Abstract

Introduction: Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) is a genetic disease caused by a point mutation in the TTR gene that causes the liver to produce an unstable TTR protein. The most effective treatment has been liver transplantation in order to replace the variant TTR producing liver with one that produces only wild-type TTR. ATTR amyloidosis patients’ livers are reused for liver sick patients, i.e. the Domino procedure. However, recent findings have demonstrated that ATTR amyloidosis can develop in the recipients within 7–8 years. The aim of this study was to elucidate how the genetic profile of the liver is affected by the disease, and how amyloid deposits affect target tissue. Methods: Gene expression analysis was used to unravel the genetic profiles of Swedish ATTR V30M patients and controls. Biopsies from adipose tissue and liver were examined. Results and Conclusions: ATTR amyloid patients’ gene expression profile of the main source organ, the liver, differed markedly from that of the controls, whereas the target organs’ gene expression profiles were not markedly altered in the ATTR amyloid patients compared to those of the controls. An impaired ER/protein folding pathway might suggest ER overload due to mutated TTR protein.

Introduction

Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) is an autosomal dominant disease with a reduced penetrance that is caused by a mutation in the transthyretin (TTR) gene [Citation1]. More than 100 mutations in the TTR gene have been found that causes ATTR and give rise to different phenotypes of the disease [Citation2,Citation3]. The most common neuropathic mutation is V30M, which is found in endemic areas in North Sweden, in France, in Portugal and in Japan; however, sporadic cases exist worldwide [Citation4]. Despite derived from the same V30M mutation, the phenotype of the disease differs both between and within populations. The Portuguese population has an early onset and high penetrance compared to the Swedish population that, in general, has a late onset and low penetrance [Citation5,Citation6]. The underlying causes for these differences have been broadly investigated, but so far no definite explanation has emerged.

TTR is mainly synthesized and excreted by the liver, but is also marginally produced and locally distributed by the choroid plexus and retina [Citation1]. Upon secretion from the liver, the tetrameric structure of the mutated protein is more disposed to dissociate into its monomeric counterparts. These monomers refold and aggregate into amyloid fibrils that are found in peripheral tissue, however, the exact process of fibrils formation is not fully understood [Citation7–9]. Amyloid fibrils can be found in most peripheral tissue, including nerve tissue, heart and abdominal fat. Interestingly, one place where only small amounts of amyloid fibrils have been found is in the liver, the source of the amyloidogenic protein.

One accepted treatment for variant ATTR amyloidosis is liver transplantation where the source organ of variant TTR production is exchanged by another producing wild type only. This often halts the disease progress. However, some patients continue to deteriorate probably due to deposition of amyloid fibrils derived from wild type TTR in target tissues [Citation10,Citation11]. To ameliorate organ shortage, domino liver transplantation is performed, where the variant TTR producing liver is used for transplantation of a patient with end-stage liver disease. It was originally assumed that it would take a similarly long time for the recipient to develop the disease, i.e. at least 20 years or longer. However, recent reports have revealed that the domino liver recipients may develop symptoms much earlier than this, i.e. 7–8 years, and amyloid deposits have been found in the tissue as early as 4 years after transplantation [Citation12–15].

Recently, TTR-stabilization by means of a small molecule (Tafamidis, Pfizer Inc., USA) was shown to decrease disease progression in ATTR V30M amyloid patients. However, even though disease progression diminishes, progression was observed even though a high level of stabilization of the TTR-tetramer was achieved [Citation16,Citation17]. Thus, stabilization of circulating TTR appears not to be sufficient to halt disease progression.

Micro array transcription analysis can be used to measure expression levels of all known genes in the genome. Our aim with the present study was to investigate how patients’ livers differ in gene expression profile compared to controls and how the differentially expressed genes could affect the disease progress. Further, we aimed at understanding the impact of fibril formation in target tissues, and if deposits change the expression of genes from these tissues. Gene expression in liver tissue, the source organ, and adipose tissue, the target organ, of histopathological and genetically proven ATTR V30M patients were compared to control material from non-ATTR amyloid individuals to identify processes that are specific for the disease. This could enable an identification of possible genetic factors facilitating amyloid fibril formation both in the source and targeting organs in ATTR amyloidosis patients.

