Abstract

Prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been debated for many years, between an organ-specialist perspective versus a public health view. As an illustration, the Wonca Europe Council decided in 2004 to withdraw its support to the 2003 European Guidelines. This paper discusses the main sources of disagreement, most important the levels of risk when treatment should be offered. The Norwegian Guideline for primary prevention of CVD (2009) introduced a new principle of age-differentiated risk levels. Pharmacological treatment should be offered to all persons aged 40–49 years with 10-year mortality risk ≥ 1%, all persons aged 50–59 years at ≥ 5% risk, and all persons aged 60–69 years at ≥ 10% risk. Lower thresholds for younger persons are based on the fact that life years lost, will be considerable if drugs are prescribed only for risk levels above 5%. For persons aged 60–69 years, age is the dominant risk factor and the benefits of treatment are smaller. The implications of the recommendation are discussed, both at an individual and a societal level. Compared to the European 2007 guidelines, the total sum of life years gained is about the same, but the number of patients treated is considerably lower.

KEY-MESSAGE(S):

A population strategy is urgent, but controversial. Legislation and taxes should be used in most countries to combat the cardiovascular disease epidemic.

In individual primary prevention, support sustainable intervention thresholds for risk, giving priority to the younger and the persons with the highest risk.

Use total risk tools and avoid ‘single risk focus’.

Introduction

At risk—some or all?

Prevention of cardiovascular disease is an essential, everyday task for most general practitioners. The vision in this field of medicine is to avoid premature death and disability due to cardiovascular diseases in our societies, by treating people with risk factors for disease. However, most people dying of cardiovascular disease have low levels of risk—lower than the 5% 10-year death risk that is established as cut-off level in the European Joint Guidelines (2007) (Citation1). Data from Score, the epidemiological survey underlying these guidelines, showed that nearly half of all cardiovascular deaths occurred among people with less than 5% absolute risk. The proportion of the population with risk levels below 5% is much greater than the proportion with high risk. If we should lower the risk level for intervention in order to prevent death or disease among people with less than 5% risk, we would need to treat most of the adult population. This is not sustainable, and individual-oriented prevention must, therefore, be supplemented by other strategies to influence death rates in most of the cases.

Preventing future disease in healthy individuals

Prevention of disease in individuals without clinical signs of any illness, but with an increased risk for a particular disease is denoted primary prevention. To prevent new episodes of a clinically diagnosed disease is secondary prevention.

Primary and secondary prevention may be clinically very alike, as the patients largely will be offered the same treatment. However, there are some important differences:

In primary prevention, the person is healthy and has no evidence of disease. The person has an elevated risk for future disease, but he or she is not a patient. This fact raises a major ethical dilemma, which is often under-communicated: Treating healthy risk individuals means treating people with possibly life long medication, with a risk of imposing side effects and doing harm to a person who might live a long life without disease if left alone.

In secondary prevention, the person has evidence of disease and the absolute risk for a new event is usually higher. The person is a patient. The treatment we give is a treatment for an established disease. The role of the medical profession is clearer and the disagreements are not so strong.

Dilemmas and conflicts

This paper will focus on primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Historically, there are three major dilemmas or challenges, and subsequent conflicts in this field of medicine: (1) Do we need a population strategy— or only an individual-oriented professional-based strategy for prevention? (2) How should 'high risk’ be defined? More precisely: What should be the risk thresholds for interventions? (3) Which interventions should be used and what are the treatment goals?

Population versus individual-oriented strategy

As doctors, we tend to focus on treating the individual high-risk patient, forgetting the vital role of mass strategies. There is overwhelming evidence that cardiovascular diseases are multi-factorial and largely influenced by our modern way of life. According to the INTERHEART study (Citation2), a large international cross-sectional study, these nine modifiable risk factors accounted for 90% of the population attributable risk: smoking (current and former), ApoB/ApoA1 ratio, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, abdominal obesity, psychosocial factors, sufficient daily intake of vegetables and fruit (preventive effect), sufficient physical activity (preventive effect), moderate alcohol intake (preventive effect).

