ABSTRACT

Background: This study analysed parents’ positive and negative appraisals of the impact of raising children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD) on family life.

Method: Mothers (n = 52) and fathers (n = 27) of 56 children with PIMD completed a questionnaire focused on their positive and negative appraisals of the impact of childhood disability on family life. Scale means (ranging from 10 to 40) were calculated, as was the relationship between the two subscales.

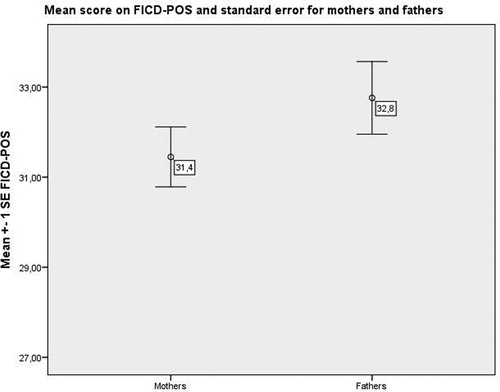

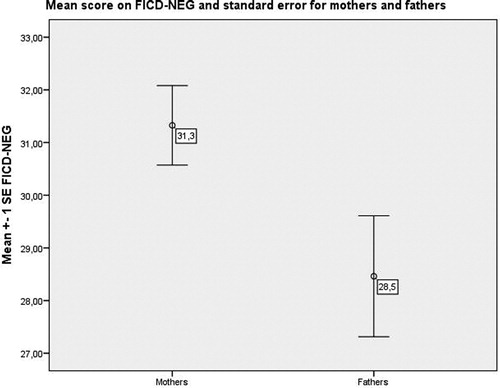

Results: Mothers and fathers indicated that their children affect family life both positively (M = 31.4 and 32.8, respectively) and negatively (M = 31.3 and 28.5, respectively). Only fathers showed a positive significant relationship between the positive and negative subscales.

Conclusions: Parents’ positive and negative appraisals co-occur. Although parents positively appraise the impact on family life, their substantial negative appraisals demand tailored support for families raising children with PIMD with a strong focus on practical support.

Children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD) are characterised by their profound intellectual and severe physical disabilities, resulting in little or no apparent understanding of spoken language (Nakken & Vlaskamp, Citation2007). Sensory impairments often co-occur as well as health problems (Nakken & Vlaskamp, Citation2007; Van Timmeren, Van der Putten, Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, Schans, & Waninge, Citation2016). A consequence of this combination of disabilities is the need for pervasive support, which makes raising a child with PIMD a highly demanding task for parents. Family systems theory views families as complex and interactive systems and acknowledges the needs of all family members, not just those of the family member with a disability (Seligman & Darling, Citation2009).

A recent study into families with a child with PIMD showed that mothers and fathers both spend an amount of time on caretaking tasks which far exceeds the usual time parents spend on typically developing children (Luijkx, Van der Putten, & Vlaskamp, Citation2017), which corresponds with previous research (Mencap, Citation2001; Tadema & Vlaskamp, Citation2010). Although the more objective consequences of raising children with PIMD (in terms of time and care tasks) have been studied, Tadema and Vlaskamp (Citation2010) also show that this does not necessarily reflect the subjective impact on the family life of parents. In fact, some studies report positive experiences in parents raising children with intellectual disability in addition to negative experiences and parental stress (Hastings & Taunt, Citation2002). Positive and negative emotions can coexist independently during times of distress and perform protective functions (Blacher, Baker, & Berkovits, Citation2013; Trute, Hiebert-Murphy, & Levine, Citation2007). It is important to understand not only the negative experiences but also the positive ones, because these can be viewed as a form or outcome of coping for parents. Several studies describe that positive experiences can be regarded as a buffer for stressful experiences (Folkman, Citation2008; Folkman & Moskowitz, Citation2000).