Methods

Patients

Nine Swedish ATTR V30M patients with histopathological and DNA confirmation of the diagnosis that were undergoing liver transplantation were enrolled in the study between March 2009 and April 2010. Liver biopsies were collected during the transplantation, and immediately placed in RNAlater (Qiagen) and stored in −80 °C until use. The nine control liver biopsies were obtained from cancer patients that underwent curatively intended liver resection due to malignant disease. One of these patients suffered from liver metastasis originating from a gastro intestinal stromal tumor, one from a liver metastasis originating from an adenocarcinoma in the small intestine, one had a hepatocellular carcinoma and the remaining six patients had colorectal liver metastases. None of the patients had received cytostatic treatment within 3 months prior to surgery and none of the patients suffered from diabetes. Macroscopically healthy liver tissue was collected from the liver, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen in the operating theatre and stored in −80 °C. For clinical details of patients and controls ().

Table 1. Clinical data on patients and controls from which biopsies were collected. p Values are shown on the difference between groups.

In addition to the liver biopsies, abdominal fat biopsies from twelve Swedish ATTR V30M patients with amyloid deposits and seven healthy living controls without any clinical features were also collected. The material for the study was secured during the period October 2008 to November 2010 (). The fat biopsies were also immediately placed in RNAlater and stored in −80 °C until use. In all fat biopsies from ATTR V30M patients, amyloid deposits had been detected by Congo red staining and examination in polarized light. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Umeå University (Dnr: 06-084M).

Total RNA preparation

Total RNA was isolated from the biopsies using the miRNeasy Mini Kit or the Allprep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo scientific, Wilmington, DE) and the integrity of the RNA was analyzed with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA). All RNA samples with a RIN value >7 were accepted for further preparation.

Microarray gene expression

Using the Illumina Totalprep RNA Amplification Kit and protocol (Ambion, Austin, Texas), aliquots of total RNA were converted to biotinylated double-stranded cRNA. The biotin labeled cRNA samples from liver and fat biopsies were hybridized on a Sentrix HumanRef-12 Expression Beadchip (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and incubated with streptavidin-Cy3. The Beadchips were scanned on the Illumina Beadstation GX (Illumina).

Real time PCR

Eleven significantly differentially expressed genes with high expression levels from liver, and fat were selected for validation of Illumina results. Total-RNA samples were converted into cDNA using Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase kit (Qiagen), according to manufacturer’s protocol. All probes for analysis were ordered from Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA. Real time PCR was conducted using TaqMan gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s instructions. PPIA was used as endogenous control for all biopsies.

Bioinformatics and statistics

The non-parametric test Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess differences in age and sex between the patient and control groups. Data quality control was performed using the Genome Studio software (Illumina) according to instructions [Citation18], and Simca P+ software (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden). Samples that were obvious outliers according to Hotelling’s T2 values [Citation19] in the cluster analysis and PCA analysis were removed from further analysis. To determine differentially expressed genes data were analyzed using Genome Studio software. Data were normalized using cubic spline with background correction. As error model Illumina custom was used. Probes with average signal <50, detection p value > 0.05 or fold change < ±1.5 were filtered away. Benjamini Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing was used and only the tests of difference in expression with a q value < 0.05 were considered significant.

ErmineJ software (http://erminej.chibi.ubc.ca/) [Citation20] was used for the gene list analysis. The software uses Gene Ontology (GO) terms as gene lists and gene score resampling was used as a method for analyzing significant gene lists. To be classified as significant each gene list had to have a FDR under 0.05 and a multifunctionality score under 0.80.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is an unsupervised projection method that was applied to the data set to try to cluster samples with similar gene expression profiles. PCA models were created using the Simca P+ software (Umetrics). For the analysis, the entire data set was used but filtered to remove probes mostly displaying background noise. All probes with signal average <50, and detection p value > 0.05 were removed. Samples that were obvious outliers and did not cluster with others were removed from further analysis. Orthogonal projection to latent structures – discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and projection to latent structures – discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) are methods that use supervised multivariate regression to model and predict data. OPLS-DA was applied to the filtered data set for selection of transcripts with Variable importance in the projection (VIP) values over 2. VIP is a value determining how much the variable is contributing to the discrimination between classes. Classification analysis was performed on parts of the data set with VIP > 2 using PLS-DA. For classification a model with all except one sample were build and the last sample predicted into the model. The procedure was repeated until all samples had been predicted.