There are great differences between European countries in death rates caused by cardiovascular disease. The changes in death rates during the last 40 years in different regions are even more diverging. According to the WHO database, (Citation3) the standardized death rate caused by coronary heart disease for men up to 64 years in Greece has increased from 23 to 29 per 100 000 from 1970 to 2010. At the same time, the death rate in Poland increased to 65 per 100 000 the first 20 years and then decreased to the Greek level today. In Russia, there has been an increase from 93 to 140 per 100 000 over the last 20 years—really a population catastrophe, whereas the best guy in class—Russia's neighbour Finland, has achieved an 80% decrease in death rate—from 117 to 22 per 100 000 during these 40 years.

These differences are interesting and need to be analysed extensively. For any politician engaged in disease prevention and health promotion, it must be important to look to countries that have succeeded in reducing the epidemic of cardiovascular disease, like Finland and other Nordic countries. In these countries, campaigns for reducing the most important risk factors like smoking and unhealthy food, and promoting more physical exercise have—to a large extent—been successful. For example, the prevalence of daily smoking among men aged 40–42 in Tromsø County, Norway, fell from 60% in 1974 to 34% in 2001, and is now close to 20%. (Citation4) At the same time, the mean cholesterol levels have fallen from 7.1 to 5.9. It is worth noting that most of the reduction occurred before the statin era. It is not the result of medication.

All taken together, there is good evidence that the changes in risk factor levels in the general population accounts for more than 2/3 of the decrease in death rates of cardiovascular disease in the Northern countries. The most important factor is probably the decrease in smoking, but lowering of cholesterol due to changes in diet in the population is also important. The most powerful tools in this respect are not public campaigns, but price and legislation (Citation5). To implement such measures we need brave and dedicated politicians, and voters to support them. For the medical profession, it is extremely important to tell the politicians that legislation, prizing and other mass strategies are much more important and effective tools for prevention than individual-oriented strategies ever can be. Sustainable prevention means that the exposure of the population to risk factors is reduced. This is achieved through mass strategies, not by prescription of drugs.

Challenges in individual-oriented prevention: Risk thresholds

Cardiologists versus GPs

In individual-oriented prevention, the most important question has been what risk level is appropriate for intervention, such as suggesting medication. This question is normative and raises ethical and political problems, and should be answered by processes involving politicians and lay people. Until now, it has been left to the medical profession, and most of the disagreement has been between primary care and secondary care specialists, often between general practitioners and cardiologists. Based on many randomized controlled trials, cardiologists may argue that treating people with a drug can reduce relative risk for events by e.g. 30% (‘Treatment saves lives! Treat as many as possible!’). Alternatively, general practitioners may argue that the absolute risk level is essential. Thirty per cent reduction of a low absolute risk is not necessarily a big achievement, as intervention on low risk levels implies large numbers needed to treat. Furthermore, prescribing pills may cause side effects and take away the focus on changing life habits. Many GPs argue that medical diagnoses and treatment cause medical labelling and may lead to distress among healthy people, and reduce their ability to cope with their own lives. In addition, individual treatment of large proportions of the population is waste of resources, both in terms of work force in the health system and in terms of medication costs. There are many reasons to avoid large-scale medicalization of the society.

The major role of age in risk algorithms

Available risk algorithms today usually apply the absolute 10-year risk for cardiovascular death or disease. However, these risk tools are retrospective and tell us history. In countries with falling incidence of cardiovascular disease, they will over-estimate the risk.

Since total risk is heavily influenced by age and gender, the risk tables give priority to elderly men with moderate levels of blood pressure and cholesterol. If the threshold levels for treatment are low, large proportions of the elderly population will be targets for individual-oriented prevention and prophylactic medication. However, applying a fixed cut-off level of 5% absolute risk (as is done in the European guidelines) does not address elevated risk in younger persons.

Different strategies have been introduced to overcome these shortcomings of risk algorithms. In the European 2003 guidelines, risk for people up to 60 years was addressed by transposing the risk to 60 years of age—that is: a 40-year-old person with elevated risk factors should be treated as if he was 60 years of age (Citation6). Applying the 2003 guidelines on a Norwegian population would cause a major inflation of risk and risk factor treatment, as Linn Getz and others showed in a paper in 2005 (Citation7).

