Recovery rhetoric and reality

Recovery is the guiding principle for 21st-century mental health services throughout the Anglophone world. It is recommended in professional and clinical guidelines, and is an explicit focus of mental health policies internationally. Despite this rhetorical consensus, an emerging view from people who use mental health services is that the mental health system is commandeering the user-developed concept of recovery: incorporating the term without undergoing the fundamental transformation it requires (Mind, Citation2008).

Why might this be happening? One reason is that a recovery orientation emphasizes concepts such as agency, empowerment, strengths and purpose. Clinical training, by contrast, focuses on issues such as deficit, dysfunction, symptomatology and risk (Davidson & Roe, Citation2007). For many clinicians, it is difficult to incorporate recovery concepts into their world-view without distortion. For example, the term “choice” in relation to medication has been distorted to mean choices within a range of options defined by the prescriber, which may not include the choice of no medication.

What, if anything, needs to change if mental health services are to support personal recovery? Answering this question will require a trans-theoretical framework to map the ideas of personal recovery onto the existing constructs used by mental health professionals. A framework is intermediate between a model and a set of ideas. This is the right level: addressing the concern about a “recovery model” being the next thing that services do to the individual, whilst still being specific enough to inform working practices. A re-orientation of values and role expectations within the mental health system around this framework will then be needed, leading to new working practices which maximally support recovery.

The Personal Recovery Framework

Retta Andresen and colleagues reviewed the accounts of people who describe their own recovery journey from (and with) mental illness (Andresen, Oades, & Caputi, Citation2003). They identified recovery domains of hope, self-identity (including current and future self-image), meaning in life (including life purpose and goals), and the ability to take personal responsibility for one's own recovery. Supporting these domains will involve giving primacy to identity over illness.

What is identity? Three perspectives have evolved in the humanities. Psychologists focus on personal identity – the things that make a person unique. Being unique is the different, idiosyncratic, interesting, damaged, impassioned part of us. Personal identity involves the aspirations, dreams and preferences which sets us apart and make us a person. This individuality is the reason why there cannot be one model of recovery, why professionals should be cautious about saying (or thinking) “we do recovery”, and why the individual's views on what matters to them has to be given primacy.

Sociologists more commonly refer to social identity – the collection of group memberships that define the individual. Social identity encompasses that which joins us. It involves the development of a contextual richness to identity, which gives a sense of being like others and provides a buffer against identity challenges. Social identity is damaged when the person experiences entrapment in a low-value and stigmatised social role, such as mental health service user.

Philosophers relate identity to the existence of a persisting entity particular to a given person. Identity is that which is preserved from the previous version in time when it was modified, or it is the recognizable individual characteristics by which a person is known. Ongoing growth and transformation are central to human development, which is why the goal of returning to a premorbid state is neither attainable nor desirable.

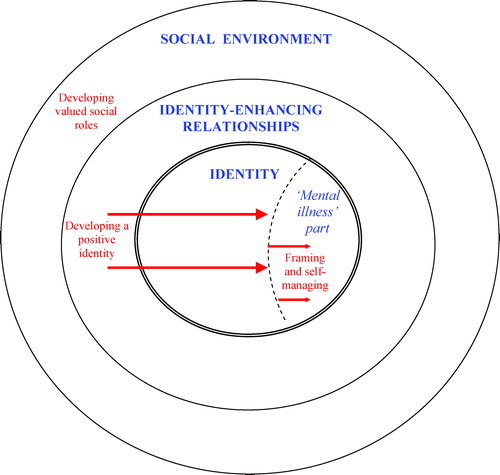

Combining these perspectives, identity comprises those persistent characteristics which make us unique and by which we are connected to the rest of the world. This definition underpins the Personal Recovery Framework (Slade, Citation2009) shown in , which illustrates the identity challenges which occur for people experiencing mental illness.

The social environment comprises the world and others in it. Identity enhancing relationships can be with the self, the mental illness or with the social environment. Figuratively, the process of recovery involves reclaiming a positive identity in two ways (shown as arrows in ): by identity-enhancing relationships and promotion of well-being which push the mental illness into being a smaller component of identity, and by framing and self-managing which pull the mental illness part. These processes take place in a social context which provides scaffolding for the development of an identity as a person in recovery.

In the Personal Recovery Framework, the individual experiences recovery through undertaking four recovery tasks. First, developing a positive identity outside of being a person with a mental illness. This process involves establishing the conditions in which it is possible to experience life as a person not an illness. Second, developing a personally satisfactory meaning to frame the experience which professionals would understand as mental illness. This involves making sense of the experience so that it can be put in a box: framed as a part of the person but not as the whole person. This meaning might be expressed as a diagnosis or a formulation, or it may have nothing to do with clinical models – a spiritual or cultural or existential crisis. The actual meaning does not matter, if it provides both a constraining frame for the experience and an impetus to move from being clinically managed to the third task of taking personal responsibility through self-management: being responsible for your own well-being, including seeking help and support from others when necessary. The final recovery task involves the acquisition of previous, modified or new valued social roles. These normally have nothing to do with mental illness.

The job of mental health professionals

The Personal Recovery Framework points to four ways in which clinicians can support an individual's recovery: fostering relationships, promoting well-being, offering treatments and improving social inclusion. Mental health services need to be oriented around these four recovery support tasks if they are to maximally support recovery.