Results

Transcription analysis of liver biopsies

Liver biopsies from nine ATTR V30M amyloid patients and nine controls were used for gene expression analysis. The Mann–Whitney U test displayed no difference between the patient and control group neither with regard to age (p = 0.11) nor sex (p = 0.62). Without FDR correction 3060 transcripts were found significant differentially expressed between patients and controls. The FDR correction reduced the number of significant differentially expressed transcripts to 742, corresponding to 640 genes. Of these, 306 genes were found up-regulated and 334 genes were found down-regulated in patients compared to controls. Fifty of the most significant up- or down-regulated genes between patients and controls can be found in Figure S1. To validate the results from the Illumina micro array, real time PCR was performed on selected genes (Figure S2). The results were coherent with the micro array results.

Transcription analysis of fat biopsies

Gene expression analysis on abdominal fat biopsies from twelve ATTR V30M patients and seven controls were performed. Of these, two patient biopsies did not pass quality control and were excluded. The Mann–Whitney test showed no difference between the patient and control group neither with regard to age (p = 0.07) nor sex (p = 1). When comparing the seven control fat biopsies to the ten patient biopsies, 515 significant differentially expressed transcripts were found when not correcting with FDR. However, after correction with FDR, no significant differentially expressed transcripts remained (Table S1).

Real time PCR on heart and fat biopsies using selected genes was coherent with micro array results (Figure S2).

Sample classification by multivariate data analysis

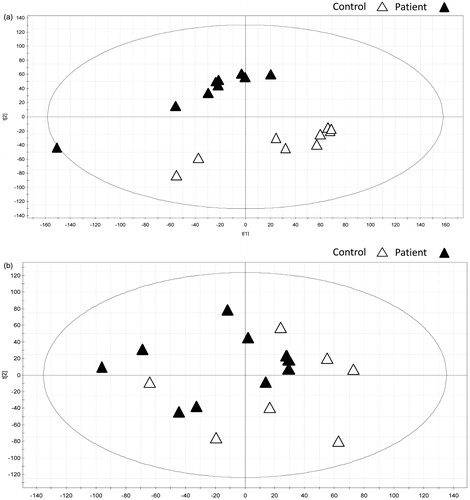

PCA analysis was performed and score plots on patient and control liver biopsies showed a distinct grouping into clusters separating the groups. This was true for all samples except one patient, which was a moderate outlier. The model was described by two components explaining 50% (R2X) of the variation in the data (). OPLS-DA analysis on the two classes was made to find genes contributing to the class separation. Two hundred and nine transcripts had a VIP value >2. Corresponding genes that also had a significant FDR value from the differential expression analysis resulted in 164 genes listed in Table S2. A PLS-DA model with all but one sample with the transcripts with VIP > 2 was created and the last sample was predicted into the model. This was repeated for all samples and the model always predicted the sample into the correct group (Table S3).

Figure 1. PCA analysis on (a) liver and (b) fat from patients (closed triangles) and controls (open triangles).

PCA analysis on fat biopsies revealed no clustering when comparing patients to controls (). A PLS-DA model of this tissue could not be used to predict the sample group (data not shown). The spreading of the patients’ samples in the PCA analysis indicates that the fat tissues have a gene expression profile comparable to that of the controls.

Functional pathways of significant genes

To determine which pathways are most affected in ATTR patients’ liver, gene lists analysis using GO terms was performed. When comparing patients to controls six ontologies were still significant after correction with FDR. The two ontologies with the most significant p values were Protein folding and Endoplasmic reticulum lumen (). Similar results were obtained when doing PCA analysis on the ontologies (data not shown). Gene list analysis on data from fat biopsies was not done since the number of differentially expressed genes was so low.