Before that, similar concerns had been expressed by general practitioners in many other European countries (Citation8), addressing the problems with aggressive treatment goals. This led Wonca Europe to withdraw its support to the 2003 European Guidelines. With the publication of the 2007 Guidelines, the principle of transposing risk to 60 years was abandoned, and a relative risk algorithm was introduced to guide the clinician when dealing with younger persons with elevated risk. (Citation1) We do not know, however, how this relative risk chart is used in practice, and the guidelines do not contain a precise advice on how to use it. The problem is better understood when we take an example:

Peter is a smoking 44 year old man in Norway, a high-risk region of Europe according to SCORE. He has a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg and cholesterol 6.1 mmol/l. According to SCORE, he will have an absolute 10-year death risk of 2%—substantially lower than the cut off level of 5%. Adding the information of relative risk reveals that his relative risk is six times that of a non-smoker with BP < 140 mmHg and cholesterol < 4. Quitting smoking will reduce his risk, so that would be a relevant starting point. However, if he continues to smoke—would you suggest medication? Maybe—but the guidelines do not help you with a clear answer. His absolute risk is 2%, but he obviously will be in danger of losing many years in the future, beyond the 10 years perspective the SCORE algorithm offers.

Developing the Norwegian guideline

The Norwegian Health Directorate was concerned about the disagreements between general practitioners and organ specialists, and invited key stakeholders to engage in a process to develop new national guidelines targeting both general practitioners and other specialists involved in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The guidelines were published in 2009 (Citation4), and an article describing the process and the recommendations has recently been published (Citation9). The advisory group was multi-disciplinary, and consisted of specialists from general practice, cardiology and other relevant specialties, and patient organizations. All stakeholders were asked to explain their arguments, and also to acknowledge the existence of a diversity of reasons based on the scientific evidence, the evidence on cost-effectiveness, and health policy and ethical concerns.

The guideline development was open and transparent, and was divided into three parts: (a) An independent systematic review and meta-analysis of all relevant studies, which was performed by Norwegian Knowledge Centre for Health Services [10]; (b) A systematic review of relevant cost-effectiveness studies (Citation11); and (c) Development of evidence based recommendations according to the GRADE method (Citation12).

To overcome the 'age problem’, it was decided to apply an age-adjusted threshold for risk. Pharmacological treatment should be offered to all persons aged 40–49 years with 10-year mortality risk ≥ 1%, all persons aged 50–59 years at ≥ 5% risk, and all persons aged 60–69 years at ≥ 10% risk. For single risk factors, systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mmHg or cholesterol ≥ 8 mmol/l were considered cut-off levels for treatment. It was also decided to build the risk algorithm on a national survey, since the SCORE algorithm (high-risk algorithm) over-estimated the risk for Norwegian patients.

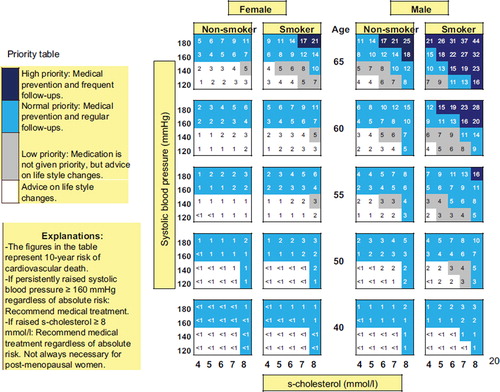

The result was the NORRISK instrument, supplied with a priority table, which is meant to help the physicians to give the right priority to the persons with the highest risk () (Citation13). Here, persons in the dark blue areas on the figure shall have high priority, be offered pharmacological treatment and tight follow up. The light blue area means normal priority; pharmacological treatment and ordinary follow up. The grey area represents low priority, usually medication is not recommended but rather advice on life habits. The white area represents those who should not get individual-oriented interventions.

Benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses

The cost-effectiveness model revealed that in men aged 40–49 years with 1% risk treatment with a statin and two anti-hypertensives gave a benefit of 2.9 life years, while the gain for men aged 60–69 years with 5% risk was 1.7 years. The procedure of age-differentiated risk thresholds leads to a shift from absolute 10-year risk assessment only to consideration of expected benefit in terms of life years gained, and the distribution of these benefits in different age groups.

