Abstract

Background: Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have been associated with falls in studies either exclusively or predominantly of women. It is, therefore, less clear if LUTS are risk factors for falls in men.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review of the literature on the association between LUTS and falls, injuries, and fractures in community-dwelling older men. Medline, Embase, and Cinahl were searched for any type of observational study that has been published in a peer-reviewed journal in English language. Studies were excluded if they did not report male-specific data or targeted specific patient populations. Results were summarized qualitatively.

Results: Three prospective cohort studies and six cross-sectional studies were identified. Incontinence, urgency, nocturia, and frequency were consistently shown to have weak to moderate association with falls (the point estimates of odds ratio and relative risk ranged from 1.31 to 1.67) in studies with low risk of bias for confounding. Only frequency was shown to be associated with fractures.

Conclusions: Urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract storage symptoms are associated with falls in community-dwelling older men. The circumstances of falls in men with LUTS need to be investigated to generate hypotheses about what types of interventions may be effective in reducing falls.

Introduction

Falls are common among older people and often result in injuries [Citation1]. A systematic review by Chiarelli et al. [Citation2] showed that lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as incontinence, urgency, and nocturia were associated with falls. Most studies included in the review, however, were exclusively or predominantly of women. The patterns of co-occurrence and severity of LUTS are different between men and women [Citation3]. In addition, there may be gender-related behavioral differences in strategies to manage LUTS which could also influence fall risk. There has not been a systematic review on the association between LUTS and falls that focuses on men and it is, therefore, less clear if LUTS are risk factors for falls in men.

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to determine if LUTS were associated with falls, injuries and fractures in community-dwelling older men. We also examined whether this association was influenced by type and severity of LUTS.

Search strategy and selection criteria

The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42014009354).

Data sources and searches

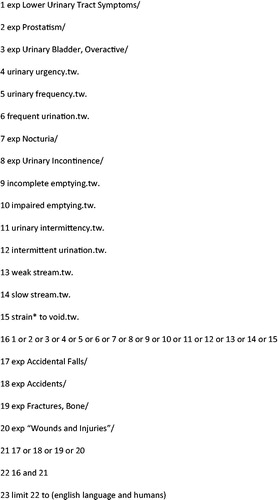

One investigator (NN) carried out a systematic literature search in Medline (1966 to August 2015), Embase (1980 to August 2015), and Cinahl (1982 to August 2015). A search strategy was constructed with the assistance of a medical librarian. Terms for LUTS, such as urgency, frequency, nocturia, and incontinence, were used in combination with terms for falls, injuries, and fractures. The full search strategy for Medline is presented in . In each database, terms were searched as index terms where available or otherwise searched as key words within title and abstract. All the retrieved studies on the association between LUTS and falls regardless of study population were utilized to identify further eligible studies: reference lists were examined and publications that cited these studies were also identified using PubMed.

Study selection

One investigator (NN) scanned titles and abstracts, and evaluated full texts of potentially relevant studies referring to the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria as follows. Studies were considered for inclusion if they (1) included community-dwelling men with a mean age of 60 years and older and (2) determined the associations of LUTS with falls, injuries and fractures. Studies were excluded if they (1) did not report male-specific data, or (2) targeted specific patient populations such as dementia or post-urological procedures. The search was limited to English language but no restriction was set for time of publication. Any type of observational study published in a peer-reviewed journal was included.

Data extraction and quality assessment

One investigator (NN) extracted data about the study characteristics and the estimates of associations. Another investigator (VN) checked the extracted data for accuracy. Results from multivariate analyses, if available, were selected. When estimates of associations were unavailable, unadjusted measures of association were calculated from raw data.

Methodological quality of included studies was assessed by one investigator (NN) using an adaptation of the study quality check list that Stalenhoef et al. used in their systematic review of fall risk factors [Citation4]. Another investigator (VN) verified the quality assessment.

Data synthesis and analysis

Data were synthesized qualitatively structured around each LUTS. Types and severity of LUTS were taken into account where available. Because this is a review of observational studies, meta-analysis was not conducted and we focused on examining possible sources of heterogeneity between studies [Citation5].

