ABSTRACT

Background: Organisational and service level factors are identified as influencing the implementation of Active Support. The aim was to explore differences in organisational leadership and structures to identify potential relationships between these factors and the quality of Active Support in supported accommodation services.

Method: Fourteen organisations participated in this mixed methods study, which generated data from interviews with senior leaders, document reviews and observations of the quality of Active Support.

Results: Qualitative analyses revealed three conceptual categories: senior leaders in organisations where at least 71% of services delivered good Active Support prioritised practice; understood Active Support; and strongly supported practice leadership. In these organisations practice leadership was structured close to everyday service delivery, and as part of frontline management.

Conclusions: Patterns of coherent values, priorities and actions about practice demonstrated by senior leaders were associated with successful implementation of Active Support, rather than documented values in organisational policy or procedures.

Small supported accommodation services dispersed throughout communities support a better quality of life for people with intellectual disabilities than larger scale institutional or cluster type accommodation services (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2012). Nevertheless, the quality of life of service users across supported accommodation services (services) is variable, suggesting the model itself is necessary but not sufficient in supporting a good life for people with intellectual disabilities (Bigby, Bould, & Beadle-Brown, Citation2019). In a realist review of propositions about variables influencing outcomes in services, Bigby and Beadle-Brown (Citation2018) found the strongest evidence was in respect of the severity of an individual’s impairment and staff practices that reflect Active Support. Active Support is a support practice whereby staff use an enabling relationship to facilitate the engagement of people with intellectual disabilities in meaningful activities and social relationships (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2012). Evidence about the impact of its use on service users was explored in a systematic review of 20 papers and meta-analysis of the 14 studies reported in these undertaken by Flynn et al. (Citation2018). These authors concluded that consistent use by staff of Active Support leads to “significant increases in the amount of time residents spent engaged in all types of activities at home” (p. 994). Activity and relationships have been shown to be particularly important vehicles by which many aspects of quality of life are achieved (Risley, Citation1996; Saunders & Spradlin, Citation1991). Whilst Active Support is unlikely to be a panacea for ensuring all aspects of a good quality of life for people in services, it serves as an important indicator both of the quality of staff support and, thus, the likelihood of good service user outcomes.

Active Support has been widely adopted by organisations in the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia, but has proved difficult to implement and embed in services (e.g., Mansell, Beadle-Brown, & Bigby, Citation2013). For example, studies using similar observational methods and completion of a measure of Active Support have demonstrated its variable quality, both over time and across services, in organisations that have adopted this practice (Bigby et al., Citation2019; Mansell et al., Citation2013).

There is evidence that difficulties in successfully implementing evidence-based practices, such as Active Support, are common across the health and human services sectors, indeed, implementation science has developed as a new field of study to understand how and why implementation succeeds or fails in organisations (Bertram, Blase, & Fixsen, Citation2015). Studies of implementation draw from disciplines of education, psychology, sociology, organisational theory and management (Nilsen, Citation2015). Much of this work is underpinned by systems theory, which points to the influence of multiple and interacting factors at differing levels within organisations and external environments (Handy, Citation1993). For example, determinant frameworks propose facilitators and barriers to implementation, and although the terms and empirical nature of domains differ in the literature, Nilsen (Citation2015) suggested five as the most commonly identified: (a) characteristics of the intervention, the staff, patients or clients; (b) organisational context, such as readiness, culture and leadership, and facilitating strategies (Nilsen, Citation2015). Taking a different approach, Bertram et al. (Citation2015) proposed three primary drivers of implementation: competency, organisational, and leadership. In particular, consistent across implementation studies has been an emphasis on the significance of organisational context, such as culture, climate, structure and leadership, both at the front line and senior levels (Bäck, von Thiele Schwarz, Hasson, & Richter, Citation2019; Birken, Lee, & Weiner, Citation2012; Moullin, Ehrhart, & Aarons, Citation2018). Managerial leadership, for example, creates “a vision for working in accordance with evidence-based methods, role modelling, encouragement, guidance, information sharing, promotion of strong research values and alterations to quality auditing systems” (Gifford, Davies, Edwards, Griffin, & Lybanon, 2007 cited in Mosson, Hasson, Wallin, & von Thiele Schwarz, Citation2017, p. 545).

The models used by disability researchers proposing domains influencing service outcomes (Clement & Bigby, Citation2010), and many of the propositions in the five domain clusters reviewed by Bigby and Beadle-Brown (Citation2018) resemble those found in the implementation literature and, similarly, originate in psychological or organisational theories. Nevertheless, there is a dearth of empirical evidence about what supports the implementation of or is associated with good levels of Active Support. In many respects, this reflects the limited body of research about senior leadership and the organisational context of disability service organisations. Research about implementation of Active Support has focused primarily at the level of individual service users, such as adaptative behaviour, or the service level, whereby variables, such as number of residents, characteristics and grouping; staff culture, skills, training and attitudes; and strength of front line management or practice leadership have been explored and are specific to each service. Flynn et al. (Citation2018) found tentative evidence from a synthesis of 10 studies about experiences of implementing Active Support for the positive effect of combined classroom and in–situ staff training, services with relatively low staff–to–service user ratios and larger services (to a maximum of six service users), and management processes, such as team meetings. Lending greater support to findings of earlier research, Bigby, Bould, Iacono, Kavangh, and Beadle-Brown (Citation2019) and Bould, Bigby, Iacono, and Beadle-Brown (Citation2019) recently demonstrated the positive influence of strong frontline practice leadership in services on implementation of Active Support leadership.

