Abstract

Diphtheroids were generally regarded as nonpathogenic contaminants, but recent clinical studies have emphasized that they may cause serious systemic and ocular disease mostly in patients with underlying medical conditions. In this study we present a case report of acute onset endogenous endophthalmitis associated with heavy growth of diphtheroids on the culture of anterior chamber fluid sample in a 46-year-old man with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. He did well after appropriate treatment and a functional vision was restored. This case highlights the importance of proper management for the outcomes of patients with endogenous endophthalmitis. It is also significant to be cautious about a life-threatening medical status in a patient with such presentation.

Introduction

Endogenous endophthalmitis is a sight-threatening serious disease caused by access of microorganisms from a primary site of infection to the intraocular spaces through the bloodstream. This infection is usually associated with underlying chronic illnesses, various primary infectious diseases, immunosuppressive conditions, and invasive procedures.Citation1 Gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria, and fungi are the frequently reported pathogens responsible for most cases of endogenous endophthalmitis.Citation2 It is an infrequent condition compared to exogenous endophthalmitis and generally associated with poor prognosis.Citation3

Diphtheroids are gram-positive pleomorphic bacilli in the family of Coryneform bacteria. These organisms are present in the human flora and generally regarded as nonpathogenic contaminants but may cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised persons.Citation4 In this study, we present a case of an endogenous endophthalmitis caused by diphtheroids in a patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

A 46-year-old man was admitted with a complaint of decreased vision and redness in his right eye for 3 days. He had no history of ocular trauma or intraocular surgery. He had received a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus 10 years before and had been receiving oral anti-diabetic medication. He did not have a regular follow-up for glycemic control so he was unaware of his blood glucose level.

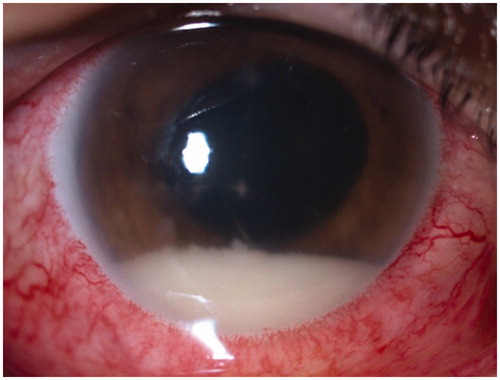

His ophthalmic examination revealed visual acuity of counting fingers in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. Intraocular pressure was 30 mmHg in the right and 16 mmHg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed injected conjunctiva, keratic precipitates on the corneal endothelium, 4+ anterior chamber cells with hypopyon, and a dense fibrin plaque in the pupillary space (). Posterior segment examination revealed only a poor retinal red reflex because the inflammation precluded detailed fundus evaluation in the right eye. Anterior segment examination findings were normal in the left eye. Hard exudates and retinal microhemorrhages were noted in the posterior pole of the left eye that were consistent with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. B-scan ultrasonography of the right eye revealed normal posterior segment findings without any focus of high reflectivity within the vitreous.

Figure 1. Anterior segment photography of the patient at presentation, showing injected conjunctiva and hypopyon.

The patient was hospitalized and endogenous endophthalmitis was considered the most likely diagnosis. Nevertheless, since the inflammation was localized mainly to the anterior chamber and B-scan ultrasonography did not show a marked vitreous involvement, the differential diagnosis included uveitis with hypopyon. As initial ophthalmic procedure an anterior chamber tap from the right eye was performed under the microscope in the operating room, the fluid sample was analyzed for bacteriologic and cytologic diagnosis, and subconjunctival gentamicin-dexametasone was administered. The patient was prescribed topical fortified antibiotic (vancomycin 50 mg/mL and gentamicin 15 mg/mL) and topical steroid (prednisolone acetate) eyedrops hourly. The treatment also included cycloplegic and antiglaucomatous (topical timolol–dorzolamide combination) medications. Meanwhile, the patient underwent an extensive systemic workup. Investigations included full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), blood chemistry and serology, urine analysis, and blood and urine cultures. He underwent a complete physical examination and abdominal ultrasonography, which were unremarkable. Laboratory data were significant for white blood cell count (14,000/μL), ESR (69 mm/h), and C-reactive protein (13.2 mg/L), consistent with a systemic infection. But the most remarkable data were the blood glucose level of 528 mg/dL and HbA1c level of 18.4%, showing an uncontrolled diabetic state. The remainder of the laboratory results were normal. Oral anti-diabetic treatment was switched to insulin injection by the endocrinology department. Considering the recommendations of infectious disease consultants, a sulbactam-ampicilin and ciprofloxacin combination was administered intravenously for the source of a possible bacterial infection.