Results

Selection of studies

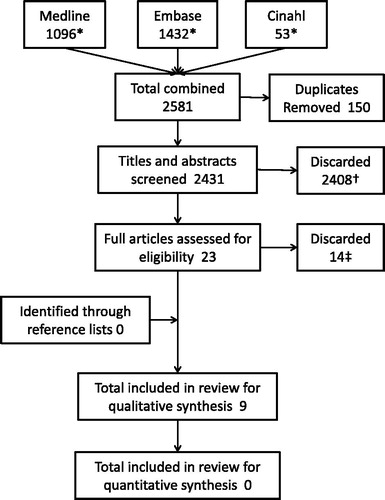

shows the selection process for relevant studies. A search of the databases identified 2431 studies after removing duplicates. Two thousand four hundred and eight were excluded after reviewing titles and abstracts including 19 that were not community-based and 10 that were studies of women. After 23 full texts were retrieved, 14 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria: one included only younger men, nine did not report male-specific data, and four did not examine the association of interest. No additional study was identified from reference lists of retrieved articles. Nine studies that met all the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the review for qualitative synthesis [Citation6–14].

Figure 2. Selection process of relevant studies. *Excluding duplicates within databases. †Reasons for exclusion after screening titles and abstracts include off topic (n = 2362), case report (n = 1), letters to editors or opinion papers (n = 10), not community-based (n = 19), study of women (n = 10), and systematic review (n = 6). ‡Reasons for exclusion after assessing full text include younger participants (n = 1), male-specific data not available (n = 9), did not examine the association (n = 4).

Appraisal of studies

summarizes the characteristics and the results of the included studies. The studies are listed chronologically. Studies by Parsons et al. and Frost et al. were large prospective studies exclusively of men [Citation10,Citation13]. Another study by Nakagawa et al. was also prospective but had a small sample size [Citation11]. The cross-sectional studies by de Rekeneire et al., Asplund et al., and Foley et al. also had large sample size of men [Citation8,Citation9,Citation12]. The study by Parsons et al. looked at all the symptoms in the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) [Citation15] questionnaire individually [Citation10]. The other studies examined only one symptom each. Outcomes included one or more falls (any fall) [Citation6–8,10,12,14], two or more falls (recurrent falls) [Citation10], any fracture [Citation6,Citation11,Citation13], hip fractures [Citation9], and osteoporotic fractures [Citation13]. Observation or recall periods were one year for falls and five years for fractures.

Table 1. Characteristics and results of the included studies.

Methodological quality appraisal of included studies is presented in . Stewart et al., de Rekeneire et al., and Parsons et al. limited participation to healthier or ambulatory community-dwelling men [Citation6,Citation8,Citation10]. Loss to follow-up was not a problem in any of the three prospective studies: Parsons et al. excluded only 1% with incomplete data [Citation10]; and the other two were linkage studies in universal health-care systems which capture nearly all fractures [Citation11,Citation13]. The time frame and frequency of occurrence of LUTS were specified only in the study by Parsons that employed the IPSS [Citation10]. Using this validated questionnaire, occurrence of LUTS was limited to the past month, frequency of the symptoms was taken into account, and also definitions of each LUTS were given. To determine LUTS, no study conducted objective tests such as pad weight test or bladder diary. Five studies collected data through self-administered questionnaires [Citation9,10,12–14], and the other four used face-to-face interviews. The definitions of falls were not clearly stated in four studies [Citation8,Citation10,Citation12,Citation14]. All three prospective studies determined falls and fractures adequately either by close follow-up for falls [Citation10] or by linkage to health-care databases for fractures [Citation11,Citation13]. All the cross-sectional studies relied on recall over the past year for falls and past five years for fractures. All three prospective studies by Parsons et al., Nakagawa et al., and Frost et al. and the cross-sectional studies by Yasumura et al., de Rekeneire et al., and Hedman et al. made more extensive adjustments for potential confounders than for age alone [Citation7,8,10,11,13,14]. We, therefore, considered these six studies to be more robust than the rest as confounding is the most important source of bias in observational studies [Citation16].

Table 2. Quality of included studies.