Organisational level characteristics are those common to all or particular types of services in an organisation, and form the context in which frontline managers and practice leaders work and staff are employed. They include operating procedures, internal managerial structures for organising or monitoring practice, job descriptions, allocation of resources at the service level for funding staff meetings, structures for delivering practice leadership, expectations about frequency and nature of supervision, and the culture or priorities of senior managers. Bigby and Beadle-Brown (Citation2018) noted the limited research about these features and Flynn et al. (Citation2018), in their review, found only weak evidence for the influence of organisational leadership in disability services on Active Support. In a small study, on the basis of qualitative interviews with staff, Qian, Tichá, and Stancliffe (Citation2017) identified a lack of support from the higher levels of the organisation, and absence of policies and structures for implementing Active Support together with an overall lack of organisational readiness as barriers. These findings support the argument of Mansell and Beadle-Brown (Citation2012), drawing on practice wisdom about the significance of commitment from senior managers to successful implementation of Active Support.

As Qian et al. (Citation2017) suggested, there is a need to develop consistent conceptualisations of organisational features and management practices relevant to services in the disability sector in order to operationalise and measure the influence of these contextual factors on implementation of Active Support. Importantly, Qian et al. identified the influence of factors external to organisations that have been studied rarely, such as sector pay conditions, as barriers to the implementation of Active Support in the United States (US) context.

The present study draws on a subset of data from an Australian longitudinal study of Active Support that commenced in 2009. The design had some elements of an action research study, as one of the purposes was to support organisations to embed good quality Active Support through providing annual feedback on staff performance, thereby facilitating exchange of information amongst senior managers, and offering fee-for-service training. However, the study was predominantly quantitative: its size meant researchers could not engage in any depth with each organisation in the cycles of reflection, observation, planning, and activities associated with action research, and the data collection methods were largely consistent throughout the study (McNiff, Citation2013). The design of the study was based on its primary purpose of understanding the individual, service and organisational level factors associated with good Active Support and, thus, the factors that organisations should concentrate on in implementing and embedding Active Support in services.

The aim of the present study was to conceptualise and categorise features of senior organisational leadership and structures for organising practice (referred to as leadership and structures) to enable further investigation of predictors of good Active Support. Research questions were: (1) What are the features of the leadership and structures in participating organisations; (2) How do features of leadership and structures differ across organisations; and (3) Are there patterns indicative of a relationship between leadership and structures and the implementation of good Active Support.

Method

Design

This was a mixed method study. Data sources were semi-structured interviews with senior organisational leaders, organisational documents, and structured observations of the support received by service users, which was used to complete a scale of the quality of Active Support. Textual data from the interviews and documents were analysed qualitatively; rating scale data were analysed quantitively. Data were collected from February 2017 to January 2018, except for data from the first of the two semi-structured interviews, which were collected when each organisation joined the study between 2009 and 2016.

Ethical approval

The study received approval from the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee. Consent was obtained from all staff and service user participants. For those service users without capacity to consent about their involvement, consent was given by a person who usually made decisions for them, typically a parent or senior staff member of the service. When researchers visited services, they continually assessed the assent of service users, and were prepared to leave the service if it became clear by the behaviour of any service users that their presence was not welcome.

Participants and settings

Fourteen organisations participated in the study. They differed in size (6 had an annual turnover >$50 million, 10 managed >10 services), scope (5 provided services for groups other than people with intellectual disabilities), location (in 5 different Australian states) and time since first adopting Active Support (from 1 to 14 years). Service users with intellectual disabilities and senior leaders drawn from these 14 participating organisations were the two primary participant groups. A representative sample of 253 service users, based on socio-demographic characteristics, adaptive behaviour and additional impairments, were selected from the total sample (1112) from the 272 services managed by 14 organisations. Comparisons across selected and non-selected samples were non-significant (Mann–Whitney U and chi-square) for these attributes (). The second group of participants were 18 senior organisational leaders selected for being the most senior managers responsible for leading Active Support implementation who agreed to be interviewed. All were part of their organisation’s executive group, although their titles and seniority levels varied.

Table 1. Comparison of the characteristics of the selected and non–selected service user samples.

