Abstract

Context: Specific soluble biomarkers could be a precious tool for diagnosis, prognosis and personalized management of osteoarthritic (OA) patients.

Objective: To describe the path of soluble biomarker development from discovery to clinical qualification and regulatory adoption toward OA-related biomarker qualification.

Methods and results: This review summarizes current guidance on the use of biomarkers in OA in clinical trials and their utility at five stages, including preclinical development and phase 1 to phase 4 trials. It also presents all the available regulatory requirements.

Conclusions: The path through the adoption of a specific soluble biomarker for OA is steep but is worth the challenge due to the benefit that it can provide.

Introduction

As given by its definition, a biomarker is a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention (Biomarkers Definitions Working Group, Citation2001). Biomarkers are not only essential for the understanding of pathological pathways but also for diagnosis, prognosis and follow up as previously described by Kraus et al. (Citation2011). In addition, they could be a valuable tool in the new era of personalized medicine. They include soluble analytes measured in biospecimens, such as blood and urine, anatomic features detected by radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or even functional measurements, such as gait analyses and histological measurements produced as a result of a joint tissue biopsy, such as a synovial biopsy. This paper is focused on soluble biomarkers, specifically to protein biomarkers, and discusses the milestones between biomarker discovery and clinical application.

Biomarkers can provide value at all stages of drug development. Biomarkers may be companion tools for drug development from in vitro screening to phase III clinical trials and also, at the post-marketing stage, for the individual follow-up of response to treatment (Kraus et al., Citation2015). Therefore, the collection of biospecimens is strongly recommended in all osteoarthritis (OA) clinical trials to determine whether biomarkers are useful in identifying patients most likely to receive clinically important benefits from an intervention; and to determine whether biomarkers are useful for identifying patients at earlier stages of OA in order to institute treatment at a time more amenable to disease modification. In addition, biomarkers might help to select progressors and by this allow reduction of both sample size and duration of clinical trials investigating structural effects.

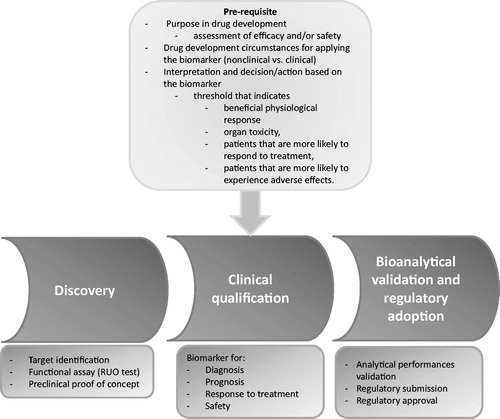

With respect to the complex nature of the disease, developing new biomarkers in OA represents a major challenge, which requires strong basic research and complementary clinical and regulatory expertise. In such context, it is best relying on a good definition of the intended purpose of the biomarker in qualification and a scientifically sound strategy in order to achieve regulatory/market adoption. For the identification of potentially interesting biomarkers, the discovery process can rely on in-depth understanding of cell biology combined to breakthrough “OMICs” technologies, such as mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Following discovery, efforts have to be made for developing and validating robust assays used to reliably quantify these new biomarkers in complex body fluids. This process is called “validation” and corresponds to verification of analytical performance characteristics (such as precision, accuracy, stability, etc.) as well as clinical correlation of a biomarker with a biological process or clinical outcome. Finally, clinical qualification activities have to be performed in order to confirm the clinical relevance of the biomarker in a particular context (i.e. drug discovery). Qualification is a process applied to a particular biomarker to support its use as a surrogate end-point in drug discovery, development or post-approval and, where appropriate, in regulatory decision-making (Biomarkers Definitions Working Group, Citation2001). There are many possible qualifying endpoints for an OA-related biomarker including signs (inflammation) and symptoms (pain), structure or functional outcomes in OA. In practice, the qualification process is gradual one correlating changes in a biomarker with change in state of joint. Biomarkers for drug development use can be divided into four categories according to the degree or level that the biomarker can be shown to be associated with the pathophysiological state or the clinical outcome. The four levels are exploratory, demonstration, characterization and finally surrogate level. The use of a surrogate endpoint as the basis for approval of a new drug requires prior agreement with the regulatory agency. Until now, none of the existing biomarker has been considered as a surrogate biomarker. The clinical qualification of biomarkers is a prerequisite in order to better designed clinical trial and to develop efficient therapies (Karsdal et al., Citation2014; Kraus, Citation2012).