Study findings

Nocturia

Nocturia was consistently shown to be associated with increased risk of any fall. In Parsons et al.’s study, men who voided four to five times per night were at increased risk of falls relative to men who voided zero or one time (adjusted RR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.08–1.41) [Citation10]. A wide range of fall risk factors were accounted for in this large prospective study. Adjusted OR was 1.63 (95% CI: 1.00–2.68) in Stewart et al.’s study in men who voided at least twice per night compared with men who voided zero or one time [Citation6]. This study only adjusted for age and determined falls retrospectively. Yasumura et al. showed a positive association, but the confidence interval was wide as a majority of the small sample met the nocturia criteria of any nighttime void [Citation7].

Parsons et al. also examined the association of nocturia with recurrent falls which was stronger (adjusted RR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.16–1.74) than with any fall [Citation10].

The risk estimates for any fracture in five years were in opposite directions in the two studies that looked at fractures and not significant in either: adjusted HR was 2.61 (95% CI: 0.76–8.95) in Nakagawa et al.’s prospective study [Citation11], and adjusted OR was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.35–1.34) in Stewart et al.’s cross-sectional study [Citation6] with nocturia defined as two or more voids per night in both studies. The numbers of fractures over five years were limited in both studies (13 in Nakagawa et al.’s and 38 in Stewart et al.’s), resulting in wide confidence intervals.

Asplund et al. reported that the recalled history of hip fractures in past five years increased as number of nighttime voids increases, but adjustment was not made even for age and the information provided did not allow us to calculate OR [Citation9].

Incontinence

In all three cross-sectional studies that examined the association between incontinence and any fall, incontinence was consistently shown to be associated with increased risk of any fall. The risk estimate was the largest in Foley et al.’s study which did not adjust for any potential confounders and defined incontinence as any leakage of urine (unadjusted OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.51–2.29) [Citation12]. The other two studies accounted for a wide range of fall risk factors but did not explicitly define urinary incontinence: adjusted ORs were 1.5 (95% CI: 1.1–2.0) in de Rekeneire et al.’s study [Citation8] and 1.67 (95% CI: 1.13–2.47) in Hedman et al.’s [Citation14].

None of the studies in men determined the association with falls by type or severity of incontinence.

Frequency

The large prospective study by Parsons et al. found frequency, defined as having to void within 2 h since the last void at least half of the times, to be weakly associated with any fall (adjusted RR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.04–1.33) relative to never having frequency [Citation10]. The association was slightly stronger for recurrent falls (adjusted RR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.02–1.53).

Another large prospective study, with extensive adjustment for potential confounders, by Frost et al. found frequency (definition not given) to be moderately associated with any fracture (adjusted HR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.25–3.36) [Citation13]. Although results were also given for osteoporotic fractures, it was not clear how they were defined.

Other LUTS

The other symptoms on the IPSS (incomplete emptying, intermittency, urgency, weak stream, and straining) were examined for association with any fall and recurrent falls in the well-conducted study by Parsons et al. [Citation10] The strongest associations were found between urgency and any fall (adjusted RR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.17–1.47) and recurrent falls (adjusted RR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.33–1.89), and between straining to void and any fall (adjusted RR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.06–1.46) and recurrent falls (adjusted RR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.27–2.02). The risks above were shown for men who had the symptoms at least half the time relative to those who never did. Other symptoms had weaker associations with falls.

This study by Parsons et al. also showed that high total IPSS (20–35 points) were associated with any fall (adjusted RR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.15–1.53) and recurrent falls (adjusted RR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.31–2.02) relative to men with low IPSS (0–7 points).

Discussion

In our study, we systematically reviewed the association of LUTS with falls, injuries and fractures in community-dwelling older men. Although studies varied in methodology, incontinence and storage symptoms such as urgency, nocturia, and frequency were consistently shown to be associated with falls. The associations were weak to moderate when restricted to six studies with low risk of bias due to confounding. These findings are in line with the past studies predominantly or exclusively of women [Citation2]. Fewer studies examined fracture as an outcome of which only one study showed an association between frequency and all fractures. No study looked at injuries as an outcome.