Methods of data generation

Quantitative

The Active Support Measure (ASM) (Mansell, Elliott, & Beadle-Brown, Citation2005) was used to determine the quality of Active Support received by each service user. It has 15 items concerning staff skill in delivering Active Support. A scale of 0 (poor, inconsistent) to 3 (good, consistent) is used to rate each item. The maximum score is 45, unless two items about challenging behaviours have not been observed (maximum = 39). Scores are converted to percentages, with 66.66 considered indicative of good Active Support (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2012). Four observers, including the second author, administered the ASM. Across observers, average agreement was 87% (range 69–100%, n = 26), and average Kappa was .73 (range 0.525–1.00). Despite low agreement for some items, paired T-Tests showed no significant differences for overall score agreement across observers, t(25) = 1.125, p = .271.

Qualitative

Two semi-structured interviews were conducted with one or a group of senior leaders in each organisation. The first interview was conducted when the organisation joined the study and sought leaders’ views on implementing Active Support, exploring the reasons for its adoption, strategies to embed it, the organisation of practice leadership and challenges experienced. From the outset of the study, both for data collection (not reported in this paper) and discussion with organisational staff, the researchers used the five key elements set out by Beadle-Brown et al. (Citation2014) to define practice leadership: an overall focus on the quality of life of the people supported; allocating and organising staff to provide the support people need; coaching, observing, modelling and giving feedback to shape up the quality of staff support; reviewing the quality of support with individual staff in supervision; and reviewing team performance in team meetings. During interviews, the meaning of practice leadership using this definition was clarified if there was any uncertainty. A second interview was conducted during 2017 to capture organisational changes since commencement in the study, and perspectives of leaders and nature of structures that coincided with the time that the data on the quality of Active Support reported in this paper were collected. The interview explored participants’ reflections about organisational success with Active Support, further strategies used to embed it, facilitators and barriers experienced, and any changes of note in the organisation since the first interview (2–8 years previously). The qualitative data generated from the interviews were constructed through interaction between the interviewer and participants, taking the form of personal perceptions about strategies to embed Active Support, the success of the organisation and its progress with it, as well as data of a more factual nature describing structures and processes. A different type of qualitative data was the text of documents, including the most recent annual report, position descriptions for support workers, training materials, and documents describing practice.

Procedure

For each organisation, a deidentified audit database containing the characteristics of each service and service user had been compiled when the organisation joined the study and updated annually. The representative sample of service users was selected from the database. Information and consent forms were sent to each organisation to be distributed to selected service users. For the study to proceed in any service, at least one service users’ consent was required. Once received, a researcher conducted a 2-hour observation in each service, then completed the ASM for each consenting service user.

When each organisation joined the study, the senior staff member involved in the negotiation was invited to nominate a senior leader to participate in an interview. This invitation was again extended when the annual collection of quantitative data commenced in February 2017. Interviews were conducted by the first author and lasted from 45 to 90 min. They were audio recorded with permission and subsequently transcribed verbatim.

Organisations were sent a list of document types when data collection commenced in February 2017. They were invited to select the most recent of each type and send either electronic copies by email or hard copies by post to the research team.

Analysis

Quantitative

For each service user, the percentage of the maximum possible score on the ASM was calculated. The percentage of service users in each service who received good Active Support was calculated, and then the percentage of services in each organisation in which 51% or more service users received good Active Support was determined.

Qualitative

The constructed data from the senior staff interviews were analysed through an inductive interpretative analysis using grounded theory coding methods and constant comparative approach (Charmaz, Citation2006). This analytical approach, underpinned by symbolic interactionism (Blumer, Citation1969), allowed extraction of the meanings people gave to their actions and context. Exploration of these data without predefined categories allowed patterns across the whole data set to emerge (Charmaz, Citation2006). The first author led the analysis, initially closely reading the transcripts repeatedly and then moving through a process of data driven open coding to identify emergent categories about senior managers’ perceptions of embedding Active Support. Using an iterative process of comparing and contrasting open coding, the codes became increasingly focused as they were collapsed together into more conceptual and abstract categories until one overarching conceptual category, senior leaders focus on practice and Active Support, and four subcategories emerged.

A less interpretative content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) was used to code the more factual textual interview data about the way practice leadership was structured. A similar process of open and then more focused coding was used to generate and refine subcategories, until an overarching category, organisation of practice leadership, and two subcategories emerged. Finally, similar methods of open and focused coding were used to code document data that described practice expectations of direct support workers, until a conceptual category, coherence of documented practice descriptions, and two subcategories emerged.

Next, the data were disaggregated by organisation and reviewed to identify categories and subcategories dominant or absent in each organisation. Drawing on Ragin’s (Citation1987) comparative method, this information was entered into a matrix (see ). Also included in the matrix was the percentage of services (and service users) in each organisation in which the majority of service users (51%+) received good Active Support. The data matrix was visually inspected to identify any patterns between presence of subcategories and presence of good Active Support.

Table 2. Matrix of categories and subcategories about organisational leadership and structures and percentage of services with good Active Support by organisation.

Trustworthiness

Issues of rigour, such as those set out by Charmaz (Citation2006), which include credibility, originality, resonance and usefulness were addressed. The first author used memo writing to create an audit trail of emergent codes and coding decisions. A process of code refinement comprised discussion between the first and second author, who also read the transcripts, discussion about differences in interpretation, with codes initially refined to achieve consensus, then finally refined through sharing and discussion amongst all four authors. To check for resonance and usefulness, the findings were presented at forums and conferences that included experienced service providers. Illustrative quotes from participants, descriptions of structures and document contents have been used to demonstrate the grounding of the results in the data.