Although insight into the subjective impact of raising a child with PIMD on family life is important, there have been no studies so far exploring parents’ subjective appraisal of the impact of raising a child with PIMD. Studies into the parental appraisal of childhood disability on family life were predominantly conducted in families with children with less pervasive disabilities, or families with children with a broader range of disabilities. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to explore parents’ positive and negative appraisals of the impact of raising a child with PIMD on family life for mothers and fathers, and more specifically describe what aspects parents appraise as positive or negative. Research shows that parental perceptions and experiences of family-centred support are strong predictors of family quality of life (Davis & Gavidia-Payne, Citation2009). Knowing more about parental appraisals of the impact of raising a child with PIMD on family life helps us to understand which specific aspects influence family quality of life both positively and negatively. This enables us to consider how support should be tailored better to fulfil families’ wishes and needs and help them sustain their care tasks over an extensive period.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 52 mothers and 27 fathers living in the Netherlands volunteered to participate in this study (). Participants were included if their child had a severe or profound intellectual disability (IQ score < 35 points or a developmental age < 48 months) and a motor disability, and was still living at home. In 23 families both parents participated, while in 33 families one of the parents participated. The mean age of the parents was 41.7 years old (range: 25.7–60.5; SD 6.9). The mean age of the children with PIMD was 9.8 years (range: 1.8–34.3; SD 6.5). All children had additional impairments (see ). The formal support families received ranged from 18 to 60 hours per week, with an average of 40 hours per week (SD 9.9). Half the children visited a facility for respite care for at least one night per month.

Table 1. Participant and family characteristics.

Table 2. Characteristics of the children with PIMD (n = 56).

Questionnaire

The family impact of childhood disability instrument (FICD) (Trute & Hiebert-Murphy, Citation2005) was translated from English into Dutch. This questionnaire assesses the parents’ positive and negative appraisals of the impact of their child’s disability on family life. The FICD consists of an overall question: “In your view, what consequences have resulted from having a child with PIMD in your family.” This question is followed by a list of 10 positive and 10 negative types of impact which can be scored on a 4-point Likert scale of 1 (not at all) to 4 (substantial degree). A positive (FICD-POS) and negative (FICD-NEG) subscale can be calculated by summing the items from each subscale. The sum score of both scales varies theoretically from 10 to 40. Internal consistency for the Dutch version of the FICD and the current sample varied from acceptable to high for mothers and fathers on the positive and negative subscales (ranging from 0.67 to 0.81). A principal component analysis with varimax rotation based on the data from the present study confirmed the two subscales in the current study, with FICD-POS explaining 15.2% and FICD-NEG explaining 23.6% of total scale variance.

Design and procedure

In this cross-sectional study, participants were recruited in several ways. First, the parents who had participated in a previous study were asked to participate in this study as well: 54 parents (97.4%) agreed to participate. Second, a call was posted on several websites for parents of “children with complex needs”, on social media and circulated by the families themselves, resulting in 25 participants. These participants completed the questionnaire online. Participants were informed that confidentiality and privacy was guaranteed, in accordance with the Ethics Committee Pedagogical and Educational Sciences (Citation2012).

Analysis

Scale means were calculated for the FICD-POS and the FICD-NEG by adding up the scores of the items belonging to each subscale. The relationship between the two subscales was calculated for mothers and fathers using two Pearson’s correlation coefficients. An error bar was created for mothers and fathers in both subscales. A detailed overview of the scores (in %) of mothers and fathers on the individual items from both FICD subscales is presented. Items which were substantially positively or negatively appraised by the majority of parents (>50%) are described.

Results

Positive and negative appraisal of the impact on family life

Mothers rate the positive appraisal of the impact of raising a child with PIMD on family life with a mean score of 31.4 (range: 17–39, SD 4.7) and the negative appraisal with a mean score of 31.3 (range: 16–40, SD 5.3). Fathers rate the positive appraisal of the impact of raising a child with PIMD on family life with a mean score of 32.8 (range: 24–40, SD 4.0), and the negative appraisal with a mean score of 28.5 (range: 14–37, SD 5.9). For fathers, there was a positive relationship between the positive and negative subscale, r = .44, p < .05. For mothers, the two subscales are not significantly related (r = .24, p = .2). Based on and , fathers’ scores seem to be less negative than mothers’ scores, positive scores are more similar among mothers and fathers.

Overview of negative and positive impacts on mothers and fathers

gives a more detailed overview of the scores (in %) of mothers and fathers on the individual items of both FICD subscales. Concerning the negative subscale, more than half the parents indicated negative consequences to a substantial degree in their lives for 4 out of 10 items (40%). These items concern the topics “looking after a child with disability created extraordinary time demands”, “it has led to additional financial costs”, “it has led to unwelcome disruption of normal family routines”, and “a reduction in time parents could spend with friends”.

Table 3. Scores of mothers and fathers on the negative and positive subscales.