Ophthalmologic examination findings did not differ in the first 48 h of hospitalization. Blood and urine cultures were negative. On the culture of the anterior chamber fluid sample, heavy growth of diphtheroids was detected and the sample was found rich in polymorphonuclear leucocytes in the cytologic evaluation. So the patient underwent vitreous tap and intravitreal vancomycin (1 mg/0.1 mL) and amikacin (0.4 mg/0.1 mL) injection. The patient did well and 3 days after the injection his visual acuity gradually improved and reached 20/250, aqueous fibrin and hypopyon disappeared, and fundus details became visible. The causative organism could not be obtained from the culture of vitreous tap. Since the inflammation regressed and the glycemic control was managed, the patient was discharged after completing a 10-day course of intravenous antibiotic treatment with a tapering regimen of topical fortified antibiotics and steroid eyedrops. One month after discharge, the best-corrected visual acuity was 20/50 and intraocular pressure was 12 mmHg in his right eye without antiglaucomatous treatment. He had no aqueous or vitreous inflammation. In this visit fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) and optic coherence tomography (OCT) were performed. In FFA, mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy findings were observed in both eyes; in addition, hyperfluorescence from optic disc and choroidal vasculature was remarkable in the right eye and was thought to occur secondary to the previous intraocular inflammation. Macular OCT findings were normal in both eyes. Three months later, his best-corrected visual acuity was 20/50, intraocular pressure was normal, and no ocular inflammation was noted in his right eye.

It is important to be cautious about endogenous endophthalmitis, especially in patients with predisposing medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and malignancies.Citation5 Generally, ophthalmologic examination findings typically include ciliary injection with aqueous and/or vitreous inflammation that is significant to determine. But, just as in our patient, if the inflammation occurs predominantly in the anterior segment of the eye, it can easily be misdiagnosed as noninfectious inflammation. At the time of admission uveitis with hypopyon was among our differential diagnoses. But the investigations included intraocular sampling for culture and treatment included fortified antibiotic eyedrops, since endogenous endophthalmitis was the most likely diagnosis considering the patient's uncontrolled diabetes status. Likewise, despite intensive topical steroid treatment, no clinical change was noted in 48 h so we excluded anterior uveitis completely. In this period we preferred to delay intravitreal antibiotic injection until we got a clue about causative organism because such clinical presentations in diabetic patients may be associated with fungi.Citation5

Blood culture is said to be the most reliable way of establishing the diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis, but nearly one-quarter of blood cultures were negative in a large case series.Citation1 It is also possible to isolate the causative organism from extraocular cultures, such as urine, lung, liver, and so on, according to the underlying systemic pathology of the patient.Citation2,Citation3 Despite extensive systemic investigations, it is not always possible to identify the source of infection, as in our patient. Although intraocular culture is more reliable in exogenous endophthalmitis than in endogenous endophthalmitis, Greenwald et al. advocated anterior chamber sampling for most patients, particularly those with predominantly anterior segment involvement, just as in our patient.Citation6

Diphtheroids were previously regarded as nonpathogenic organisms. When they grew in the culture they were usually considered to be a contamination of normal flora.Citation7 Nowadays we know that they can cause systemic diseases, especially in immunocompromised persons. They are also reported as the causative organisms of ocular surface infections and exogenous endophthalmitis.Citation8,Citation9 To the best of our knowledge, our patient is the second case of endogenous endophthalmitis caused by diphtheroid bacillus in the literature. The other case was a patient with bilateral subretinal abcess, who has been using systemic steroids owing to minimal change nephrotic syndrome.Citation7

Unlike for exogenous endophthalmitis, there has not been a standard protocol for endogenous endophthalmitis. Therapy is driven mostly according to the patient's clinical features on presentation, the patient's underlying medical condition, and the experiences of the clinicians about this situation. Generally, systemic antibiotic treatment is considered the cornerstone therapy for endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis.Citation10 Treatment also includes topical and subconjunctival antibiotics. But all of these medications may be inadequate to reach therapeutic levels within the intraocular spaces, as in our patient. Intravitreal administration of antibiotics may provide rapid therapeutic levels within the eye. Pars plana vitrectomy is another treatment modality but the role and timing of this procedure remains controversial in patients with endogenous endophthalmitis.Citation2

In conclusion, diphtheroids should not be regarded as contaminants when isolated from cultures of patients with underlying chronic illnesses. Thus, they should be kept in mind as possible responsible organisms for endogenous endophthalmitis in these patients. It is also important to be aware that such conditions may serve as an important indicator of a severe life-threatening medical status.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, Stanford MR. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:403–423

- Lee S, Um T, Joe SG, et al. Changes in the clinical features and prognostic factors of endogenous endophthalmitis: fifteen years of clinical experience in Korea. Retina. 2012;32:977–984

- Harris EW, D'Amico DJ, Bhisitkul R, et al. Bacterial subretinal abscess: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:778–785

- Lipsky BA, Goldberger AC, Tompkins LS, Plorde JJ. Infections caused by nondiphtheria Corynebacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4:1220–1235

- Zhang H, Liu Z. Endogenous endophthalmitis: a 10-year review of culture-positive cases in northern China. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:133–138

- Greenwald MJ, Wohl LG, Sell CH. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis: a contemporary reappraisal. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986;31:81–101

- Uysal Y, Bağkesen H, Erdem Ü, et al. Bilateral subretinal abscess due to diphtheroid rod in patient with minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Ret-Vit. 2006;14:141–144

- Rubinfeld RS, Cohen EJ, Arentsen JJ, Laibson PR. Diphtheroids as ocular pathogens. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108:251–254

- McManaway JW, Weinberg RS, Coudron PE. Coryneform endophthalmitis: two case reports. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:942–944

- Pride P, Nutaitis M, L Charity P. Endophthalmitis: an unusual presentation of bacteremia. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345:70–71