All identifying information was disguised to preserve individual and organisation confidentiality. A numeric identifier has been used for each organisation.

Results

Quantitative results

Quality of Active Support

shows the results ordered by highest to lowest percentage of services in an organisation in which at least 51% of service users received good Active Support. As shows, the range was 29–100%; for six organisations, more than two thirds of services were delivering good Active Support to the majority of service users.

Qualitative results

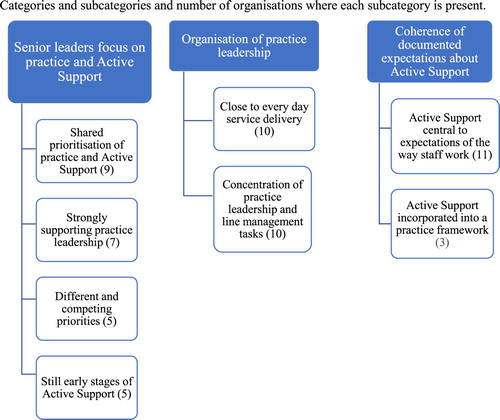

shows the three conceptual categories that captured features of leadership and structures and the subcategories associated with of each of these. They are described in detail using illustrative quotes in the sections that follow.

Figure 1. Categories and subcategories and number of organisations where each subcategory is present.

Senior leaders focus on practice and Active Support

This category captured perspectives of interviewees about the importance they and other leaders accorded to practice in the organisation, both in general, and in particular to Active Support. Perspectives fell into four non-exclusive subcategories: (1) shared prioritisation of practice and Active Support; (2) strongly supporting practice leadership; (3) different and competing priorities; and (4) still early stages of Active Support.

Shared prioritisation of practice and Active Support – ‘practice is really, really important’: Nine senior leaders shared a priority for practice and Active Support with other leaders in their organisation, all of whom recognised the significance of frontline staff practice to achieving organisational aims. They said, for example,

We manage and develop on the basis of practice of trying to put theory or well researched stuff into action … continuing to put energy into the area of practice to maintain the quality. (1)

… we are focused so much on our practices and the standard of our practice because without having good quality standards of practice, we don’t see good client outcome, the two go hand in hand. (13)

These leaders understood Active Support as central to good practice. Their and other senior leader’s commitment was demonstrated through investing resources in mechanisms to lead Active Support, profiling practice in organisational priorities, diffusing language about practice through the organisation, and continuously reflecting on progress and searching for strategies for improvement.

They recognised tensions middle managers faced in being practice focused, and the potential for diversion by operational responsibilities. A solution was to create new senior or middle level positions, without administrative responsibilities, to lead and sustain good practice. Organisation 8, for example, had created a senior practice leadership role about, “being able to focus obviously on practice … for a far more keenly sharpened focus on person-centred Active Support.” Organisation 3 had created a similar senior position, which the interviewee commented, had injected a strong set of practice skills into the organisation and had positively impacted through “support for the program manager and practice leaders.” Another had created a less senior position of practice adviser to “put Active Support more on the table than it ever had been.” This organisation was preparing to invest more in such positions to take account of the occupant “being spread a little bit too thin … as the number of services grows” (7).

Investment in organisation–wide positions to lead practice did not abrogate what these leaders perceived as the shared responsibility for practice amongst those in senior positions, which also meant knowing and being able to recognise good Active Support. They said for example,

… our practice leaders and our practice managers as well as all of the leadership team and then my whole team as a service improvement team are very well versed in Active Support. (13)

The model of leadership is not top down. It’s representing each part of the organisation … that’s really important in terms of trying to affect that cultural change, and embedding the concepts [of Active Support] within the organisation. (14)

Active Support is our whole approach, not just an add on … you come here any day and you will see that … you can ask anyone in [our] organisation, “Do we do this?” They’ll say, “Yes.” … we don’t always all the time, but people do know what it is. (7)

… we’re building that consistency … that shared language and the consistent approach … everybody’s on the same page. (8)

I wanted it to be embraced by all, from singing from one hymn sheet, not from ten varied ones. (13)

Finally, these leaders were enthusiastic and strongly reflective. Rather than disheartened or complacent about Active Support progress, they maintained momentum by continuously seeking new strategies to make a difference, even if this meant exposing their limitations to researchers or other organisations,

… even though we had been committed and said that we used Active Support … we just knew that we weren’t getting traction … We didn’t know what we didn’t know, and participating in this research allowed us to hone in on very clear strategies to actually embed Active Support. (8)

… we knew we were slipping and not focusing on the practice of our staff sufficiently … We don’t learn by mistakes, we learn by reflecting on mistakes. (2)

I didn’t save any money because I was able to redirect those financial resources to increasing the mentoring and observation time of practice leaders … specifically, on roster for mentoring rather than being an active worker. (3)

