Sarcoidosis is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology characterized by noncaseating granulomas.Citation1 It can affect many organs and tissues, including lungs, lymph nodes, eye, skin, central and peripheral nervous system, muscle, liver, spleen, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. Although sarcoidosis predominately involves the lungs, ocular manifestations are also a prominent feature of the disease. Approximately one-fifth of the patients seek medical attention because of ocular complaints, which is the second most frequent clinical manifestation, exceeded only by pulmonary involvement.Citation2

Ocular findings have been documented in 25–50% of patients with sarcoidosis. Bilateral granulomatous uveitis is the most well-known presentation.Citation3 However, ocular manifestations of sarcoidosis may comprise a variety of clinical findings, including anterior, intermediate, or posterior uveitis, optic neuropathy, adnexal and orbital disease, scleral involvement, glaucoma, and cataracts.Citation4 The lacrimal gland is the most common adnexal site affected,Citation5 which can occur prior to other manifestations of the disease,Citation6 and may lead to subsequent sicca syndrome. Scleral involvement is infrequently reported in the literature, particularly in the absence of other ocular involvement. The few cases described thus far presented as nodular scleritis rather than painless mass lesions.Citation7–9 We herein present a case of a scleral granuloma presenting without any obvious signs of scleritis, which was proven to be due to sarcoidosis.

Case Report

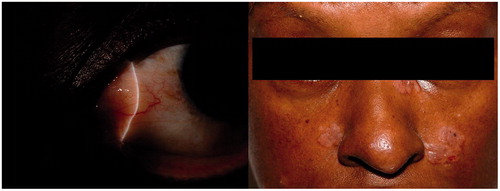

A 58-year-old black female was referred for further evaluation of a painless “conjunctival growth” in the left eye. The patient's visual acuity was 20/20 bilaterally. Slit-lamp examination demonstrated an elevated lesion measuring about 6 × 7 mm, within the interpalpebral fissure, located nasally (). It was covered with intact, seemingly normal conjunctiva. The lesion was immobile when touched with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator beneath the conjunctival epithelium. External examination was significant for several foci of slightly hypopigmented, indurated, elevated plaques on the left side of her nose and on both cheeks (). The patient's primary care physician had made a presumptive diagnosis of ringworm for which topical medications were used with no improvement.

Figure 1. (Left) Slit-lamp appearance of the subconjunctival elevated mass lesion covered with seemingly normal epithelium localized to the medial rectus muscle area in a patient with scleral sarcoid nodule. (Right) Facial appearance of the same patient demonstrating slightly hypopigmented, purplish, indurated, elevated plaques on the left side of her nose and on both cheeks.

