Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma that accounts for 1–2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [Citation1]. It is frequently seen in the elderly and is characterized by adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and constitutional symptoms [Citation2]. Despite being classified as a CD4+ T-cell malignancy, the lymph nodes usually present with a mixed picture, including an inflammatory background with polyclonal plasma cells and B immunoblasts. Another common finding in AITL is the presence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive B-cells [Citation3]. The exact role of these EBV-infected B-cells in AITL is unclear. Whether they represent EBV reactivation in the setting of a dysfunctional immune system or are involved in the pathogenesis of AITL remains to be determined.

While the AITL population is heterogeneous in nature, many cases follow an aggressive course, and fewer than 50% of patients achieve a complete response [Citation4,5]. Many chemotherapy agents and regimens including transplant have been tried, but with response rates and long-term survival rates generally less than 30% [Citation4–6]. Due to the rarity of this malignancy, published data on treatment are limited, and there is no consensus on optimal therapy.

We previously reported the case of a patient with a chemotherapy refractory EBV-positive T-cell post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) who entered a long-term remission after treatment with bexarotene. Based on the similarities between AITL and EBV-positive T-cell PTLD, we treated a patient with AITL with bexarotene and now report her outcome.

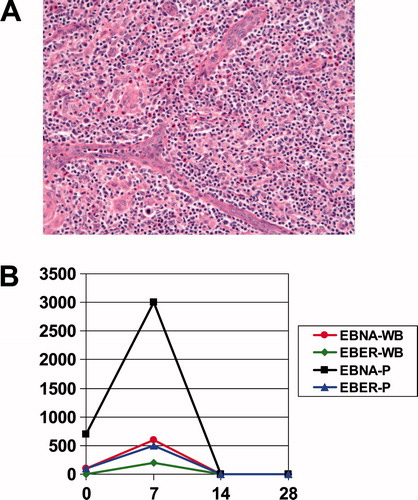

The patient is a 53-year-old white woman with a history of Hodgkin lymphoma who presented with fatigue, fever, night sweats, weight loss, and diffuse lymphadenopathy. Excisional biopsy revealed effacement of the nodal architecture by small to medium sized lymphocytes that were CD3 and CD5 positive with rare CD30 co-expression and polyclonal B-cells, consistent with AITL [(A)]. T-cell receptor polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for a clonal population. She was given the diagnosis of AITL and was treated with gemcitibine with a complete response. Two years later she developed fevers, fatigue, night sweats, and anorexia, and was found to have recurrent adenopathy with splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia: platelet count 53 000/µL and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 1395 U/L (upper limit of normal [ULN] 618). She received a single course of gemcitibine with transient response in her adenopathy, but no response in her symptoms. Within a month, she developed new diffuse pain and spinal tenderness, with worsening cytopenias requiring prednisone 40 mg daily for symptom control. Bone marrow biopsy showed 20% involvement of her cellularity by AITL. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed an elevated protein of 868 mg/dL (normal <46 mg/dL) and cytology positive for T-cell lymphoma. T-cell receptor PCR on peripheral blood was positive for a clonal T-cell population. She was treated with one course of high-dose methotrexate (3 gm/m2) with pulse dexamethasone 20 mg q.d. for 5 days, with no response in her pain, cytopenias, or constitutional symptoms. Her serum LDH was 1281 U/L, hemoglobin 9 g/dL, platelet count 43 000/µL, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 3 due to fatigue, fevers, anorexia, and weight loss. She was diagnosed with a Coombs positive hemolytic anemia and was started on prednisone 30 mg daily. Peripheral blood plasma EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was positive at 700 virions/mL [(B)]. She was initiated on bexarotene at a dose of 150 mg/m2 daily for treatment of her AITL. Within a week she noted improvements in her constitutional symptoms, with decreased fever and fatigue. At 2 weeks, her platelet count had increased to 199 000/µL, her hemoglobin to 10.6 g/dL, and her EBV qPCR had normalized. By 3 weeks, her hemoglobin was 12.5 g/dL and her LDH had decreased to 556 U/L. Her prednisone was tapered off after 1 month. At 3 months, her T-cell receptor PCR on her peripheral blood had become negative and her bexarotene dose was decreased to 150 mg b.i.d. due to elevated triglyceride levels. By 8 months, her adenopathy had resolved and her spleen was normal size. The patient has been on bexarotene for 61 months and remains in remission without adenopathy or splenomegaly. Her peripheral blood T-cell receptor PCR results vary between negative and positive and she has continued mild cytopenias, with white blood cell count (WBC) ranging from 2000 to 4000/mm3 and platelet count ranging from 100 000 to 150 000/µL. She has no other clinical or radiologic evidence of active lymphoma and is asymptomatic on a stable dose of bexarotene.

Figure 1. (A) Image from December 2001 biopsy: The nodal architecture is effaced by a polymorphic cellular infiltrate, with a spectrum of lymphoid cells (including clusters of clear cells and scattered large atypical immunoblasts), as well as eosinophils and prominent vascular elements, with frequent arborizing vessels. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×200. (B) EBV PCR on peripheral blood. Both peripheral whole blood (WB) and plasma (P) were subjected to EBV quantitative real-time PCR utilizing primer sets against EBV encoded RNA (EBER) and EBNA on days 0, 7, 14, and 28 of bexarotene (Viracor-IBT Laboratories, Lee’s Summit, MO).