Several interviewees had encouraged operational managers to monitor the performance of practice leaders more actively. The leader of organisation 1 praised the qualities of a middle manager, saying, “[manager] has done a terrific job focusing on practice, supporting, mentoring, the practice leaders, really looking at outcomes, what’s happening.” Others said of middle managers,

[practice leadership] needs to be at the top of their thoughts … making sure that’s how they are supervising their staff. (8)

… [they] need to ensure continuous improvement in their team’s delivery of person centred active support. (3)

… in our induction and our training [we might have] taken some focus off the importance of engagement and interaction … the basics of Active Support are not coming through … . (4)

… we’re working on Active Support but we’ve got a lot of those other fundamentals we have to get in place in order to have people with the right skills and capabilities, and people who are accountable for what they are doing and delivering what we need them to deliver. (10)

The implications of losing a previously shared commitment to practice were felt strongly by several leaders. Talking about how the focus on Active Support had stagnated one said,

… I’m flying the flag a bit solo at the moment, to be honest, in terms of the links back to that approach [Active Support]. That really deeper, philosophical practice training has definitely been diluted … probably a heavier focus towards our compliance obligations … the language of person–centred practice and Active Support is almost evaporated from the business … . (5)

A very similar loss of a shared focus was described by another leader, when staffing changes meant the deep practice understanding previously held by senior managers was lost,

[manager] is not necessarily trying to take away that focus of Active Support, not at all. I think it’s just all this other stuff that’s happening, which is time–consuming and stressful and that’s kind of detracting from it a bit. (6)

The actual impact has been really, really extreme and it just continually drags people that way, in terms of the focus of their job, just to get these back–office systems functional … just the finances, the transactional nature of the NDIS. (6)

… the enormous amount of work transforming every part of [organisation] as we transition to the NDIS … to develop new information systems … a customer management system, our incident reporting system, our systems for recording and managing staff performance issues, our recruitment, and our service delivery and management. Attention to risk management as well … that has meant that we haven’t been able to implement what we might have liked. (10)

We’ve got a plan, we know where we’re going … it’s just the pace … I think practice leadership, having a practice framework is something that I would like to see. I don’t think that where we’re far enough down the track at all in that regard … we talk about Active Support … But I don’t think we’ve set that up enough. (9)

It [training] talks about human rights and respect and we go through the engagement and how people support people. So, lots of conversations about it … my thinking is do we need to have it more targeted towards Active Support as a role and function. (4)

one of the challenges is to dedicate adequate time to that [mentoring coaching] when things are complex … it’s easy to get swamped with administrative tasks and the administrative burden … the practice performance stuff it’s still a challenge for us … we’re trying to get to a point in looking at the structure … to make it more of a proactive sort of a role … they’re probably reactive at the moment. (4)

It’s our opportunity to engage in some really strong cultural change, and to embed that capacity for those sorts of practices, and the training that goes with the practices within our organisation. (14)

We plan to implement it across all services, so it becomes a core part of our practice and our model … but it’s a work in progress … I don’t think there’s anything necessarily getting in the way, it’s just that the implementation and development of it across a large organisation, it’s still relatively new, so we’re just progressing and building the knowledge and the confidence. (11)

… [practice leaders] are more doing the troubleshooting rather than the balanced oversight of all houses. I think they’re more brought in where there might be some issues … working with teams maybe around behavioural strategies or interventions … . (9)

… we recently started the process of re–looking at the job descriptions for our team leaders, and moving out some of the administrative based functions, and the rostering functions, and bringing that back into a central pool. (14)

Organisation of practice leadership

Practice leadership as defined in this study is delivered at the front line, at the service level. Elsewhere we have reported its variable quality between services within organisations (Bigby et al., Citation2019). However, the way that practice leadership is structured is generally similar across services within an organisation, reflecting decisions of senior leaders. Since the study began, in search of greater effectiveness and cost efficiency, some organisations had restructured the way practice leadership was organised. Some had moved away from a traditional model in which there is a supervisor in each service, who worked shifts, with administrative responsibilities and some non–contact time allocated for other practice leadership tasks (Clement & Bigby, Citation2010). The analysis identified more than five different ways of organising practice leadership. These differed along two key dimensions, which were captured in the following two subcategories.