Table 2. Top differentiated GO terms when performing gene list analysis. Differences between patients and controls are displayed. FDR correction for multiple testing was used and q value <0.05 was considered significant.

Discussion

The tissues included in the present study were chosen because of their role in the disease, where liver represents the main source of the amyloidogenic protein (TTR), whereas fat represent target organs affected by amyloid fibril deposition. Our main objectives were to understand the different tissues’ gene expression profiles, and how they relate to their role in the disease, i.e. source or targeted organ.

The main findings were the pronounced different gene profile in ATTR amyloid patients’ livers (source organ) compared with that of the controls, and secondly, that targeted tissues’ gene profile (in fat) did not differ from that of the controls.

In trying to elucidate if these marked differences in the livers’ gene expression profile is enough to separate patients from controls, PCA analysis were performed on liver and fat biopsies. In the liver biopsies, there was a clear clustering between patients and controls. In addition, the genes derived from the OPLS-DA analysis for classification purposes enabled the creation of a model that could accurately predict the affection status of all the liver samples. This further strengthens the evidence that there are real differences in gene expression profiles between patients and controls. Furthermore, the top two pathways involved were protein folding and endoplasmic reticulum lumen, this is very interesting considering the folding of the mutated protein in the ER. Some interesting genes that can be found included in these terms are PFDN6, DNAJC7, FKBP2 and ERP29, all of which are chaperones associated with the ER and co-chaperones [Citation21–24]. Interestingly, the patients had a lower expression of these genes than the controls. One could speculate that a reason for this might be that an inefficient protein folding pathway in the diseased allows for mutated TTR to pass more easily through the ER. FK506-binding protein 2 (FKBP2) is a peptidyl-prolyl-cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) that accelerates the folding of proteins [Citation25]. Members of the FKBP family were previously shown to bind to BiP, and the binding regulated by Ca2+. Binding of FKBP to BiP suppresses its ATPase activity, thereby diminishing its activity [Citation26]. Our results show a decrease in FKBP2 expression in patients, which would, assuming all members of the FKBP family have a similar effect, suggest an increased BiP activity. This on the other hand is contradicted by the decreased DNAJC7 expression. DNAJC7 is a member of the DNAJ heat shock protein 40 family, and acts as a co-chaperone regulating the activity of chaperones HSP70 and HSP90, including BiP [Citation22]. Thus, the decreased expression of DNAJC7 should downregulate the activity of BiP. However, our knowledge on the specific bindings between DNAJC7 and BiP is too limited to draw any further conclusions. PFDN6 is a subunit of the prefolding complex that chaperones actin and alpha-tubulin to cytosolic chaperonins [Citation27,Citation28]. ERP29 is a reticuloplasmin which is found in the ER lumen. Its exact function is not known, but it is suggested to play a part in the processing of secretory proteins [Citation29]. It should be pointed out that the exact function of several of these chaperons and co-chaperons are poorly understood, but taken together our findings point in the direction of an impaired ER/protein folding pathway in ATTR amyloid patients. If the ER/protein folding pathway is already impaired in the patients, it could explain why recipients receiving domino livers develop symptoms much earlier than predicted [Citation12–15]. In addition, an impaired quality control of proteins in the hepatocyte in ATTR amyloid patients should lead to secretion of misfolded TTR that easily can assemble into amyloid fibrils, a process that is not altered by stabilization of circulating TTR. This presents an explanation for the disease progression observed in the Tafamidis trial [Citation16,Citation17]

In contrast, when looking at fat biopsies, no clustering of patients or controls was seen. The absence of clustering in fat tissue further indicates that the overall gene expression profiles of fat tissues appear unaltered.

