Abstract

Purpose: The subretinal fibrosis and uveitis (SFU) syndrome is a rare multifocal posterior uveitis characterized by progressive subretinal fibrosis and significant visual loss.

Methods: Slit-lamp examination, dilated fundoscopy, fluorescein angiography, Spectral Domain-Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) and laboratory testing were employed.

Results: A 52-year-old male presented with bilateral (best-corrected visual acuity: 2/10) visual loss. Clinical examination revealed bilateral anterior uveitis with posterior synechiae and posterior uveitis. Medical workup revealed no pathologic findings. Treatment included 1 gr intravenous prednisone followed by oral prednisone, immunosuppresive therapy and three ranibizumab injections in the right eye with no improvement. One year later, there was significant subretinal fibrosis. In the second year follow-up, the picture was slightly worse, with persisting bilateral macular edema and fibrosis.

Conclusions: This is the first SFU syndrome report monitored with SD-OCT. This novel imaging modality can localize the lesion level, guide the therapeutic approach and may prove helpful in assessing disease prognosis.

The subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome is a rare form of multifocal posterior uveitis characterized in its early stages by multifocal choroiditis, followed by progressive subretinal fibrosis and macular scarring, resulting in significant and permanent visual loss. The syndrome was first described by Palestine et al.Citation1 in 1984, while Gass et al. described progressive subretinal fibrosis and blindness associated with multifocal granulomatous chorioretinitis.Citation2 Fundus examination reveals multiple whitish-yellow choroidal lesions in the posterior pole. These lesions fade or enlarge and coalesce to create areas of white subretinal fibrosis, a progression that occurs over weeks to months.Citation3

We present a case of this rare disease and its evolution to fibrosis and poor visual function, despite timely and intensive treatment, with the corresponding spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) findings. Regarding ophthalmic examination, the patient was followed-up with slit-lamp examination, dilated funduscopy, and fluorescein angiography. Comprehensive laboratory testing was also performed.

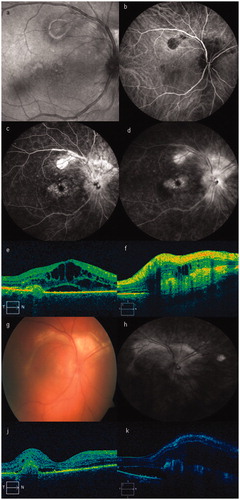

A 52-year-old male patient presented with bilateral visual loss during the previous few days. On first presentation, his best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 2/10 in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination revealed anterior chamber reaction (2 + cells), and endothelial precipitates in both eyes. The pupils were fixed because of posterior synechiae. Dilated fundus examination disclosed posterior uveitis (2 + vitreous opacity), with multiple, small, whitish-yellow retinal pigment epithelium or choroidal lesions in the posterior pole and midperiphery, and optic disc hyperemia (a). Indocyanine green angiography depicted these lesions as well (b). Fluorescein angiography revealed optic disc and macular hyperfluorescence extending into the superior temporal branch (c, d, early and late frames, respectively). SD-OCT scans (Cirrus HD-OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) of the macular area revealed macular edema and subretinal fluid (e). The SD-OCT scan of the area above the optic nerve revealed significant fibrosis with minimal intraretinal fluid (f).

Figure 1. (a) Red-free photo of the right eye on presentation. (b) Baseline visit. Indocyanine green angiography depicting the choroidal lesions. (c, d) Baseline visit. Fluorescein angiography (early and late phase), showing multiple RPE lesions, optic nerve, and macular edema. (e) Baseline visit. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan of the fovea showing macular edema and subretinal and intraretinal fluid. (f) Baseline visit. OCT scan to the upper part of the optic nerve, revealing significant fibrosis and subretinal fluid. (g) Follow-up color photo of our patient, 1 year after initial diagnosis. (h) One-year follow-up visit. Fluorescein angiography late phase, showing that the fibrotic lesions had expanded and coalesced. (j) One-year follow-up visit. OCT scan depicting macular edema and fibrosis. (k) One-year follow-up visit. OCT scan 2 years following diagnosis revealing deterioration with persisting macular edema and fibrosis.

Medical workup included physical examination, chest x-ray, and computerized tomography, which revealed no pathologic findings. Laboratory examinations revealed negative titers for antinuclear antibodies, antineurotrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, C3, C4, and anticardiolipin antibodies. Blood chemistry and blood cell counts were within normal limits, as was thyroid function. Serological investigations showed no evidence of acute infectious disease. The patient also underwent a purified protein derivative test, QuantiFERON-TB gold test, and FTA-Abs, all of which were negative.