Closeness of practice leadership to everyday service delivery: In 10 organisations, the position with responsibility for all or most of practice leadership tasks was close to frontline service delivery. The occupant had both regular planned and incidental contact with support staff and service users. For example, a team leader or practice leader position had responsibility for leading practice, but not necessarily all the administrative tasks in one, or, at most, two services. The rationale for this type of structure was explained by one leader who had recently restructured practice leadership across the organisation,

We’ve had team leaders who have worked across three houses minimum. In some instances, there may have even been four. But we definitely realise that the optimum number is two houses, which gives that team leader the opportunity in theory to be able to get out to their locations and be more present in the houses. (8)

Concentration of frontline management and practice leadership: In 10 organisations, responsibility for all five elements of practice leadership and first line management of support staff in a service were concentrated in one position. Organising practice leadership in this way was similar to the traditional model of one service – one supervisor, although in many cases the position of supervisor or practice leader managed more than one house. As one senior leader said of the recently renamed practice leader positions in his organisation,

Their span of responsibility is primarily around the people they support and developing their teams. And that’s everything from goal review and monitoring, behaviour support plans, so drafting and driving the documents and systems and culture that are behind our increasing support of the people who live in the houses. (3)

Coherence of documented expectations about Active Support

This conceptual category represented the clarity with which expectations about staff use of Active Support were encapsulated in organisational documents. Two subcategories captured how practice expectations were described, serving as indicators of a coherent practice approach and clear messaging about Active Support: (1) Active Support central to expectations of the way staff work, and (2) Active Support incorporated into a practice framework.

Active Support central to expectations of the way staff work. Position descriptions in 11 organisations articulated an expectation that Active Support was a core to the work of support staff, by either describing core tasks of support work or naming Active Support. For example,

… the role provides a quality service of Person Centred Active Support to achieve meaningful community inclusion, choice, personal growth and living skills to people with a disability … Provide the right amount of assistance to support clients to achieve independence in their daily living. (13)

The people we support and their families are at the centre of decision–making, with support tailored to meet their individual needs and goals … we have adopted Person Centred Active Support as the framework for how we assist and support people to participate and exercise greater control and choice in their daily. (6)

The clarity of the practice frameworks in these organisations contrasted with the documentation in others, many of which did not include a practice framework. Descriptions of what they would deliver were pitched as highly abstracted values or principles.

Comparing patterns of leadership and structures with the quality of Active Support

shows a matrix mapping the results of the qualitative analysis, in terms of the presence or absences of subcategories, for each organisation against the quantitative data about percentage of services with good Active Support. The table has been organised according to having most to least services achieving good levels of Active Support for the majority of service users. A visual inspection of the eight subcategories revealed a key pattern: in organisations with 71% or more services with good Active Support, subcategories 1.1, 1.2, 2.1 and 2.2, were present, and, with the exception of Organisation 3, subcategory 3.2 was also present. Notably, no other organisations had all of the four subcategories (1.1, 1.2, 2.1 and 2.2) present. A weaker pattern was evident for organisations with 57% or more services with good Active Support: all had at least five subcategories present, but so did organisation 11 which only had 29% of services with good Active Support. Moreover, there was no consistent pattern to the subcategories present across these organisations. The pattern in suggests that the combination, in an organisation, of shared prioritisation of practice and Active Support (1.1), and strong support for practice leadership by senior managers (1.2), the organisation of practice leadership close to every day service delivery (2.1), and concentrated with frontline management (2.2), are potentially associated with good Active Support in its services.

Discussion

Three conceptual features of senior leadership and organisation-wide structures and processes were identified: (1) senior leaders’ focus on practice and Active Support; (2) organisation of practice leadership; and (3) coherence of documented expectations about Active Support. The features captured in eight subcategories of these three features differed across organisations. The pattern in suggests that the combination of shared prioritisation of practice and Active Support, strong support for practice leadership by senior managers, the organisation of practice leadership close to every-day service delivery and concentration in one position with frontline management are associated with good Active Support.

Reflecting the influence of implementation science, the study focused on senior leaders and the organisational context in which Active Support is implemented. Its findings include conceptualisation of some features of leadership and contextual factors in disability service organisations, furthering the opportunity to assess or measure these in the future as proposed by Qian et al. (Citation2017). Overall these findings reflect some of the features associated with coherence within organisations, proposed as significant to good service user quality of life, for which there is scant evidence (Bigby & Beadle-Brown, Citation2018). In the present study, it was coherence of the values articulated by senior leaders, and their priorities and actions about practice that appeared to be associated with the implementation of good Active Support, rather than documented values in organisational policy or procedures. The senior leadership in nine organisations shared practice as an organisational priority, reflecting the type of commitment by senior leaders necessary for implementation of evidence-based practice found in studies of other health and human services sectors (Bertram et al., Citation2015). In contrast, in the other five organisations, senior leaders regarded practice as only one of many competing priorities, resembling to some extent, the absence of support by organisations for the implementation of Active Support identified by Qian et al. (Citation2017). These qualitive data, which also suggest a change in commitment to practice by senior leaders in some organisations since the study begun, are indicative of the fragility of prioritising practice over time by senior leaders. The data may also illustrate the impact on implementation of external factors; identified by Qian et al. (Citation2017) as labour conditions, but in this study the Australian disability reform, NDIS.

The difficulty in maintaining a shared priority about practice and Active Support is similar (and perhaps reflective of) the fragility of the quality of Active Support in organisations, and difficulties in maintaining a high proportion of staff trained in this practice (Bigby et al., Citation2019; Qian, Larson, Tichá, Stancliffe, & Pettingell, Citation2019). These findings demonstrate the significance of ensuring organisational leaders understand and prioritise practice rather than allocating responsibility for practice quality to one senior position or division. They raise warning flags for senior leaders about the ease with which they, and their organisation can be diverted from ends to means: that is, from the core business of delivering quality support to concentrating on administrative structures and processes, and reporting mechanisms assumed necessary for doing so. These findings resonate with the early results from a study of culture in support services for people with complex needs in Norway (Tøssebro, Citation2018), where a new focus on managerialism shifted attention of supervisory staff from practice to paperwork designed to make them accountable for practice.