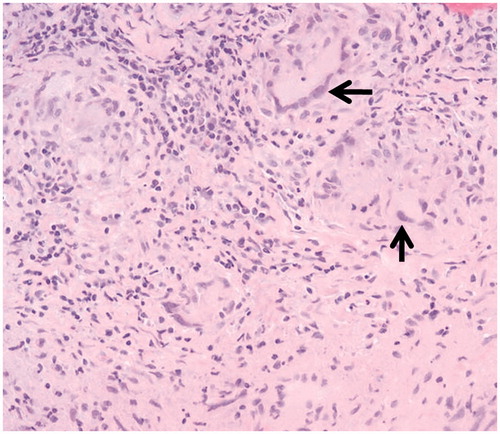

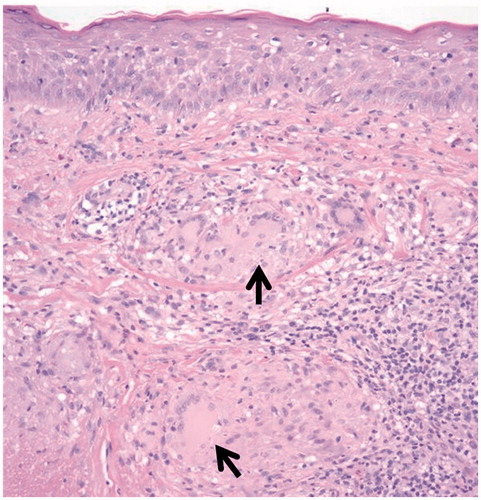

The patient underwent a biopsy of the lesion for diagnostic purposes. Following peritomy of the nasal conjunctiva, the mass lesion was visualized stemming off of the sclera and invading the insertion of the medial rectus muscle. The lesion was excised partially so as not to disturb the muscle and submitted in one piece. Light microscopic examination of the specimen revealed chronic inflammation and fibrosis in the subconjunctival substantia propria, while the actual scleral lesion was composed of diffuse noncaseating granulomatous inflammation with giant cells (). Special stains for acid-fast organisms and fungi were negative. In addition, the patient was referred to the dermatology clinic for biopsy of the facial skin lesions. The light microscopic examination of the dermatological specimen demonstrated that epidermis was unremarkable, while the dermis contained epithelioid histiocytes arranged into well-formed granulomas, with no organisms identified (). An extensive systemic evaluation did not demonstrate other organ involvement. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis with sclera and skin involvement was confirmed. The skin lesions were identified as lupus pernio. Topical steroid cream was recommended by dermatology clinic for affected facial lesions. Topical cyclosporine eyedrops 1% were prescribed for the scleral lesion. Systemic treatment with 40 mg of oral prednisone daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was also initiated. Due to no improvement in cutaneous or scleral findings after 4 months, triamcinolone acetonide injections were utilized for the facial lesions. Systemic methotrexate is currently being considered as an alternative treatment.

Discussion

The key clinical feature in this case is the presence of the facial skin lesions in addition to the finding of scleral nodule. The gold standard for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is histopathological confirmation demonstrating noncaseating granulomas, and exclusion of other diseases that cause granulomatous lesions, such as tuberculosis. Although the eye is a frequent target for sarcoidosis, scleral granulomas, as in this case, in the absence of clinical signs of scleritis have never been reported in the literature.

Although the most common cutaneous involvement from sarcoid is papular lesions, various other specific skin lesions, including hypopigmented macules, plaques, ulcerative lesions, ichthyosiform cutaneous changes, erythrodermic sarcoid, and subcutaneous nodules, have also been described. Lupus pernio is likely the most well-recognized chronic skin lesion of sarcoidosis.Citation10 It occurs most commonly in black women and presents as indurated, red-brown to purple plaques on the nose, lips, cheeks, and ears.Citation11 Lupus pernio has a chronic course that often requires prolonged treatment.Citation12 Importantly, a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis should always provoke additional investigation for systemic involvement.Citation10

Treatment of ocular sarcoidosis is tailored to the extent of involvement. A detailed literature search using PubMed did not demonstrate any reports specific to scleral nodules. Topical cylosporine has been shown to be an effective treatment for conjunctival involvement.Citation13 Topical, periocular, and intravitreal corticosteroids are often employed in the management of intraocular involvement. The use of systemic corticosteroids may be helpful to reduce ocular inflammation. However, side effects are considerable with chronic treatment. There have been reports of favorable outcomes with oral cyclosporine therapy in vision-threatening sarcoid-associated uveitis.Citation14 Additional immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate, and leflunomide, have also been employed as steroid-sparing treatments in the management of ocular sarcoidosis. Biologics targeted toward tumor necrosis factor, such as infliximab (chimeric monoclonal antibody) and adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), have also been reported effective in patients with persistent disease or intolerant of other immunomodulating therapy.Citation15

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Ianuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153–2165

- Obenauf CD, Shaw HE, Sydnor CF, Klintworth GK. Sarcoidosis and its ophthalmic manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86:648–655

- Crick RP, Hoyle C, Smellie H. The eyes in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1961;45:461–481

- Ohara K, Judson MA, Baughman RP. Clinical aspects of ocular sarcoidosis. In: Drent M, Costabel U, eds. Sarcoidosis. Wakefield, UK: Charlesworth Group;2005:188–209

- Prabhakaran VC, Saeed P, Esmaeli B, et al. Orbital and adnexal sarcoidosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1657–1662

- Yanardag H, Pamuk ON. Lacrimal gland involvement in sarcoidosis: the clinical features of 9 patients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:388–391

- Saito W, Kotake S, Ohno S. A patient with sarcoidosis diagnosed by a biopsy of scleral nodules. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:374–376

- Qazi FA, Thorne JE, Jabs DA. Scleral nodule associated with sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:752–754

- Babu K, Kini R, Mehta R. Scleral nodule and bilateral disc edema as a presenting manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:158–161

- Mana J, Marcoval J, Graells J, Salazr A. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882–888

- Marcoval J, Mana J, Rubio M. Specific cutaneous lesions in patients with systemic sarcoidosis: relationshop to severity and chronicity of disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:739–744

- James GD. Lupus pernio. Lupus. 1992;1:129–131

- Akpek EK, IIhan-Sarac O, Green R. Topical cyclosporin in the treatment of chronic sarcoidosis of the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003; 121:1333–1335

- Baughman, RP, Lower EE. Steroid-sparing alternative treatments for sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 1997;18:853–864

- Baughman RP, Lower EE, Kaufman AH. Ocular sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:452–462