To answer the concerns about medicalization and priority settings, a group of epidemiologists performed a model analysis of the consequences of applying these cut-off levels in the Norwegian population of 4.9 million inhabitants, based on the Tromsø survey. The results of using age-differentiated approach were compared with the 5% undifferentiated risk threshold used in the European Guidelines. An undifferentiated 5% risk threshold gives a life years gain of 539 000, while the differentiated risk approach gives 531 000, a difference of 8000 life years in the benefit of 5% risk for all. However, the number of persons treated would be 247 100 with 5% risk approach, and 198 100 with differentiated risk, a reduction in patients by nearly 50 000 in benefit of the age differentiated risk approach. This approach will benefit the young men (40–49 years) with 86 000 years, while the 60+ men will lose 22 000 years and the 60+ women will lose 72 000 years ().

To sum up the arguments for age differentiated risk thresholds, with lower risk levels for the younger and higher threshold for the elderly: Use of a fixed intervention threshold for risk without adjustment for age, as in the European Guidelines, does not capture total lifetime perspective. Differentiated risk thresholds leads to higher life expectancy for the younger (men aged 40–49 years) and lower life expectancy for the elderly (men aged 60–69 years). The result is more equal distribution of expected life years during the lifetime. The procedure will also prevent large-scale medicalization of the elderly population, as the number needed to treat is considerably lower than the 5% risk for all procedure.

Practical use of the risk assessment tools and the guidelines

Estimating risk

Common for both the Norwegian and the European Guidelines, and for most current international guidelines, is the multiple risk assessment approach, and the use of tools for estimating the absolute 10-year risk of cardiovascular death for the individual. For the clinician, there are important limitations to these tools, which should be taken into account.

Most of them give the death risk only, not the risk for events (disease). A ‘rule of the thumb’ is to multiply the death risk with three for the younger and with two for the elderly to obtain the risk for disease (Citation14). In addition, other risk factors should be taken into account: (a) Diabetes: multiply risk by 1.5, or more if severe; (b) Family history: for first-degree relative (male relative with cardiovascular disease ≤ 55 years, female ≤ 65 years) multiply risk by 1.5; (c) Dyslipidaemia: Low HDL or high triglycerides increases risk (factors not established); (d) Abdominal fat increases risk; (e) Social or psychological stress increases risk.

To help doctors to use the risk instruments, it is necessary to deliver easy-to-use computer-based tools (Citation15). At this web site (http://rkalk.helsedir.no/default.aspx), doctors and patients will find an electronic risk calculator with priority settings and suggestions for interventions.

Treatment options

When the risk level is established, interventions should be discussed with the patient. All persons with increased risk (over the intervention thresholds) should be offered advice on life style habits, both before and during initiation of pharmacological treatment. These include interventions to quit smoking, an adequate diet, and concrete advice on physical activity. These recommendations are largely identical to the European guidelines. Regarding medication, the general advices are listed below:

Statins are effective in primary prevention (recommendation strong, evidence high).

The following groups of anti-hypertensives are effective in primary prevention: Thiazides, calcium channel blockers (CCB), ACE-inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), ß-blockers (BB) (recommendation strong, evidence high).

According to the cost-effectiveness analysis, calcium channel blockers, thiazides and ACE-inhibitors have the lowest cost-effectiveness ratio. They are, therefore, recommended first-line drugs. Losartan and valsartan (ARB) have just gone off patent in Norway and are now also included.

ß-blockers and α-blockers are not considered first-line drugs, but may be used on indication or in combination therapy (recommendation weak, evidence medium).

Combination therapy with two or more drugs is often necessary for moderate/high blood pressure and high absolute risk (recommendation strong, evidence high).

The guidelines also list indications and contra-indications.

Anti-coagulation: There is evidence that acetylsalicylate 75 mg once daily is effective in primary prevention for persons with high and very high absolute risk. For women there is only evidence for age > 65 years (recommendation weak, evidence medium).