The subcategory still in the early stages presents a conundrum. Relying on subjective perceptions of interviewees and unrelated to the actual time since implementation of Active Support, this subcategory was present in organisations that had been implementing Active Support for 1–5 years and absent in others implementing it for similar periods. Differing organisational size, complexity or geographic spread, or turnover of senior staff and loss of corporate memory about practice initiatives may be explanations. Nevertheless, the absence of this subcategory in any of the organisations with more than 71% of services with good Active Support lends some support to a previous finding of a positive association between time since implementation and Active Support quality (Bigby et al., Citation2019; Bould et al., Citation2019). However, it may be that time necessary to implement Active Support is influenced by organisational size and scope, or stability of senior leaders, and, hence, be a poor single indicator.

The findings reflect the potential significance of organisational structures to implementation identified in the literature. They also contribute to understanding more specifically the type of structures needed to deliver strong practice leadership at the service level, which Bigby et al. (Citation2019) and Bould et al. (Citation2019) had identified as promoting good Active Support. The beneficial effects of structuring the tasks of practice leadership close to frontline service delivery and concentrating these tasks in one position were alluded to by interviewees and are found in the practice literature (Ashman, Ockenden, Beadle-Brown, & Mansell, Citation2010). There are, for example, more likely to be opportunities to know the service users in a service well and for informal modelling, coaching and observation sessions to occur if practice leaders spend more time in the services. Knowing service users also helps practice leaders to gain credibility with staff, whilst concentrating practice leadership tasks with frontline management is likely to facilitate more regular feedback and authoritative supervision to staff about all aspects of their practice. This finding, alongside those of Bigby et al. (Citation2019) and Bould et al. (Citation2019) about the influence at the service level of strong practice leadership on quality of Active Support, strengthens the case for attention by organisations to all aspects of practice leadership.

A further aspect of organisational context was reflected in the category coherence of documented expectations about Active Support, derived from analysis of paperwork. Although expectations about using Active Support were present in the support worker job descriptions of most organisations, only a few had either a coherent practice framework or one that incorporated Active Support. The relative absence of this type of documentation suggests support workers may face multiple expectations of their practice, without the means to integrate or prioritise them. However, the pattern in these data about potential factors associated with good Active Support does not support propositions about the importance of coherent paperwork and documenting expectations (Bigby & Beadle-Brown, Citation2018). The apparent insignificance of paperwork to Active Support practice may not be surprising in light of the studies by Quilliam, Bigby, and Douglas (Citation2018) that showed staff seldom read high level organisational documents, manage paperwork to reflect their own practice wisdom and priorities, and, at times, complete paperwork by describing what should have happened rather than what did.

Conclusion

Mansell, Beadle-Brown, Whelton, Beckett, and Hutchinson (Citation2008) suggested that organisational features affecting implementation of Active Support are likely to work in combination, and, hence, are best explored through statistical modelling. Qian et al. (Citation2017) pointed out that these features first require conceptualisation and measurement. A strength of this mixed methods study was the identification of organisational features derived from the qualitative data and combinations of these that are potentially associated with implementation of good Active Support. These organisational features and potential associations found in this study provide the basis for measurement of organisational leadership and structures. In this way, a limitation of this and other studies in failing to quantify organisational features emerging as potentially relevant to implementation of good Active Support could be addressed. A direction for future research, therefore, is to transform the qualitative into quantitative data for use in a multilevel model of factors predicting the quality of Active Support. Such a model could test statistically the influence of items 1.1, 1.2, 2.1 and 2.2 singly or in combination on quality of Active Support. Also important is further exploration of organisational culture, leadership characteristics or other factors that support and sustain a focus on practice by senior leaders, using qualitative case study or action research methods. Further research about effective ways of organising practice leadership is also warranted given the diversity identified in this study. This issue is particularly pertinent at a time in Australia and elsewhere when changes to funding formulae and recognition of the administrative burden on frontline managers (Clement & Bigby, Citation2010) are being recognised.

The purpose of the present study was to provide further insights into organisational factors that require specific attention and resources by disability service organisations and funders in order to achieve good quality Active Support. The patterns identified point to the importance of what might be constructed as a strong culture of support for practice amongst senior leaders of an organisation, combined with structuring practice leadership so that it is close to frontline service delivery and tasks are concentrated and aligned with those of line management. Indeed, coherence of values and actions that prioritise practice appear to be more important than carefully crafted organisational policies and procedures, which are often the focus of quality assurance processes, auditors, funders and regulators. These findings provide pointers for organisations as they redesign delivery of practice leadership to take account of organisational size and externally imposed funding imperatives. They also point to implications for the Australian NDIS in developing appropriate funding levels to support the type of structures and strength of both organisational and frontline practice leadership skills necessary to implement good Active Support practice and, thus, good quality of life for service users.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are extended to the disability services participating in this study, and to research assistants Louise Phillips, Samuel Murray, Emma Caruana, Lincoln Humphreys, Rosa Solá Molina and Andrew Westle for support with data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ashman, B., Ockenden, J., Beadle-Brown, J., & Mansell, J. (2010). Person–centred active support: A handbook. Bristol: Pavillion Publishing.