The scores on the positive subscale show that more than half of the parents appraised the following items as positive in their lives: “awareness of family members of other people’s disability-related needs and struggles” and “coming to terms with what should be valued in life”. More than half of mothers rated the item “the experience has helped me appreciate how every child has a unique personality and special talents” as positive. The majority of fathers indicated that raising a child with PIMD led to the following three positive consequences on their family lives to a substantial degree: “the experience made us more spiritual”, “family members have become more tolerant of differences in other people and more accepting of physical or mental differences between people”, and “it has led to an improved relationship with spouse”.

Discussion

This study explored the parents’ positive and negative appraisals of the impact of children with PIMD on family life. Based on the results, it can be concluded that positive and negative appraisals co-exist, which corresponds with several studies in families with children with disabilities (Hastings & Taunt, Citation2002; Trute et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, the scores of fathers seem to be less negative than the scores of mothers. Several topics were indicated as substantially negative or positive by the majority of both parents. The majority of parents indicated that raising a child with PIMD helped them understand what should be valued in life. The majority of parents also indicated that family members became more aware of other people’s needs and the challenges of living with disability. Negatively appraised items mostly concerned time use (extraordinary demands on time, reduction of time with friends, and disruption in habits), but were also material in nature, such as the negative impact on finances. This last negative impact corresponds with a study by Dobson and Middleton (Citation1998), who found that the costs of raising a child with severe disabilities are three times as high as those of raising a typically developing child. Parents’ negative appraisal of the extraordinary demands on their time corresponds with previous research showing that parents spend significantly more time on care tasks compared to parents raising typically developing children (Luijkx et al., Citation2017). Their free time, on the other hand, was substantially limited compared to parents raising typically developing children. The negative appraisal of items concerning time use indicates that families need substantial support to make demands less onerous, especially since increased demands on the time of parents are not expected to decrease as the child grows older (McCann, Bull, & Winzenberg, Citation2012).

Several methodological issues need to be considered to interpret the results in this study. First, using a convenience sample of exclusively Caucasian, two-parent families of children with PIMD living at home in the Netherlands, limits the generalisability of the results. Thereby, for theoretical reasons (gender differences, Crowley & Taylor, Citation1994; Trute et al., Citation2007) and methodological reasons (mothers and fathers were related in the above mentioned study), mothers and fathers were analysed separately. This resulted in a sample size which was too small to allow us to examine the relationship between the characteristics of the parents or children and the parents’ appraisals, although previous research has shown that differences in impact might also be related to the age of the child (Trute et al., Citation2007) or social and cultural diversity (Seligman & Darling, Citation2009). Therefore, future research should look into the relation between family and child characteristics and parental appraisals.

The results suggest that fathers appraise the impact of raising a child with PIMD less negative than mothers. This difference can be related to the division of roles in more traditionally organised families (fathers as breadwinners and mothers as primary carers or working part time), which this study reflects. Previous research has also shown that the mothers of children with ID show higher levels of stress and depression than their spouses (Beckman, Citation1991). Being responsible for daily care tasks can be demanding on mothers and might result in different support needs than fathers. More research into this topic is needed to gain a better understanding of the relationship between gender, family role, and the impact of childhood disability on family life. In addition, tracking parental appraisals over time may provide a better understanding of how the positive and negative impact develop or change. Transition periods, such as the transition from adolescence to adulthood, have been identified as challenging and stressful periods for the parents of children with severe ID (Neece, Kraemer, & Blacher, Citation2009).

Although the co-occurrence of both positive and negative impact on family life corresponds with previous research (Guyard et al., Citation2012; Pugh, Citation2004; Trute et al., Citation2007), in our sample parents expressed more distinct positive and negative appraisals of the impact of children with PIMD on their family lives compared to the parents in previous studies (Guyard et al., Citation2012; Pugh, Citation2004; Trute et al., Citation2007). Parents of children with PIMD might more strongly be positively reframing their child’s disability as a coping strategy to manage the negative aspects they experience (Thompson, Hiebert-Murphy, & Trute, Citation2013). Positive appraisals may be important in helping parents continue their care tasks over a long period (Folkman & Moskowitz, Citation2000), especially in parents of children with PIMD. Their substantial negative appraisal of the impact on family life combined with the extreme time burden (Luijkx et al., Citation2017) calls for support tailored to the needs and wishes of families with children with PIMD and to promote optimal family quality of life.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Beckman, P. J. (1991). Comparison of mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of the effect of young children with and without disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 95, 585–595.