AITL is a rare subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma with distinct clinical and pathologic features. It typically occurs in older adults and is characterized by features suggestive of immune system activation such as fevers, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, skin rash, and fatigue [Citation1,2]. Consistent with immune system dysregulation is the common presence of polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. AITL-involved lymph nodes reveal the presence of malignant CD4 and CD10 positive T-cells in the setting of a microenvironment of inflammatory reactive B-cells and plasma cells. EBV gene expression is commonly found within these B-cells. Whether this presence of EBV-infected B-cells represents reactivation of EBV due to immune dysregulation deriving from the AITL or whether EBV has a direct role in the pathogenesis of AITL remains to be determined [Citation3]. Nevertheless, our case demonstrates the potential use of the peripheral blood EBV qPCR assay as a tumor markerfor AITL [(B)], as the patient’s EBV titers fell to undetectable levels after day 14 on bexarotene,corresponding with the improvement in her clinicalpicture.

The optimal treatment for AITL is unclear. Various chemotherapy regimens have been tested, but complete remission rates are generally less than 50% and overall survival is only 18 months [Citation4]. Our patient presented with the additional complications of pancytopenia and poor performance status, as well as central nervous system (CNS) involvement that was refractory to conventional therapy with high-dose methotrexate. Given the limited therapeutic options available and the similarities between her case and another of our patients with EBV-positive T-cell PTLD, a decision to treat her with bexarotene was made, resulting in a sustained multi-year ongoing response [Citation7].

Her response is notable for a number of reasons. This is the first report of the activity of bexarotene in AITL. It also appears that bexarotene is able to penetrate the blood–brain barrier to treat her lymphomatous meningitis. Despite her pancytopenia and poor performance status, she clinically improved rapidly after initiating bexarotene and suffered no significant adverse events. She has now had a sustained complete response lasting for over 4 years and is currently on low-dose maintenance bexarotene alone. In our previous report of bexarotene in EBV-positive T-cell PTLD, the patient had diffuse multiorgan and CNS involvement by lymphoma that was refractory to CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) [Citation7]. He responded quickly to bexarotene and remained in a complete remission for over 2 years, until his bexarotene was discontinued for unrelated reasons, leading to relapse of his original PTLD. Despite being in remission for over 4 years while on bexarotene, our patient has occasional positive T-cell receptor PCR tests on her peripheral blood, suggesting that she continues to have AITL. Given bexarotene’s suppressive palliative effects on cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and our previous experience with EBV-positive T-cell lymphomas, it is unlikely that our patient has been or will be cured of her AITL, and she will likely need life-long maintenance bexarotene. Her prompt and lasting response to bexarotene is especially remarkable given the chemotherapy-resistant nature of her AITL.

Based on our experience reported here, bexarotene, an oral synthetic retinoid, may represent an attractive therapeutic option for AITL that has failed to respond or has relapsed after chemotherapy. Retinoid X receptors have biologic activity distinct from that of retinoic acid receptors, and act as transcription factors that regulate a number of cellular processes. Bexarotene selectively binds and activates a number of retinoid X receptors [Citation8]. The exact anti-tumor mechanism of action of bexarotene is unknown, but it has activity against a number of malignancies such as CTCL [Citation9], acute myeloid leukemia [Citation10], and breast cancer [Citation11]. Bexarotene is approved for the treatment of refractory or relapsed CTCL, where it has a reported response rate of 36% [Citation9]. While bexarotene may induce long-term remissions in CTCL, it is not felt to be curative. When weighted against other therapies, bexarotene compares favorably with conventional combination cytotoxic chemotherapy, having multiple potential cellular pathway targets, minimal organ toxicity, no immunosuppressive effects, and no need for dose adjustment for organ dysfunction. The exact mechanism of bexarotene’s action in our patient is unclear. Based on its known activity in CTCL, it may be acting through a general anti-T-cell suppressive mechanism. AITL has previously been shown to respond to other non-cytotoxic T-cell suppressive therapies such as cyclosporine and α-interferon. Finally, based on its activity in unrelated cancers such as lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and breast cancer, it may be functioning through its properties as a retinoic acid, which might affect cell differentiation or proliferation [Citation10].

With proven efficacy in other T-cell malignancies and a favorable toxicity profile, bexarotene may be a useful treatment for AITL, especially for disease that has relapsed after or is resistant to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy. Further study of bexarotene for the treatment of AITL is warranted.

Potential conflict of interest:

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at www.informahealthcare.com/lal.

References

- Rudiger T, Weisenburger DD, Anderson JR, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results from the Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma classification project. Ann Oncol 2002;13:140–149.

- Greer JP. Therapy of peripheral T/NK neoplasms. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006:331–337.

- Weiss LM, Jaffe ES, Liu XF, et al. Detection and localization of Epstein-Barr viral genomes in angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy and angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy-like lymphoma. Blood 1992;79:1789–1795.

- Steinberg AD, Seldin MF, Jaffe ES, et al. NIH conference. angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. Ann Intern Med 1988;108:575–584.

- Gisselbrecht C, Gaulard P, Lepage E, et al. Prognostic significance of T-cell phenotype in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA). Blood 1998;92:76–82.

- Kyriakou C, Canals C, Goldstone A, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in angioimmunoblastic lymphoma: complete remission at transplantation is the major determinant of outcome-Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:218–224.

- Tsai DE, Aqui NA, Vogl DT, et al. Successful treatment of T-cell post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder with the retinoid analog bexarotene. Am J Transplant 2005;5:2070–2073.

- Boehm M, Zhang M, Badea B, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of novel retinoid X receptor-selective retinoids. J Med Chem 1994;37:2930–2941.

- Duvic M, Hymes K, Hearld P, et al. Bexarotene is effective and safe for treatment of refractory advanced stage cutaneous T cell lymphoma: multinational phase II-III trial results. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2456–2471.

- Tsai DE, Luger SM, Andreadis C, et al. A phase I study of bexarotene, a retinoic X receptor agonist, in non-M3 acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:5619–5625.

- Esteva F, Glaspy J, Baidas S, et al. Multicenter phase II study of oral bexarotene for patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:999–1006.