As might be expected, the extent to which potential confounders were adjusted for had a substantial influence on observed effect sizes in included studies. The strongest evidence for an association between LUTS and falls comes from the study by Parsons et al. [Citation10]: it had a large sample size, closely followed up participants for falls, assessed a wide range of LUTS using a validated questionnaire, and adjusted the risk estimates for an exhaustive list of fall risk factors that have previously been identified.

The time frame and frequency for the occurrence of LUTS was specified only in the study by Parsons et al. using the IPSS [Citation10]. It is preferable to ask about the occurrence of LUTS during a specific period of time because LUTS status is known to change dynamically over time: a 30% annual remission rate and a 10% annual incidence of incontinence was reported in community-dwelling older men [Citation17]. As the majority of male incontinence includes a component of urgency [Citation18], it is expected that there will be a change in storage symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia in keeping with the progression and remission of incontinence. Frequency of each symptom should also be asked because participants might regard symptoms that occur infrequently as insignificant. Although incontinence is not included in the IPSS, other validated questionnaires such as the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) may be utilized which incorporates the time frame and frequency of occurrence [Citation19]. The direction of bias that these ambiguities about time frame and frequency of symptoms may have introduced is uncertain. Administration of pad weight test or bladder diary may have provided better objective evidence of LUTS but may have been considered to be too resource intensive in large-scale studies. Thus we judged that the use of self-administered questionnaires which ensures privacy to be acceptable [Citation20].

A fall is defined by World Health Organization to be “an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level” [Citation21]. Most of the studies included in this review did not explicitly define falls. If falls were not well defined, this may have inflated the number of falls because older people may regard merely losing balance without landing on lower level as falling [Citation22]. The impact of inclusion of “near-falls” on the association with LUTS is uncertain. Only Parsons et al. prospectively determined the occurrence of falls. Although the other studies that relied on recall of the past year may not be ideal, Mackenzie et al. demonstrated that recalls of falls are fairly reliable in people aged 70 and older [Citation23]. As has been found in most studies on fall risk factors, stronger associations were consistently found with “recurrent falls” than “any fall” in the study by Parsons et al. [Citation10] Single falls may occur by chance to people with no tendency to fall whereas recurrent fallers may be more distinct as an at-risk group for falls.

Few studies examined fractures as an outcome. As discussed above, LUTS status changes dynamically over time. It, therefore, may not be appropriate to examine the association between LUTS at baseline and an outcome such as fractures in the following five years. Alternatively, it would require unfeasibly large sample size to observe sufficient number of fractures in a shorter period of time.

Our review showed that both urgency and incontinence were associated with falls in men. As the majority of incontinence in men is known to include an urgency component [Citation18], the question arises as to whether actual leakage of urine makes any additional contribution to fall risk beyond the sense of urgency alone. To answer this question, data need to be collected to differentiate between subjects with urgency without incontinence and those with urgency that results in incontinence.

High IPSS were associated with falls. Multiple symptoms within voiding or storage symptom subcategories tend to coexist in older men because the voiding symptoms may reflect different aspects of either bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) or impaired detrusor contractility, and storage symptoms reflect different aspects of overactive bladder (OAB). In addition, voiding and storage symptoms often coexist because some of OAB may be secondary to BOO, and OAB and impaired detrusor contractility may coexist in older people as detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility. Hence, the IPSS may have potential in assessing the overall fall risk related to LUTS. Although incontinence is not included in the IPSS, it is not yet certain whether it carries any additional risk of falls over the symptoms in the IPSS as discussed above.

There are a few limitations to our review. First, the results of this review may not directly apply to frailer and less mobile men in the community who may be at greater risk of falls. Some studies limited participation to healthier men in clearly defined inclusion criteria while the other studies that did not limit participation in any way are still likely to have undersampled these men. Second, it is uncertain whether medical, surgical, or behavioral interventions to LUTS alone may reduce falls in community-dwelling older people. A systematic review that investigated whether treating LUTS decreases falls identified two randomized controlled trials in nursing home residents: one that implemented a multidimensional intervention program including prompted toileting and physical exercise reported significant reduction in falls; and the other one that prescribed an anticholinergic agent failed to reduce falls [Citation24]. No study that reported the association between LUTS and falls in either men or women determined the events that precipitated the falls either. LUTS may directly precipitate falls or they may be merely a marker of other factors that cause falls: for example, hypogonadism has been shown to often coexist with LUTS and some of the characteristic symptoms of hypogonadism such as depressed mood, cognitive impairment and decreased muscle mass and strength are risk factors for falls [Citation25]. The circumstances of falls should be explored to generate hypothesis about what types of interventions should be incorporated in multidimensional fall prevention strategies. Also, future trials to treat LUTS should consider including falls as an endpoint.

