any treatment.

Case 2

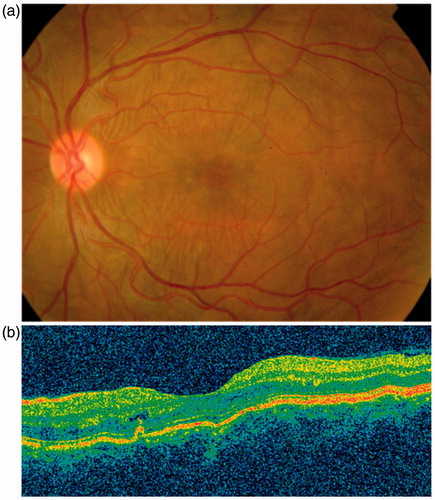

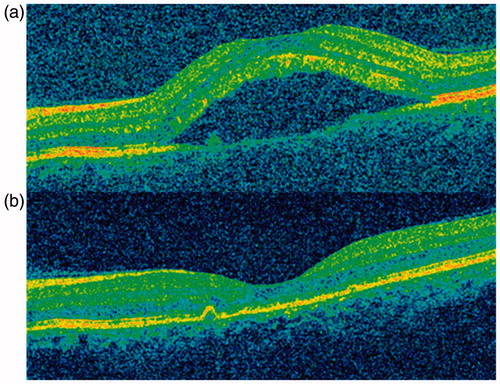

A healthy 43-year-old female presented with redness, severe pain, and blurred vision in her left eye for 1 day. Anterior segment disclosed temporal conjunctival hyperemia. Funduscopy and optical coherence tomography revealed subretinal folds (). A thickening of the posterior layers of the eye was found on B-scan ultrasonography and CT scan. A diagnosis of posterior scleritis was made.

Physical examination was normal. Systemic workup was negative for syphilis, tuberculosis, HIV, HSV I & II, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, HBV, and HCV. A workup for autoimmune diseases was negative for ANA, anti-native DNA, ANCA, anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, anti-Sm, anti-RNP 70kD, anti-CCP and HLA B27. ESR (38 mm/h) and CRP (1.2 mg/dL) were elevated. Further investigations were normal, including full blood count, uric acid, liver and renal function tests, urine analysis, levels of C3 and C4, IgA, IgM, IgG, ACE, factor B, RF, and chest x-ray.

Oral prednisone was started at 1 mg/kg/day but her visual acuity (VA) decreased and subretinal fluid appeared (). Three daily pulses of MP (15 mg/kg/day) were then given and her condition did not change. Complete resolution of scleritis occurred () after 4 infusions of rituximab (375 mg/m2/week). The patient recovered her VA and subretinal fluid disappeared. During a 20-month follow-up no further exacerbations appeared without any concomitant use of steroids.

DISCUSSION

Scleritis is a serious inflammatory eye disease that may result in permanent loss of vision, and therefore it is mandatory to rule out any medical condition for a correct therapeutic approach. Approximately half of the patients have no identifiable cause, but different studies have reported that 40–50% have an underlying infectious or rheumatic disease.Citation[10] The first step is the exclusion of an infectious etiology, after which steroid therapy is initiated, and if swelling progresses immunosuppressants are added. However, there are refractory cases or intolerable adverse events in which biological agents have been raised.

Rituximab is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD20, a surface marker expressed in pre-B and mature B lymphocytes. Rituximab results in a selective depletion of CD20+ B cells lasting up to 6–12 months.Citation[11] The cellular infiltrate in idiopathic necrotizing scleritis is primarily composed of macrophages (CD68) and, to a lesser extent, of T lymphocytes (CD3) and B lymphocytes (CD20).Citation[12] B cells are considered to play a critical role in autoimmunity, serving not only as a source of autoantibodies but also as antigen-presenting cells, and releasing chemokines that assist the activation of T cells.Citation[13],Citation[14] In this regard, typical T-cell-driven diseases, such as RA, benefit from treatment with rituximab.Citation[15] B-cell depletion with rituximab has been found beneficial in additional autoimmune conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, GPA, and primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS).Citation[9] Interestingly, in patients with RA, GPA, and pSS complicated with scleritis, the administration of rituximab, either as monotherapy or in combination with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents, has specifically shown a favorable outcome of the eye involvement.Citation[3–7] In these patients, rituximab has been administered using either the lymphoma dose regime (consisting of 4 weekly infusions of 375 mg/m2) or the RA approach (2 infusions of 1 g separated by 14 days). Irrespective of its particular cause, scleritis pathogenesis involves local vasculitis. For this reason we decided to adopt the lymphoma dose regime of rituximab administration, which at the time was most frequently employed in patients with GPA. However, the information available indicates that both dose regimes could be equal in efficacy.