The patient was treated with pulse intravenous prednisone of 1 g for 3 days, followed by tapering doses of prednisone orally, along with immunosuppresive therapy (CSA 200 mg/day). He also underwent 3 injections of ranibizumab in the right eye, as a rescue off-label therapy, without any functional or morphological improvement. The patient was followed up closely during the first year while he was still on immunosuppression. During this period, the lesions had expanded and merged to create areas of subretinal fibrosis of whitish color. Fundoscopy revealed an elevated ring of subretinal fibrotic tissue surrounding the optic nerve head and multifocal chorioretinitis lesions in both eyes (g). The late-phase fluorescein angiogram revealed hyperfluorescence of subretinal lesions, while SD-OCT revealed marked fibrotic subretinal tissue within the macula in both eyes (h). In the second-year follow-up, the picture was slightly worse, with persisting macular edema and fibrosis in both eyes (j, k). We elected to follow up the patient without any further treatment. During the last follow-up visit (March 2013), the patient was legally blind (BCVA: counting fingers in both eyes).

Most patients with subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome present with central visual loss and photopsias.Citation4 Visual prognosis is poor and recurrences are common. Severe visual loss is usually due to subfoveal choroidal neovascularization. Citation4 Patients have a poor prognosis due to fibrosis and atrophy involving the macula. The etiology is not known, but is believed to be a localized autoimmune reaction to the retinal pigment epithelium.

This entity presents with numerous small yellow lesions at the posterior pole and minimal signs of inflammation, which are followed within days to weeks by subretinal fluid and subretinal fibrosis. The disease is usually unilateral initially, but involves the second eye within months. Citation5 Our patient had typical findings of the progressive subretinal fibrosis syndrome described by Cantrill and FolkCitation6 and others,Citation1 which may be a severe variant of multifocal choroiditis. No systemic diseases are known to be associated with the syndrome and the underlying cause remains unknown.Citation7 Immunohistopathologic examination reveals gliosis in the retina and subretinal fibrotic tissue, as well as granulomatous lymphocytic infiltration in the choroid.Citation8, Citation9 Choroidal neovascularization is uncommon.Citation10

Gass and associates described 3 healthy subjects who developed severe visual loss only partly explained by multifocal chorioretinitis and massive subretinal fibrosis.Citation2 Histopathologic examination of 4 eyes from these patients showed widespread destruction of the outer retina and retinal pigment epithelium, massive areas of subretinal fibrous tissue proliferation, granulomatous inflammation located around degenerated and fragmented Bruch's membrane, and chronic uveitis. No infectious organisms were identified by special stains or electron microscopy.

Treatment is controversial, with some authors reporting an early beneficial effect of steroids and chemotherapy in severe cases. Gandorfer et al. propose aggressive high-dose treatment with steroids and other immunosuppresive agents, such as cyclosporine immediately following macular scarring in one eye or yellow lesions development in the second eye.Citation4 Once fibrosis has developed, steroids cannot be of any benefit. Infliximab, an anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibody, has successfully been used as a treatment in a patient with associated undifferentiated spondyloarthritis.Citation3

We decided to add ranibizumab to the treatment, as a rescue off-label therapy, despite the fact that the patient's insurance organization could not cover its cost. It was hoped that, in this very difficult to treat case, the use of ranibizumab might bring about a positive therapeutic response regarding uveitis-related macular edema or fibrosis progression. We are unaware of previous reports of this treatment in subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome and could not find any reference to it in a computerized search using MEDLINE. However, despite treatment, irreversible structural damage due to marked fibrotic subretinal tissue was detected within the macula in both eyes and visual function was poor. In our patient, intravitreal ranibizumab did not have any functional or morphological effect, as the disease progressed despite aggressive therapy with steroids, immunosuppresion, and local therapy with ranibizumab (extension of subretinal fibrosis, g, h).

Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first patient with subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome monitored with SD-OCT that has been reported in the relevant literature. This novel imaging modality can localize the lesion (retina, retinal pigment epithelium, inner choroid, or all three), and thereby guide the therapeutic approach. SD-OCT may prove helpful in monitoring the result of treatment, as well as in assessing disease prognosis.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Palestine AG, Nussenblatt RB, Parver LM, et al. Progressive subretinal fibrosis and uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984:68:667–673

- Gass JD, Margo CE, Levy MH. Progressive subretinal fibrosis and blindness in patients with multifocal granulomatous chorioretinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996:122:76–85

- Adan A, Sanmarti R, Bures A, et al. Successful treatment with infliximab in a patient with diffuse subretinal fibrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007:143:53–534

- Gandorfer A, Ulbig MW, Kampik A. Diffuse subretinal fibrosis syndrome. Retina. 2000:20:561–563

- Kaiser PK, Gragoudas ES. The subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1996:36:145–152

- Cantrill HL, Folk JC. Multifocal choroiditis associated with progressive subretinal fibrosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986:101:170–180

- Lertsumitkul S, Whitcup SM, Nussenblatt RB, et al. Subretinal fibrosis and choroidal neovascularization in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1999:237:1039–1045

- Palestine AG, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC, et al. Histopathology of the subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1985:92:838–844

- Kim MK, Chan CC, Belfort R Jr, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistopathologic features of subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987:104:15–23

- Brown J Jr, Folk JC, Reddy CV, et al. Visual prognosis of multifocal choroiditis, punctate inner choroidopathy, and the diffuse subretinal fibrosis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1996:103:1100–1105