Fostering relationships includes those with a higher being, with family and informal carers, with other people with lived experience of mental illness, and with mental health professionals. For example, exposure to people who are further along their recovery journey is profoundly hope-creating, and this is one reason to employ people with experience of mental illness in the mental health work-force. For the same reason, involvement in mutual self-help groups and intentional recovery communities (Whitley, Harris, Fallot, & Berley, Citation2008) can provide a safe space in which to create a positive personal narrative and challenge the constraints of an illness-defined identity. For professionals, the ability to connect with people during a chaotic period of their life is a recovery support when used as a springboard towards a partnership relationship, in which coaching and mentoring skills are employed by the professional to promote self-management (Borg & Kristiansen, Citation2004).

Promoting well-being involves the use of expertise on mental well-being, drawing from the science of positive psychology. For example, the Authentic Happiness theory identifies different types of good life: pleasant, engaged, meaningful and achieving (Seligman, Citation2002). The pleasant life (i.e., filled with positive emotions, symptom-free) is not the only type of good life, so supporting recovery also involves putting resources into, for example, spiritual development (for a meaningful life) or promoting activism (for an engaged life). The New Economics Foundation (www.neweconomics.org) identifies five-a-day for well-being: Connect, Be active, Take notice, Keep learning, and Give. Mental health services which are promoting well-being will focus efforts in these areas.

Offering treatments involves the use of evidence-based interventions, but oriented around recovery goals rather than treatment goals. Treatment goals are set by the clinician, and will normally relate to avoiding bad things happening, such as relapse, hospitalization, harmful risk, etc. Recovery goals are the person's dreams and aspirations. They are unique, often idiosyncratic. They are forward-looking, although they may of course involve the past. They focus on what the person actively wants, rather than what the person wants to avoid. Recovery goals are strengths-based and orientated towards reinforcing a positive identity and developing valued social roles. They can be challenging to mental health professionals, either because they seem unrealistic, inappropriate, or supporting them is outside the professional role. They sometimes involve effort by the professional, or they may have nothing to do with mental health services. They always require the service user to take personal responsibility and put in effort. Recovery goals are set by the service user. Treatment supports recovery when it is offered to the person in support of their recovery goals.

Finally, improving social inclusion is central, because hope without opportunity dies. Amartya Sen (awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1998) identified the notion of substantial freedom, meaning that even where legally codified, freedom is effectively restrained when a lack of psychological, social and financial resources make it impossible to achieve goals and live a meaningful life. The experience (and anticipation) of discrimination blights the lives of many people with mental illness. To support recovery, the focus of a clinician's role needs to enlarge beyond the level of treatment. Helping local employers to make accommodations for employees experiencing mental illness, or working with user activists to challenge discrimination, are just as much a part of the job as treating illness.

The journey of transformation

Many people who have experienced mental illness identify the positive contribution which mental health services have made to their recovery. But it is only a contribution, and professional humility is needed. Recovery involves more than receiving effective treatment: it is an active process, which can be supported but not imposed.

There is much to value in mental health services. The ability to connect with people in chaotic circumstances, the authority to carry out short-term psychiatric rescue, clinical models which provide a coherent way of making sense of experiences, and tried-and-tested interventions which help many people are some of the assets of the system. Orienting these assets towards supporting recovery may involve doing some of the same things but in different ways. Guides for mental health professionals are becoming available (e.g., rethink.org/100ways).

However, just as recovery is often described as a journey rather than an outcome, there is also a journey of change for services. New skills are needed to promote well-being, with effort targeted towards helping the individual in their struggle to develop and consolidate identity-enhancing connections and relationships. Spirituality, cultural connectedness, informal carers and intimate relationships are influential components of identity which mental health professionals can actively support. The involvement of people with lived experience of mental illness in all parts of the mental health system is an indicator that the necessity for partnership relationships is understood. The most challenging part of the journey may be shifting values. For example, there may be a trade-off between acting in the person's best interests and supporting self-management, pointing to the need for a new balance in professional ethics. More profoundly, a shift is needed so that people with mental illness are seen as part of the solution not part of the problem. To illustrate, support for positive risk-taking requires a change in societal expectations that mental health services will manage risk. People with experience of mental illness can highlight the adverse personal consequences of overly focussing on risk management, and their voice may be more powerful than professionals in shaping public expectations.

Change in values and behaviour is difficult. For people using services, this is why recovery can take a long time. For people working in services, it is just as difficult, but also just as necessary if recovery is to become a reality.

References

- Andresen, R., Oades, L., Caputi, P. (2003). The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: Towards an empirically-validated stage model. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 586–594.

- Borg, M., Kristiansen, K. (2004). Recovery-oriented professionals: Helping relationships in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 13, 493–505.

- Davidson, L., Roe, D. (2007). Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: One strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. Journal of Mental Health, 16, 459–470.

- Mind (2008). Life and times of a supermodel. The recovery paradigm for mental healthLondon: Mind.

- Seligman, M. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillmentNew York: Free Press.

- Slade, M. (2009). Personal recovery and mental illness. A guide for mental health professionalsCambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Whitley, R., Harris, M., Fallot, R.D., Berley, R.W. (2008). The active ingredients of intentional recovery communities: Focus group evaluation. Journal of Mental Health, 17, 173–182.