Sousa et al. [Citation30] investigated the gene expression profile in the salivary glands of ATTR amyloid patients, also a target organ for amyloid deposits. They found two genes, biglycan and NGAL, up-regulated in ATTR, findings that neither we nor Buxbaum et al. [Citation31] could repeat in other target tissues such as fat and heart. In the paper by Buxbaum et al. [Citation31], they measured gene expression in liver and heart tissue from transgenic mice with a 90-fold overexpression of the human wild type TTR gene. They could detect differences between young transgenic and non-transgenic mice in the livers for channels pathways, and in heart tissue for several pathways that include inflammation, chaperones, proteasomes and mitochondrial function. Apart from differences in tissues, their analysis was carried out on two independent RNA pools from three to five animals for each experimental condition, thereby preventing statistical analysis of intra-group variation and they may have identified genes that in our analysis would be designated as false positives.

Gomes et al. [Citation32] created a model in yeast that expresses wild type human TTR protein or the highly amyloidogenic L55P TTR protein. When comparing differences in protein occurrence between the L55P mutation and a control carrying an empty plasmid they found pathways affecting carbohydrate metabolism, translation and protein folding and degradation. The protein folding findings might be in agreement with our results in the liver biopsies. In another study by Brambilla et al. [Citation33], protein expression was measured in human abdominal fat tissue in patients with different types of amyloidosis and compared to patients without systemic amyloidosis, including some patients with localized organ amyloidosis. The authors found 87 proteins differentially represented between patients and controls. Their findings were based on the assumption that if the protein was present in at least 30% of the patients and in none of the controls, it was differentially represented. This method works for proteins expression analysis but is not suited for gene expression analysis where it could result in false positive findings. This methodological difference makes a comparison between our findings and those of Brambilla et al. [Citation33] problematic. It is important to stress that there are large differences between genomic and proteomic studies. Changes in protein expression do not have to be mirrored by similar changes in gene expression, since numerous post-transcriptional modifications affect the expression of a protein. In addition, proteins found in the proteomics analysis can be transported into the tissue during the amyloid formation process, and are therefore not derived from locally up-regulated genes. This is demonstrated by the findings of up-representation of TTR and SAP in the study by Brambilla et al. [Citation33].

αβ-crystallin protein has been reported to be represented intra-cellularly in skin biopsies from ATTR patients [Citation34]. However, another investigation of αβ-crystallin protein representation in fat biopsies reported pronounced inter-individual variation with a low expression in some patients, and an increased expression in others [Citation35]. In our gene expression analysis, we could not detect any difference in gene expression of αβ-crystallin between patients and controls in fat biopsies. These contradictory results could indicate that there are tissue specific differences in the protein expression of αβ-crystallin in ATTR amyloid patients, and that tissue reaction to amyloid deposition may vary between different organs; thus, gene expression profile in amyloid targeted organs may vary between different organs and tissues.

Limitations

A total of 18 liver samples and 17 fat samples for gene expression could be considered a small material. It is, however, comparable in size with other materials used for similar analysis, and also the first ATTR material that compared liver gene expression in human ATTR amyloid patients. Fat biopsies in general are not rich in RNA content, considering that adipose cells are not involved in as many biological processes and pathways as are liver cells; this decreases the chance of finding differences in gene expression. However, we have rigorously controlled the quality of the RNA, so we are convinced that our findings are correct. In addition, fat tissue is probably not representative for all target organs; thus our finding of an unaltered gene expression profile in fat may not be true for other organs with an imparied function caused by amyloid deposition. Another aspect that has to be thoroughly considered is that the control liver biopsies originate from patients with primary or liver-metastatic cancer. Although not optimal, the acquisition of liver biopsies from healthy individuals is not possible, therefore, the chosen material was one of the better available, and the sample was taken well outside the metastasis, i.e. in macroscopically healthy tissue, to ensure that no cancer cells were present in the sample. Addressing the issue of the different treatments of the patient and control biopsies, studies have shown that there are no significant differences in gene expression between snap-frozen material and material placed in RNA later [Citation36].

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the source organ, the liver, is subjected to profound changes in gene expression. In contrast, fat tissues’ gene expression profile remains largely unaffected. An impaired ER/protein folding pathway with differences in gene expression of chaperones was observed in the Swedish ATTR V30M population. These findings offer an explanation for the rapid onset of amyloid formation in patients receiving ATTR livers.