- Blacher, J., Baker, B., & Berkovits, L. (2013). Family perspectives on child intellectual disability: Views from the sunny side of the street. In M. L. Wehmeyer (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology and disability (pp. 166–181). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Crowley, S. L., & Taylor, M. J. (1994). Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of family functioning in families having children with disabilities. Early Education and Development, 5, 213–225. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed0503_3

- Davis, K., & Gavidia-Payne, S. (2009). The impact of child, family, and professional support characteristics on the quality of life in families of young children with disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 34, 153–162. doi: 10.1080/13668250902874608

- Dobson, B., & Middleton, S. (1998). Paying to care: The cost of childhood disability. York: York Publishing Services.

- Eliasson, A. C., Krumlinde-Sundholm, L., Rösblad, B., Beckung, E., Arner, M., Öhrvall, A. M., & Rosenbaum, P. (2006). The manual ability classification system (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 48, 549–554. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206001162

- Ethics Committee Pedagogical and Educational Sciences. (2012). Ethiek reglement. Commissie ethiek afdeling PEDOK [Ethics code. Ethics committee PEDOK]. Retrieved from http://www.rug.nl/gmw/pedagogy-and-educational-sciences/research/ethical-committee/criteria-submit

- Folkman, S. (2008). The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21, 3–14. doi: 10.1080/10615800701740457

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55, 647–654. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.647

- Guyard, A., Michelsen, S. I., Arnaud, C., Lyons, A., Cans, C., & Fauconnier, J. (2012). Measuring the concept of impact of childhood disability on parents: Validation of a multidimensional measurement in a cerebral palsy population. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 1594–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.03.029

- Hastings, R. P., & Taunt, H. M. (2002). Positive perceptions in families of children with developmental disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 107, 116–127. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0116:PPIFOC>2.0.CO;2

- Luijkx, J., Van der Putten, A. A. J., & Vlaskamp, C. (2017). Time use of parents raising children with severe or profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. doi: 10.1111/cch.12446

- McCann, D., Bull, R., & Winzenberg, T. (2012). The daily patterns of time use for parents of children with complex needs: A systematic review. Journal of Child Health Care, 16, 1–27. doi: 10.1177/1367493511420186

- Mencap. (2001). No ordinary life: The support needs of families caring for children and adults with profound and multiple disabilities. London: Royal Society for Mentally Handicapped Children and Adults.

- Nakken, H., & Vlaskamp, C. (2007). A need for a taxonomy for profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 4, 83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-1130.2007.00104.x

- Neece, C. L., Kraemer, B. R., & Blacher, J. (2009). Transition satisfaction and family well being among parents of young adults with severe intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 47, 31–43. doi: 10.1352/2009.47:31-43

- Palisano, R., Rosenbaum, P., Walter, S., Russell, D., Wood, E., & Galuppi, B. (1997). Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 39, 214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x

- Pugh, G. A. (2004). Parenting styles, maternal efficacy, and impact of a childhood disability on the family in mothers of children with disabilities. Retrieved from https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/pugh_gwendolyn_a_200412_ms.pdf

- Seligman, M., & Darling, R. B. (2009). Ordinary families, special children: A systems approach to childhood disability. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Tadema, A. C., & Vlaskamp, C. (2010). The time and effort in taking care for children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: A study on care load and support. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2009.00561.x

- Thompson, S., Hiebert-Murphy, D., & Trute, B. (2013). Parental perceptions of family adjustment in childhood developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 17, 24–37. doi: 10.1177/1744629512472618

- Trute, B., & Hiebert-Murphy, D. (2005). Predicting family adjustment and parenting stress in childhood disability services using brief assessment tools. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 30, 217–225. doi: 10.1080/13668250500349441

- Trute, B., Hiebert-Murphy, D., & Levine, K. (2007). Parental appraisal of the family impact of childhood developmental disability: Times of sadness and times of joy. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 32, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/13668250601146753

- Van Timmeren, E. A., Van der Putten, A. A. J., Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H. M. J., Schans, C. P., & Waninge, A. (2016). Prevalence of reported physical health problems in people with severe or profound intellectual and motor disabilities: A cross-sectional study of medical records and care plans. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60, 1109–1118. doi: 10.1111/jir.12298