Existing biomarkers can be categorized according to the OA process targeted as markers of cartilage degradation/synthesis, bone remodeling or synovial tissue degradation/activity. A system first introduced as BIPED by Bauer et al. (Citation2006) and van Spil et al. (Citation2010), and extended to BIPEDS by Kraus et al. (Citation2011) that classify the major types of biomarkers according their clinical background into six categories corresponding to burden of disease, investigational, prognostic, efficacy of intervention, diagnostic biomarkers and safety biomarkers. In 2011, OARSI/FDA osteoarthritis Biomarkers Working Group has classified biomarkers into four categories (exploration, demonstration, characterization and surrogacy levels) according to their current level of qualification for drug development (Kraus et al., Citation2011; Wagner et al., Citation2007). More recently, OARSI RCT Working Group published guidelines for soluble biomarkers assessment in clinical trials (Kraus et al., Citation2015). This document summarizes current guidance on the use of biomarkers in OA clinical trials and their utility at five stages, including preclinical development and phase I to phase IV trials.

The present review gives an industry perspective of the complex development lifecycle required for regulatory adoption of new biomarkers in the field of OA. It presents the extent of activities and issues associated with OMICS-based biomarker discovery, assay development and validation, and preclinical and clinical qualification ().

Biomarker discovery

The discovery of peptide-based biomarker could follow top–down or bottom–up processes. In the top–down approach, the sequences of interest for potential biomarkers are conceptualized using knowledge, computerized methods and/or bioinformatics that allows the prediction at a molecular level of the biological effects occurring during the pathology progression [e.g. in the cancer field (Baumgartner et al., Citation2011)]. This approach requires a deep understanding of joint biochemistry as well as of the surrounding tissues (musculoskeletal environment), which contribute to disease initiation and progression (Lotz et al., Citation2013; Mahjoub et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, a good knowledge of the pathophysiology of the disease at the molecular level is also required to know which targets are involved and when they act on the joint, leading to a fine cartography of the potential fragments/molecule, which could be used as biomarker (Man & Mologhianu, Citation2014).

This can be done by epitope mapping of proteins, which is known to be involved in the pathophysiological state being studied. The most popular OA biomarkers (i.e. Coll2-1, C2C, CTX-II) have been conceptualized using this top–down approach. Most of them are epitopes located in type II collagen, one of the most specific molecules of the articular cartilage matrix (Birmingham et al., Citation2007; Henrotin et al., Citation2007). Collagen is degraded by enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms in OA. Included in the native form of the parental proteins, biomarkers are very often undetectable but when degradation processes occur, new epitopes become detectable and then can reflect the catabolic level present in the affected joint. Other matrix proteins, such as aggrecan and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) have also contributed to get a better integrative view and understanding of the disease (Lohmander et al., Citation1989,Citation1994).

For example, C2C corresponds to the c-terminal neo-epitope generated by the collagenase-mediated cleavage of collagen type II triple helix (Poole et al., Citation2004). Coll2-1 is an amino acid sequence located in the triple helical part of type II collagen that is revealed after triple helix unwinding and cleavage by gelatinases. This sequence shows the particularity to contain one tyrosine, an aromatic amino acid sensitive to nitration, by among others, peroxynitrite (–ONOO). This chemical distinction was used to develop Coll2-1NO2, a biomarker of the oxidative-stress related cartilage degradation (Deberg et al., Citation2005). Coll2-1NO2 is well correlated with the c-reactive protein (CRP) indicating that this biomarker could be a marker of joint inflammation (Deberg et al., Citation2005,Citation2008).