Declaration of interest

O.B.S. has participated in clinical trials of Tafamidis, and silencing RNA’s sponsored by Fold Rx (later acquired by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals) and Alnylam, respectively. He has also served in advisory boards for Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and Alnylam. The study was supported by grants from the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation (OBS), Central and Clinical ALF grants, Spearhead grant from Västerbottens County (OBS), from the patients’ associations FAMY/AMYL, Norr- and Västerbotten, and from the Association Francaise contre l’Amylose (VPB).

| Abbreviations | ||

| ATTR | = | hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis |

| ER | = | endoplasmic reticulum |

| FDR | = | false discovery rate |

| GO | = | gene ontology |

| OPLS-DA | = | orthogonal partial least square – discriminant analysis |

| PCA | = | principal component analysis |

| TTR | = | transthyretin |

| V30M | = | valine 30 methionine |

| VIP | = | variable importance in the projection |

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (271 KB)References

- Plante-Bordeneuve V, Said G. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:1086–97

- Saraiva MJ. Transthyretin mutations in hyperthyroxinemia and amyloid diseases. Hum Mutat 2001;17:493–503

- Connors LH, Lim A, Prokaeva T, Roskens VA, Costello CE. Tabulation of human transthyretin (TTR) variants, 2003. Amyloid 2003;10:160–84

- Benson MD. Leptomeningeal amyloid and variant transthyretins. Am J Pathol 1996;148:351–4

- Plante-Bordeneuve V, Carayol J, Ferreira A, Adams D, Clerget-Darpoux F, Misrahi M, Said G, et al. Genetic study of transthyretin amyloid neuropathies: carrier risks among French and Portuguese families. J Med Genet 2003;40:e120

- Hellman U, Alarcon F, Lundgren HE, Suhr OB, Bonaiti-Pellie C, Plante-Bordeneuve V. Heterogeneity of penetrance in familial amyloid polyneuropathy, ATTR Val30Met, in the Swedish population. Amyloid 2008;15:181–6

- Kelly JW, Colon W, Lai Z, Lashuel HA, McCulloch J, McCutchen SL, Miroy GJ, et al. Transthyretin quaternary and tertiary structural changes facilitate misassembly into amyloid. Adv Protein Chem 1997;50:161–81

- Hou X, Aguilar MI, Small DH. Transthyretin and familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Recent progress in understanding the molecular mechanism of neurodegeneration. FEBS J 2007;274:1637–50

- Lai Z, Colon W, Kelly JW. The acid-mediated denaturation pathway of transthyretin yields a conformational intermediate that can self-assemble into amyloid. Biochemistry 1996;35:6470–82

- Suhr OB, Ericzon BG. Selection of hereditary transthyretin amyloid patients for liver transplantation: the Swedish experience. Amyloid 2012;19 Suppl 1:78–80

- Ando Y, Ueda M. Diagnosis and therapeutic approaches to transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr Med Chem 2012;19:2312–23

- Stangou AJ, Heaton ND, Hawkins PN. Transmission of systemic transthyretin amyloidosis by means of domino liver transplantation. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2356

- Takei Y, Gono T, Yazaki M, Ikeda S, Ikegami T, Hashikura Y, Miyagawa S, et al. Transthyretin-derived amyloid deposition on the gastric mucosa in domino recipients of familial amyloid polyneuropathy liver. Liver Transpl 2007;13:215–18

- Goto T, Yamashita T, Ueda M, Ohshima S, Yoneyama K, Nakamura M, Nanjo H, et al. Iatrogenic amyloid neuropathy in a Japanese patient after sequential liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2006;6:2512–15

- Llado L, Baliellas C, Casasnovas C, Ferrer I, Fabregat J, Ramos E, Castellote J, et al. Risk of transmission of systemic transthyretin amyloidosis after domino liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2010;16:1386–92

- Coelho T, Maia LF, Martins da Silva A, Waddington Cruz M, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Lozeron P, Suhr OB, et al. Tafamidis for transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology 2012;79:785–92