- Bäck, A., von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hasson, H., & Richter, A. (2019) Aligning perspectives?—comparison of top and middle-level managers’ views on how organization influences implementation of evidence-based practice. The British Journal of Social Work, bcz085. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcz085

- Beadle-Brown, J., Mansell, J., Ashman, B., Ockenden, J., Iles, R., & Whelton, B. (2014). Practice leadership and active support in residential services for people with intellectual disabilities: An exploratory study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58, 838–850. doi: 10.1111/jir.12099

- Bertram, R., Blase, K., & Fixsen, D. (2015). Improving programs and outcomes: Implementation frameworks and organization change. Research on Social Work Practice, 25, 477–487. doi: 10.1177/1049731514537687

- Bigby, C., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2018). Improving quality of life outcomes in supported accommodation for people with intellectual disability: What makes a difference? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31, e182–e200. doi: 10.1111/jar.12291

- Bigby, C., Bould, E., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2019). Implementation of active support over time in Australia. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 44, 161–173. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2017.1353681

- Bigby, C., Bould, E., Iacono, T., Kavangh, S., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2019). Factors that predict good active support in services for people with intellectual disabilities: A multilevel model. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. doi: 10.1111/jar.12675

- Birken, S., Lee, S., & Weiner, B. (2012). Uncovering middle managers’ role in healthcare innovation implementation. Implementation Science, 7, 28. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-28

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bould, E., Bigby, C., Iacono, T., Beadle-Brown, J. (2019). Factors associated with increases over time in the quality of active support in supported accommodation services for people with intellectual disabilities: A multilevel model. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 94. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103477.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

- Clement, T., & Bigby, C. (2010). Group homes for people with intellectual disabilities: Encouraging inclusion and participation. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Flynn, S., Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Hood, K., Toogood, S., & Felce, D. (2018). Effectiveness of active support for adults with intellectual disability in residential settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31, 983–998. doi: 10.1111/jar.12491

- Handy, C. (1993). Understanding organizations (4th ed.). London: Penguin.

- Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

- Mansell, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2012). Active support: Enabling and empowering people with intellectual disabilities. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Mansell, J., Beadle-Brown, J., & Bigby, C. (2013). Implementation of active support in Victoria, Australia: An exploratory study. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 38, 48–58. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2012.753996

- Mansell, J., Beadle-Brown, J., Whelton, R., Beckett, C., & Hutchinson, A. (2008). Effect of service structure and organisation on staff care practices in small community homes for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21, 398–413.

- Mansell, J., Elliott, T. E., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2005). Active support measure (revised). Canterbury: Tizard Centre.

- McNiff, J. (2013). Action research: Principles and practice (3rd Ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Mosson, R., Hasson, H., Wallin, L., & von Thiele Schwarz, U. (2017). Exploring the role of line managers in implementing evidence-based practice in social services and older people care. The British Journal of Social Work, 47, 542–560.

- Moullin, J., Ehrhart, M., & Aarons, G. (2018). Development and testing of the measure of innovation-specific implementation intentions (MISII) using Rasch measurement theory. Implementation Science, 13, 89. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0782-1

- Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models, and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

- Qian, X., Larson, S., Tichá, R., Stancliffe, R., & Pettingell, S. (2019) Active support training, staff assistance, and engagement of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the United States: Randomized controlled trial. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 124, 157–173. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-124.2.157

- Qian, X., Tichá, R., & Stancliffe, R. J. (2017). Contextual factors associated with implementing active support in community group homes in the United States: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 14, 332–340. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12204

- Quilliam, C., Bigby, C., & Douglas, J. (2018). Staff perspectives of paperwork in group homes for people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3, 264–273. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2017.1378315

- Ragin, C. (1987). The comparative method: Moving beyound qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkely: University of Calfornia Press.

- Risley, T. R. (1996). Get a life! Positive behavioral intervention for challenging behaviour through life arrangement and life coaching. In L. K. Koegel, R. L. Koegel, & G. Dunlap (Eds.), Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community (pp. 425–437). Baltimore: Brookes.

- Saunders, R. R., & Spradlin, J. E. (1991). A supported routines approach to active treatment for enhancing independence, competence and self-worth. Behavioral Residential Treatment, 6(1), 11–37.

- Tøssebro, J. (2018). Delivering intensive support services to people with disability and complex support needs in Norway: Findings from a recent study. Paper presented, Living with Disability Research Centre Seminar, October, LaTrobe University, Melbourne.