Conclusion

Urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract storage symptoms were consistently shown to have weak to moderate association with falls in community-dwelling older men in studies with low risk of bias for confounding.

Evidence is lacking on whether medical, surgical, or behavioral interventions to LUTS decrease fall risk in community-dwelling men. The circumstances of falls in men with LUTS should be explored to improve fall prevention strategies.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declaration of interest.

References

- Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1701–7

- Chiarelli PE, Mackenzie LA, Osmotherly PG. Urinary incontinence is associated with an increase in falls: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother 2009;55:89–95

- Chapple CR, Wein AJ, Abrams P, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms revisited: a broader clinical perspective. Eur Urol 2008;54:563–9

- Stalenhoef PA, Crebolder HF, Knottenrus JA, Van Der Horst FG. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of falls among elderly subjects living in the community: a criteria-based analysis. Eur J Public Health 1997;7:328–34

- Egger M, Schneider M, Smith GD. Meta-analysis: spurious precision? Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 1998;316:140–4

- Stewart RB, Moore MT, May FE, et al. Nocturia: a risk factor for falls in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:1217–20

- Yasumura S, Haga H, Nagai H, Suzuki T. Rate of falls and the correlates among elderly people living in an urban community in Japan. Age Ageing 1994;23:323

- de Rekeneire N, V M, Peila R, et al. Is a fall just a fall: correlates of falling in healthy older persons. The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:841–6

- Asplund R. Hip fractures, nocturia, and nocturnal polyuria in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2006;43:319–26

- Parsons JK, Mougey J, Lambert L, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms increase the risk of falls in older men. BJU Int 2009;104:63–8

- Nakagawa H, Niu K, Hozawa A, et al. Impact of nocturia on bone fracture and mortality in older individuals: a Japanese longitudinal cohort study. J Urol 2010;184:1413–18

- Foley AL, Loharuka S, Barrett JA, et al. Association between the Geriatric Giants of urinary incontinence and falls in older people using data from the Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study. Age Ageing 2012;41:35–40

- Frost M, Abrahamsen B, Masud T, Brixen K. Risk factors for fracture in elderly men: a population-based prospective study. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:521–31

- Hedman AM, Fonad E, Sandmark H. Older people living at home: associations between falls and health complaints in men and women. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:2945–52

- Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol 1992;148:1549–57. discussion 64

- von Elm E, Egger M. The scandal of poor epidemiological research: reporting guidelines are needed for observational epidemiology. BMJ 2004;329:868–9

- Herzog AR, Diokno AC, Brown MB, et al. Two-year incidence, remission, and change patterns of urinary incontinence in noninstitutionalized older adults. J Gerontol 1990;45:M67–74

- Anger JT, Saigal CS, Stothers L, et al. The prevalence of urinary incontinence among community dwelling men: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. J Urol 2005;176:2103–8. discussion 8

- Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, et al. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2004;23:322–30

- Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:281–91

- World Health Organization. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. Available from: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf [last accessed 2 Nov 2015]

- Zecevic AA, Salmoni AW, Speechley M, Vandervoort AA. Defining a fall and reasons for falling: comparisons among the views of seniors, health care providers, and the research literature. Gerontologist 2006;46:367–76

- Mackenzie L, Byles J, D’Este C. Validation of self-reported fall events in intervention studies. Clin Rehabil 2006;20:331–9

- Batchelor FA, Dow B, Low MA. Do continence management strategies reduce falls? A systematic review. Australas J Ageing 2013;32:211–16

- Lunenfeld B, Mskhalaya G, Zitmann M, et al. Recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of hypogonadism in men. Aging Male 2015;18:5–15