- Coelho T, Maia LF, da Silva AM, Cruz MW, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Suhr OB, Conceicao I, et al. Long-term effects of tafamidis for the treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol 2013; 260:2802–14

- Illumina I. Gene expression microarray data quality control. Available at: res.illumina.com/documents/products/technotes/technote_gene_expression_data_quality_control.pdf 2010

- Hotelling H. The generalization of Student’s ratio. Ann Math Stat 1992;2:360–78

- Lee HK, Braynen W, Keshav K, Pavlidis P. ErmineJ: tool for functional analysis of gene expression data sets. BMC Bioinformatics 2005;6:269

- Suaud L, Miller K, Alvey L, Yan W, Robay A, Kebler C, Kreindler JL, et al. ERp29 regulates DeltaF508 and wild-type cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) trafficking to the plasma membrane in cystic fibrosis (CF) and non-CF epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2011;286:21239–53

- Brychzy A, Rein T, Winklhofer KF, Hartl FU, Young JC, Obermann WM. Cofactor Tpr2 combines two TPR domains and a J domain to regulate the Hsp70/Hsp90 chaperone system. EMBO J 2003;22:3613–23

- Vainberg IE, Lewis SA, Rommelaere H, Ampe C, Vandekerckhove J, Klein HL, Cowan NJ. Prefoldin, a chaperone that delivers unfolded proteins to cytosolic chaperonin. Cell 1998;93:863–73

- Bush KT, Hendrickson BA, Nigam SK. Induction of the FK506-binding protein, FKBP13, under conditions which misfold proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J 1994;303:705–8

- Gothel SF, Marahiel MA. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases, a superfamily of ubiquitous folding catalysts. Cell Mol Life Sci 1999;55:423–36

- Zhang X, Wang Y, Li H, Zhang W, Wu D, Mi H. The mouse FKBP23 binds to BiP in ER and the binding of C-terminal domain is interrelated with Ca2+ concentration. FEBS Lett 2004;559:57–60

- Gao Y, Thomas JO, Chow RL, Lee GH, Cowan NJ. A cytoplasmic chaperonin that catalyzes beta-actin folding. Cell 1992;69:1043–50

- Sternlicht H, Farr GW, Sternlicht ML, Driscoll JK, Willison K, Yaffe MB. The t-complex polypeptide 1 complex is a chaperonin for tubulin and actin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993;90:9422–6

- Mkrtchian S, Sandalova T. ERp29, an unusual redox-inactive member of the thioredoxin family. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006;8:325–37

- Sousa MM, do Amaral JB, Guimaraes A, Saraiva MJ. Up-regulation of the extracellular matrix remodeling genes, biglycan, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. FASEB J 2005;19:124–6

- Buxbaum JN, Tagoe C, Gallo G, Walker JR, Kurian S, Salomon DR. Why are some amyloidoses systemic? Does hepatic “chaperoning at a distance” prevent cardiac deposition in a transgenic model of human senile systemic (transthyretin) amyloidosis? FASEB J 2012;26:2283–93

- Gomes RA, Franco C, Da Costa G, Planchon S, Renaut J, Ribeiro RM, Pinto F, et al. The proteome response to amyloid protein expression in vivo. PLoS One 2012;7:e50123

- Brambilla F, Lavatelli F, Di Silvestre D, Valentini V, Palladini G, Merlini G, Mauri P. Shotgun protein profile of human adipose tissue and its changes in relation to systemic amyloidoses. J Proteome Res 2013;12:5642–55

- Magalhaes J, Santos SD, Saraiva MJ. alphaB-crystallin (HspB5) in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Int J Exp Pathol 2010;91:515–21

- Lavatelli F, Perlman DH, Spencer B, Prokaeva T, McComb ME, Theberge R, Connors LH, et al. Amyloidogenic and associated proteins in systemic amyloidosis proteome of adipose tissue. Mol Cell Proteomics 2008;7:1570–83

- Mutter GL, Zahrieh D, Liu C, Neuberg D, Finkelstein D, Baker HE, Warrington JA. Comparison of frozen and RNALater solid tissue storage methods for use in RNA expression microarrays. BMC Genomics 2004;5:88