In this case, the knowledge of the post-transcriptional and/or post-maturation of the proteins has been essential for the identification of such kind of biomarkers. Noteworthy, another limiting aspect of this top–down approach is the field of knowledge in a particular domain at a precise moment.

The second step and probably the most challenging one is the achievement of the concept by developing a functional bioassay from the theoretical sequence, and especially by using as reference in the immunoassay the peptide or protein fragments as close as possible than the actual form present in the biological fluids.

The proof-of-concept of these top–down biomarkers is achieved by identification and quantification of the biomarkers in biological fluids of representative patient population once the appropriate bioassay has been developed.

In the bottom–up approach (i.e. fibulin-3 fragments), biological fluids of representative patient population (i.e. OA patients) are compared to those of healthy population or of patients suffering of another disease (i.e. rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients or osteoporosis) using “OMICs” (i.e. proteomic, lipodomic, metabolomic) approaches (Henrotin et al., Citation2012). For example, comparative proteomic tools, such as two-dimensional differential gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) allow the identification of proteins and related degradation products that are significantly modified between groups (Gharbi et al., Citation2011). Other techniques, such as immunoaffinity enrichment, depletion, protein chip array methods have also allowed the identification and/or the verification of many proteins that are directly or indirectly involved in the pathological processes of OA (Hsueh et al., Citation2014). The main limitation of this bottom–up approach comes from the limitation of the OMIC techniques, more particularly, the sample processing involving enzymatic digestion and the range of molecular weight or predefined proteins investigated by these methods. A prototype assay is then developed from a small number of samples leading to the proof of concept.

From preclinical proof of concept to clinical qualification

Qualification of the biomarker is related to its meaning – the evidentiary process of linking a biomarker with biological processes and clinical endpoints – while the validation is related to analytical performances of the assay, regardless of particular clinical context.

Four levels of qualification were defined (Wagner et al., Citation2007). Biomarkers are qualified through their use from in vitro/preclinical studies to clinical trials. Preclinical evidence or proof-of-concept qualifies the biomarker at the exploratory level for its use in R&D as development tool. When associated with clinical outcome, biomarker is at the demonstration level. If the demonstration is performed reproducibly in several prospective clinical studies, the biomarker is at the characterization level. Highest level of qualification is surrogacy wherein the biomarker is able to substitute a clinical endpoint. At this time, there are no surrogate biomarkers.

Patient phenotyping is critical to the success of biomarker qualification. OA is a tremendously heterogeneous group of different phenotypes of disease at different joint locations and different combinations thereof. It is possible that biomarkers will perform very differently in these different phenotypes, e.g. markers for early onset post-traumatic knee OA might be very different from valid biomarkers for erosive hand OA.

The subject sample needs not only to be carefully detailed with respect to conventional demographic characteristics, i.e. age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities, etc., but also the targeted OA phenotype, joint location(s) and disease stage depending on study purpose, such as diagnostic/burden of disease, prognosis, monitoring efficacy or safety. As demonstrated by the experience with prostate cancer biomarkers, there is a need for a standardized procedure to qualify new biomarkers to achieve comparability (Schalken, Citation2010). In addition to comprehensive phenotyping, very precise conditions are also required for sample collection, handling and storage.

Thus, when using a biomarker as a substitute for a clinically meaningful endpoint, one must first be clear about the clinically meaningful endpoint for which the biomarker is a proposed surrogate (Fleming & Powers, Citation2012). The objectives pursued in such trials should be clearly defined as to demonstrate the clinical benefits in relation to the intended use of the biomarker ().

Table 1. Intended use of biomarkers in clinical trial.

For instance, a biomarker qualified for OA progression, and modified by interventions that block progression, might be used as drug development and perhaps someday, drug approval as a chondroprotective agent.