In brief, Ahmadi-Simab and colleagues described remission of refractory scleritis in a patient with pSS, using 4 weekly infusions of 375 mg/m2 rituximab. Remission was maintained thereafter with 6 months of mycophenolate mofetil treatment.Citation[3] Two case reports showed a similar benefit of rituximab (two 1-g infusions separated by 14 days) in RA-associated scleritis.Citation[4],Citation[5] One of these patients was also taking oral methotrexate, and both showed remission of their condition lasting more than 6 months.Citation[5] With the latter regime, a favorable response was obtained in 2 patients with GPA-associated scleritis. In one of these cases, rituximab was administered simultaneously with cyclophosphamide and the other with MP. In none of theses cases have new exacerbations or adverse effects been observed.Citation[6],Citation[7] Recently, Kurz and colleagues have found a good response to rituximab in 2 cases of refractory scleritis and 2 with noninfectious orbital inflammation using either of the mentioned regimes of administration. They also underscored the lack of adverse effects in these patients.Citation[16]

Unfortunately, current experience with rituximab and other biologics in localized inflammatory diseases such as scleritis is still limited and these drugs remain a late therapeutic option. In our first patient, rituximab was administered as the second stage of immunosuppressant therapy after discontinuation of cyclophosphamide. In the second patient, we decided against cyclophosphamide because of the childbearing age of the patient, and rituximab was selected instead.

Available data show that rituximab has a fair safety profile. Moreover, its efficacy in monotherapy could prevent the usage of potentially toxic immunosuppressant drugs and help to withdraw corticosteroids earlier, avoiding their frequently observed side effects. Infusion reactions are the most common of reported adverse effects, and premedication with methylprednisolone, dexchlorpheniramine, and acetaminophen at each infusion can prevent or attenuate these complications. Of more concern are rare but potentially life-threatening infections associated with the depletion of B cells. These include progressive leukoencephalopathy due to reactivation of JC virus and fulminant hepatitis following HBV reactivation. Prior to rituximab initiation, different tests should be performed to evaluate risk at developing opportunistic infections. Patients with previous exposure to HBV should receive antiviral therapy during rituximab therapy. The convenience of adding other prophylactic regimes should be individually assessed. Routinely, we give cotrimoxazol for a minimum of 6 months to patients receiving rituximab. Viral load should be checked periodically in HIV or HCV carriers.Citation[8],Citation[17] We did not observe any side effects during follow-up, and both patients showed a long-lasting remission without further relapses to date.

Our case reports provide further evidence of the benefit of rituximab in the management of idiopathic scleritis. We suggest that this therapy might be considered earlier in the course of severe scleritis, since it appears to yield a prompt and sustained remission, with a good tolerability. However, future studies with more patients are warranted to better assess efficacy, dosing regime, and safety.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Michalova K, Lim L. Biologic agents in the management of inflammatory eye diseases. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8:339–347

- Lim L, Suhler EB, Smith JR. Biologic therapies for inflammatory eye disease. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:365–374

- Ahmadi-Simab K, Lamprecht P, Nölle B, et al. Successful treatment of refractory anterior scleritis in primary Sjogren's syndrome with rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1087–1088

- Chauhan S, Kamal A, Thompson RN, et al. Rituximab for treatment of scleritis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:984–985

- Iaccheri B, Androudi S, Bocci EB, et al. Rituximab treatment for persistent scleritis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:223–225

- Cheung CM, Murray PI, Savage CO. Successful treatment of Wegener's granulomatosis associated scleritis with rituximab. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1542

- Onal S, Kazokoglu H, Koc A, et al. Rituximab for remission induction in a patient with relapsing necrotizing scleritis associated with limited Wegener's granulomatosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008;16:230–232

- Gea-Banacloche JC. Rituximab-associated infections. Semin Hematol. 2010;47:187–198

- Miserocchi E, Pontikaki I, Modorati G, et al. Anti-CD 20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) treatment for inflammatory ocular diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;11:35–39

- Akpek EK, Thome JE, Qazi FA, et al. Evaluation of patients with scleritis for systemic disease. Ophthalmology 2004;111:501–506

- Shaw T, Quan J, Totoritis MC. B cell therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: the rituximab (anti CD20) experience. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:55–59

- Usui Y, Parikh J, Goto H, et al. Immunopathology of necrotising scleritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:417–419

- Dörner T, Isenberg D, Jayne D, et al. Current status on B cell depletion therapy in autoimmune diseases other than rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;9:82–89

- Piccio L, Naismith R, Trinkaus K, et al. Changes in B- and T-lymphocyte and chemokine levels with rituximab treatment in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:707–714

- Takemura S, Klimiuk P, Braun A, et al. T cell activation in rheumatoid synovium is B cell dependent. J Immunol. 2001;167:4710–4718

- Kurz PA, Suhler EB, Choi D, et al. Rituximab for treatment of ocular inflammatory disease: a series of four cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:546–548

- Kelesidis T, Daikos G, Boumpas D, et al. Does rituximab increase the incidence of infectious complications? A narrative review. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e2–e16