Key-messages

A population strategy is urgent, but controversial. Legislation and taxes should be used in most countries to combat the cardiovascular disease epidemic.

In individual primary prevention, support sustainable intervention thresholds for risk, giving priority to the younger and the persons with the highest risk.

Use total risk tools and avoid ‘single risk focus’. It is better to treat high-risk individuals than to measure blood pressure in all.

The preventive effects of statins and most anti-hypertensives are well documented.

The higher the risk, the more interventions. Combination therapy with lower doses is usually better than single therapy in high dose.

Being a general practitioner, I should like to end with the personal recommendation to follow your patient, to be aware of side effects of medication and to focus on lifestyle habits rather than blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Learn to know your ‘risky patient’. He or she is unique, and life usually is complicated. To change life habits is difficult for most of us, and the support from the personal doctor is essential.

Acknowledgments

The author should like to thank Professor Jørund Straand, University of Oslo, for valuable comments during the revision of the manuscript.

Financial sources

The Norwegian expert group and the publication of the Norwegian Guidelines were financed by the Norwegian Health Directorate. My participation in the European expert group was financed by Wonca Europe.

Declaration of interests: The author was a member of the European Joint Task Force IV (Prevention of cardiovascular disease in Europe) 2005–2008, appointed by Wonca. The author also was a member of the expert group of the Norwegian National Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease 2004–2009. The author has no financial interests in the field of medicine covered in the article.

References

- Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, . European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Full text. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(Suppl 2):S1–113.

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, . Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004;364:937–52.

- WHO Europe Health for all database. Available at: http://data.euro.who.int/hfadb/ (accessed 25 August 2011).

- Norheim OF, Gjelsvik B, Kjeldsen SE, Klemsdal TO, Madsen S, Meland E, . National guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. 10 May 2009. Oslo, Directorate of Health, Oslo, Norway. Available at: http://www.helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/nasjonale_faglige_retningslinjer/nasjonale_retningslinjer_for_individuell_prim_rforebygging_av_hjerte__og_karsykdommer_399154 (accessed 4 December 2011).

- Joossens L, Raw M. The tobacco control scale: A new scale to measure country activity. Tob Control 2006;15:247–53.

- De BG, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, Brotons C, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, . European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Third joint task force of European and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of eight societies and by invited experts). Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003;10:S1–S10.

- Getz L, Sigurdsson JA, Hetlevik I, Kirkengen AL, Romundstad S, Holmen J. Estimating the high risk group for cardiovascular disease in the Norwegian HUNT 2 population according to the 2003 European guidelines: Modelling study. Br Med J. 2005; 331:551.

- Editorial. A pressure to agree. Lancet 1999;354:787.

- Norheim OF, Gjelsvik B, Klemsdal TO, Madsen S, Meland E, Narvesen S, . Norway's new principles for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Age differentiated risk thresholds. Br Med J. 2011;343:d3626.

- Håheim LL, Fretheim A, Brørs O, Kjeldsen SE, Kristiansen IS, Madsen S, . Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, with emphasis on pharmacological interventions. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Center for Health Services; 18 December 2008. Report No.: 20-2008. Available at: http://www.kunnskapssenteret.no/Publikasjoner/ (accessed: 4 December 2011).

- Wisloff T, Norheim OF, Selmer R, Halvorsen S, Kristiansen IS. Health economic evaluation of primary prevention strategies against cardiovascular disease. Oslo: Norwegian knowledge center for the health services; 18 December 2008. Report No.: 34-2008. Available at: http://www.kunnskapssenteret.no/Publikasjoner/ (accessed 4 December 2011).

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. What is ‘quality of evidence’ and why is it important to clinicians? Br Med J. 2008;3;336:995–8.

- Selmer R, Lindman AS, Tverdal A, Pedersen JI, Njolstad I, Veierod MB. Model for estimation of cardiovascular risk in Norway. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2008;128:286–90.

- Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De BG, Graham I, Taskinen MR, Wiklund O, . ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: The task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818.

- NORRISK Risk calculator. 1 September 2011. Oslo, Norwegian Health Directorate. Ref Type. Available at: http://rkalk.helsedir.no/default.aspx (accessed: 4 December 2011).