In 2013, the Qualification Process Working Group (FDA) (FDA et al., Citation2013) has published guidance for the qualification process for drug development tools (DDT). DDTs are methods, materials, or measures that aid drug development including biomarkers, clinical outcome and animal models. Biomarker qualification has been recognized by the FDA as a significant area of interest, either as a single biomarker or as composite biomarker, the latter consisting of several individual biomarkers combined in a stated algorithm to obtain an easily interpretable readout. The guidance also contains an indication on how sponsor should formulate the so-called “context of use” (COU). These include a “use statement” (the name of the biomarker and the specific purpose for use in drug development) and a description of conditions for the biomarker to be used in the qualified setting that are termed “condition for qualified use” (the conditions for the use of the biomarker in the qualified setting).

Biomarkers could be involved and provide value in OA-related drug development at five levels, from preclinical development to phase 1–4 clinical trials. summarizes considerations for each of these phases of drug development and trial work.

Table 2. Five phases of drug development.

In addition to clinical trials intended to show clinical benefits of the biomarker in development, some studies must be set up to evaluate the influence of environmental factors on the reliability of the kit, such as circadian rhythm and seasonality of biomarkers in individuals, the impact of the sampling and sample preparation procedures on biomarker levels in biological fluids.

Consequently the clinical methodology described in the study protocol should address the following elements:

Sound trial/statistical design and clear objectives.

Primary and secondary outcomes, including, if soluble biomarkers, the analytical performance of the measurement method and the context of use of the biomarker.

Representative population (inclusion/exclusion = bias).

Solid procedures for data collection and biological sample collection and analysis.

Fully-characterized cohorts and samples.

Robust statistics and modeling.

In conclusion, from design to acceptation as clinical endpoint, a large number of (pre)clinical trials are needed to support the clinical qualification of innovative biomarkers.

Regulatory affairs and quality concerns around biomarkers including bioanalytical validation

This section presents key regulatory considerations and quality certifications/guidance for use of OA biomarkers in humans in the scope of product commercialization with a focus on in vitro diagnostic (IVD) kits.

In fact regulation requirements for IVD kits are much more stringent than those for Research Use Only (RUO) kits due to their intended uses. Following the FDA definition, IVD Products are reagents, instruments and systems intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, including a determination of the state of health, in order to cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent disease or its sequelae. RUO kits are devices not intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions. They are intended for use in research or investigations on human samples and they also may be marketed for and used in the research and investigation of other regulated products. They do not need to comply with safety and efficiency regulatory requirements but they all need to be labeled with the mention telling that the intended use is for research only.

International regulatory framework is complex. Classification and regulation still need to be harmonized. Currently, three regions lead the debate and their own regulations are internationally recognized: the USA (with Food and Drug Administration, FDA), Europe (with European Commission, EC) and Japan (with Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, PMDA). IVD products are part of medical devices (MD). Nevertheless IVDs are submitted to a specific regulatory system.

Official attempt for harmonization is led by International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF), which is formerly called as Global Harmonization Task Force; http://www.imdrf.org/ (GHTF) and created by representatives from the MD regulatory authorities of Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, the European Union, Japan and the United States, as well as the World Health Organization (WHO). This forum provides guidance for international harmonized good practices in the MD sector.

US regulations

Marketing IVD products in USA requires FDA approval. FDA classifies MD into three categories depending on patient and public health risks. As device class increases from Class I, to Class II to Class III, the regulatory controls also increase (). Classification procedure of Medical Devices is described in Code of Federal Regulation 21 part 860 (21 CFR 860).

Table 3. FDA classification for medical device.

Other codes of federal regulation related to MD have to be taken into account:

21 CFR 820 for quality system regulation of MD: Requirements for Good Manufacturing Practices are described in this part. These requirements govern the methods used in, and the facilities and controls used for, the design, manufacture, packaging, labeling, storage, installation and servicing of all finished devices intended for human use.

21 CFR 807 Establishment registration and device listing for manufacturers and initial importers of devices: This part provides Medical Device registration procedures (dossier “510k”).

And many other FDA guidelines on companion IVD, IVD per therapeutic indication.

European regulations.

Currently in Europe, for biomarkers used as IVD MD in routine, regulation is described by EC Directive 98/79/EC on CE-marking. IVDs are classified into two groups: list A (high risk and including HIV, HTLV I and II, Hepatitis B, C and D) and list B (moderate risk). List B IVDs are marketed following self-conformity assessment while list A IVDs are overseen by notified bodies. The European Commission is about to release new directives, which will make a better matching between IVD and Medical Device regulations while maintaining their own specificities. A list of changes is presented in . This new directive is submitted to amendments. Then this list represents the current status and is non-exhaustive.

Table 4. List (non-exhaustive) of changes in the EC guidance.

A common part in the US and CE regulation is the establishment of analytical performances of the IVD in order to achieve the device suitability for the purposes specified by the manufacturer. Validation refers to the measurement performance characteristics of a biomarker. Validation of a bioanalytical method is needed to demonstrate that it is reliable and reproducible for the intended quantitative measurement of the biomarker(s) in a given biological matrix (e.g. blood, plasma, serum or urine). During the development and validation phases, many factors must be investigated to achieve appropriate assay robustness and to guarantee continuous performance. Depending on the technique developed to reliably measure the biomarker, the method used to assess these performances can vary. is an attempt to define bioanalytical method performances and is adapted from FDA guidance for industry (FDA et al., Citation2013), European Directive 98/79/EC on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and published articles (Armbruster & Pry, Citation2008; Kraus et al., Citation2011), which refer to commonly used definitions in the market.

Table 5. Summary of the current guidance on analytical validation processes specific to biomarkers.

In addition to regulatory guidelines, manufacturers shall comply with quality standards which are provided by International Standardization Organization (ISO) and well represented by ISO9001:2008 Quality Management System, ISO13485 Design & Development and manufacturing of medical devices, ISO17025/GLP for clinical labs, ISO15189/CLIA for medical labs, ISO 15198 Validation of user quality control procedures by the manufacturer.

Each manufacturer must pay attention to change in regulations. Regulatory intelligence is the process of monitoring the current regulatory environment and anticipating the shape of future regulations, guidelines, policies and legislations. It requires expertise and quality/regulatory oversight.

Conclusion

The path through the clinical qualification, acceptance by regulatory authorities and market of a biomarker is steep. However, the benefit that biomarker can provide in the understanding of the pathogenesis process and in treatment development is worth the challenge. The extensive use of biomarkers in clinical trials could lead to a faster biomarker qualification step. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to collect biological fluid in clinical trials. There is now a panel of biomarkers that can be measured in urine or serum with well validated techniques and demonstrated to be associated with imaging OA features. These biomarkers, even if they cannot be considered as surrogate biomarkers, can be used as drug development tools at all stages. They investigate the effects of a drug on joint tissues metabolism and then are indicative of its biological activity on joint tissue. Besides the symptomatic and structural effects, the metabolic effect of an intervention should be considered, mainly in subject with high risk of OA. Of course, this requires the demonstration that a metabolic response prevents the onset or progression of the disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Christelle Boileau for her assistance in manuscript preparation.

Declaration of interest

YH is the founder and the President of Artialis SA and Synolyne Pharma, two spin-off companies of the University of Liège. He has also received consulting fees from Nestle and Tilman SA, LABHRA and speaking fees from BioIberica, Royal Canin, Expanscience, AC, JVDP and MG are employes of Artialis S.A.

References

- Armbruster DA, Pry T. (2008). Limit of blank, limit of detection and limit of quantitation. Clin Biochem Rev 29:S49–52

- Bauer DC, Hunter DJ, Abramson SB, et al. (2006). Classification of osteoarthritis biomarkers: a proposed approach. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 14:723–7

- Baumgartner C, Osl M, Netzer M, Baumgartner D. (2011). Bioinformatic-driven search for metabolic biomarkers in disease. J Clin Bioinform 1:2. doi: 10.1186/2043-9113-1-2

- Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. (2001). Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther 69:89–95

- Birmingham JD, Vilim V, Kraus VB. (2007). Collagen biomarkers for arthritis applications. Biomark Insights 1:61–76

- Deberg M, Dubuc JE, Labasse A, et al. (2008). One-year follow-up of Coll2-1, Coll2-1NO2 and myeloperoxydase serum levels in osteoarthritis patients after hip or knee replacement. Ann Rheum Dis 67:168–74

- Deberg M, Labasse A, Christgau S, et al. (2005). New serum biochemical markers (Coll 2-1 and Coll 2-1 NO2) for studying oxidative-related type II collagen network degradation in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13:258–65

- FDA, USDOHAHS, CDER, CVM. (2013). Guidance for industry: bioanalytical method validation. Revision 1 ed. Silver Spring (MD): Food and Drug Administration

- Fleming TR, Powers JH. (2012). Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in clinical trials. Stat Med 31:2973–84

- Gharbi M, Deberg M, Henrotin Y. (2011). Application for proteomic techniques in studying osteoarthritis: a review. Front Physiol 2:90. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00090

- Henrotin Y, Addison S, Kraus V, Deberg M. (2007). Type II collagen markers in osteoarthritis: what do they indicate? Curr Opin Rheumatol 19:444–50

- Henrotin Y, Gharbi M, Mazzucchelli G, et al. (2012). Fibulin 3 peptides Fib3-1 and Fib3-2 are potential biomarkers of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 64:2260–7

- Hsueh MF, Onnerfjord P, Kraus VB. (2014). Biomarkers and proteomic analysis of osteoarthritis. Matrix Biol 39:56–66

- Karsdal MA, Christiansen C, Ladel C, et al. (2014). Osteoarthritis – a case for personalized health care? Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22:7–16

- Kraus VB. (2012). Patient evaluation and OA study design: OARSI/biomarker qualification. HSS J 8:64–5

- Kraus VB, Blanco FJ, Englund M, et al. (2015). OARSI Clinical Trials Recommendations: soluble biomarker assessments in clinical trials in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23:686–97

- Kraus VB, Burnett B, Coindreau J, et al. (2011). Application of biomarkers in the development of drugs intended for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 19:515–42

- Lohmander LS, Dahlberg L, Ryd L, Heinegard D. (1989). Increased levels of proteoglycan fragments in knee joint fluid after injury. Arthritis Rheum 32:1434–42

- Lohmander LS, Saxne T, Heinegard DK. (1994). Release of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) into joint fluid after knee injury and in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 53:8–13

- Lotz M, Martel-Pelletier J, Christiansen C, et al. (2013). Value of biomarkers in osteoarthritis: current status and perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis 72:1756–63

- Mahjoub M, Berenbaum F, Houard X. (2012). Why subchondral bone in osteoarthritis? The importance of the cartilage bone interface in osteoarthritis. Osteoporos Int 23:S841–6

- Man GS, Mologhianu G. (2014). Osteoarthritis pathogenesis – a complex process that involves the entire joint. J Med Life 7:37–41

- Poole AR, Ionescu M, Fitzcharles MA, Billinghurst RC. (2004). The assessment of cartilage degradation in vivo: development of an immunoassay for the measurement in body fluids of type II collagen cleaved by collagenases. J Immunol Methods 294:145–53

- Schalken JA. (2010). Is urinary sarcosine useful to identify patients with significant prostate cancer? The trials and tribulations of biomarker development. Eur Urol 58:19–20

- van Spil WE, Degroot J, Lems WF, et al. (2010). Serum and urinary biochemical markers for knee and hip-osteoarthritis: a systematic review applying the consensus BIPED criteria. Osteoarthr Cartil 18:605–12

- Wagner JA, Williams SA, Webster CJ. (2007). Biomarkers and surrogate end points for fit-for-purpose development and regulatory evaluation of new drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther 81:104–7